The first 50 years of planetary exploration have seen the successful completion of humanity’s epic, first preliminary reconnaissance of almost the entire Solar System, from the scorching-hot innermost planet Mercury to the frigid ice giant Neptune in the doorstep of the vast, uncharted Kuiper Belt. During that time, various robotic spacecraft have also studied the fascinating terrestrial worlds of the inner Solar System in great detail, allowing scientists to construct very high-definition global color maps of their surfaces which have helped to reveal the unique, stark beauty of their never-before-seen planetary vistas. Yet, equally as fascinating, the large icy moons of the outer Solar System are intriguing worlds in their own right. Until recently planetary scientists lacked any similar global-scale mosaics of these distant icy bodies in the outer Solar System, even though the latter had also been visited by various robotic spacecraft in recent decades. This situation began to change in 2010, with the publishing of the first-ever high-resolution global maps of Jupiter’s four largest moons, which were based on the treasure trove of data returned by NASA’s Galileo mission while the latter explored the Jovian system during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Now, thanks to the Cassini mission which has been studying Saturn for over a decade, scientists have acquired their first detailed color global mosaics of some of the ringed planet’s largest satellites as well.

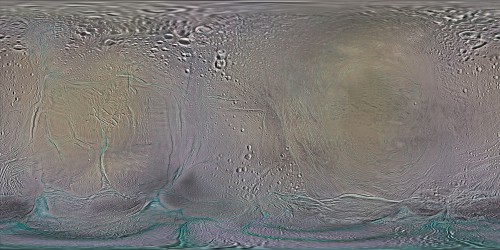

Akin to the iconic Pioneer and Voyager missions of the 1970s, Cassini can also be described as one of the most historic missions in the annals of planetary exploration. Following a seven-year journey throughout the Solar System, Cassini became the first spacecraft ever to enter into orbit around Saturn in July 2004. Shortly thereafter, it began an unprecedented study of the majestic ringed planet and its 62 moons, while returning images of ethereal cosmic beauty along the way that could be best characterized as a fusion of both science and art. Having passed the 10-year mark in its mission earlier this year, Cassini has already returned hundreds of gigabytes worth of data and hundreds of thousands of high-definition images of Saturn and its moons. Even though one of the mission’s primary science targets was mystifying Titan, Saturn’s planet-sized moon which is enshrouded in a thick, hydrocarbon-rich atmosphere, what really stole the show was tiny Enceladus, an inconspicuous icy moon orbiting at the edges of Saturn’s extensive ring system. During a series of close flybys of Enceladus, Cassini revealed the presence of an astonishing series of linear depressions at the moon’s south pole, nicknamed the “tiger stripes,” which were venting hundreds of kilograms of water ice and organic compounds each second into space, making it one of the more geologically active and astrobiologically interesting moons in the outer Solar System, with its potential to harbor an underground habitable environment.

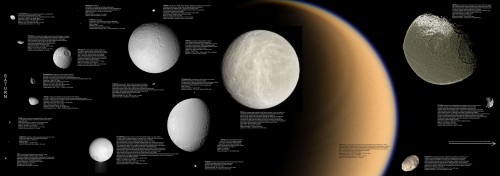

Not to be outdone, the rest of Saturn’s large icy moons exhibit a set of surprising and unexpected topographies. Indeed, some of the geologic formations that have been found on these moons are highly impressive and quite unique in the entire Solar System. Bearing a striking resemblance to the fictional Death Star from the “Star Wars” movie franchise, the 130-km-wide Herschel crater on Mimas is almost one-third the moon’s diameter, while 1,471-km-wide Iapetus resembles a giant walnut due to the presence of a 1,300-km-long ridge that spans the moon’s entire equator and was first observed by Cassini. Rhea, on the other hand, which is the second-largest moon of Saturn after Titan, has a heavily cratered terrain, while exhibiting two largely dissimilar hemispheres like Iapetus which suggest that extensive resurfacing events due to thermal heating must have taken place at some point in the moon’s history. The two other moons that round-up the list of Saturn’s large icy moons, Tethys and Dione, are heavily cratered like Rhea, yet their surface geology shows evidence of past tectonic activity which when ceased, caused their subsurface oceans to solidify. The surface features of these highly diversified moons have now come into clear view in a set of new global maps which have been compiled by Dr. Paul Schenk, a planetary scientist at the Lunar & Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas.

