More than 30 years ago, the 13th flight of the shuttle program roared into orbit. Aboard Challenger for Mission 41C were Commander Bob Crippen, Pilot Dick Scobee, and Mission Specialists Terry Hart, James “Ox” van Hoften, and George “Pinky” Nelson, tasked with the deployment of NASA’s Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) and the retrieval, EVA repair, and return to space of the crippled Solar Maximum Mission, also known as “Solar Max.” Launched on St. Valentine’s Day in 1980, the 5,100-pound (2,315-kg) Solar Max suffered a major electronics failure within months, potentially ruining its mission to explore the mechanisms responsible for causing solar flares. Fortunately, it had been designed as a Multi-Mission Modular Spacecraft (MMS), capable of being serviced by the shuttle, and in August 1982 NASA approved a rescue flight to revive Solar Max. That rescue flight—which utilized the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) jet-propelled backpack and extensive Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm operations—would turn into one of the most spectacular missions of the 30-year shuttle era.

The crew was announced in the spring of 1983, targeted for launch in April 1984, and it was clear that Mission 41C was a plum assignment. “This was the mission I wanted,” said Nelson, “because it had EVAs. I remember meeting with Crippen shortly after that, in one of the little conference rooms, where he doled out the assignments and gave me the role of flying the MMU, which made my year! Here was a mission with four military pilots and they decided to let me fly the maneuvering unit. Training for that mission was really fun. It was really the most complicated spacewalk that had ever been conceived and a real precursor to the much more complicated work they’ve done on the Hubble Space Telescope. We worked hard to choreograph this repair and we had it down to a dance. We knew all the steps and who was where when, what tools were needed and how we moved things.”

At first, it seemed likely that Hart would join Nelson on the EVAs, because the word on the astronaut grapevine was that van Hoften—the biggest member of the crew—was too large to fit the space suits. Nevertheless, one day, Crippen told Hart that his expertise was better suited to the RMS operation and that Nelson and van Hoften would perform the spacewalks. “About that time,” van Hoften explained, years later, “[NASA] started running into money crunches and they said that they wanted to limit the space suit sizes, because originally the [space suit] that they made was meant for everybody. It was supposed to be from the 5th percentile female to the 99th percentile male. Well, I was the biggest guy they ever had, so at some point they decided they weren’t going to make extra-large suits anymore; they were just going to make small, medium and large, and those of us on the fringes weren’t going to get to do it.” It was a disappointment, but van Hoften still had a spot on what he described as “one of the premier missions.” At length, it was George Abbey, then-head of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate (FCOD), who came to the rescue, insisting that van Hoften should do the EVAs and ordering that a pair of extra-large suits be manufactured.

