In a major step towards its maiden voyage later this year, United Launch Alliance (ULA) conducted a successful Flight Readiness Firing (FRF) of the Vulcan-Centaur core stage late Wednesday evening. Closely monitored by ULA teams at Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., the FRF demonstrated day-of-launch timelines and procedures, propellant loading milestones and a full countdown protocol, followed by a six-second ignition, ramp-up, stable period of thrust and controlled shutdown of Blue Origin’s two BE-4 engines. Engineers will now work to examine the FRF data as ULA readies for Vulcan-Centaur’s certification mission, designated “Cert-1”.

Last night’s success marks the culmination of several months of intensive activity through 2023’s opening half. The 109.2-foot-long (33.3-meter) core stage, the 18.8-foot-tall (5.7-meter) interstage adapter—with its trademark Stars and Stripes flag—and Centaur V upper stage arrived at the Cape on 21/22 January.

All three components had made the 2,000-mile (3,200-kilometer) river-and-seagoing voyage over a little more than a week from ULA’s factory in Decatur, Ala., to the Cape, aboard the R/S RocketShip vessel. In the final week of January, the Launch Vehicle On Stand (LVOS) milestone got underway at SLC-41.

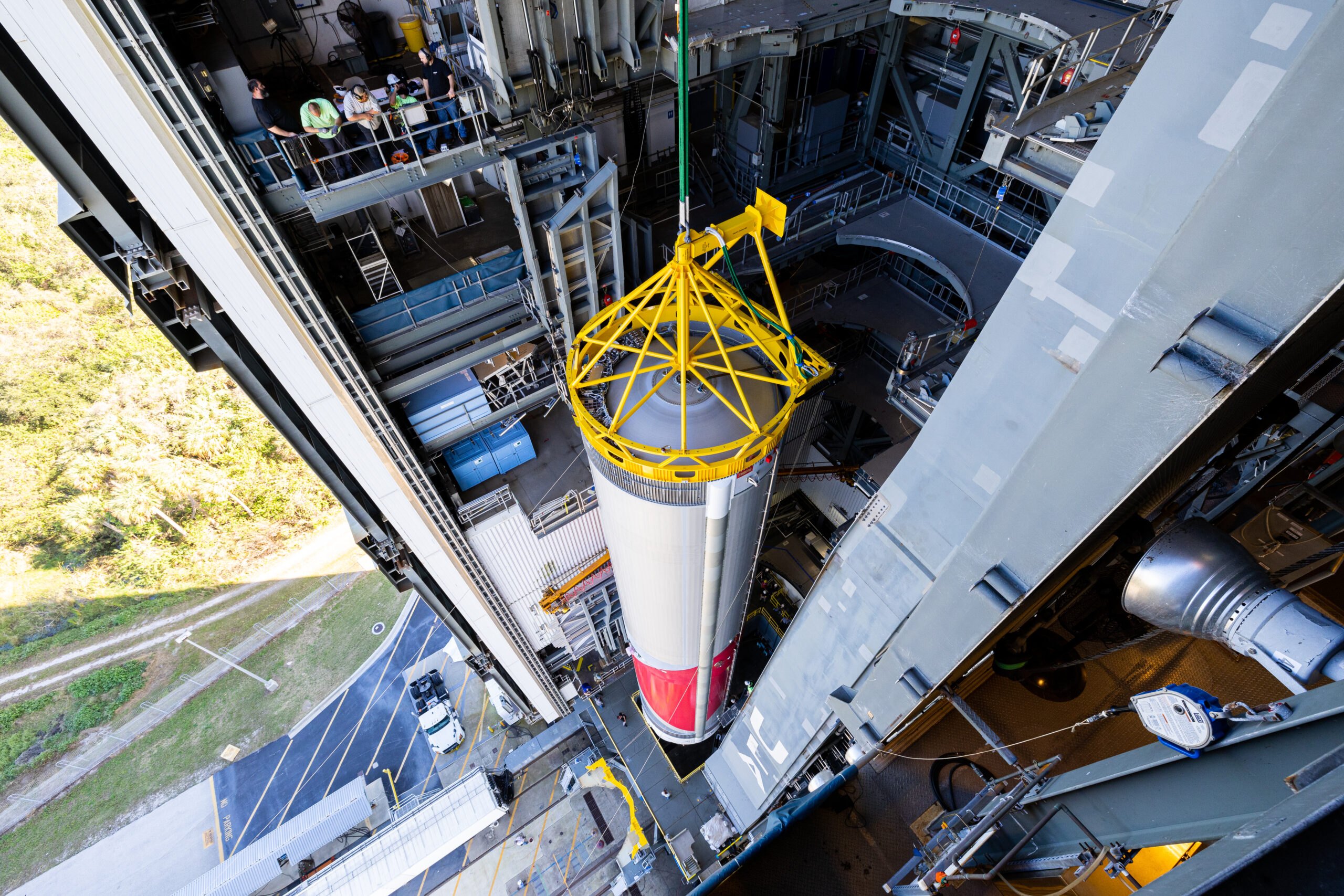

Firstly, the core stage—emblazoned with its beautiful red, white and gray Vulcan livery—was hoisted atop four support fixtures on the Vulcan Launch Platform (VLP) in the 286-foot-tall (87-meter) Vertical Integration Facility (VIF) for a series of tests ahead of Cert-1. Next, the 38.5-foot-long (11.7-meter) Centaur V was added to the stack in early February, allowing ULA personnel to enter integrated testing inside the VIF.

