On 116 occasions in the past 15 years, white-suited spacewalkers from the United States, France, Russia, Germany, Sweden, Canada, Japan, Italy, and the United Kingdom have departed a stubby, two-chambered module on the starboard side of the International Space Station (ISS) and made important contributions to its assembly, maintenance, and repair. From the inaugural departure of STS-104 astronauts Mike Gernhardt and Jim Reilly for four hours and two minutes on the night of 20/21 July 2001 to the return of Expedition 46 crewmen Tim Kopra and Tim Peake after four hours and 43 minutes on 15 January 2016, dozens of spacewalkers have entered and exited the Quest airlock. And when Quest arrived at the space station all those years ago, it could hardly have been anticipated how pivotal a role it would play in the future.

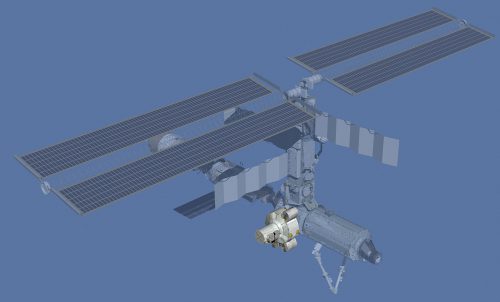

Measuring 18 feet (5.5 meters) in length and 13 feet (4 meters) in diameter at its widest point, Quest was originally known as the “Joint Airlock” and was born in the mid-1990s when Space Station Freedom evolved—through an extensive remodeling of the multi-billion-dollar program—into the kernel of today’s ISS. Built by the station’s prime contractor, Boeing, it comprised two segments: an inner “equipment lock,” in which Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) space suits and tools could be stored, and an outer “crew lock,” for the actual departure of personnel into space. Quest also accommodated attachments for a quartet of high-pressure gas tanks of oxygen and nitrogen for atmospheric replenishment of the U.S. Orbital Segment (USOS) of the station.

In June 1997, NASA astronauts Mike Gernhardt—himself a veteran spacewalker—and Jim Reilly were assigned to begin long-range training for shuttle mission STS-100, then planned to deliver the Joint Airlock to the station no sooner than August 1999. For Gernhardt, a professional deep-sea diver before he became an astronaut, the installation of the new module was critical. And one of the most critical objectives was attaching the high-pressure gas tanks. “Our flight was considered one of the highest-risk assembly flights in the initial assembly sequence because of these high-mass, high-pressure gas tank [Orbital Replacement Units],” he told a NASA interviewer before the flight.

Their installation was originally planned to be a robotics task, but was later moved to an EVA task. Gernhardt was keenly aware that the tanks were 2.5 times larger than even the largest ORUs which had been fitted to the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). Shortly after his assignment, he approached the Boeing engineers and told them that the success of the mission would hinge upon the techniques used to handle the huge tanks. Over the next few years, mockups of the tanks were fabricated and Gernhardt and Reilly spent many hours underwater in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, evaluating tools and methods. In time, Gernhardt would come to realize that the lengthy delays which his mission incurred proved beneficial. “Without that lead time,” he said, “we might’ve been stuck with something that would’ve been an uphill battle.”

Although Quest’s rise to space was originally targeted for August 1999, delays to the fledgling ISS program—and specifically the Russian-built Zvezda (“Star”) service module—forced the assembly sequence to shift slowly but surely to the right. In fact, by August 1999, the launch of Zvezda was still nearly a year away and it needed to be in place before five key shuttle assembly missions could even take place. And when they had taken place, assuming no delays, the turn would come for Quest. At length, Zvezda rocketed into orbit in July 2000 and shuttle construction resumed in earnest. Later that fall, Gernhardt and Reilly were joined by Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Charlie Hobaugh, and Mission Specialist Janet Kavandi on a flight which had now been redesignated “STS-104.” It was tentatively scheduled for launch in May 2001, but slipped into June and, eventually, into July.

Loaded into the payload bay of shuttle Atlantis, Quest finally rose into space at 5:04 a.m. EDT on 12 July, kicking off what was expected to be an 11-day mission with at least three spacewalks by Gernhardt and Reilly. Over the course of the first 48 hours of the flight, Lindsey—the youngest person ever to command a shuttle mission to the ISS—and Hobaugh pulsed Atlantis’ thrusters to position themselves for a rendezvous and docking late on 13 July, whilst Kavandi oversaw the early checkout of the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm. Meanwhile, Gernhardt and Reilly worked in the shuttle’s middeck to power up and test their EMUs and noticed a potassium hydroxide leakage from one of the batteries in the third (backup) suit. They cleaned it up and swapped out the battery without incident.

Early on the evening of the 13th, Lindsey executed the Terminal Initiation (TI) burn as Atlantis approached within 50,000 feet (15,240 meters) of the ISS and subsequently assumed manual control of his ship and guided it to about 600 feet (180 meters) “below” the station. He followed a quarter-circle profile around his quarry and brought Atlantis to a point about 300 feet (90 meters) from Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2 at the forward end of the U.S. Destiny laboratory. Upon receiving a go-ahead from U.S. and Russian flight controllers, he proceeded with the rendezvous and completed a smooth docking at 11:08 p.m. EDT, some 42 hours after launch. At the point of contact between the two vehicles, they were orbiting about 240 miles (380 km) above the northeastern coast of South America.

Less than two hours later, hatches between the shuttle and the ISS were opened and Lindsey, Hobaugh, Gernhardt, Kavandi, and Reilly floated aboard the station to be welcomed by the incumbent Expedition 2 crew of Commander Yuri Usachev and Flight Engineers Jim Voss and Susan Helms. There was precious little time for celebration, for Gernhardt and Reilly’s first EVA was scheduled to begin late on Saturday night. In readiness, Atlantis’ RMS and the station’s newly-arrived Canadarm2 were put through a “dry run” of how they would remove Quest from the payload bay and bring it up to its permanent home on the starboard side of the Unity node. On the shuttle side, Janet Kavandi handled RMS operations, whilst station-side operations were overseen by Susan Helms.

Early on Saturday morning, 14 July, the hatches between the two spacecraft were closed as Atlantis’ cabin pressure was lowered from 14.7 psi to 10.2 psi in anticipation of EVA-1. Gernhardt (designated “EV1,” with red stripes on the legs of his suit for identification) and Reilly (“EV2,” clad in a pure white ensemble) departed the shuttle’s airlock at 11:10 p.m. EDT, their every move choreographed by Charlie Hobaugh. Getting straight down to business on the second spacewalk of his career, Gernhardt removed an insulating cover—nicknamed the “shower cap”—from Quest’s berthing mechanism, whilst Reilly set about installing the “towel bars” for attaching the high-pressure gas tanks.

About an hour into the EVA, Helms grappled Quest with Canadarm2 and extracted the 13,370-pound (6,000-kg) airlock from Atlantis’ payload bay. She maneuvered it to its attachment location at the starboard Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM) of the Unity node, where Gernhardt and Reilly waited and watched. The slow and intricate process was complete by 3:40 a.m. EDT on 15 July, whereupon the spacewalkers attached cables from the station to the airlock to provide heating and power. They then returned to the shuttle’s own airlock, wrapping up EVA-1 after just a minute shy of six full hours.

With the second spacewalk planned for three days later, the joint crews focused their attention on outfitting the new module. The six men and two women worked to test nitrogen and oxygen lines and installed valves which integrated Quest into the space station’s Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS). Lindsey and Usachev, the respective commanders of STS-104 and Expedition 2, also cut a ceremonial white ribbon across the entrance to the crew lock. In spite of air bubbles and a water spillage from a coolant line, these efforts ran smoothly and Usachev, Voss, and Helms successfully trialed the airlock’s audio communications system, making the first radio calls to Mission Control from Quest. Later, the new module’s internal pressure was lowered to 10.2 psi, providing a dry run for the conditions needed by Gernhardt and Reilly when they performed the first-ever Quest-based EVA, later in the mission.

However, the water spillage and a leaky ventilation valve had placed the STS-104 crew about a half-day behind schedule, forcing a number of tasks to be deferred. The Mission Management Team (MMT) also elected to add an extra day of docked operations to the flight and pushed EVA-3 back by 24 hours from its original place on the evening of 19 July to the evening of 20 July. In the meantime, on the 17th, efforts to prepare for the second spacewalk entered high gear. In a fashion not dissimilar to EVA-1, the hatches between Atlantis and the station were closed several hours before the spacewalk and the shuttle’s cabin pressure was reduced to 10.2 psi. The day also marked Kavandi’s 42nd birthday and the STS-104 crew was awakened to the strains of “Happy Birthday, Darlin’” by Conway Twitty.

The second EVA was slightly delayed when the space station’s primary command and control computer—which would guide Canadarm2 as it maneuvered the high-pressure gas tanks from Atlantis’ payload bay to their eventual location on Quest—hiccuped and had to be restarted. At length, Gernhardt and Reilly entered the shuttle’s floodlit payload bay at 11:04 p.m. EDT and moved smartly through their tasks. Original plans called for two of the four tanks (one of oxygen, the other nitrogen) to be installed on EVA-2, but the spacewalkers latched them into place without difficulty and Flight Directors Paul Hill and Mark Kirasich elected to push ahead with attaching a third (oxygen) tank. The second spacewalk of STS-104 ended at 5:33 a.m. EDT on 18 July, after six hours and 29 minutes.

With two days remaining before EVA-3, additional time was afforded to the joint crews to replace a leaky valve in an Intermodule Ventilation (IMV) Assembly inside Unity. The replacement was done by Lindsey and Voss, whilst their crewmates continued with the activation of the airlock and transferred tools and equipment for EVA-3. The hatch between the inner equipment lock and the outer crew lock was installed and leak-checked over a period of several hours.

Finally, on the evening of 20 July 2001—exactly 32 years since humanity took its first steps on another heavenly body—all was ready for what NASA expected would allow the space station to really come into its own, as Gernhardt and Reilly prepared for the first EVA from Quest. Across two phases, the United States, Russia, and their partners had moved through the shuttle-Mir program and assembled the early hardware of the ISS. And with STS-104 and the activation of Quest, Phase Two was complete. This allowed what NASA described as “a higher degree of station independence in its own construction and maintenance.” From the moment Gernhardt and Reilly pushed open the crew lock’s hatch on 20 July to the instant Expedition 46 spacewalkers Tim Kopra and Tim Peake closed it on 15 January 2016, Quest would quite literally provide nothing less than a doorway to space.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » ISS » Missions » US EVAs »

4 Comments

4 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:Oldest U.S. Spacewalker Set to Lead Commercial Crew EVA on Friday « AmericaSpace

Pingback:Space Station Open for Commercial Crew, As EVA-36 Team Installs IDA-2 « AmericaSpace

Pingback:‘To Train a Mission’: 15 Years Since STS-105 (Part 1) « AmericaSpace

Pingback:‘Easier to Destroy Than Create’: 15 Years Since STS-105 (Part 2) « AmericaSpace