Beginning with Voyager 2 in the late 1970s, Dr. Schenk has actively participated in almost every major planetary mission that NASA had launched toward the outer Solar System in the following decades, including Galileo, Cassini, Dawn, and New Horizons. No stranger to planetary exploration, and having access to the vast amounts of data that were collected by the Galileo spacecraft, he meticulously created the first-ever detailed color global maps of Jupiter’s four largest moons—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—which were collectively published in his Atlas of the Galilean Satellites in 2010 by Cambridge University Press. “Younger than NASA by only 31 days, I followed the US into space along with Walter Cronkite and Jules Bergman on live TV, collecting newspaper and magazine clippings,” he would write in the book’s preface. “As awesome as the Apollo landings were to watch (I was but 10 years old), and the first Mars pictures of huge volcanoes and canyons that followed, it was the cold distant giant planets and especially their unfamiliar moons that were the great frontier of my imagination. The two Voyager spacecraft, launching in 1977, were the first true exploration of this frontier.”

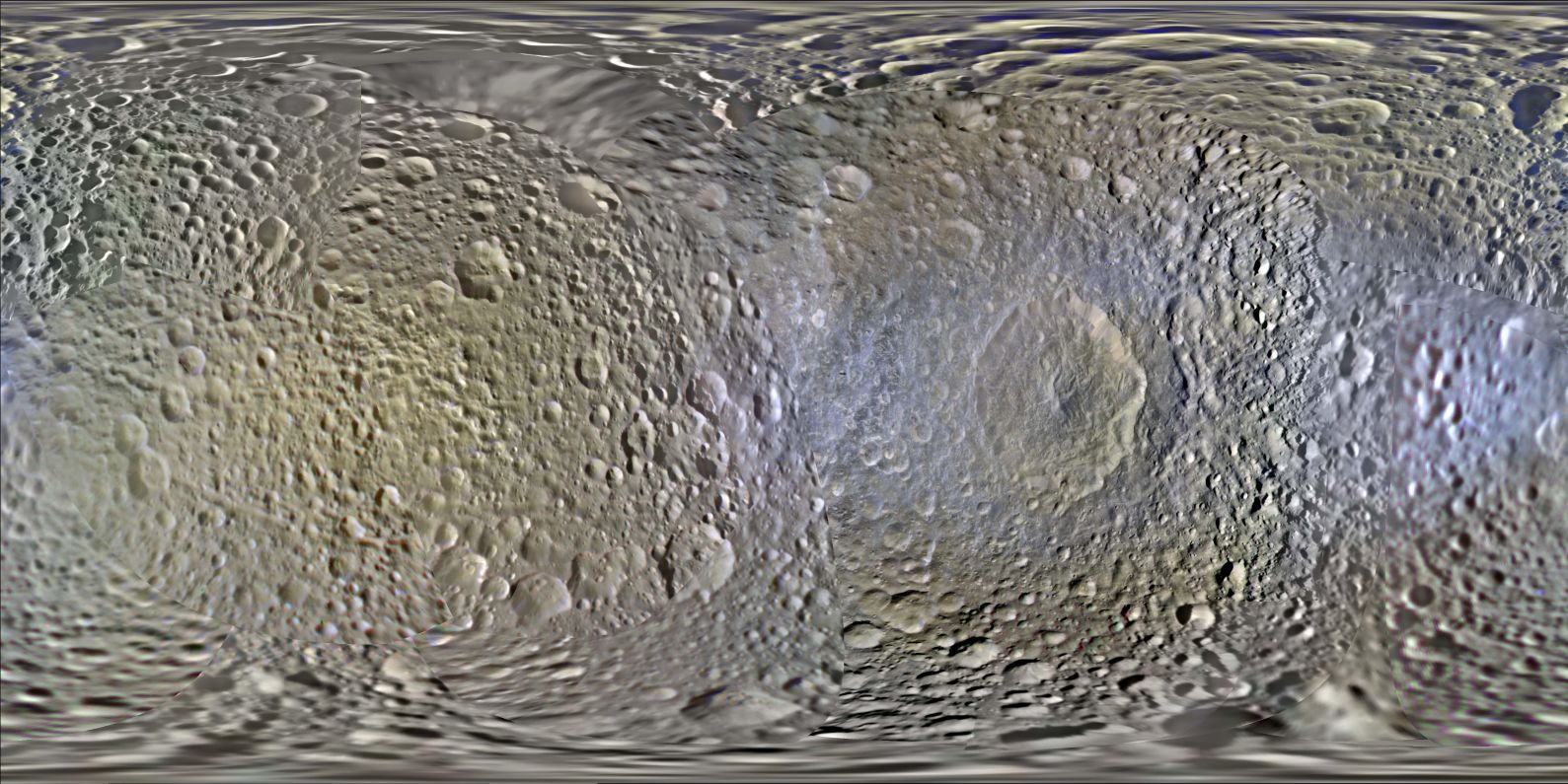

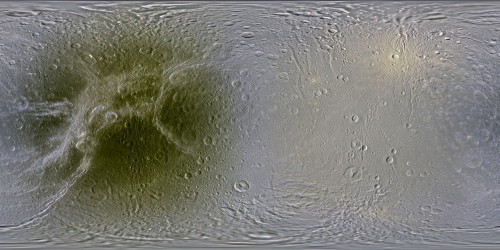

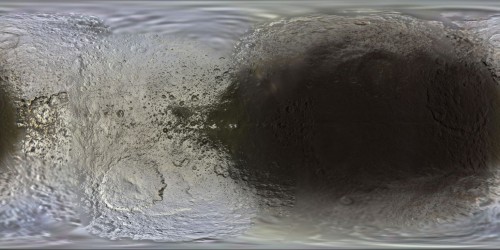

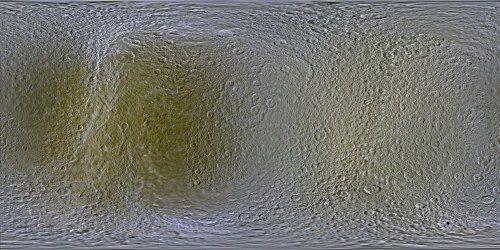

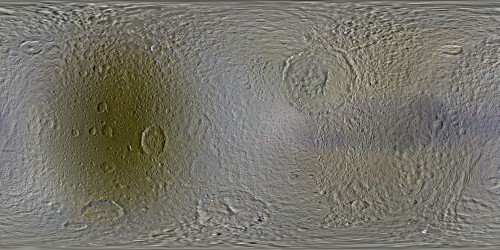

More recently, and following on the heels of his mapping of Triton which NASA released in a commemorative video for the 25th anniversary of Voyager 2’s Neptune flyby in August, Dr. Schenk completed the same task for Enceladus, Mimas, Rhea, Tethys, Dione, and Iapetus, after an 18-month-long intensive computer processing work of thousands of high-definition stereo images that were beamed back by the Cassini spacecraft. The results of this effort also signify the fulfillment of one of Cassini’s major science objectives: to produce the first full-color maps of Saturn’s largest icy moons. Contrary to the lower-resolution Voyager mosaics which only depict certain areas of the moons’ surfaces, Cassini’s high-resolution Imaging Science Subsystem truly revealed the entire moons in a new light. To that end, Cassini imaged the moons in various wavelengths, from the ultraviolet to the mid-infrared, during a series of close flybys which