Twenty-five years ago, this month, an African-American astronaut commanded one of the most pivotal missions in U.S. spaceflight history. Charlie Bolden—veteran of three previous flights, including the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST)—led the crew of shuttle Discovery on an eight-day mission whose primary objective was scientific research and satellite deployment and retrieval. In this sense, STS-60 closely mirrored many previous flights of the shuttle era.

But for Bolden, who would go on to become the first African-American administrator of NASA (under the leadership of the first African-American President), it marked a milestone, for it included both Russian and U.S. crew members for the first time since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP). In commanding STS-60, Bolden was not only forging a path to future co-operation with Russia, but was also continuing a long line of contributions made by African-American astronauts in space.

Throughout February, as the United States observes Black History Month, we are reminded not only of Bolden’s accomplishment, but of all 14 African-Americans who spent time in space between August 1983 and March 2011. And we are reminded of those who will follow in their footsteps, including Victor Glover, currently training for the first dedicated crew-exchange mission aboard SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, later this year.

And, of course, we are reminded of those who strived for space, but never made it home: Challenger’s Ron McNair, Columbia’s Mike Anderson and Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) astronaut Bob Lawrence, who—had the hands of fate turned with greater kindness—might have become the first African-American to fly into space and maybe even the first black Space Shuttle commander.

Lawrence died, aged 32, whilst flying backseat as an instructor pilot on the F-104 Starfighter in December 1967; had he lived, he would likely have joined fellow MOL research pilots Karol “Bo” Bobko, Bob Crippen, Gordo Fullerton, Bob Overmyer, Don Peterson, Dick Truly and Hank Hartsfield in being selected by NASA as members of its seventh class of astronauts in September 1969. And since all but Peterson went on to fly as pilots and commanders of the shuttle, it is highly probable that Lawrence might have flown in the front seat of one of the orbiters at some point in the early 1980s.

As circumstances transpired, the first spacefarer of African ancestral heritage who actually made it to space was Cuba’s Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez, who flew an eight-day mission with Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Romanenko in September 1980. Aboard Soyuz 38, the pair docked with the Salyut 6 space station and worked for several days alongside the resident crew, Soviet cosmonauts Leonid Popov and Valeri Ryumin. By the time of Tamayo Méndez’s flight, however, NASA had already selected no fewer than four African-American men for astronaut training in anticipation of the forthcoming shuttle program. In January 1978, Air Force officers Guy Bluford and Fred Gregory and civilian physicist Ron McNair were picked in the first class of shuttle astronauts, with Marine Corps aviator Charlie Bolden chosen in May 1980.

With such emphasis upon diversity within the previously all-white astronaut corps, it was unsurprising that one of these African-American candidates drew an early shuttle crew assignment. In April 1982, NASA named Bluford to STS-8, then planned for mid-1983 to deploy a large Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS). However, problems with the satellite’s booster caused it to be scrubbed from the mission and STS-8 picked up a new payload: an Indian communications satellite and a large payload flight test article, resembling a giant dumb-bell, to test the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robotic arm.

STS-8 began on 30 August 1983, becoming the first shuttle mission to launch at night, and Bluford—in the center seat, behind the commander and pilot, serving as flight engineer—later remembered that the excitement took over and he laughed and chuckled almost the whole way into orbit. It was the dawn of a stellar career for Bluford. Subsequent assignments saw him lead the science crew for the first German-dedicated Spacelab mission in late 1985, before receiving two complex flights for the Department of Defense in 1991 and 1992.

Six months after Bluford’s first flight, Ron McNair launched on STS-41B, assisting with the deployment of two communications satellites and supporting the first untethered spacewalks in history, courtesy of Martin Marietta’s Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU). Two years later, in January 1986, he was tragically killed when Challenger broke apart in the cold Cape Canaveral sky, just 73 seconds after launch.

In April 1985, Fred Gregory—who went on to become NASA’s deputy administrator—became the first African-American to pilot a space mission, when he rode the front-right seat aboard STS-51B, a weeklong Spacelab flight. He subsequently commanded two Department of Defense missions in 1989 and 1991, becoming the first black astronaut to lead a spaceflight. In his NASA oral history, Gregory recalled being unconcerned about any “historic” element of the assignment; he was simply doing his job.

And in January 1986, just days before the loss of Challenger, Charlie Bolden piloted Columbia and might have flown again later that same year to deploy Hubble. As circumstances transpired, Bolden remained attached to the Hubble mission, which finally flew in April 1990, and later commanded two missions of his own: an Earth atmospheric research mission in early 1992 and the joint flight with the Russians in February 1994. Like Gregory, he rose to the higher echelons of NASA, becoming its first African-American administrator during the incumbency of President Barack Obama.