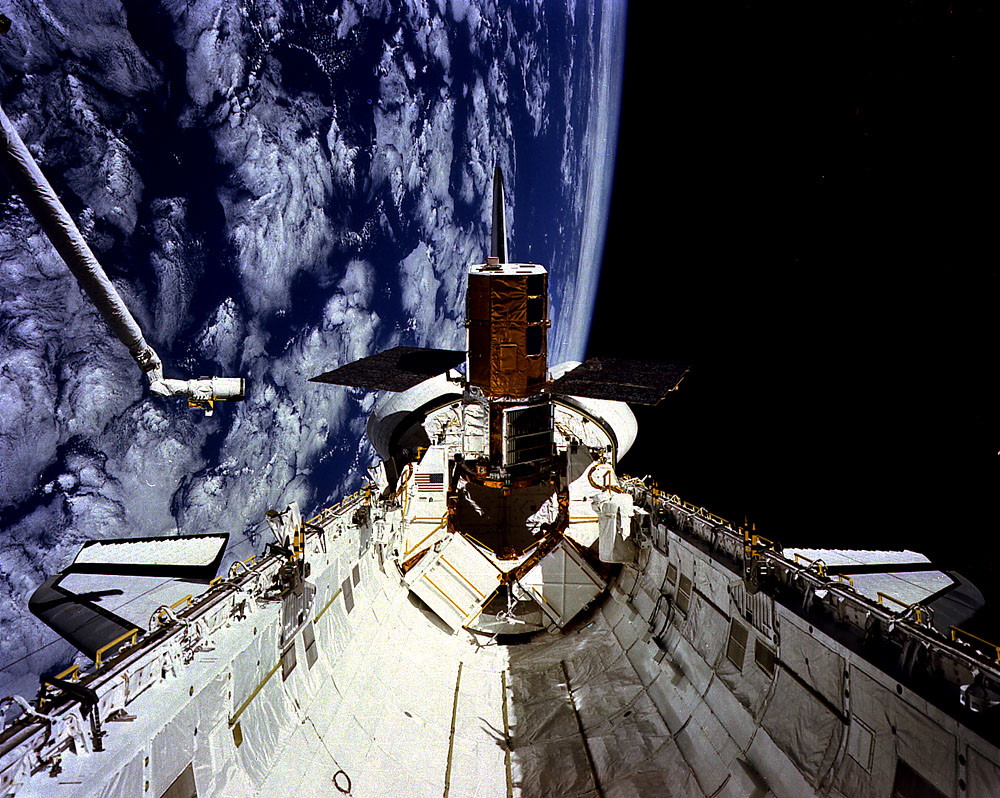

For 14 months, the crew trained exhaustively for a repair mission like nothing previously attempted in the history of the U.S. human space program. At length, Challenger rocketed into orbit on 6 April 1984, and, after deploying LDEF, they completed a smooth rendezvous with Solar Max on the morning of the 8th. Crippen positioned the orbiter about 230 feet (70 meters) from the slowly spinning satellite, as Nelson and van Hoften finished donning their space suits in the airlock and entered the payload bay at 9:18 a.m. EDT. “There’s no comparison to getting into a suit and being outside,” van Hoften later told the NASA oral historian. “It was just a whole new world. You open the hatch and you look out and there goes Africa! It’s just so distracting that it took probably 20 minutes until you start saying, ‘Hey, we’ve gotta get back on track here’.” But it was just amazing. We had done so much work in the water tank, but in zero gravity it’s really a lot different.” The plan was for Nelson, designated “EV1,” to fly the MMU out to the satellite and dock to its mid-section using a Trunnion Pin Attachment Device (TPAD).

Although Solar Max was not spinning too fast for Hart to grapple it with the RMS, “we felt it was more prudent to have Pinky fly over with a backpack, dock himself to the satellite, stabilize it and then I could grab it with the arm.” Precisely on time, after a 10-minute solo flight, Nelson arrived in Solar Max’s vicinity and used the MMU’s thrusters to gently match its rotation. Unfortunately, when he moved in to mate his TPAD with the satellite, it did not clamp properly into place. “We didn’t know what was wrong,” explained Hart, “but, being mechanical engineers, we said ‘If a small hammer doesn’t work, use a bigger hammer!’ So Pinky went in twice as fast the next time and he hit again and bounced right off again.”

A third try, which imparted yet more force, also failed.

Had the TPAD been affected by the cold of orbital darkness? Its temperature after removal from the payload bay storage locker had not been maintained, but pre-flight tests and actual flight experience on Mission 41B determined it was capable of withstanding at least a few hours in the frigid darkness. Low temperatures did not seem to be a contributory factor. Furthermore, when Nelson pushed the TPAD against Solar Max, its trigger activated and released a pair of jaws in an attempt to grab onto its quarry. This ruled out a malfunction in the docking hardware. However, as the first EVA continued, the crew noticed another problem: Nelson’s efforts had jostled Solar Max out of its slow spin, and Crippen asked him to grab a solar panel to steady it. The gyroscopic effect of this action worsened matters, and, with his MMU’s nitrogen supply running low, Nelson returned to Challenger. Instead of revolving gently, Solar Max was now tumbling around all three axes.