allowed for unprecedented resolutions of up to 400 meters per pixel for Rhea and Iapetus, 250 meters for Dione and Tethys, 200 meters for Mimas, and 100 meters for Enceladus. Furthermore, where in visible light the moon’s surface colors appear somewhat subdued, in Cassini’s multispectral images the former stand out with enhanced clarity, helping to bring out geologic features which were previously hidden. “These are the first global maps to realistically show brightness variations across the surface,” writes Schenk on his personal site. “Hence you can see the really dark trailing hemispheres of Tethys, Dione and Rhea very well. Bright lineations on Dione and Rhea also stand out as do various bright and dark features such as rayed craters … The other new feature of these maps is that they are the first accurate maps in color. These new maps are in ‘Superman’ colors, just beyond the range of normal human color vision. The natural visual colors of these bodies do reveal information but they tend to be rather bland. Cassini did obtain routine higher resolution coverage of these moons in the near-IR and the UV wavelengths and these are used to make the global maps. ‘Dialing up’ the colors to include these spectral ranges also brings out color contrasts between geologic features much better than the old R-G-B range.”

Global maps of Saturnian moons were produced by Dr. Paul Schenk (Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, Texas). Image data are from the Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) camera on the Cassini orbiter (NASA, JPL).

Some of the surface features that become readily apparent in these new maps include a series of contrasts in color between the moons’ leading and trailing hemispheres. For instance, the constant deposit of material on Enceladus’ surface that comes from the venting of the moon’s south polar water ice jets colors the terrain in yellow and magenta hues, indicating different thickness levels for these deposits. In addition, the fractures from which water ice escapes into space appear deep blue in ultraviolet wavelengths, sharing an uncanny resemblance to the blue ice which is found in Earth’s polar regions as well. The rest of the moons exhibit similar color differentiations, with the trailing hemispheres of Tethys, Rhea, and Dione appearing dark red due to the constant bombardment by charged particles from Saturn’s magnetosphere, while their leading hemispheres are coated in icy dust originating from the planet’s tenuous E ring which is constantly replenished by Enceladus’ water ice jets.