With the resumption of shuttle operations in the wake of the Challenger tragedy, black astronauts increasingly played their part. In September 1992, the first African-American woman—medical doctor Mae Jemison—flew aboard Spacelab-J, a co-operative mission between the United States and Japan, and in February 1995 another physician, Bernard Harris, became the first black person to perform a spacewalk. He spent four hours and 39 minutes working outside shuttle Discovery on STS-63, a mission which also earned its place in the history books by completing a rendezvous with Russia’s Mir space station.

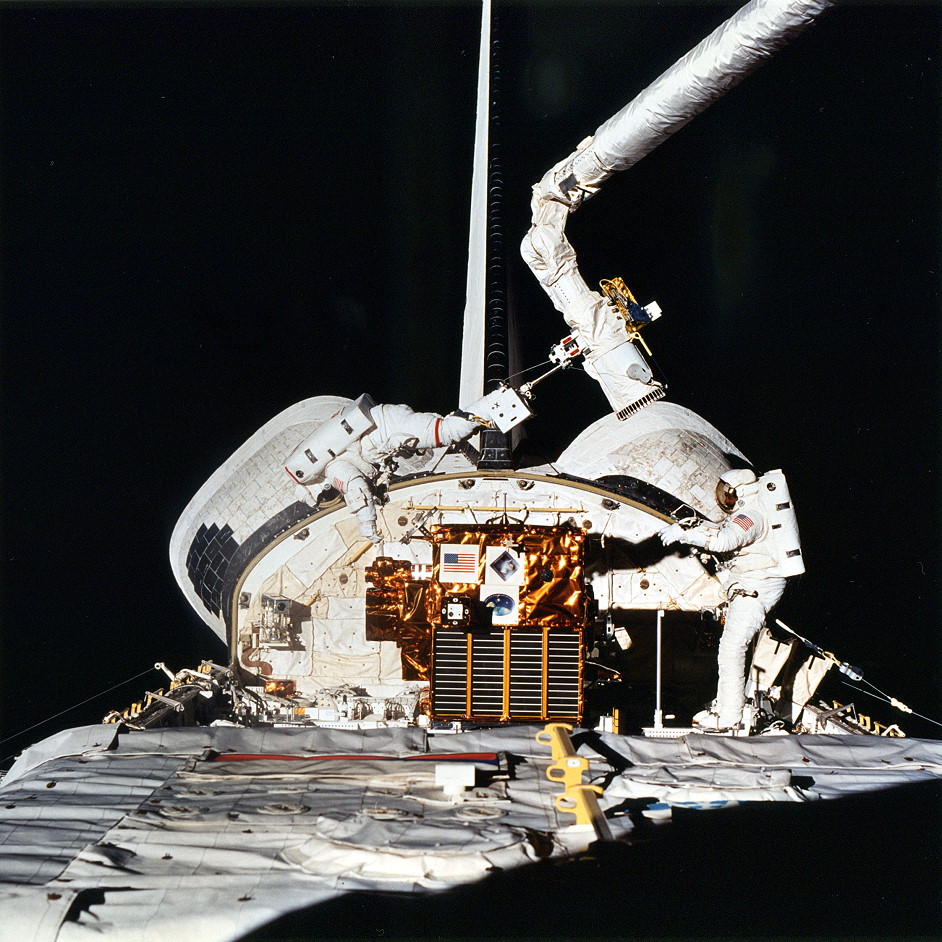

Spacewalking would also be conducted by African-American astronauts Winston Scott, Bob Curbeam, Bobby Satcher and Al Drew. Between them, these four men logged 14 sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA), totaling over 90 hours spent working outside their respective spacecraft in orbit.

Curbeam, with seven EVAs under his belt, remains the most experienced African-American spacewalker, having logged 45 hours and 33 minutes across a career which has included the delivery of the U.S. Destiny lab in early 2001 and the end-to-end rewiring of the International Space Station’s electrical grid in December 2006.

Other seasoned spacefarers include Stephanie Wilson—currently the world’s most flight-experienced African-American astronaut, with 42 days and 23 hours across three shuttle missions—and Joan Higginbotham, both of whom participated in several high-profile construction flights to the space station, together with Mike Anderson, the only African-American astronaut to board Mir, who later lost his life in the Columbia disaster in February 2003. Leland Melvin, who took primary responsibility for the delivery of Europe’s Columbus lab to the ISS in February 2008, went on to serve as NASA’s associate administrator for education.

We should also not forget those African-American candidates who were considered for spaceflights, but who never actually flew. In the early 1960s, during America’s pioneering days of space exploration, Air Force pilot Ed Dwight was briefly considered for astronaut training. And in the 1980s, Air Force officer Livingston Holder trained for a spot on a classified shuttle mission as a Manned Spaceflight Engineer (MSE), whilst Michael Belt served as backup payload specialist for STS-44 in late 1991.

More recently, assigned crewmember Jeanette Epps was controversially pulled from an ISS expedition last year, in what might have made her the first black person to fly a long-duration mission to the space station. That accolade looks set to go instead to Victor Glover, when he flies a SpaceX Crew Dragon, possibly in the second half of 2019.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.