Four tries by Hart to grapple it with the RMS proved fruitless, and Crippen opted to withdraw to a distance of about 100 miles (160 km) until a new strategy could be thrashed out. “The grappling pin I had to grab was underneath one of the large solar panels, so I could only get there under certain conditions,” recalled Hart, “and it was very hard to predict how it was doing. I got close to it and I was maybe a foot away from getting it, but I’d reach some limit on the elbow or the wrist. I couldn’t go far enough or fast enough to get it. It may be a good thing, because the satellite was tumbling so much that if I had gotten it, it may have actually broken the arm! Crippen, rightfully, said ‘King’s X. Let’s go back’. We got the shuttle back in position in front of the satellite and then we stabilized everything. We had fuel left, but not enough to do what we were doing anymore.”

Privately, the astronauts were convinced that they had blown it and that the mission was a failure. “I could see myself spending the next six months in Washington,” Crippen told the NASA oral historian, “explaining why we didn’t grab that satellite!”

Overnight, as the astronauts slept, engineers at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., which operated the satellite, battled to regain control, but since its solar panels were no longer pointing toward the Sun, battery power was gradually dwindling away without recharging. The engineers switched off as many systems as possible, including heaters, but still had only six to eight hours of battery life left. When it became clear that Solar Max’s magnetic torque bars were now slowing the rotation, Goddard implemented a new technique, using a different method of sensing its position. This made the bars more effective in “pushing off” against Earth’s magnetic field, and the satellite quickly stabilized itself. Then, just as battery life was running out, it came around in its orbit in such a way that the electricity-generating panels faced sunward once more and began to recharge. When the crew awoke on the morning of 9 April 1984, the satellite’s batteries were powered and it was rotating serenely at half a degree per second.

“Then we talked about what we had to do and Mission Control worked out the available fuel,” said Terry Hart in a NASA oral history interview, “but we took an extra day and decided we would do a second rendezvous. This time, Pinky and Ox would stay inside the orbiter and I would try to capture it with the arm.” It also became clear during the second spacewalk precisely why Nelson’s attempts to capture Solar Max had been three times frustrated: a small grommet, just 0.8 inches (20 mm) high and 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) thick, had obstructed the full penetration of the TPAD onto the satellite’s trunnion pin. The grommet, which was installed near the pin, helped to hold part of Solar Max’s gold-colored thermal insulation blanket in place.

“What no-one noticed,” explained Hart, “is that one of the blankets had been put on with a little fiberglass standoff that the grommets would fit over. The engineering drawings didn’t specify where those standoffs could be, so when they assembled the satellite, the technicians just put one wherever the grommet was. They glued it onto the metal frame, then stuck the blanket on. That was the correct thing to do, because no-one envisioned using that pin for anything.” A use for the pin did emerge, a year after Solar Max’s launch, when the option of a shuttle repair was first explored in depth. “But when they were designing the TPAD,” Hart continued, “no-one noticed that there was a grommet there. When Pinky went to dock, it interfered with the docking adapter.”

It turned out that, if Nelson had made his approach to the pin within a very narrow pitch angle “corridor,” he might have succeeded and captured Solar Max. However, during his second EVA, he took measurements of where the grommet was and the obstruction it posed, and found that it stuck out 0.6 inches (1.5 cm) too far. The TPAD, clearly, would not work. Either way, Challenger’s on-board fuel was now too low to support a rescue if Nelson’s MMU happened to fail. Instead, Crippen would fly close enough to Solar Max for Hart to grapple it with the mechanical arm.

Early on 10 April, on his first attempt, Hart successfully grappled Solar Max with the RMS and anchored it onto a Flight Support Structure (FSS) at the rear end of the payload bay. “It was a dramatic moment for Mission Control,” he remembered later. “We were euphoric when we succeeded. We really felt that the mission was at risk, which it was, and we were really on a mission that was demonstrating the flexibility and usefulness of the shuttle to do things like repair.”