As has been the case with the global maps of the Galilean moons, which have proved to be of great scientific importance to planetary scientists, those of Saturn’s icy moons will similarly help researchers make new discoveries regarding the fascinating geologic history of these distant bodies in the outer Solar System. Yet, besides their scientific value, the global maps of the Solar System’s icy moons have a great aesthetic one as well, reminding us of their intrinsic beauty. “It is all well and good to use maps like these for scientific investigations,” comments Schenk. “That is why we go there, to learn about how the Solar System works. But sometimes it is worth stepping back for a few moments and marveling at the amazing Universe we are part of. Each world out there is unique and holds numerous discoveries and surprises. These worlds are also little jewels in a vast empty Cosmos, fascinating and wonderful to behold.”

In the end, it may be that we reach out into space not only for the sake of knowledge and understanding, but for the sake of beauty as well.

The maps can be downloaded from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory site here and from the Lunar and Planetary Institute site here.

Video Credit: Lunar and Planetary Institute

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Yet another excellent example as to why we need to continue exploration of the moons of Saturn and Jupiter. Do these colors suggest organic materials from deep within the moons along with water?

Great article, Leonidas!

Thank you Tom! Indeed, many color differences on Enceladus as revealed by these new maps, are associated with young fructures on the surface from which fresh material possibly rich in organic chemistry is released from the moon’s interior. Tethys is another moon which is coated with microscopic icy particles from Saturn’s tenuous E ring, which in turn is constantly replenished by Enceladus’ organic-rich, water ice plumes.

As you correctly point out, the exploration of the largely fascinating moon systems of Jupiter and Saturn should be a priority. Who knows what else is there to discover as well?