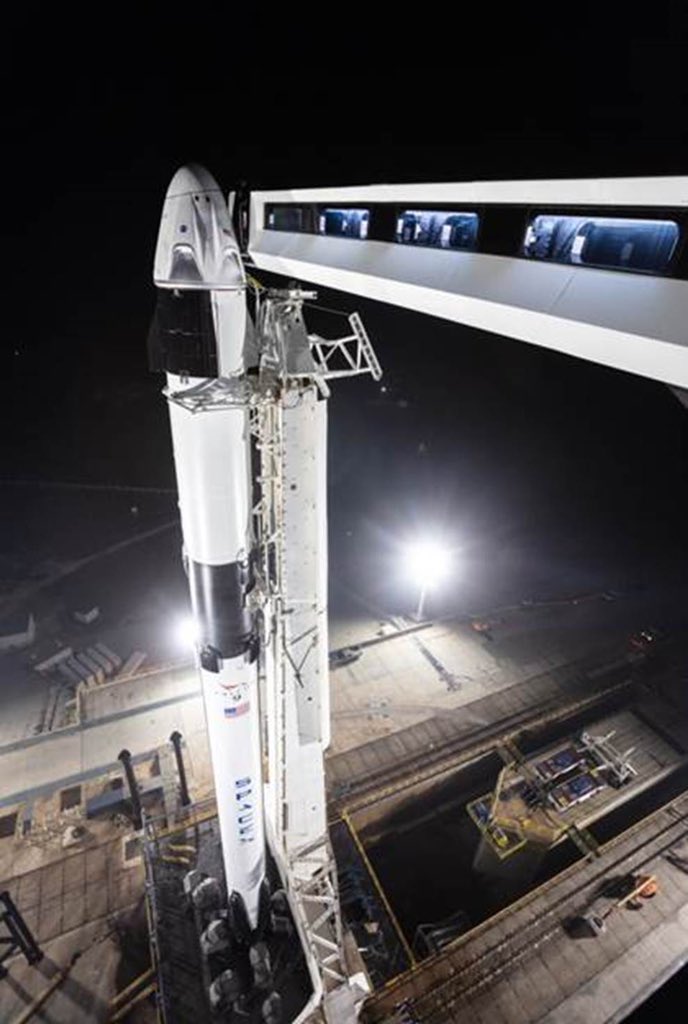

If all goes well, later this year America will jointly celebrate not only 50 years since humanity’s first manned landing on the Moon, but also the return to U.S. soil of human spaceflight launch capability, for the first time since the end of the Space Shuttle era. Current plans call for the first piloted Crew Dragon—carrying veteran shuttle flyers Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken—to launch from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, as soon as this summer, on a two-week test-flight to the International Space Station (ISS).

But before the first ‘Dragon Riders’ can fly, the spacecraft needs to conduct an uncrewed flight test to and from the ISS on the “Demo-1” mission.

It’s the culmination of a decade-long effort to provide U.S. crew access to the ISS via commercial entities, and both NASA and SpaceX now stand primed for that inaugural unpiloted test of Crew Dragon, which recently sailed through its Flight Readiness Review (FRR) with flying colors and is currently targeted to launch no sooner than 2:48 a.m. EST on Saturday, 2 March.

