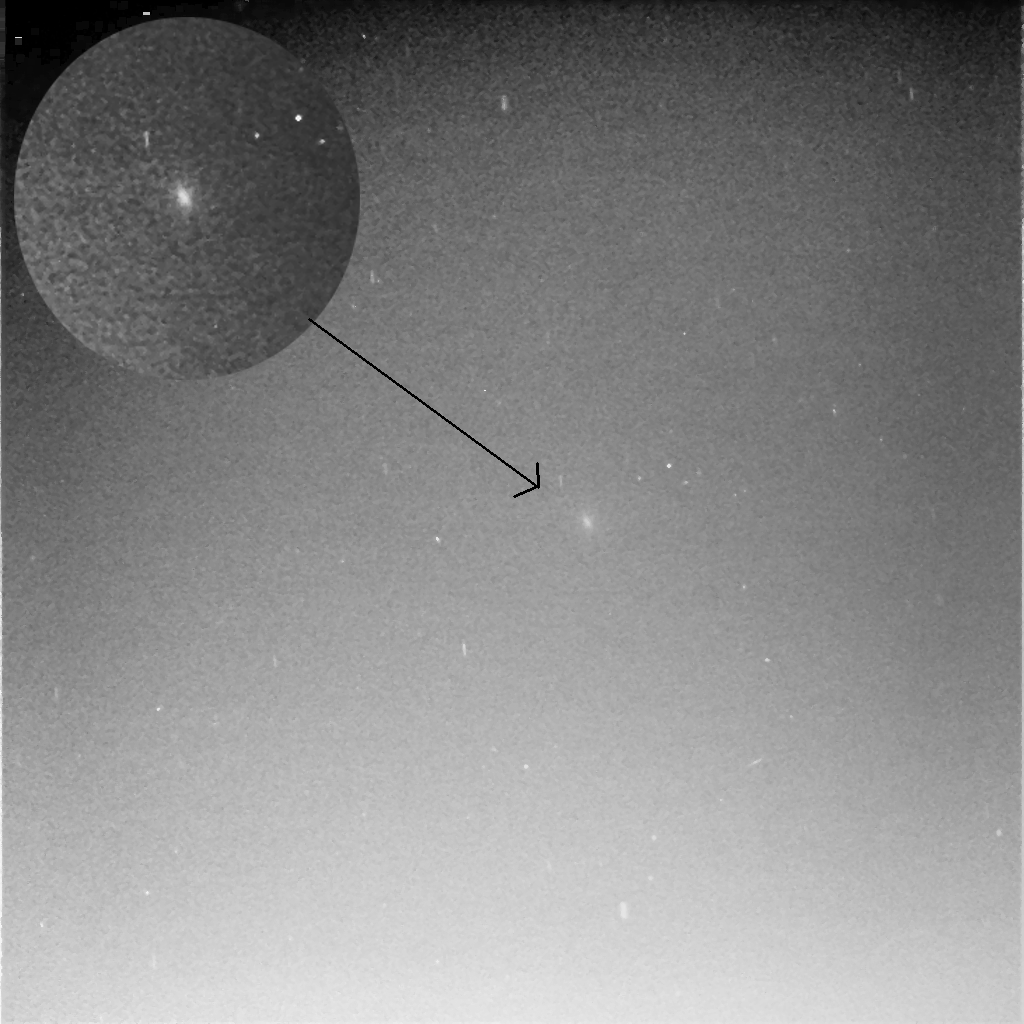

NASA’s Opportunity rover snapped the first-ever image of a comet from the surface of Mars during a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity as Comet Siding Spring (Comet C/2013 A1) made the closest known flyby of either Earth or Mars in recorded history—missing the Red Planet by a mere 87,000 miles (139,500 kilometers).

Opportunity captured the spectacular and history-making view of the “fuzzy” Oort Cloud comet by pointing her camera high up in the pre-dawn Martian sky on Sunday, Oct. 19, said “quite excited” Opportunity science team member Mark Lemmon of Texas A&M University, exclusively to AmericaSpace today (Oct. 20). See rover photo above with our enhanced view revealing more comet detail.

