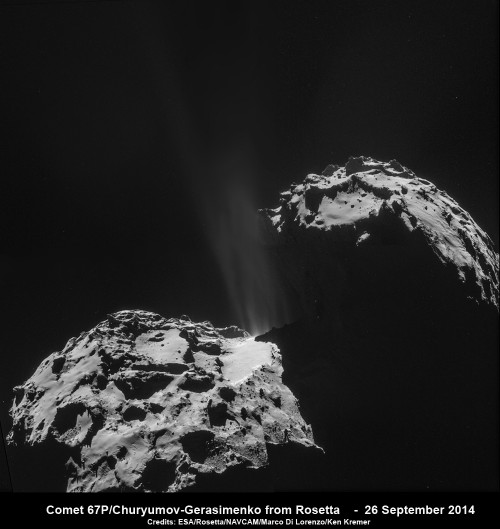

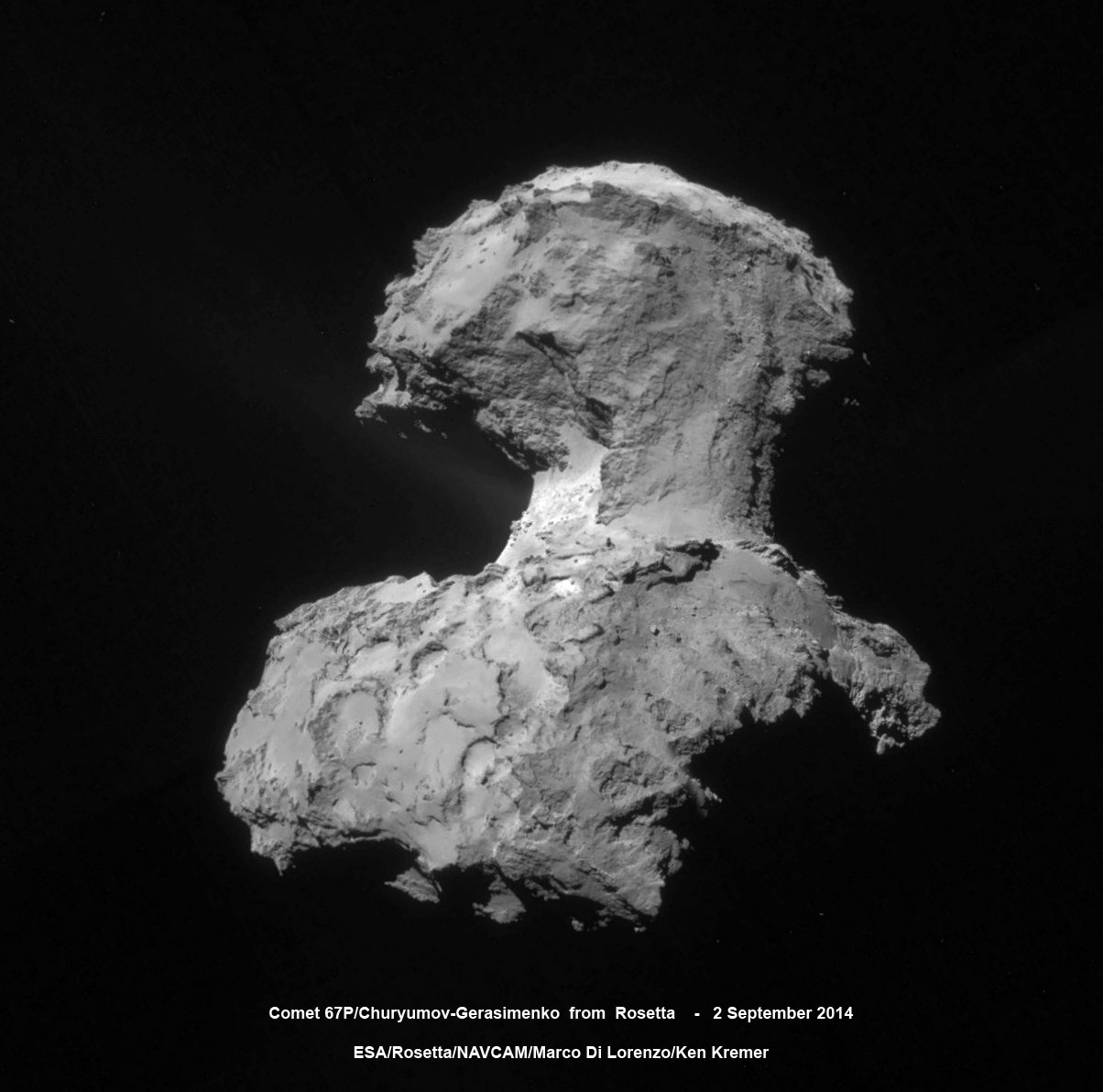

A spectacle of erupting jets are blasting away from the clearly active neck of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in stunning new imagery captured by Europe’s Rosetta spacecraft as it swoops in ever closer to this bizarre remnant from the formation of our Solar System.

The latest exquisite image quartet was shot Sept. 26 by the navigation (navcam) camera aboard the European Space Agency’s (ESAs) Rosetta orbiter at a distance of 26.3 kilometers (16 miles) from the center of the comet.

