A little over five months since making landfall on the blood-red surface of Mars, NASA’s remarkable Curiosity rover is heading towards its first sample-drilling target: a flat rock, laced with pale veins, which may yield clues about the planet’s wet past. For the team operating the $2.5 billion, six-wheeled vehicle, the drilling will be historic and particularly poignant, for the rock has been named in honor of former Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Deputy Project Manager John Klein, who died in 2011.

Curiosity touched down—with the aid of the revolutionary “Sky Crane”—beside the 18,000-foot peak of Aeolis Mons (“Mount Sharp”), within the yawning bowl of 96-mile-wide Gale Crater, early last August, and has already made significant inroads in our understanding of the Red Planet. Although public and media speculation was rife in November that the rover had found traces of microbial life, NASA has since admitted that no such evidence has been detected to date. Still, Curiosity has crept in an east-southeasterly direction across the desolate, ochre-hued landscape, toward Glenelg, a geologically important area marked by an intersection of three different terrain types, including layered bedrock. En-route to Glenelg, in late September, the rover conducted the first X-ray diffraction analysis of the internal structure of a soil sample on another world.

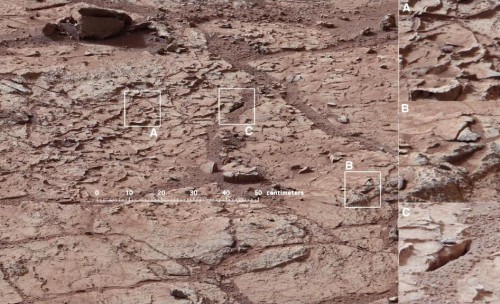

The upcoming drilling of “John Klein” will add yet another feather to Curiosity’s cap of capabilities. “John’s leadership skill played a crucial role in making Curiosity a reality,” said MSL Project Manager Richard Cook of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. The rock named in his memory lies in a region where the rover’s Mast Camera (Mastcam) and other instruments have revealed diverse—and unanticipated—geological features, including “veins,” nodules, cross-bedded layering, a lustrous, sandstone-embedded pebble, and possibly holes in the ground.

The surface environs of John Klein are quite different from the dry streambed of Bradbury Landing, a third of a mile to the west, where Curiosity landed five months ago. The rock lies within a shallow depression, nicknamed “Yellowknife Bay,” and orbital observation signals revealed that this fractured ground cools more slowly during each Martian night than nearby areas. “The orbital signal drew us here,” admitted MSL Project Scientist John Grotzinger of the California Institute of Technology, “but what we found when we arrived has been a great surprise. This area had a different type of wet environment than the streambed where we landed … maybe a few different types of wet environments.”

Drilling a sample on the Red Planet is by no means a straightforward process and Richard Cook described it as the most challenging activity since the landing. “The drill hardware interacts energetically with Martian material we don’t control,” he cautioned. “We won’t be surprised if some steps in the process don’t go exactly as planned the first time through.” The percussion drill has the ability to create a hole up to 1.6 cm in diameter and up to 5 cm deep. At John Klein, Curiosity will gather powdered samples from within the rock and use them to “scrub” the drill, before drilling and ingesting further samples, which will be mineralogically and chemically analyzed.

Light-toned veins, like those evident in this rock, have been seen to contain elevated levels of calcium, sulfur, and hydrogen in specimens previously examined by the rover’s laser-equipped Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) instrument. “These veins are likely composed of hydrated calcium sulfate, such as bassinate or gypsum,” said ChemCam team member Nicolas Mangold of France’s Laboratoire de Planetologie et Geodynamique de Nantes. “On Earth, forming veins like these require water circulating in fractures.” Additionally, Curiosity’s Mars Hans Lens Imager (MAHLI) has been used to explore sedimentary rocks in the region. These have included peppercorn-sized grains of sandstone—one of which exhibited a compelling gleam and a bud-like shape which has led to the nickname “The Martian Flower”—as well as traces of siltstone, finer than powdered sugar.

All of these samples are quite distinct from the pebbly conglomerate rocks found at Bradbury Landing, less than a mile away. “All of these sedimentary rocks [tell] us that Mars had environments actively depositing material here,” said Aileen Yingst, MAHLI Deputy Principal Investigator at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Ariz. “The different grain sizes tell us about different transport conditions.”

3 Comments

3 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:United States and North American News | David Reneke | Space and Astronomy News

Pingback:Curiosity Successfully Obtains First Sample from Martian Rock « AmericaSpace

Pingback:Curiosity Rover Selects Second Drilling Target on Mars « AmericaSpace