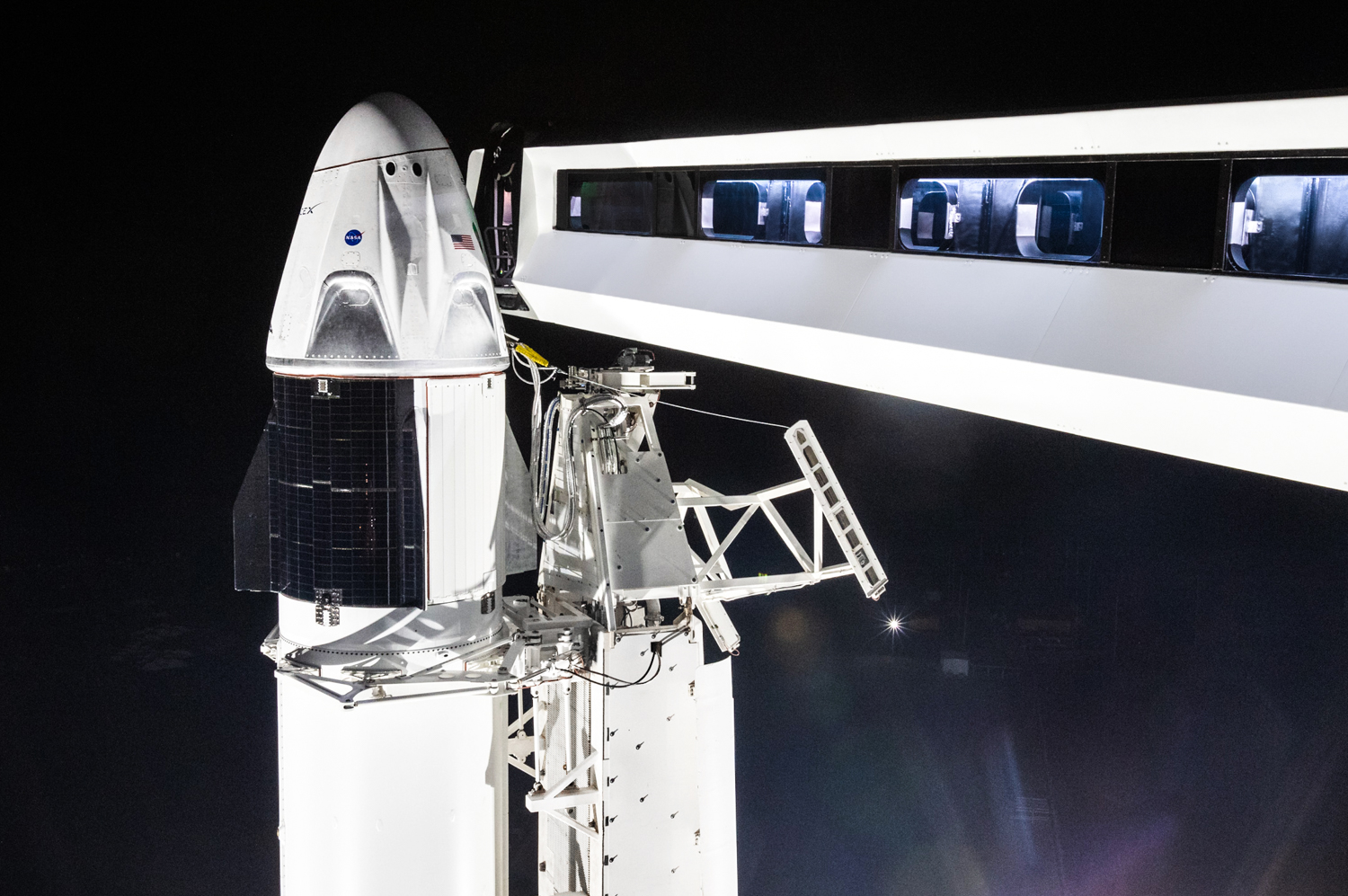

Mounted atop a first-time-flown Block 5 core (designated “B1051”), Demo-1 underwent a Static Fire Test at Pad 39A on 24 January, which cleared a significant hurdle in preparation for this ambitious mission. As noted by AmericaSpace’s Mike Killian, it represented the first occasion that a crew-capable vehicle and associated ground-support infrastructure had been integrated on the veteran launch pad since shuttle Atlantis began her swansong STS-135 flight back in July 2011.

According to NASA, an on-time launch Saturday will achieve a rendezvous and arrival at the space station—docking at International Docking Adapter (IDA)-2, situated on the forward end of the Harmony node—at 6:05 a.m. EST Sunday, 3 March. Hatches will be opened shortly thereafter and Expedition 58 crew members Oleg Konenenko, David Saint-Jacques and Anne McClain will unload around 400 pounds (180 kg) of equipment and supplies from the spacecraft.

Five days later, Demo-1 will undock from the ISS and perform a deorbit “burn” to commence a 30-minute hypersonic descent back through Earth’s atmosphere, parachuting to a splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean.

ABOVE: Watch the full Post-Flight Readiness Review briefing for the Demo-1 mission

The U.S. Air Force 45th Space Wing’s launch weather forecast calls for an 80% chance of favorable conditions for the March 2 attempt, with a 20% chance of some cloud cover violating launch commit criteria.

.

Follow our LAUNCH TRACKER for updates & LIVE COVERAGE of the launch!

.

Another launch attempt is scheduled for Tuesday, March 5 at 1:30am EST, if needed. USAF notes a less favorable 60% GO for launch that night, as a cold front is expected to hover over Florida early next week.