“Yes, the fuzzy object is the comet,” Mark Lemmon told AmericaSpace. Lemmon coordinated the carefully choreographed long-exposure observations taken by Opportunity’s high-resolution Pancam science camera.

“There are many beautiful views of the comet, but I’m quite excited to see the rover’s view, since it is pretty much what we could see!”

The comet trails in the fabulous night sky view are due to the nearly minute-long exposure time.

The first images were taken about 2.5 hours before the closest approach of the nucleus of comet Siding Spring to Mars during the pre-dawn hours. By the actual time of the comet’s closest approach the skies were lit by dawn’s twilight.

“It trails partly due to Mars’ rotation in the 50 second exposure, and partly due to the comet’s motion across the sky,” Lemmon stated.

“The observation started around 03:00 HLST (local solar time). Many more images were taken over 30-40 minutes, although the twilight will interfere with the later ones.”

Siding Spring swept nearest to Mars at around 2:27 p.m. EDT (18:27 GMT) on Oct. 19, zooming at over 126,000 mph and spewing massive clouds of dust.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell Univ./ASU/TAMU

And there are also some Martian dust storms swirling about.

“There’s a lot of high altitude dust right now, being kicked up by some distant, regional dust storms.”

The night sky view is from the rover’s current location, climbing up the rim of huge Endeavour Crater and looking above and across the crater’s vast expanse. See our photo mosaic from Endeavour crater.

“We looked in a fixed direction (no energy to move) around 50 degrees up and just north of east, in [the constellation] Cetus–seems about right with respect to the pan.”

