Within the last month, NASA’s two Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) partners have delivered their respective cargo ships to the International Space Station (ISS), marking the first occasion that both have been represented simultaneously aboard the orbital outpost. Orbital ATK successfully berthed its OA-6 Cygnus vehicle on 26 March, whilst SpaceX returned to the station after almost a year-long hiatus with last weekend’s spectacular voyage of the CRS-8 Dragon. Both vehicles are now firmly attached to the U.S. Orbital Segment (USOS), with Cygnus at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) interface of the Unity node and Dragon at the nadir port of the Harmony node. This has served to boost the ISS population of piloted and unpiloted visiting vehicles to as many as six for the first time in its history.

A key player in enabling the berthing of both Cygnus and Dragon, as well as Japan’s H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV), and supporting myriad robotic operations over the years has been Canada’s contribution to the space station program: the 57.7-foot-long (17.6-meter) Canadarm2. Launched 15 years ago, in April 2001, the “Big Arm” is an evolution of the Space Shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS). Between its first voyage on Columbia’s STS-2 mission in November 1981 and the final swansong of the shuttle program on STS-135 in July 2011, the six-degrees-of-freedom RMS provided the means and the muscle to retrieve and repair numerous Earth-circling spacecraft—including Solar Max, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), and several commercial communications satellites—and deploy a variety of others, such as the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO), the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), and the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA). And for the first couple of years of ISS assembly, the RMS played a central and pivotal role.

Then came Canadarm2.

Ever since President Ronald Reagan initially proposed a U.S.-led “international” space station in his January 1984 State of the Union address, Canada was a staunch supporter and participant, through its Mobile Servicing Center (MSC) for robotic assembly and maintenance. The station was named “Freedom” in June 1988 and subsequently evolved through several design incarnations, as well as a painful redesign process, before drawing in Russian partnership and experiencing a rebirth as the ISS. By the middle of 1997, less than a year ahead of the scheduled start of construction, Canadarm2—officially designated the Space Station Remote Manipulator System (SSRMS)—was baselined for ISS Assembly Mission 6A, the sixth dedicated shuttle construction flight, then planned for a June 1999 launch aboard Atlantis. Unlike the RMS, the Big Arm had seven degrees of freedom and, through the presence of two “wrists” and two “hands,” carried the ability to “inchworm” along the ISS structure by means of interfacing with Power and Data Grapple Fixtures (PDGFs). This gave it a far greater reach than its shuttle counterpart.

In anticipation for this and other EVA- and robotics-heavy missions, a cadre of spacewalkers were announced by NASA in June 1997. Assigned to 6A were Chris Hadfield, who would become Canada’s first spacewalker, together with NASA’s Bob Curbeam. During two planned EVAs, Hadfield and Curbeam were tasked with outfitting the newly-arrived U.S. laboratory module and installing the 3,970-pound (1,800-kg) Canadarm2. “It was the world’s most expensive and sophisticated construction tool, and getting it up and running would require not one EVA, but two,” wrote Hadfield in his memoir, An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth. “And I was EV1, lead spacewalker, though I’d never been outside a spaceship in my life.” Comparing spacewalking to rock-climbing, weightlifting, repairing a small engine, and performing an intricate pas de deux—simultaneously—Hadfield soon recognized that each of the two EVAs needed to be carefully choreographed by hundreds of people. “Hyper-planning is necessary because any EVA is dangerous,” he wrote. “You’re venturing out into a vacuum that is entirely hostile to life. If you get into trouble, you can’t just hightail it back inside the spaceship.” For the next two years, Hadfield and Curbeam worked to develop their two EVAs and became a close-knit team.

At the same time, delays to the ISS construction effort caused 6A and several other missions to slip to the right, eventually until mid-2000 at the soonest. And in September 1999—following the removal of veteran NASA spacewalker Mark Lee from STS-98—Curbeam was shifted into his former spot and seasoned shuttle astronaut Scott Parazynski was moved up to join Hadfield on 6A. Finally, as ISS assembly resumed after two years of delays, the mission received the remainder of its crew. By this stage, 6A’s objectives had expanded to include the second flight of the Italian-built Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM), and, in February 2000, Italian astronaut Umberto Guidoni was assigned to join Hadfield and Parazynski. Rounding out the seven-strong crew, in September 2000, NASA named astronauts Jeff Ashby and John Phillips and Russian cosmonaut Yuri Lonchakov, commanded by four-time shuttle veteran Kent Rominger.