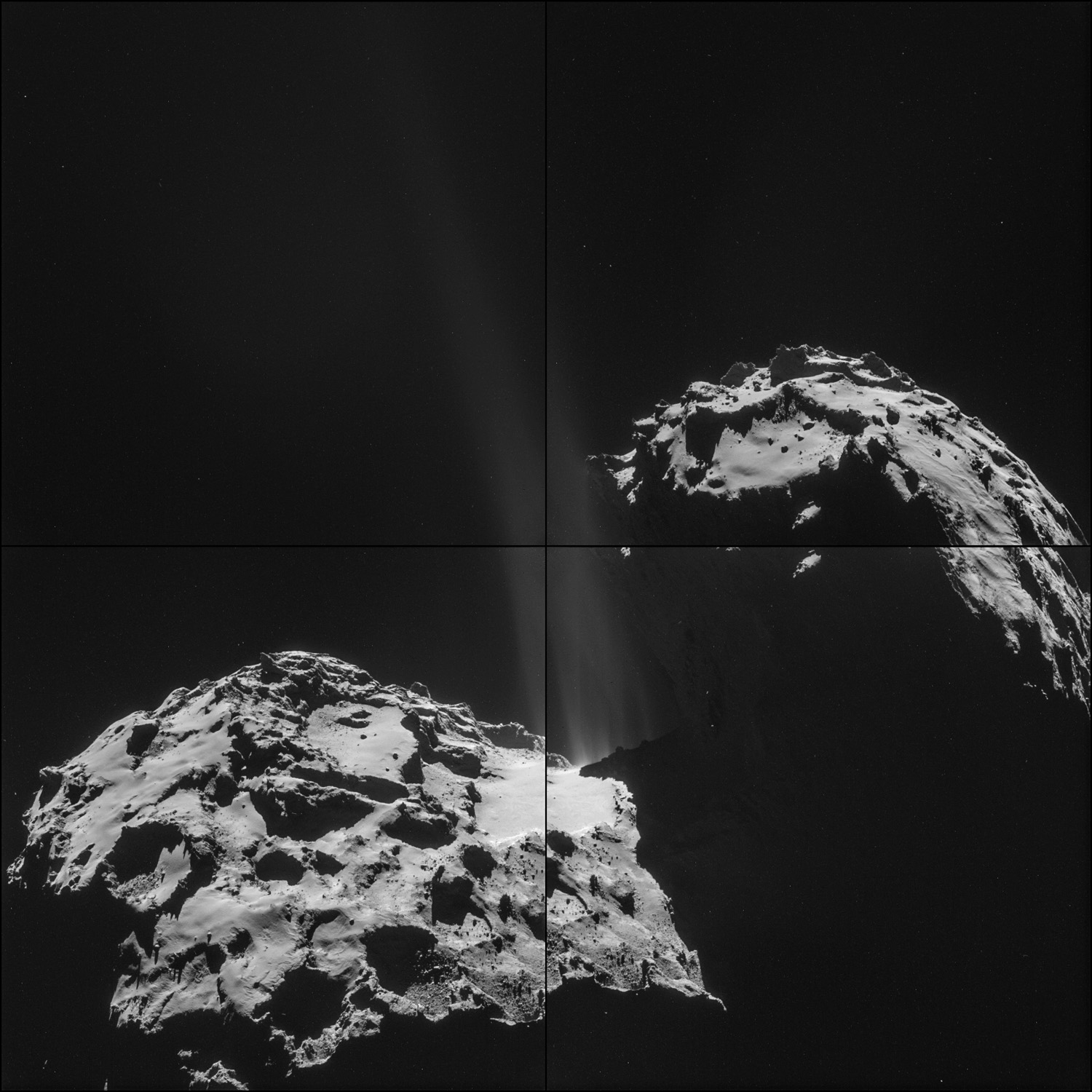

See our four-image photo mosaic, showing the images assembled together, above. For comparison, ESA’s montage of the four individual 1024 x 1024 pixel navcam images is shown below.

Navcam snaps the images as 2 x 2 rasters.

Jets of dust particles and sublimating ice are visibly exploding out from the comet’s “neck” region, centered between the two mysterious lobes of comet 67P, dubbed the “head” and the “body.”

The jets originate from several discrete areas of ice and gas escaping from inside the comet, hurtling out as a steam of dust particles. The coma now extends over 19,000 kilometers out from the nucleus into space, according to recent ground-based images taken to support Rosetta’s mission planning and observations.

Earlier measurements from the probes science instruments revealed that the ice is located mostly beneath the comet’s exterior, rather than from surface deposits.

Prior to publicly releasing the individual Sept. 26 navcam images, the Rosetta team did some internal processing, according to this ESA description:

“The individual images have been background subtracted to remove some striping and fixed noise patterns. In making the montage, the background levels have then been adjusted in order to make the images more or less equivalent, the vignetting in the corners of the images has been reduced, and some processing of the overall brightness and contrast has been applied using Adobe Lightroom. Finally, the montage has been rotated by 180°.”

As Rosetta orbits nearer the comet, its orientation with respect to the navcam camera changes significantly even over short time spans, thus causing increased distortion and thus greater difficulty in satisfactorily assembling the images into a pleasing mosaic.

In this case, the comet rotated 10 degrees over the 20 minute period between the first and last images while the spacecraft moved about 1 to 2 kilometers, according to an ESA statement.

Indeed the ESA team declined to create a mosaic from the Sept. 26 images, stating: “We have not made a proper mosaic on this occasion, because it is becoming extremely difficult at these close distances. It’s not easy to bring these images into alignment and thus we leave the challenge of making a reasonable mosaic from them to you!”

Of course, the image processing team of Marco Di Lorenzo and Ken Kremer—and others—accepted ESA’s bold challenge (and you can judge the results herein).

ESA’s Rosetta mission is comprised of an orbiter and a lander and marks mankind’s first attempts to orbit and touch down on the surface of a comet.

