More than thirty years have passed since France became the first Western European nation to send a man into space. For almost two decades, the “high ground” of low-Earth orbit had been the almost-exclusive preserve of the United States and the Soviet Union, although from 1978 a handful of pliable Communist countries in Eastern Europe and Asia had sent their own token cosmonauts into space aboard Russian Soyuz vehicles. The Premier Vol Habité (“First Manned Flight”) of Frenchman Jean-Loup Chrétien in June 1982, however, was something different: the first occasion on which a Western-aligned pilot had flown with the Soviets. Today, Chrétien’s mission can be seen for what it was—a cynical piece of political gameplay in the deep, cold years of the late Cold War—but it also served to establish France on a remarkable journey which has seen its men and women involved in numerous pivotal missions throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and into the present century.

In the minutes after Chrétien’s launch aboard Soyuz T-6, with Soviet cosmonauts Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Aleksandr Ivanchenkov, on 24 June 1982, the onset of weightlessness and the view of Earth from orbit were experienced by a Frenchman for the first time in history. Pencils and pens, books, and checklists began to float comically before their eyes … and through the window the curvature of Earth and the darkness of space were cut by the ribbon-like line of the horizon. With a 25-hour rendezvous profile ahead of them to reach the Salyut 7 space station, it was imperative to get some rest. This was easier said than done. In the cramped confines of the Soyuz, Chrétien managed perhaps six hours of light sleep on his first night in orbit, but the strangeness of their surroundings got unnerving at times: the hum of the fans, the mixed signals entering eyes and ears and brain, and the realization that everything was weightless. Unlike many space travelers who preceded and followed him, the Frenchman did not suffer any instance of space sickness, although his appetite was noticeably reduced during the first day, and he expressed mild annoyance at his two veteran crewmates, who seemed perfectly adapted and ready to gobble down large meals from Soyuz’s pantry.

The meal which really got Chrétien back to normal was the one which they shared with Salyut-7 incumbent crewmen Anatoli Berezovoi and Valentin Lebedev. Docking at the space station provided some additional drama, when Soyuz T-6’s automatic rendezvous system failed, forcing Dzhanibekov to assume manual control. The computer correctly performed a braking maneuver at a distance of 2,600 feet, then reoriented the craft to position its docking mechanism in the proper position … but quickly sensed that the gyros were approaching “gimbal lock” and halted the attempt.

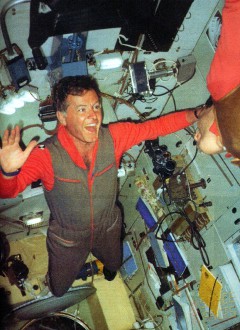

Soyuz T-6 was sent into an end-over-end spin and Dzhanibekov took over. From inside the station, Berezovoi and Lebedev saw the craft “just sitting there,” 650 feet away, with the occasional spurt from an attitude thruster as Dzhanibekov struggled to determine his position in relation to Salyut. At length, after receiving permission for the manual docking from Mission Control, routed through a tracking ship in the Strait of Gibraltar, he brought the two space vehicles safely into a metallic embrace at 10:46 p.m. Moscow Time on 25 June 1982. Three hours later, the new arrivals floated through Salyut’s hatch into the warm expanse of the space station and the welcome bear hugs of the two resident cosmonauts. For the first time in history, five cosmonauts were together in space.

Berezovoi and Lebedev had readied a hearty Russian dinner and Dzhanibekov and Ivanchenkov—whom Chrétien good-naturedly referred to as “the two monsters,” in view of their voracious appetites—wolfed down their second large meal of the day. Almost immediately, however, the work began on a complex program of French experiments, which encompassed life sciences, astronomy, and materials research. Studies were undertaken into the blood vessels of the brain, the acuity and depth of vision in space, the effects of cosmic radiation on biological specimens, and the threshold of color sensitivity, whilst observations of the night sky and investigations in infrared astronomy were made. The Frenchman employed much of the equipment aboard Salyut 7, including the Kristall (“Crystal”) furnace and components ferried aloft by Progress 13, to support a series of materials experiments focusing on temperature variations, the influence of capillary forces on the formation of aluminum and indium alloys, and the smelting and cooling of new metals.