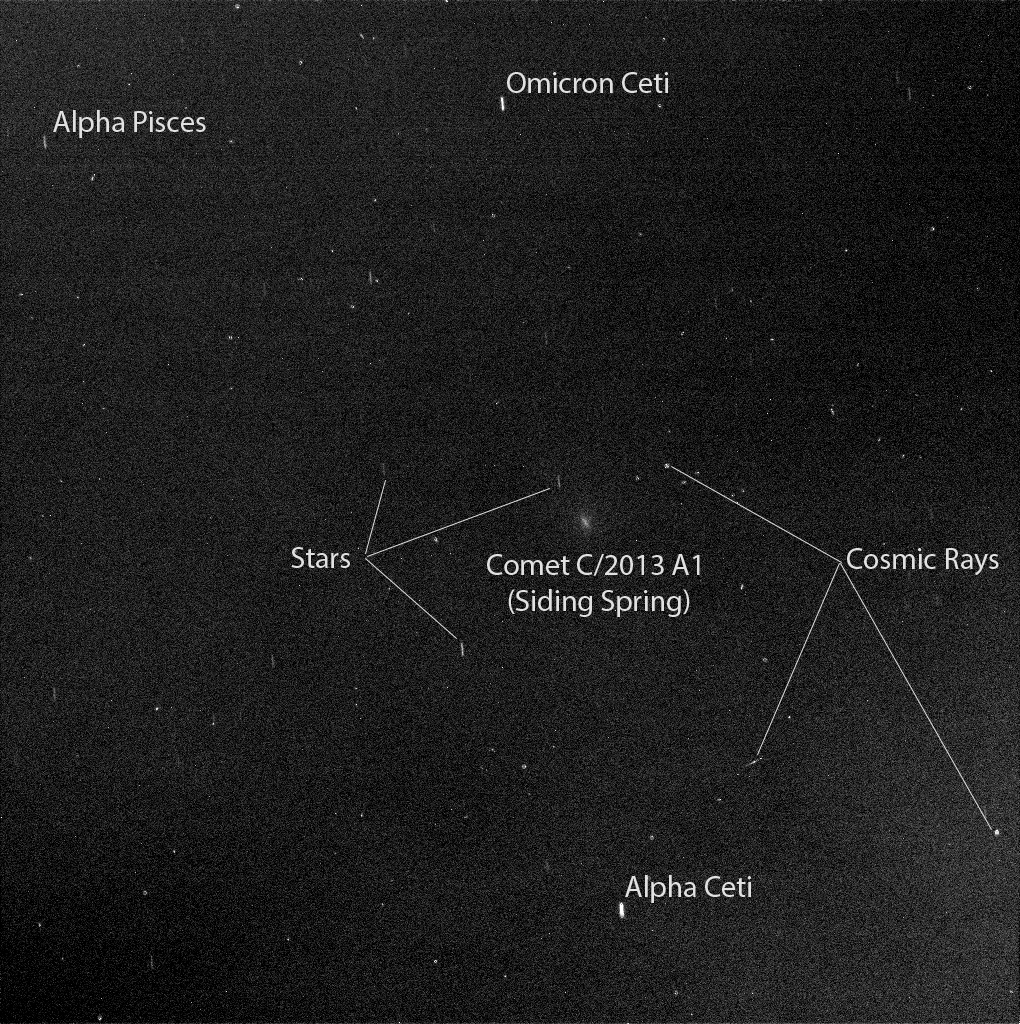

See NASA’s star map herein showing the comet’s location.

Siding Spring is an Oort Cloud comet making its first-ever passage through the inner Solar System during its millions-year-long orbital trek from the distant fringes of our Sun’s realm.

The Oort Cloud is a giant swarm of icy objects some 50,000 AU from the Sun and is believed to be material left over from the formation of the Solar System. No spacecraft has ever visited one before.

Since comet Siding Spring has never flown past the Sun before, the Mars encounter provides researchers with an unparalleled opportunity to learn vastly more about the nature and composition of its pristine materials, including water and carbon compounds, that existed during the formation of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago and have not been blown off by heating effects from a prior passage.

So the researchers were abuzz with excitement, and Lemmon waited and watched for Opportunity’s images to steam back to Earth in the middle of the night.

“It’s been a while since I was up at 2 AM waiting for rover data, but this was worth it!” said Lemmon.

The Siding Spring cometary encounter comes at an exceeding fortuitous time, coincidentally coinciding with the presence of a record-breaking armada of Martian science probes from the nations of Earth.

“On October 19, we’re going to observe an event that happens maybe once every million years,” Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary science division at NASA Headquarters, Washington, said during a NASA media briefing on Oct. 9.

“This is where a comet coming from the farthest reaches of the sun’s gravity will come to the inner part of our solar system. This comet will fly right in front of the planet Mars. Mars will be blanketed in cometary material.”

As the comet hurtled past Mars on Oct. 19 at about 35 miles (56 kilometers) per second, an international fleet of seven spacecraft, including five NASA orbiters and rovers and two additional orbiters from Europe and India, gathered unprecedented up close scientific observations of the comet and its huge coma and tail before and after Sunday’s closest approach, while simultaneously studying its effect on the tenuous Martian atmosphere.

All seven spacecraft survived the cometary close shave intact and are healthy, according to NASA, ESA, and ISRO.

There are no further comet images planned by Opportunity. However, additional images and spectral observations are expected soon from NASA’s Curiosity rover and the five orbiters.

“Opportunity will take no more Comet Siding Spring images, but will downlink what she has,” Lemmon elaborated.

“Curiosity has some images and spectra, most of which has not come down. Curiosity will take a final set of Comet Siding Spring images tonight [Oct 20], around 5:40 CDT, but they will not be relayed for at least many hours.”

The long-lived and world-renowned robot has been traversing across Mars for more than a decade and just notched another memorable first in her seemingly endless belt of groundbreaking scientific accomplishments with this first comet image from the surface of another planet.