By this point, Vulcan-Centaur’s Cert-1 launch had slipped from April until no sooner than May 2023. In the second week of March, the stack rolled a quarter-mile (400 meters) from the VIF to the SLC-41 pad surface for “tanking” tests.

On 10 and 16 March, teams loaded about 1.1 million pounds (450,000 kilograms) of liquid oxygen and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) propellants aboard the Vulcan core stage and liquid oxygen and hydrogen into the Centaur V. This served to validate systems, loading protocols and procedures and terminated with the drainage of both fuel and oxidizer and “safing” of the stack, before returning to the VIF.

Last month, the Vulcan-Centaur was back at the pad for the Flight Readiness Tanking Test (FRTT) and—originally targeted for 25 May—the FRF itself. But teams elected to stand down from test-firing the two BE-4 engines, having observed “a delayed response from the booster engine ignition system” which required “further review”.

The stack was returned to the VIF to allow engineers access to the booster ignition system. Late on Tuesday, the stack was back at SLC-41 for a second attempt.

Led by ULA Launch Conductor Dillon Rice, on Wednesday afternoon the vehicle was fully loaded with cryogens and put through the final seven minutes of day-of-launch operations—the “Terminal Count”. But T-0 for the FRF was repeatedly delayed throughout the evening, firstly to 6:45 p.m. EDT, then past 9 p.m. EDT.

“Had a lightning event during the planned hold,” tweeted ULA CEO Tory Bruno. “Triggered a redline and re-test criteria. Recycling and heading back into the count soon.”

Weather conditions for the FRF were highly favorable, with mild ground winds of 5.7 mph (9.1 km/h), temperatures of 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Fahrenheit) and light southerly-blowing winds. The vehicle transitioned to Internal Power at T-2 minutes and the Flight Termination System (FTS) was armed a few seconds later.

“Ground Vent Valves secured” came the call at T-16 seconds, followed by a clipped “Go for FRF”.