With U.S., Russian, Italian, and Canadian astronauts and cosmonauts, this made STS-100 the most diverse international crew ever to have flown aboard the shuttle at that time. Four discrete nations represented on one mission neatly eclipsed the previous record of three nations, which had been achieved on several previous shuttle flights. STS-51G in June 1985 counted citizens of the United States, France, and Saudi Arabia on its crew, whilst a number of post-Challenger missions also boasted representatives of three nations. “Its members represent more nations than has any other single crew,” noted NASA’s press kit for STS-100. “Once aboard the station, four out of five of the project’s major partners will be represented, the most that have ever been aboard the complex together.”

By this stage 6A had shifted to Shuttle Endeavour and the mission designator of STS-100—“Nice, round number,” according to Hadfield in a pre-flight NASA interview—had moved to no earlier than April 2001. Despite its designation, STS-100 had fallen at such a point in the manifest that it was actually the 104th shuttle mission. Liftoff of what Rominger described as “an aggressive flight” took place on-time at 2:41 p.m. EDT on 19 April. Endeavour quickly cleared the tower of the historic Pad 39A and rolled onto her back, bound for a 51.6-degree-inclination orbit and a rendezvous and docking with the ISS, two days later. During this period, Rominger, Ashby, and Phillips oversaw a series of thruster “burns” to more closely align their orbit with that of the multi-national outpost, whilst Hadfield and Parazynski worked to prepare their bulky Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) space suits and Guidoni and Lonchakov prepared for cargo transfer operations.

Early on 21 April—having been awakened to the strains of Kenny Loggins’ song “Danger Zone”—the crew brought Endeavour to a point about 600 feet (180 meters) “below” the station, before Navy Top Gun grads Rominger and Ashby executed the final rendezvous. (Interestingly, Ashby graduated from the Navy’s famed Fighter Weapons School in 1986, the same year that the movie Top Gun and Loggins’ tune were released to worldwide acclaim.) With pinpoint finesse, Rominger docked smoothly at the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2 interface, at the forward-facing end of the U.S. Destiny laboratory, at 9:59 a.m. EDT. At the time of contact and capture, the two vehicles were flying high above the southern Pacific Ocean, just to the south-east of New Zealand.

In a similar fashion to STS-97, in the winter of 2000, the first meeting between the station’s incumbent Expedition 2 crew—which consisted of Commander Yuri Usachev of Russia, together with NASA astronauts Jim Voss and Susan Helms—and the seven flyers of STS-100 would not occur immediately. Hatches would remain closed until after Hadfield and Parazynski had completed their first EVA, since Endeavour’s cabin pressure had been reduced from its normal 14.7 psi to 10.2 psi, in order to accommodate “pre-breathing” requirements. That said, the astronauts briefly entered PMA-2 shortly after docking to retrieve a Pistol Grip Tool (PGT), left there by the Expedition 2 crew, which would be utilized during the EVA. In return, they left some supplies, including water containers, computer equipment, fresh food, film for the IMAX camera, and Flight Data File (FDF) documentation for Expedition 2.

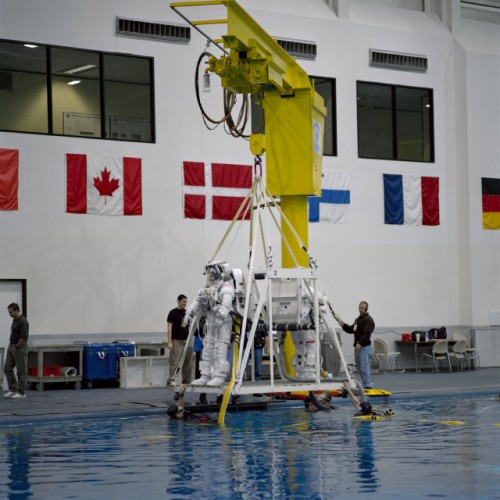

With their 6.5-hour EVA-1 timed to begin in the small hours of 22 April, Hadfield and Parazynski and their crewmates awakened early and set to work preparing tools and equipment and donning their EMUs. Assisted by “Intravehicular” (IV) crewman Phillips, Hadfield was outfitted in the “EV1” suit, with red stripes on the legs for identification, whilst Parazynski wore a pure white suit and carried the designation of “EV2.” Operating the shuttle’s RMS during the excursion were Ashby and Guidoni. In honor of Canada’s first spacewalk, the crew was awakened by the sounds of the late Canadian folk musician and singer-songwriter Stan Rogers.

As well as marking the 19th EVA conducted in support of ISS construction and maintenance, and the 63rd performed from the shuttle since April 1983, it admitted Canada into an exclusive “club” of spacewalking nations which, at the time, comprised just six other members: the former Soviet Union, the United States, France, Germany, Japan, and Switzerland. And with the delivery of Canadarm2 to the station, the opportunity would arise for the first parallel use of two robotic arms—on two different piloted spacecraft—at the same time. Figuratively and literally, the long-serving shuttle RMS would perform a unique “handshake” with its newer, larger, and more capable ISS counterpart.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace