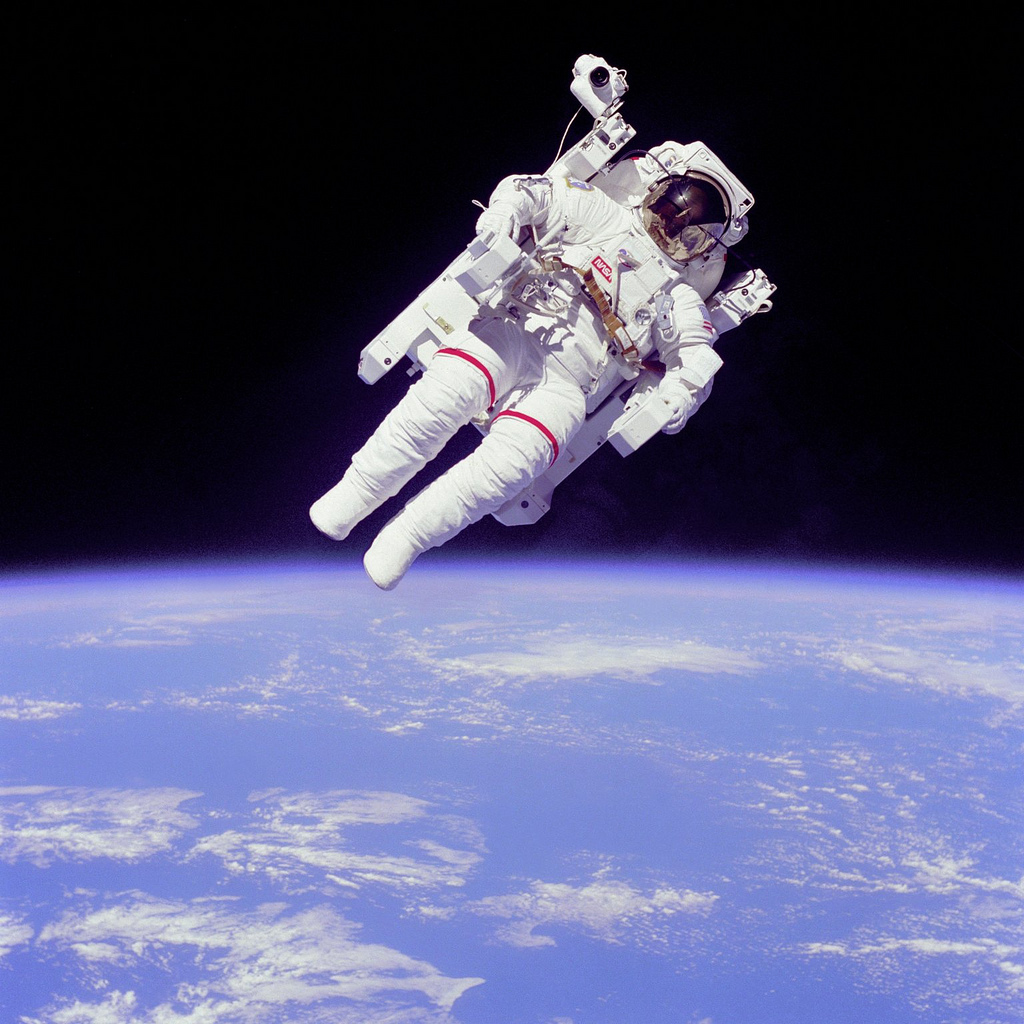

When the crew of Mission 41B—the 10th shuttle flight and the fourth voyage by orbiter Challenger—released their official patch in the fall of 1983, it included in pride of place a jet-propelled space suit backpack, known as the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), as well as the surname of an astronaut who had waited for almost two decades to fly it. Bruce McCandless joined NASA in April 1966, alongside 41B Commander Vance Brand, and one of the reasons for his long wait was the fact that he was instrumental in the design and development of the MMU, which would enable the first “untethered” spacewalk in history. Little could McCandless have envisaged that his spectacular EVAs in February 1984 would produce some of the most recognizable images of the 20th century, used time and again on spaceflight books, magazine covers, wall posters, and screensavers … and even sparking a bizarre copyright case, involving the singer Dido.

More than a decade before his spacewalks, McCandless served as backup pilot for the first manned Skylab mission and participated in the development of “Experiment M-509.” This nitrogen-fed space suit backpack was tested aboard the space station in the summer of 1973 and served as a forerunner for the MMU. “In retrospect, I probably lavished too much attention on scientific/engineering interests, as opposed to flying, flying and more flying,” McCandless told this author, years later. “At any rate, I became interested in maneuvering units shortly after the Gemini IX-A fiasco, in which Gene Cernan was overwhelmed by immature pressure suit technology and was unable to fly the U.S. Air Force Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU).”

