After almost a full decade in development, United Launch Alliance (ULA) is only days away from “Cert-1”, the long-awaited maiden certification voyage of its mammoth Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter, currently targeted to fly from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., at 2:18 a.m. EST on Monday, 8 January. Aboard the 202-foot-tall (61-meter) behemoth—which ultimately will replace ULA’s in-service Atlas V and soon-to-be-retired Delta IV rocket fleets—is Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander with 77 pounds (35 kilograms) of customer cargo to the surface of the Moon under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program and the “Enterprise Flight” memorial payload for Celestis, Inc.

The Launch Readiness Review (LRR), led by ULA Launch Director Tom Heter III, was completed on Thursday at the Cape’s Advanced Spacecraft Operations Center (ASOC), producing a definitive “Go” for launch. At the end of the review, senior leaders were polled for their readiness and signed the Launch Readiness Certificate. Current estimates are for 85-percent weather favorability in the early part of Monday morning.

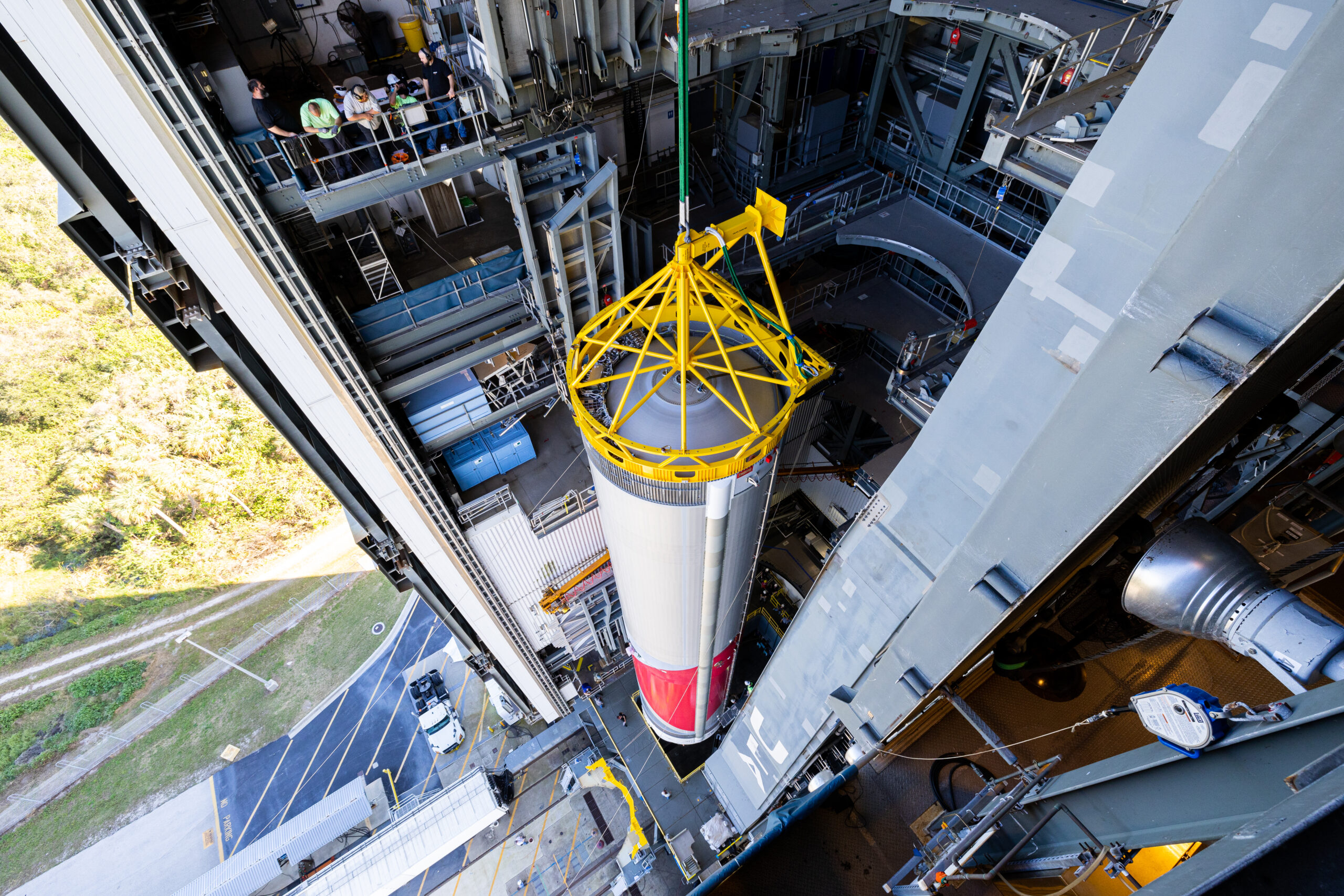

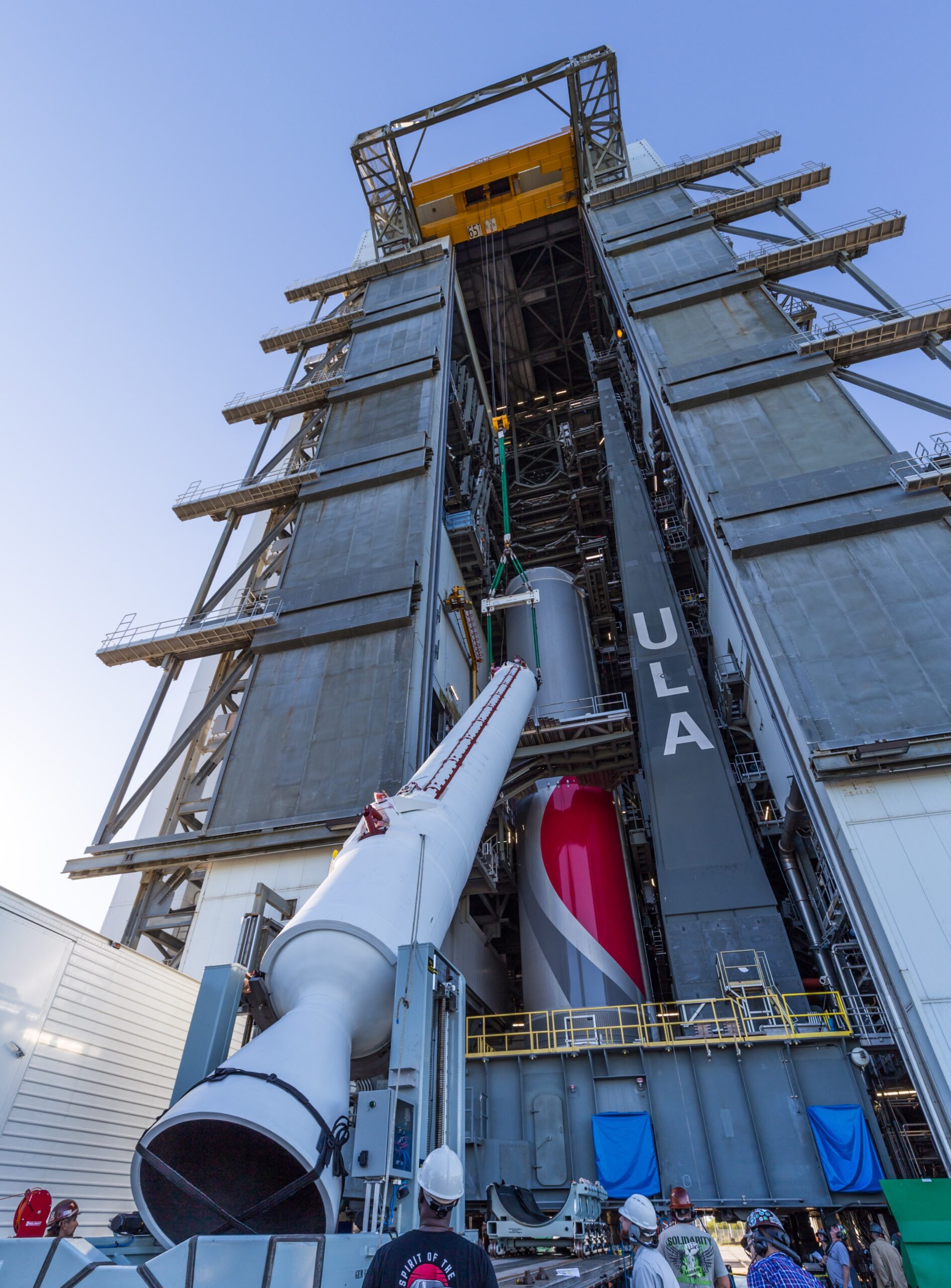

Formalized stacking operations of the Vulcan-Centaur commenced last 26 October, when the rocket’s core stage—emblazoned in its red and white Vulcan livery—was hoisted vertical and positioned atop the Vulcan Launch Platform (VLP) at SLC-41’s 286-foot-tall (87-meter) Vertical Integration Facility (VIF). And over a week-long period, the twin Northrop Grumman Corp.-built Graphite Epoxy Motor (GEM)-63XL solid-fueled boosters were affixed to the base of the core stage, providing a “business end” of Cert-1 that will punch out 2.1 million pounds (950,000 kilograms) of thrust at T-0.