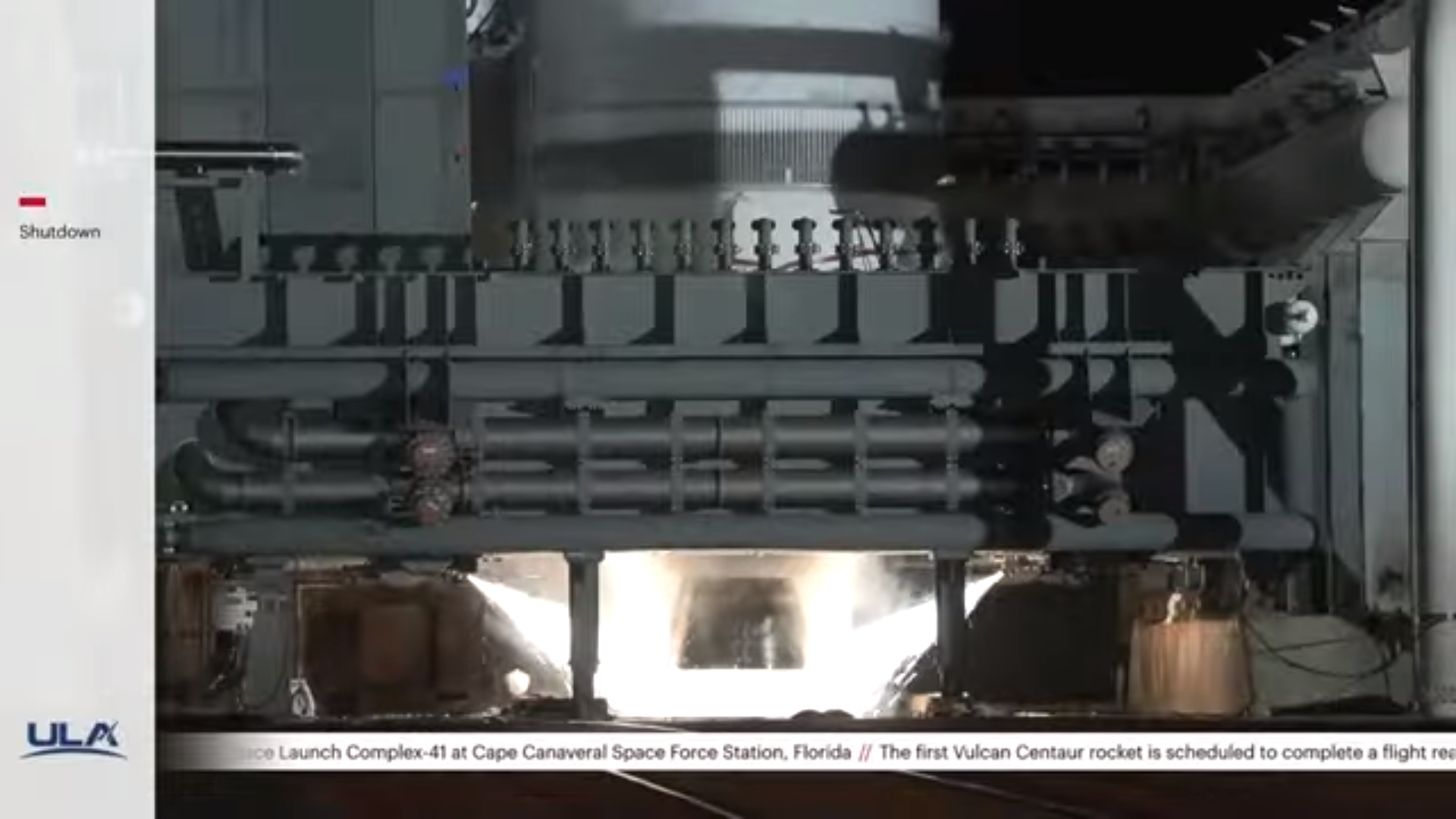

At 9:05 p.m. EDT, the two BE-4 engines roared to life, rocking the Space Coast with 1.1 million pounds (500,000 kilograms) of thrust. Engine Start occurred at T-4.88 seconds.

This was followed by a rapid throttle-up to the target level for about two seconds of stable thrust, before shutting down. The entire FRF lasted six seconds.

“Nominal run,” tweeted Mr. Bruno, in the aftermath of the test.

“We are more than 98 percent complete with the Vulcan qualification program and the remaining items associated with the final Centaur V testing,” ULA later reported. “The team is reviewing the data from the systems involved in today’s test. Pending the data review…we will develop a plan for launch.”

As that plan crystallizes, the Vulcan-Centaur’s pair of strap-on GEM-63XL solid-fueled boosters, built by Northrop Grumman Corp., will be added to the base of the core stage, followed by the payload fairing. Combined with Blue Origin’s twin BE-4 engines, this will yield a liftoff thrust for Cert-1 of a little over 2.1 million pounds (950,000 kilograms).

For Cert-1, the new rocket will deliver Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander with 77 pounds (35 kilograms) of customer payloads to the Moon under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. When launch contracts for this mission were signed back in July 2017, it was hoped that Peregrine would launch as early as 2019, “during the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11”, but it was not to be, as the development of the Vulcan-Centaur shifted inexorably to the right.

By September 2018, Cert-1 had slipped to mid-2020 at the soonest. And with the completion of the system-level Critical Design Review (CDR) in May 2019—as Vulcan transitioned from its design phase into formal qualification—that No Earlier Than (NET) target had shifted yet again, with an expectation that it would take place “in less than two years”, no sooner than the late spring of 2021, a date which continued to fall seemingly further and further away.

In tandem with efforts to develop the new rocket, the hardware at SLC-41 has been extensively rebuilt and reconfigured from its previous role supporting ULA’s Atlas V fleet. A large LNG storage area was installed, the acoustic sound suppression water system at the pad underwent substantial upgrades and new liquid oxygen and hydrogen tankage was added. Modifications were made to the VIF to handle the largest and most powerful Vulcan-Centaur configuration—with up to six GEM-63XL strap-on boosters—and the 183-foot-tall (55.8-meter), 1.3-million-pound (590,000-kilogram) Vulcan Launch Platform was built.

In addition to Peregrine, the Cert-1 mission will carry a pair of prototype Project Kuiper global broadband satellites, flying as part of a broader launch contract with Amazon. In April of last year, Amazon selected ULA’s Vulcan-Centaur for 38 launches to deliver a “constellation” of 3,236 Project Kuiper satellites into orbit to make high-speed, low-latency broadband internet provision “more affordable and accessible for unserved and underserved communities”—including households, schools, hospitals, businesses and government agencies—around the world.

4 Comments

4 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:Vulcan-Centaur completes ready-to-fly fire as Cert-1 mission nears

Pingback:ULA “Go” for Wednesday Pre-Dawn NROL-68 Launch - AmericaSpace

Pingback:ULA Launches Third Mission of 2023, Looks Ahead to Maiden Vulcan Flight - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Vulcan-Centaur Stacking Underway, ULA Aims for Christmas Eve Launch - AmericaSpace