The spectacular success, sadly, would prove to be the MMU’s death knell.

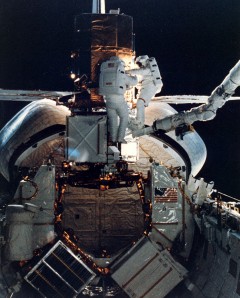

An umbilical line was connected to the satellite to feed it with power from the orbiter, and it was pivoted around so that Nelson and van Hoften, during their second spacewalk, which began at 3:58 a.m. EDT on 11 April, could reach and fix its broken attitude control system and the main electronics box of its disabled coronagraph and polarimeter. These repairs were originally meant to occupy one EVA apiece, but with the condensed and rescheduled flight plan it was decided to attempt both during the same excursion. Replacement of the attitude control box, which had been responsible for crippling the $240 million project more than three years earlier, took just 45 minutes.

Standing on the end of the RMS, his feet anchored in restraints, van Hoften removed a pair of screws, pulled the box out smoothly, and plugged in a new unit. The second procedure of fixing the main electronics box to the coronagraph and polarimeter, which was not designed for replacement in orbit, was expected to be a longer and trickier task. Nonetheless, with surprising dexterity and outstanding skill, van Hoften pulled back a panel covering the box, cut and taped back a layer of insulation, removed two dozen screws, and cut several wires. Nelson then took over, installing the new electronics box using large, gold-plated beryllium clips, instead of tiny screws, for the connectors. An hour after their second task had begun, they were finished and were able to place a baffle cover over the X-ray polychromator to vent its exhaust gases away from Solar Max’s other instruments.

The second EVA had lasted six hours and 44 minutes, which, together with their 2.5-hour outing on 8 April, brought Nelson and van Hoften’s spacewalking time to more than nine hours. “The repair itself was a kick,” Pinky Nelson recalled years later. “It was so much easier to work in space than it is on the ground. Ox and I, and T.J. Hart running the arm, just kind of did this repair. It was a piece of cake! It was so much fun riding on the end of the arm and much easier than working underwater.” The pilots, too, were just as excited, particularly Scobee, who persuaded his crewmates to don T-shirts for the space-to-ground press conferences, emblazoned with the legend, Ace Satellite Repair Company.

Finally, after a day of checkout in the payload bay, on 12 April 1984 Hart grappled the satellite with the RMS and deployed it back into space. After a four-week checkout, Solar Max resumed work on what would turn into more than five years of observations of changes in the Sun’s energy output. Its coronagraph and polarimeter, repaired by Nelson and van Hoften, resumed work in June 1984 and, despite a few interruptions, continued to capture images of the solar corona during the “daytime” portions of the satellite’s orbit until the end of the mission in the fall of 1989.

If Mission 41C—the 13th shuttle mission—was stricken with bad luck at all, the greatest victim must have been the MMU jet backpack, first tested by Bruce McCandless two months earlier. Admittedly, it had performed admirably and could hardly be blamed directly for the failure of the TPAD. Indeed, it would prove its worth in November 1984 when, flown by Joe Allen and Dale Gardner, it was instrumental in the retrieval of the errant Palapa-B2 and Westar-VI communications satellites.

However, what Mission 41C did prove was the crisp maneuverability of the orbiter itself and the precise handling characteristics of the RMS. It was, observers said later, Hart’s small grab, rather than Nelson’s free flight, which had pulled success from the jaws of what might have been an ignominious defeat. Yet that is to underestimate the importance of EVA, for the spacewalks conducted by Nelson and van Hoften were a factor of complexity beyond anything previously accomplished in U.S. human spaceflight history and their lessons would go a long way toward planning the spacewalks which would one day service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and the International Space Station (ISS).

This is part of a series of articles to commemorate 50 years of U.S. Extravehicular Activity. Tomorrow’s article will focus on the final flight of the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) in November 1984, which triumphantly captured two stranded communications satellites and brought them back to Earth.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » US EVAs »