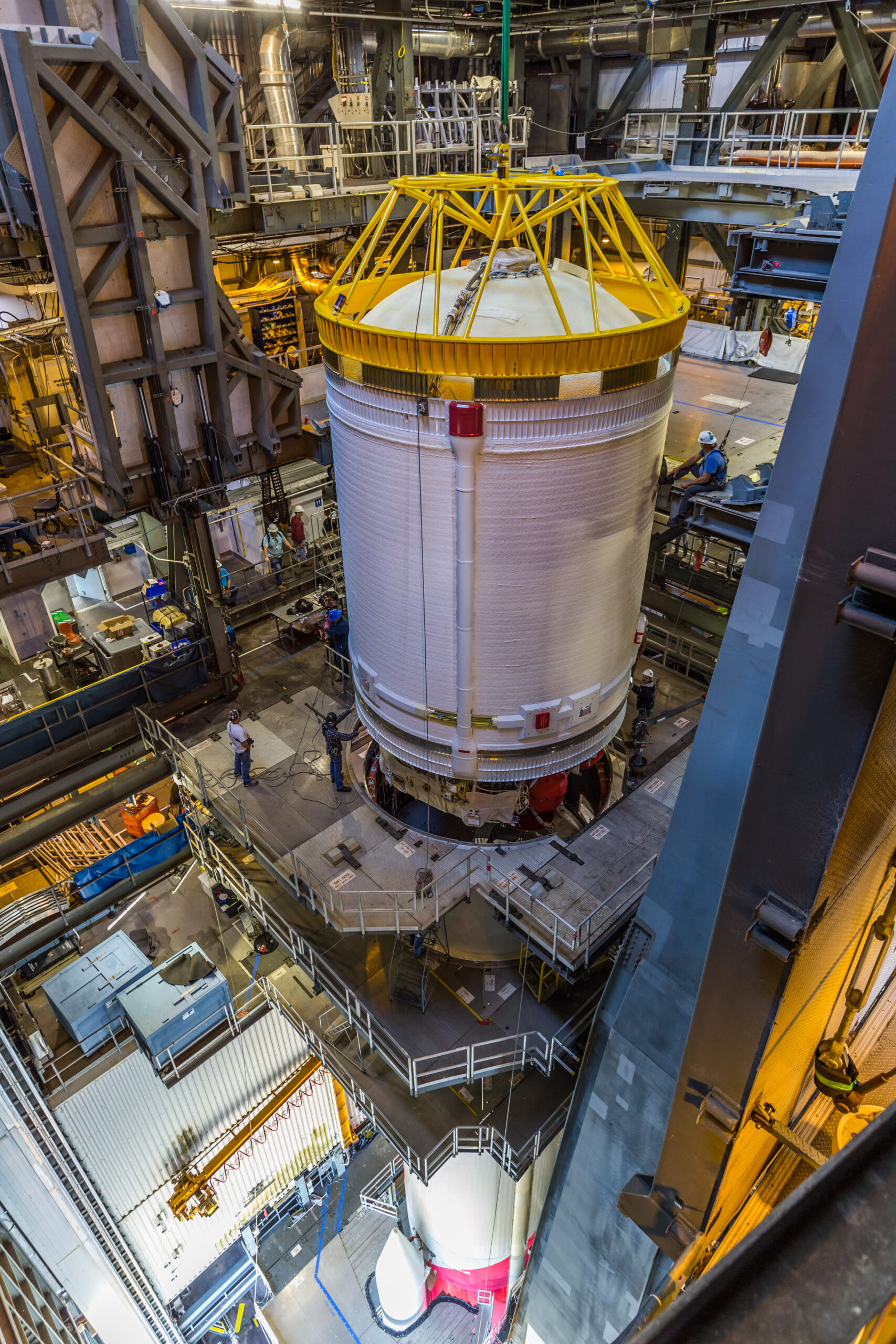

Next came the interstage adapter, with its bold U.S. flag in pride of place, followed by the 13 November arrival of the Centaur V upper stage in Florida. Six days later, the Centaur was hoisted atop the core stage in the VIF as ULA continued to target an opening launch attempt for Cert-1 at 1:49 a.m. EST on Christmas Eve.

Early on 6 December, the Vulcan-Centaur (minus its payload fairing) was rolled the quarter-mile (400-meter) distance from the VIF to the SLC-41 pad surface for an extensive Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR). This campaign saw the rocket’s systems powered up, avionics and ground hardware testing, ahead of loading about one million pounds (454,000 kilograms) of liquid methane, liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen propellants and conducting a full day-of-launch countdown from the Advanced Spaceflight Operations Center (ASOC), situated some four miles (6.4 kilometers) from the pad.

“Vehicle performed well,” tweeted ULA CEO Tory Bruno in the days after the WDR. “Ground system had a couple of (routine) issues (being corrected). Ran the timeline long so we didn’t quite finish. I’d like a full WDR before our first flight, so Xmas Eve is likely out. Next Peregrine window is 8 Jan.”

After returning briefly to the VIF, the Vulcan-Centaur was back on SLC-41 by 11 December for its second try at a full WDR. “Ground-side leaks that interfered with completing Friday’s WDR were fixed,” Mr. Bruno tweeted, as ULA teams headed towards a second WDR on the 12th.

Second-time round proved charmed. “It went great,” Mr. Bruno gushed. “The critical events we wanted to demonstrate happened nominally and on the timeline. #VulcanRocket is now in the pipe for its first launch at the next lunar window on 8 January.”