Returning to Earth on 2 July after eight days in space was almost delayed by Dzhanibekov, the commander, himself. “He was late to get on his seat,” in the Soyuz, noted Chrétien, “because he was doing some stuff in the orbital [module] and he was still in his underwear when we were already sitting in our suits on our seats.” Every few minutes, the Frenchman would summon him and a flustered Ivanchenkov would alert him that if the hatch was not closed soon they would miss their undocking window, miss their re-entry window, be forced to wave off the landing attempt … “and they won’t be very happy down there” in Mission Control. At length, Dzhanibekov donned his suit and positioned himself in the central commander’s seat.

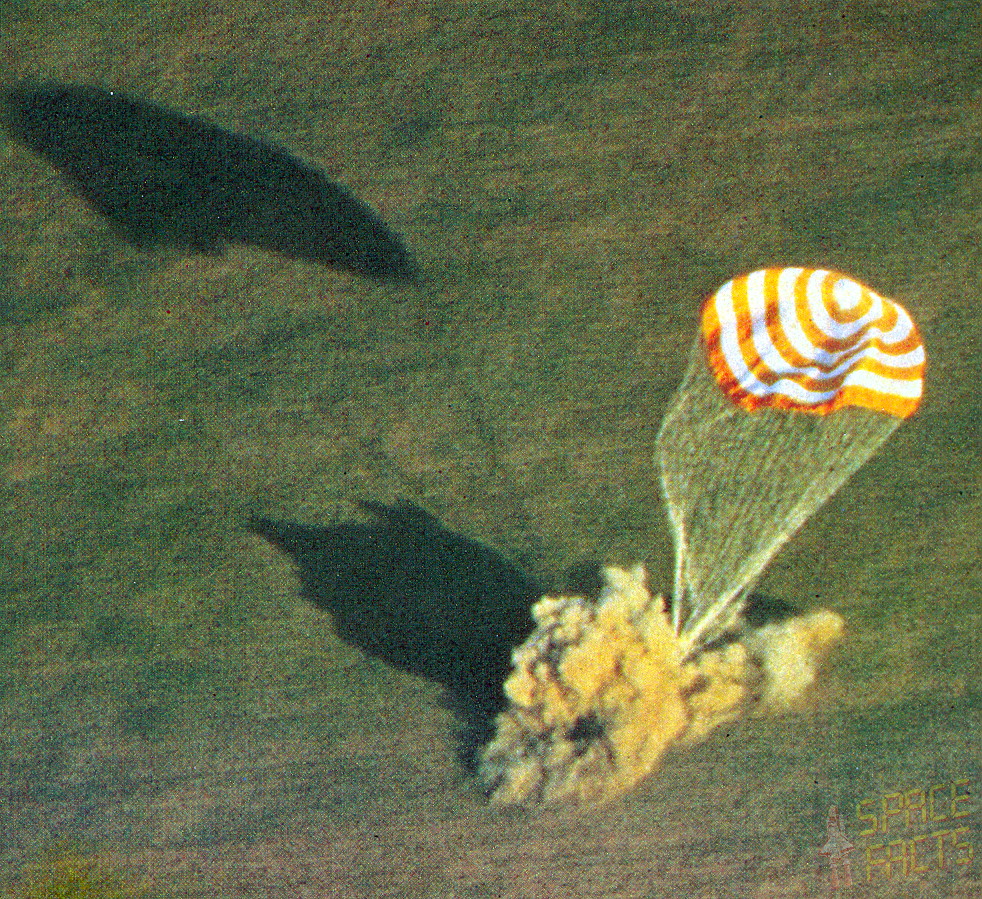

Re-entry felt like being in the midst of a ferocious storm, said Chrétien, and brought with it a sense of helplessness which was palpable. For a veteran test pilot, it worried him that he felt he had absolutely no control over the events going on beyond the Soyuz. With the worst of the re-entry heating behind them, their spacecraft descended, meteor-like, into Soviet territorial airspace and, at length, Chrétien could actually see their landing spot. Through his tiny window he beheld the desolate steppes of Kazakhstan, across which scurried hundreds of military personnel, dozens of trucks, a handful of helicopters … and the tractors and horses of intrigued locals, awaiting the latest visitors from the heavens. Touchdown came in the gathering gloom of the late summer’s afternoon, at 5:21 p.m. Moscow Time, bringing to a close the first Soviet mission to feature a participant from a Western-aligned, non-Communist nation.

Yet although the flight of Soyuz T-6 cemented a measure of harmony in the heavens, it did little to convey goodwill on the ground. More than two years earlier, in December 1979, tanks bearing the Hammer and Sickle had rumbled into Kabul, kicking off a vicious war with native mujahideen fighters, which met with enormous international condemnation. Cast against this ugly backdrop of communist aggression, France had the misfortune of becoming the first Intercosmos nation to fly with the Soviets in the wake of the invasion of Afghanistan … and her close ties with the United States and, more broadly, her intimate involvement with NATO meant that relations were extremely strained in the early 1980s. In fact, for Chrétien and Baudry there was no official welcoming ceremony upon their return to French soil. “They had told the press that we were not coming that day,” Chrétien recalled, “so we arrived like tourists and the only people welcoming us at the airport in Paris … were the people from the Soviet Embassy!”