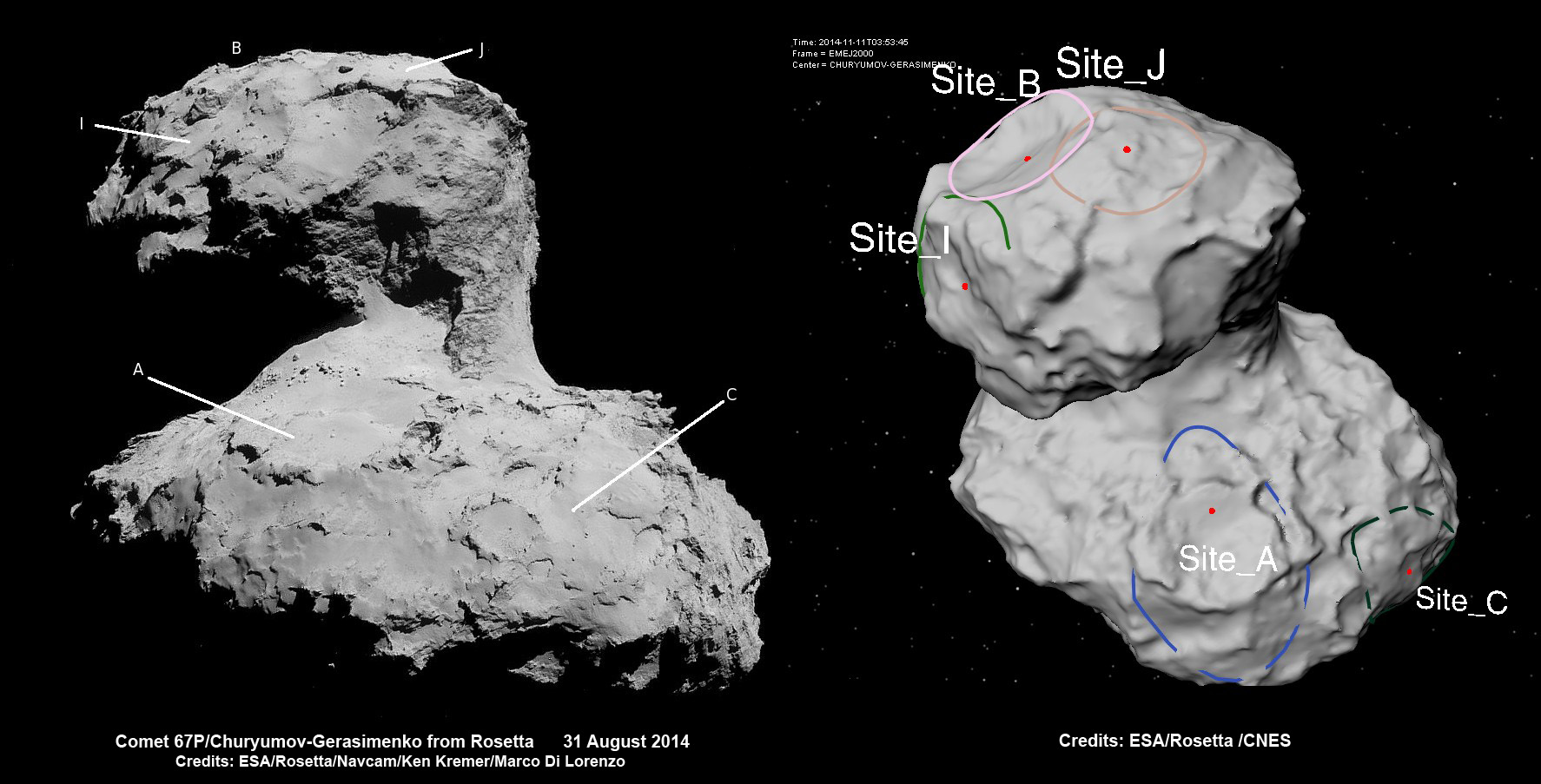

Since rendezvousing with the comet on Aug. 6, 2014, after a decade-long chase of over 6.4 billion kilometers (4 billion miles), a top priority task for the science and engineering team leading Rosetta has been “Finding a landing strip” for the piggybacked Philae comet lander.

The team’s primary task has been utilizing Rosetta’s 11 science instruments to conduct an unprecedented scientific analysis of the comet to gather as much data as possible to maximize the chances of success for the Philae lander to safely soft land on comet 67P and study it for as long as possible.

The imagery is critical to finding and characterizing a touchdown zone that’s both technically safe and scientifically interesting.

So the team has been in a race against time to first select a suitable landing zone quickly and then develop the complex landing sequences, since the comet warms up and the surface becomes ever more active as it swings in closer to the Sun and makes the landing ever more hazardous beyond November.

By late September the team announced that Nov. 12 was chosen as the date to deploy the Philae lander on its historic quest.