Finally, on 20 December the bullet-like payload fairing—which stands 51 feet (15.5 meters) tall and 17.7 feet (5.4 meters) in diameter—holding the encapsulated Peregrine lander and Celestis’ memorial cargo was rolled out to the VIF and attached to the top of the Vulcan-Centaur, capping-off ULA’s new rocket at 202 feet (61 meters) tall. “Now that’s what I call a tree-topper,” tweeted Mr. Bruno as stacking operations concluded.

Vulcan entered the popular consciousness a decade ago, when Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014 triggered concerns about ULA purchasing RD-180 engines from Russian manufacturer NPO Energomash to power its workhorse Atlas V. Commercial contracts with “multiple” U.S. firms to develop next-generation engines began in June 2014 and by September ULA and Blue Origin formally agreed to fund a liquid oxygen/liquefied natural gas BE-4 engine, with an expectation that it might support a Next Generation Launch System (NGLS), whose maiden flight was anticipated in 2019.

It was noted from the outset that the BE-4—two of which will power each Vulcan core stage, punching out a combined 1.1 million pounds (500,000 kilograms) of thrust at T-0—would serve to address “the need for a long-term domestic engine”. Early in the fall of 2015, production was expanded and by late 2018 Blue Origin’s engine had been formally selected to power Vulcan’s core stage.

And following a much-publicized national contest which put forward five candidate names for the rocket—Eagle, Freedom, GalaxyOne, Zeus and Vulcan, proposed by the ULA workforce, and garnering more than a million votes—the winner was picked at the 31st Space Symposium on 13 April 2015, honoring the ancient Roman god of fire.