Together with civil servant David C. Shultz and Air Force Capt. Charles “Ed” Whitsett, McCandless began work on Experiment M-509, which he described as “a multi-mode maneuvering unit,” which would be “demonstrated inside the Skylab workshop for safety and simplicity … obviating the need for expensive redundant systems and vacuum qualification.” At one stage, McCandless hoped to the first to fly it, “but that was not to be. I was named as backup pilot for Skylab 2 and waved goodbye to being on the prime crew.” Unfortunately, during Skylab’s ascent to orbit on 14 May 1973, a solar panel and the micrometeoroid shield were torn away. Temperatures inside the station soared and were only stabilized by the stoic efforts of the first crew in a complex EVA and a grueling program of emergency repairs.

“They, however, were prohibited from trying the manoeuvring unit out due to fears that its nickel cadmium batteries had been damaged by the high temperatures inside the workshop,” McCandless explained. “The two subsequent Skylab crews did use the M-509 and gave it glowing reports, thus enabling us to sell NASA management on building an MMU in connection with the shuttle, initially planned for the conduct of tile inspection and repair.” In time, the spectacular success of the jet backpack won NASA and prime contractor Martin Marietta the coveted Collier Trophy for 1984. McCandless, together with Whitsett and Martin Marietta’s Walter “Bill” Bollendonk, were granted special recognition for their contributions to its development and orbital checkout. Whitsett in particular has paid tribute to McCandless’ work. “Nobody has left his stamp on any instrument in space,” he told the Washington Post, “like Bruce has left his mark on the backpack.”

In the wake of the Columbia disaster, it seems ironic that the original purpose of the MMU was to enable spacewalking astronauts to inspect and possibly repair damaged thermal protection materials on the shuttle’s wings and lower surfaces. Moreover, in the words of a NASA news release from October 1979, it would also permit rescue operations and even the servicing of disabled satellites. Although the need to potentially repair portions of the shuttle’s thermal protection system was one of the main reasons for the MMU, its development—which began in earnest in 1975—was still hampered for some years by management apathy and lack of firm funding. Then, in the spring of 1979, as Columbia was being moved from California to Florida, several heat-resistant tiles were lost from her airframe and renewed vigour was injected into developing the backpack.

By the time STS-1 took to the skies in April 1981, most of problems had been solved and no MMU was aboard. It would instead be used, said NASA, for satellite repairs and maintenance, and its usefulness was enhanced by the provision of electrical sockets for tools, portable lights, and cameras. In June 1982, the agency announced that the shuttle would attempt to retrieve, repair and deploy the crippled Solar Maximum Mission (“Solar Max”) in the spring of 1984. Before the MMU could be committed to the repair mission, a thorough test of its performance in orbit was required and this was the task of McCandless—the MMU’s “project pilot”—and fellow astronaut Bob Stewart on Mission 41B. The pair jokingly nicknamed each other “Buck” and “Flash” during their time in space.

Physically, the MMU measured four feet (1.2 meters) high, 2.7 feet (81 cm) wide and 2.2 feet (66 cm) deep. According to astronaut Joe Allen, who flew it in November 1984, it resembled “some kind of overstuffed rocket-chair.” On a typical mission, two MMUs were stored on Flight Support Structures (FSS) on opposing walls toward the front of the payload bay. An astronaut would back into it and secure a pair of spring-loaded latches and a lap belt into place, then release the unit from its support structure and float free.

After more than four years in the design definition stage, in February 1980 NASA awarded the $26.7 million MMU fabrication contract to Martin Marietta of Denver, Colo. The first two operational flight units, valued at around $10 million apiece, arrived at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, in September 1983 to support astronaut training. Two months later, they were installed aboard Challenger. Each weighing 310 pounds (140 kg), they were painted white to achieve adequate thermal control in the harsh environment of low-Earth orbit and were fitted with electrical heaters to keep their components above minimum temperature levels.

Affixed to the back of each MMU were two propellant tanks, which supplied 24 tiny thrusters with a total of 40 pounds (18 kg) of high-pressure gaseous nitrogen. To operate the thrusters, the astronaut used hand controllers at the end of two armrests: one provided roll, pitch, and yaw control, whilst the other allowed him to move forward, backwards, up, down, and from left to right. Furthermore, by using both in unison, he could achieve very intricate movements. Particularly useful for repair missions, when a desired orientation had been reached, he could activate an automatic, “attitude-hold” function to free his hands for work. Electrical power came from a pair of silver zinc batteries, capable of supporting the unit for up to six hours of autonomous flight as far as 460 feet (140 meters) from the shuttle.

In fact, one of the MMU’s widely publicized features was that its wearer did not need to remain attached to the spacecraft by a safety tether. Of course, in the event of problems, most of its systems were redundant and neither McCandless or Stewart would venture so far from Challenger that the pilots would not be able to rescue them if necessary. According to the Mission 41B Press Kit, their actions would be conservative. “Both McCandless and Stewart will fly untethered from Challenger to distances of about 150 feet (50 meters),” it was noted, “then to 300 feet (100 meters) and return.”

Quipped Commander Vance Brand: “We didn’t want to come back and face their wives if we lost either one of them up there!”