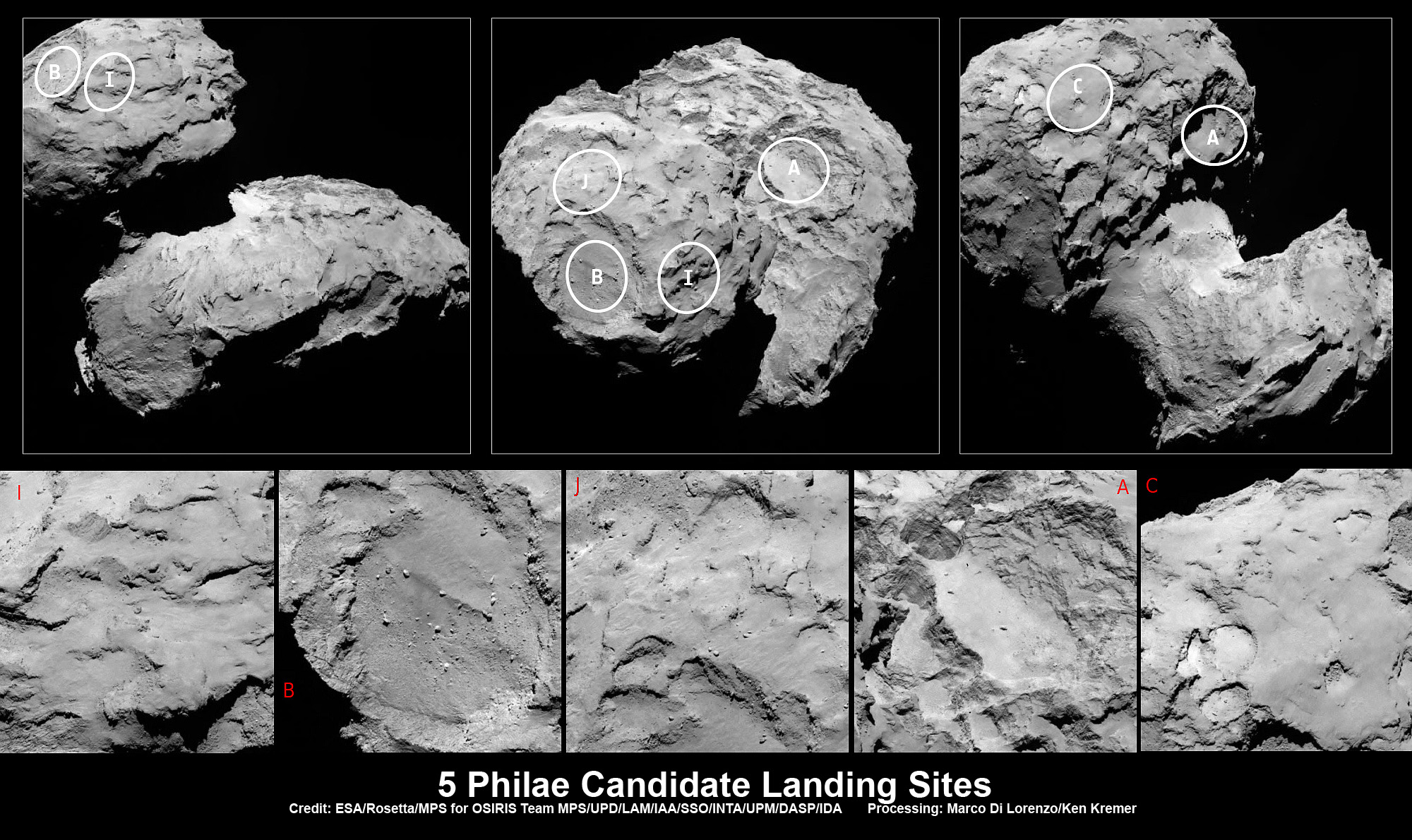

The “head” of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko had previously been selected as Philae’s primary landing site at a target known as “Site J,” which is located on the smaller of the two “lobes.”

The backup landing target, known as “Site C,” is located on the comet’s “body,” which is the larger of the two lobes. See both locations on the imagery herein.

Philae’s landing will be entirely automatic. The 100-kg lander is equipped with 10 science instruments.

The three-legged lander will fire two harpoons and use ice screws to anchor itself to the 4-kilometer-wide (2.5 mile) comet’s surface. Philae will collect stereo and panoramic images and also drill 20 to 30 centimeters into the comet to sample its incredibly varied surface.

Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer – kenkremer.com

The Rosetta orbiter will continue studying the comet’s evolution until late 2015—if all goes well—as it escorts the comet and then arcs away on its outbound voyage past the Sun toward Jupiter.

Stay tuned here for continuing developments.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Simply amazing photos! Since the Mariner 4 fly-by of Mars in 1965, planetary exploration has taken tremendous strides in our understanding of the solar system. Let’s hope that this mission is yet another example that will kindle the interest and imagination of a new generation of scientists, engineers and space enthusiasts.

Excellent article, Ken!

Fantastic photos! Great Article! Will the Philae Landing craft collect samples and return to Earth? So couldn’t we use all that venting Water Ice to make fuel and purify to drink???

Tracy – not a sample-return mission (unfortunately). But that will eventually happen as with Mars and the moon’s of Jupiter and Saturn. Will be exciting to see that!