—————————————————————————————

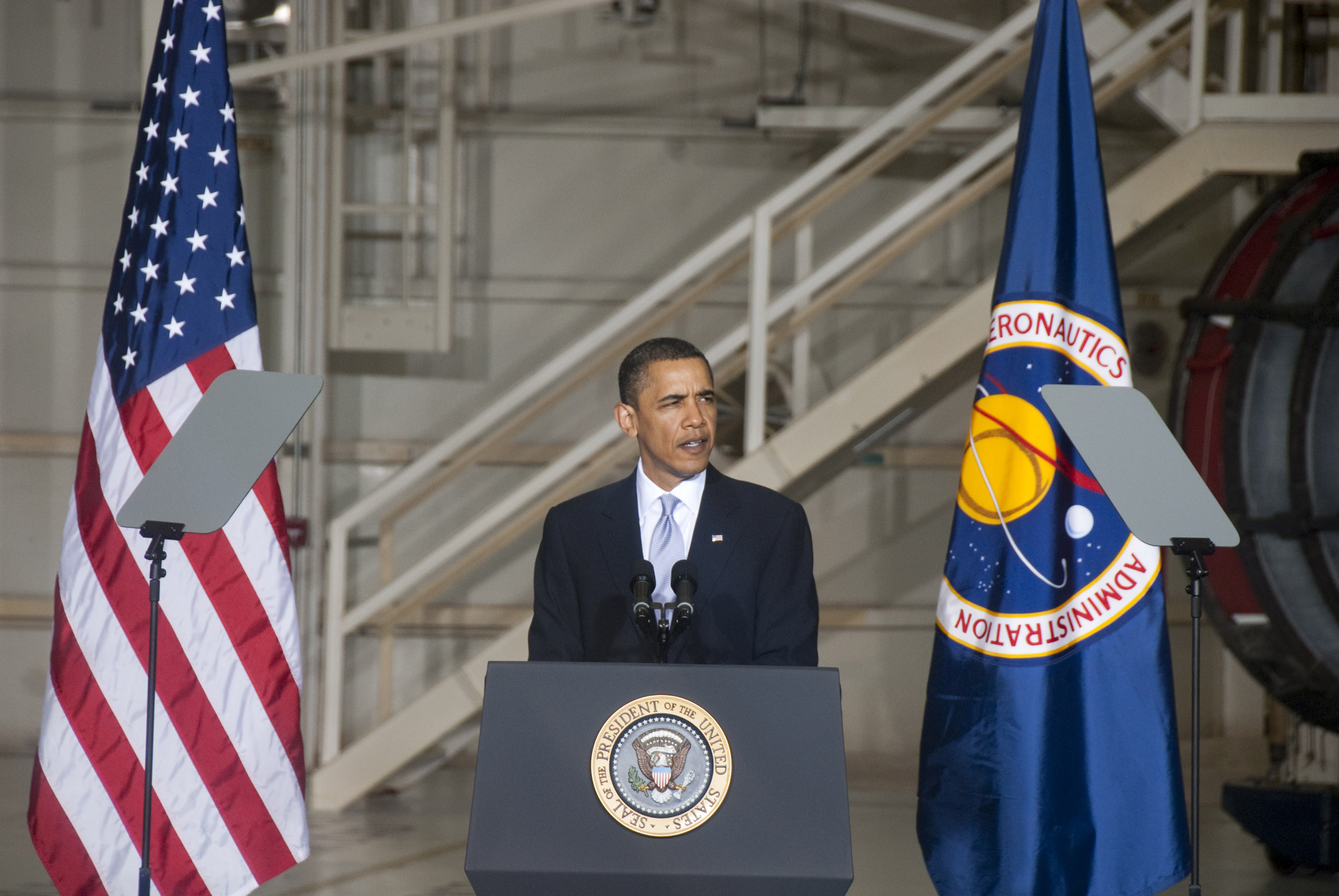

To put it mildly, it has been a long, tortured and convoluted journey for NASA and SpaceX to reach this point. Following then-President Barack Obama’s April 2010 space policy directive—which called for the fabrication of a super-heavylift booster for Beyond Low-Earth Orbit (BLEO) missions and the courting of commercial players to build ISS crew vehicles—a cadre of organizations were awarded Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) funding, as part of an ongoing drive to stimulate the U.S. aerospace industry to develop and demonstrate human spaceflight capabilities. In April 2011, SpaceX won $75 million in funding for a crewed variant of its Dragon cargo ship through the second round of CCDev solicitations.