For the nation’s first spationaut it was fine, because he could go on vacation and he was free from demands for speaking engagements and public relations visits. Nevertheless, he said, it was strange that the very people who had decided to send him into space were now keen to ignore him and his Premier Vol Habité (“First Manned Flight”). It must also have been saddening that such a historic episode in France’s long history should have been so neglected, on the basis of disagreements over political ideology and foreign policy.

By the time Chrétien next flew into space, again with the Soviets, in November-December 1988, and became the first non-Russian and non-U.S. spacefarer to make an EVA, relations had warmed between the two nations. The stance of Mikhail Gorbachev, who became General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985 and promulgated a new attitude of openness and political restructuring, placed the Soviet Union on a quite different diplomatic footing with the West than had been experienced during the tense days of his predecessors. Russia’s courtship of France blossomed in the post-Soviet era, with Michel Tognini, Jean-Pierre Haigneré, and Claudie André-Deshays (who later married Haigneré) spending extended durations aboard Mir in the early to late 1990s.

The United States, too, saw France as an ally in its space endeavors through the European Space Agency (ESA). Already, Patrick Baudry—with Jean-Loup Chrétien as his backup—had flown as a shuttle payload specialist in June 1985, but from the early 1990s a number of French ESA astronauts flew as dedicated mission specialists and aboard the International Space Station. Jean-François Clervoy flew three times, including a flight to Mir and the third Hubble servicing mission, whilst Chrétien and Tognini both flew aboard the shuttle. In the interim, their countryman Jean-Jacques Favier flew as a payload specialist on STS-78, and in mid-2002 Philippe Perrin became the first Frenchman to perform EVAs in support of International Space Station assembly operations. Since Perrin’s flight, Léopold Eyharts participated in a six-week expedition to the ISS in early 2008 and, at the time of writing, remains the most recent Frenchman to have entered orbit. Although Thomas Pesquet was selected in 2009, and widely tipped to fly aboard Expedition 46/47 in November 2015-May 2016, his slot has been taken by Britain’s Tim Peake. It therefore seems likely that Pesquet will fly in late 2016, more than three decades after France’s adventure in human space exploration first began.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will begin a series of articles to commemorate the anniversary of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, which marked the first joint U.S.-Soviet manned space mission, way back in July 1975.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Premier Vol Habité: The Story of France’s First Man in Space (Part 2) | Space Safety Magazine