The MMU’s controllability was crisp and precise. “The minimal training and precision flying features,” said one observer, who flew a model of the MMU at Martin Marietta’s Space Operations Simulator (SOS) in Denver, “were demonstrated by my ability, with only a few minutes’ practice, to maneuver safely in close proximity to fixed objects.” Joe Allen, whose own MMU sortie salvaged an errant communications satellite, also remarked that in space it “glided” and displayed none of the idiosyncratic jerks, jolts, bumps, and grinding sounds that were characteristic of Martin Marietta’s simulator.

For Bruce McCandless, who backed himself into the device early on 7 February 1984, it represented “a heck of a big leap,” in terms of spacewalking technology and the culmination of his own personal odyssey. Preparations for this excursion had begun soon after Challenger reached orbit, four days earlier. The shuttle’s cabin pressure was lowered from 101.3 kPa (“normal” atmospheric pressure at sea level) to 70.3 kPa in order to reduce McCandless and Stewart’s “pre-breathing” routine from three hours to less than one hour.

It was familiar ground for McCandless, who admitted to this author in a 2006 email correspondence that he was “probably not a representative EVA trainee” and had been “grossly over-trained.” Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, he took every opportunity to get into a space suit, an altitude chamber, or a water tank, and in addition to his work developing Experiment M-509 and the MMU, he had also participated extensively in EVA simulations on Skylab and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). At Martin Marietta’s Denver facility, he and Stewart had “flown” mockups of the MMU within the SOS, which measured 50 feet (15 meters) long by 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) wide and 14.8 feet (4.5 meters) high. “It was quite effective,” McCandless concluded, “and could accommodate a fully-suited astronaut and reasonable sized mockups of ‘target’ objects, such as the underside of the orbiter for tile repair. It also had the capability for introducing malfunctions for training purposes.”

In spite of their complexity, McCandless and Stewart’s excursions proved successful and the space suits and MMUs performed admirably. The only “nuisances” were static on the communication channels and difficulties attaching checklists to the suits’ arms. “In spite of the sound-does-not-travel-through-a-vacuum tenet of physics,” McCandless remembered, “it was noisy up there, thanks to two independent radio channels and plenty of people wanting to talk to me!” Then, just before leaving Challenger’s airlock, Stewart reported a caution and warning alarm, which indicated the pressure of his suit’s sublimator had risen to 27.6 kPa. However, after being switched off and back on again, it performed normally.

These subtle problems did not distract from the triumph of McCandless’ Buck Rogers-style flight that day. Despite the sci-fi analogy, said Vance Brand, the MMU “didn’t have the person zooming real fast. It was a huge device that was very well-designed and redundant, so that it was very safe, but it moved along at about one to two miles per hour.” At his furthest distance from the shuttle, McCandless was almost 300 feet (91 meters) away, politely offering to clean Challenger’s cockpit windows as he floated over the flight deck. Watching intently from inside, an admiring Brand declined the offer.

Also watching intently, camera in hand, was Robert “Hoot” Gibson, Challenger’s pilot, and the person who snapped the photograph which would make history as one of the top five most-requested images from NASA. In an interview for the Smithsonian in 2001, he recalled the astonishing sight of McCandless flying the MMU. “Bruce first did a couple of brief test flights in the cargo bay, staying very close in case anything should go wrong,” Gibson explained. “As we were approaching sunrise on one of our daylight passes, he was cleared to make the translation out to 300 feet from the shuttle.”

Grabbing his Hasselblad camera, Gibson began shooting frame after frame. Since Challenger’s orientation was some 30 degrees from the vertical, McCandless appeared at a similar angle with respect to Earth’s horizon. Gibson knew that any one of his images could easily make the cover of Aviation Week—they actually made two—and remembered taking multiple light settings and tweaking the focus five or six times for each photograph, before squeezing the button.

The famous shot would come to be known as “Backpacking,” and, even today, McCandless possesses a goofy version in his home, in which his grown daughter pokes her head through the cut-out visor in a life-size reproduction at a Seattle, Wash., museum. In 2005, McCandless explained that what he liked most about the image was its lack of identity; with his sun visor closed, it is impossible to see his face, “and that means it could be anybody out there … sort of a representation, not of Bruce McCandless, but mankind.” This assertion gained a measure of irony a few years later, when, in the fall of 2010, he sued the singer Dido for her unauthorized use of the image on the cover of her album, “Safe Trip Home.” Although NASA images are not bound by copyright, McCandless argued that the image infringed his “persona,” but the case was settled amicably early the following year.

This is part of a series of articles to commemorate 50 years of U.S. Extravehicular Activity. Tomorrow’s article will focus on the EVAs of the first Hubble Space Telescope (HST) Servicing Mission, which not only brought the iconic observatory back from the brink of failure, but enabled many of NASA’s future explorations in space.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » US EVAs »

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:‘For Tasks That Might or Might Not Take Place’: 30 Years Since Atlantis’ Maiden Voyage (Part 1) « AmericaSpace