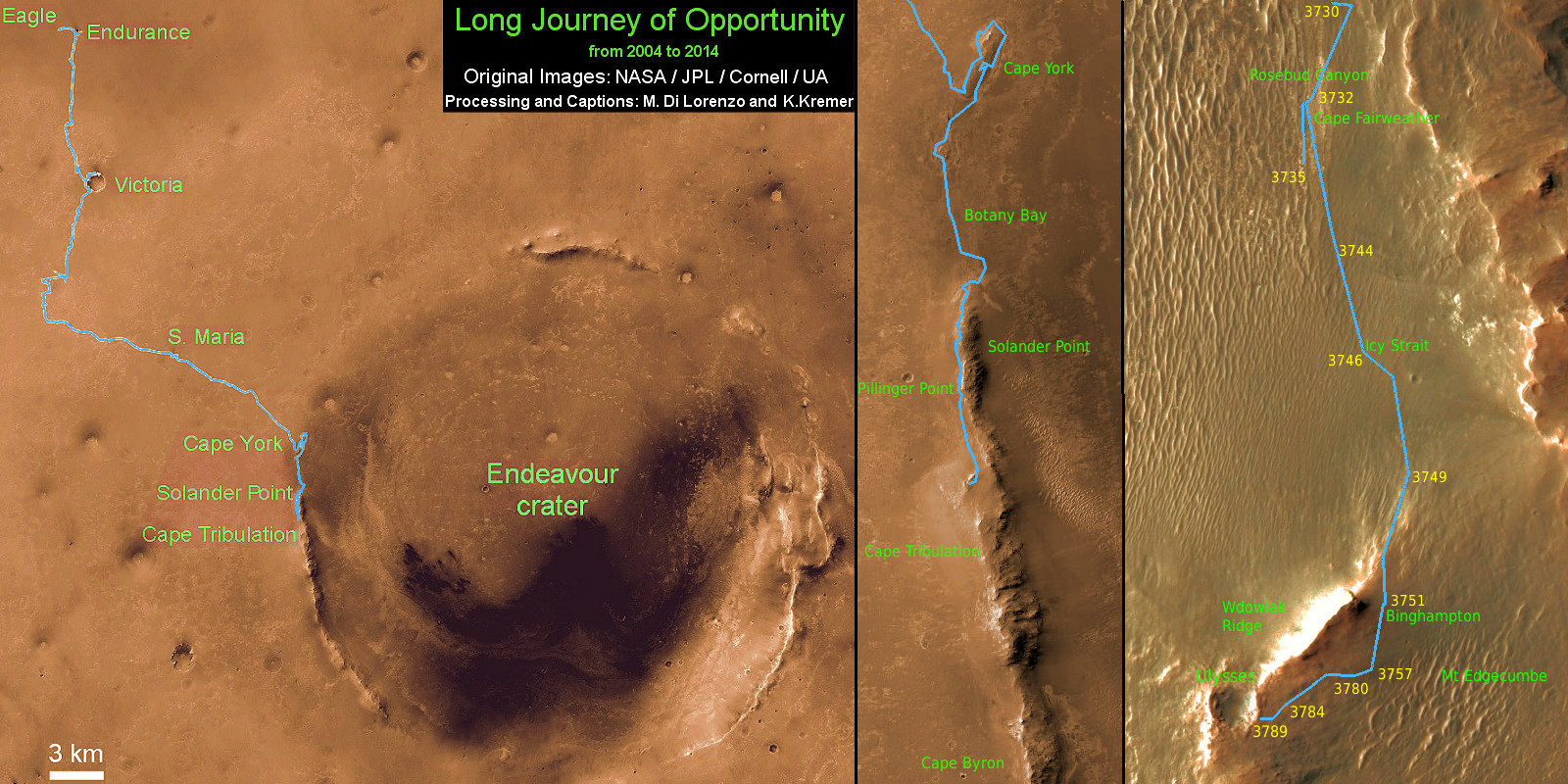

Today, Oct. 20, marks Opportunity’s 3818th Sol, or Martian Day, roving Mars. So far she has snapped over 197,400 amazing images since her air-bag assisted touchdown on Jan. 24, 2004, inside Eagle crater.

Opportunity’s total odometry is 25.34 miles (40.78 kilometers).

Stay tuned here for continuing developments about the comet encounter and much more.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

This map shows the entire path the rover has driven during a decade on Mars and over 3800 Sols, or Martian days, since landing inside Eagle Crater on Jan 24, 2004 to current location at Ulysses Crater at the western rim of Endeavour Crater and heading to clay minerals at Cape Tribulation. Opportunity discovered clay minerals at Esperance on Cape York– indicative of a habitable zone. Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell/ASU/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer – kenkremer.com

Incredible! For the first time in human history, we have observed a comet from the surface of another planet. This feat serves as a reminder that we have such tremendous technological capabilites that must not be lost on future generations.