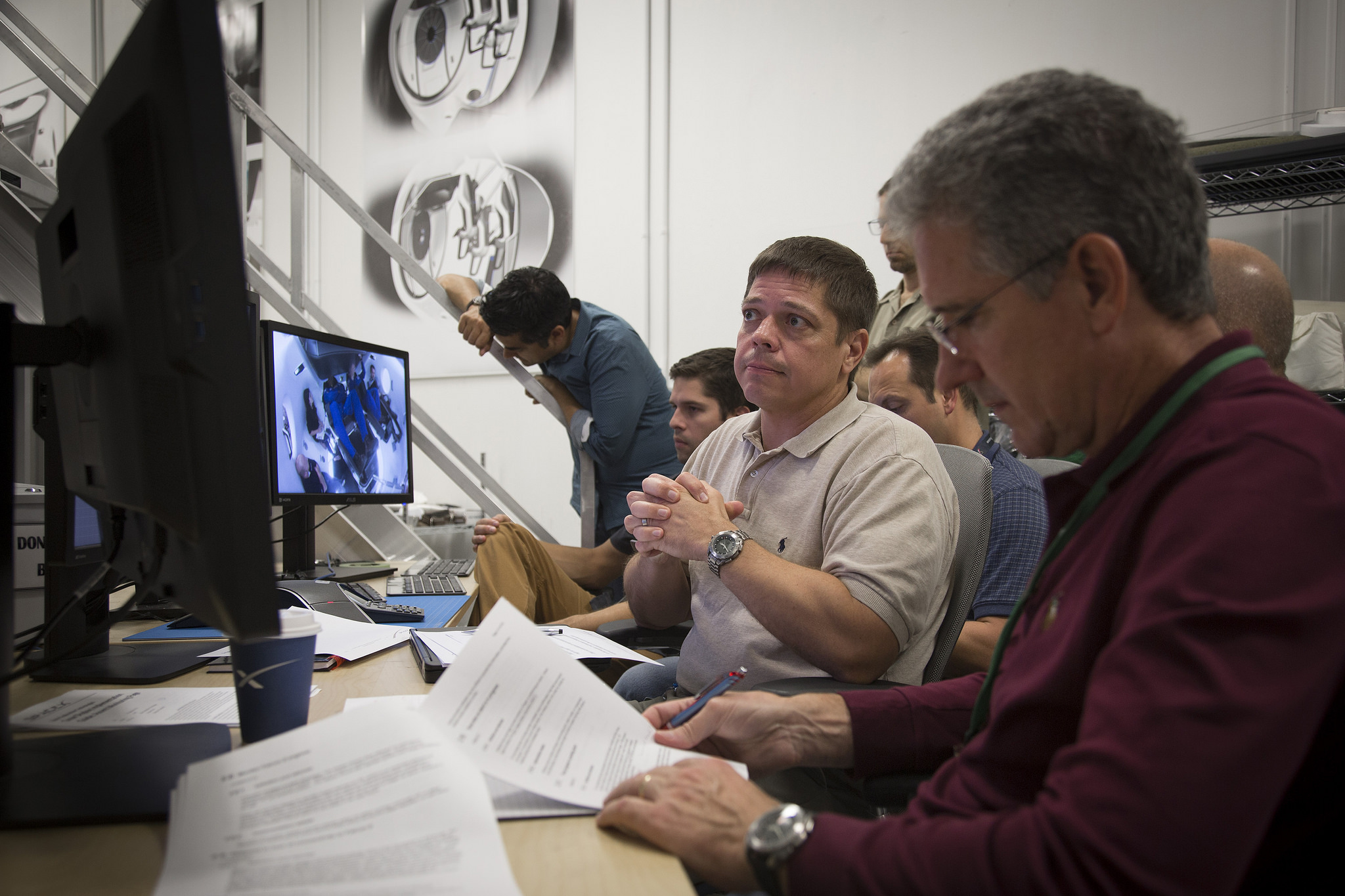

By the summer of the following year, joint NASA-SpaceX teams had thoroughly evaluated the Crew Dragon’s proposed capabilities, including its environmental control and life-support systems, its conceptual displays and controls, its cargo racks and interior systems, as well as its seating and lighting provisions. “Human-factors” evaluations were conducted by veteran shuttle astronauts Rex Walheim, Tony Antonelli, Eric Boe and Tim Kopra, who practiced entering and exiting the Dragon mockup under nominal and contingency situations, as well as reaching and handling spacecraft controls.