Elsewhere, in July 2015 ULA and RUAG Space—builder of the Atlas V payload fairing components—announced a strategic partnership to establish “a U.S. composites production capability” totaling 132,000 square feet (12,000 square meters) within ULA’s 1.6-million-square-foot (150,000-square-meter) factory in Decatur, Ala. This enabled RUAG to begin fabricating payload fairings and interstage adapter components for Vulcan.

And in September 2015, ULA formed a second strategic partnership with Orbital ATK (now part of Northrop Grumman) to provide Vulcan’s strap-on GEM-63XL solid-fueled boosters, up to six of which can lift payloads up to 56,000 pounds (25,400 kilograms) into low-Earth orbit, 33,000 pounds (14,970 kilograms) to Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO) or 16,000 pounds (7,260 kilograms) directly to geostationary orbit.

Vulcan smoothly passed through its Preliminary Design Review (PDR) in the summer of 2016, yielding what Mr. Bruno called “a strong path” toward a maiden launch in 2019. But a protracted development process an inexorable move to the right.

By September 2018, Cert-1 had slipped to mid-2020 at the soonest. And with the completion of the system-level Critical Design Review (CDR) in May 2019—as Vulcan transitioned from its design phase into formal qualification—that No Earlier Than (NET) date had shifted yet again, with an expectation that it would take place “in less than two years” and no sooner than the late spring of 2021.

But that new date also continued to slip, settling on the opening half of 2023, before eventually moving into the late fall and winter. The core stage, interstage adapter and Centaur V arrived on the Space Coast last 21/22 January, all three having completed the 2,000-mile (3,200-kilometer) river-and-seagoing voyage over a little more than a week from Decatur, Ala., to the Cape, aboard ULA’s R/S RocketShip vessel.

As integrated testing got underway, Cert-1 had slipped from April 2023 to no sooner than midsummer. In the second week of March, the stack rolled a quarter-mile (400 meters) from the VIF to the SLC-41 pad surface for “tanking” tests. And last June, the core stage was put through a successful Flight Readiness Firing (FRF) of its BE-4 engines at SLC-41, allowing progress to ramp up in earnest for the most anticipated maiden launch of 2024.

A successful launch on Monday is expected to open the floodgates for several more Vulcan-Centaur missions throughout the year. Sierra Nevada Corp.’s first Dream Chaser mini-shuttle—selected by NASA as part of the second-round Commercial Resupply Services (CRS2) contract in January 2016—is expected to fly in 2024’s first half.

Last month, NASA revealed that the Dream Chaser vehicle and its Shooting Star cargo module had begun environmental, vibration and thermal vacuum chamber tests at the Neil Armstrong Test Facility in Sandusky, Ohio. Following the completion of this rigorous campaign, the spacecraft will be delivered to Florida for its launch atop a Vulcan-Centaur designated “VC4L”, equipped with four GEM-63XL solid-fueled boosters.

Additional launches penciled-in for 2024 include Vulcan-Centaur’s first launch of a Block III Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite—the 8,550-pound (3,880-kilogram) GPS III-07, named in honor of America’s first woman in space, Sally Ride—for the U.S. Space Force also slated to occur around the mid-year timeframe. And a pair of other Space Force payloads, designated USSF-87 and USSF-112, are aiming for “high-energy-orbit” Vulcan-Centaur launches at some undetermined point late in 2024.

The latter two missions were contracted with a value of $225 million to ULA back in March 2021, intended from the outset as Vulcan-Centaur payloads and originally targeting launches in the third and fourth quarters of 2023. Also scheduled to head uphill later in 2024 is the highly classified USSF-106, launch contracts for which were signed as part of a broader $337 million Space Force/ULA agreement back in August 2020.

5 Comments

Leave a Reply5 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:Vulcan-Centaur Rolls to Pad, Completes Last Major Pre-Launch Milestone - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Vulcan-Centaur Rolls to Pad, Completes Last Major Pre-Launch Milestone - SPACERFIT

Pingback:SpaceX Launches Third Mission in 2024’s First Week, ULA Vulcan-Centaur to Fly Tonight - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Maiden Vulcan-Centaur Flies, Peregrine Lander Suffers Critical Anomaly - SPACERFIT

Pingback:SpaceX Launches Third Mission in 2024’s First Week, ULA Vulcan-Centaur to Fly Tonight - SPACERFIT