SpaceX was one of three finalists—alongside Boeing and Sierra Nevada Corp. (SNC)—to win coveted Commercial Crew integrated Capability (CCiCap) funding in August 2012. The Hawthorne, Calif.-headquartered launch services organization was awarded a contract worth $440 million, as part of an effort which should have seen U.S. astronauts returned to space from U.S. soil by 2017.

As NASA commended SpaceX’s “diligence” and the SpaceX founder Elon Musk expressed personal conviction that piloted Crew Dragon flights would be underway by the middle of the decade, the Congressional funding reality for the Commercial Crew Program was far less optimistic and it became clear that such schedules were unachievable. In both 2010 and 2011, NASA contracted extensively (and expensively) with Russia for seats aboard its Soyuz spacecraft to assure U.S. access to the space station in the 2013-2016 timeframe, and was obliged to do so again in April 2013 to cover the 2016-2017 period.

More recently, in August 2015, as the Commercial Crew effort continued to receive ever-lower levels of funding, a clearly irritated NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden was forced to purchase additional Soyuz seats to cover the timeframe through 2019.

Nevertheless, the CCiCap finalists pressed on with the maturation of their spacecraft designs. SpaceX completed its first three milestones—a technical baseline review of the Crew Dragon and its Falcon 9 booster, an overall CCiCap milestone achievability review and an integrated systems requirements review to demonstrate its processes and procedures for designing, building and testing the spacecraft—by November 2012.

By the end of the year, the first phase of a multi-phase campaign to certify the spacecraft against NASA’s flight safety and cost-effectiveness requirements began in earnest. This process included reviews of the ground systems, ascent, on-orbit and entry phases of a Crew Dragon mission and in November 2013 NASA and SpaceX engineers and safety specialists turned their attention to the integrated Falcon 9 booster. Early the following year, SpaceX signed a 20-year lease for historic Pad 39A to launch Crew Dragon and other commercial missions.

Finally, on 16 September 2014, SpaceX and Boeing were formally selected by NASA to progress towards actually building the spacecraft. “Today, we are one step closer to launching our astronauts from U.S. soil on American spacecraft and ending the nation’s sole reliance on Russia by 2017,” said Bolden. “Turning over low-Earth orbit transportation to private industry will also allow NASA to focus on an even more ambitious mission: sending humans to Mars.”

All told, the Commercial Crew transportation Capability (CCtCap) contracts totaled $6.8 billion, of which $2.6 billion went to SpaceX to complete the development of Crew Dragon. Under the terms of the contract, both partners—with Boeing fabricating its CST-100 Starliner vehicle for Commercial Crew operations—would be required to conduct at least one piloted test-flight, with NASA astronauts aboard, to verify their ability to launch aboard a fully integrated rocket and spacecraft system, maneuver in orbit, rendezvous and dock with the ISS and return safely to Earth.

When this certification was complete, Boeing and SpaceX could anticipate at least two (and as many as six) dedicated crew-rotation missions to the space station, supporting ISS residents as a lifeboat for up to seven months at a time.

By December 2014, SpaceX had satisfactorily completed a certification baseline review of its Crew Dragon hardware, outlining its spacecraft fabrication methodologies and—in the words of NASA Commercial Crew Program manager Kathy Lueders—setting “pace for the rigorous work ahead”. The company also described its approach to securing NASA certification for flying astronauts and the newly-leased Pad 39A was formally identified as the launch site for the first Crew Dragon missions.

First utilized for the maiden voyage of the Saturn V lunar rocket, back in November 1967, the 39A complex had seen off all but one of the Moon-bound crews of Apollo astronauts, together with the Skylab space station and dozens of shuttle flights, including the last one, STS-135.

For the Commercial Crew Program, 2014 had proven a hugely successful year, with no fewer than 23 milestones and thousands of hours of technical reviews accomplished. Yet in spite of the conviction of NASA and the partners that the first flights were achievable by 2017, reality would conspire against Commercial Crew and a far longer road to launch still lay ahead.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Missions » ISS » CCDev » DM-1 »

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Crew Dragon Kicks Off Demo-1 Mission to Return Human Spaceflight to American Shores « AmericaSpace