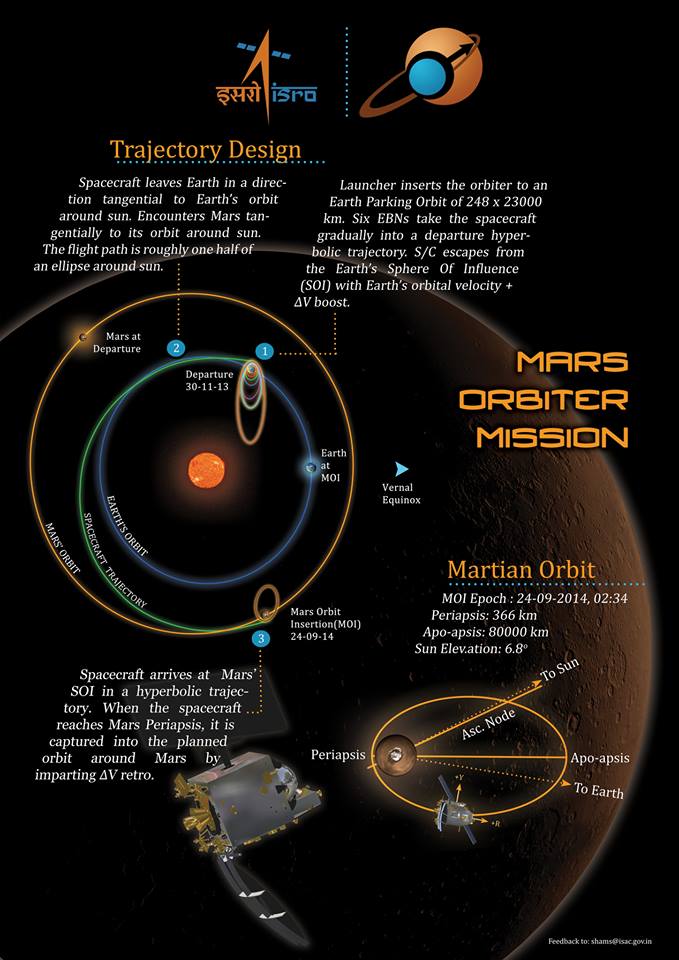

One week since its rousing 5 November liftoff atop the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), India’s first mission to Mars seems to have recovered well from its first hiccup, and the apogee of its steadily-increasing orbit has now reached about 73,720 miles (118,642 km) from the Home Planet. With four of its six orbit-raising maneuvers now satisfactorily concluded, the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM)—also known as “Mangalyaan” (Hindi for “Mars Craft”)—is now less than three weeks away from its planned departure from Earth on 30 November/1 December. According to the trajectory design, MOM/Mangalyaan will traverse interplanetary space for 300 days and reach Mars in September 2014.

Whereas NASA’s missions to the Red Planet, including next week’s planned launch of the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft, typically depart Earth orbit atop more powerful boosters and are injected directly onto a trans-Mars trajectory, the relatively limited propulsive yield of the PSLV and of MOM/Mangalyaan’s 400-Newton-thrust Liquid Apogee Motor (LAM) has made this infeasible. Instead, India’s spacecraft was inserted very precisely into a highly elliptical Earth orbit of about 155 x 14,600 miles (250 x 23,500 km) by the PSLV and was then tasked to execute a series of six engine firings over a period of several weeks to steadily increase its apogee to a maximum of about 133,600 miles (215,000 km), from which it will escape Earth’s Sphere of Influence and establish itself on a hyperbolic trajectory to reach Mars.

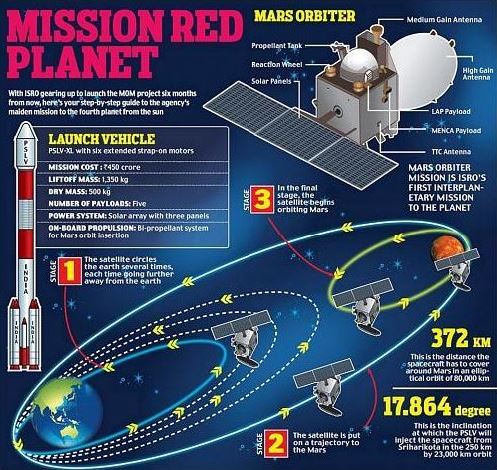

Developed by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the 2,980-pound (1,350-kg) MOM/Mangalyaan is equipped with five scientific instruments—the Methane Sensor for Mars (MSM), Mars Colour Camera (MCC), Mars Exospheric Neutral Composition Analyser (MENCA), Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (TIR), and Lyman-Alpha Photometer (LAP)—and will demonstrate the technology needed to deliver a spacecraft to the Red Planet and conduct meaningful science. Upon arrival in September 2014, it will spend at least six months orbiting Mars, focusing on the morphology, topography, and mineralogy of the surface, together with the dynamics of its thin upper atmosphere, its loss of water, the influence of solar wind and radiation, and the nature of its moons, Phobos and Deimos.

Following its launch at 2:38 p.m. IST (4:08 a.m. EST) on Tuesday, 5 November, from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre, on India’s southern barrier island of Sriharikota, MOM was placed into an orbit which very closely paralleled pre-flight projections, inclined 19.27 degrees to the equator and with an orbital period of slightly less than seven hours. After separation from the final stage of the PSLV, the spacecraft’s main antenna and solar arrays were successfully deployed and the first orbit-raising burn of the LAM began at 1:17 a.m. IST on Thursday, 7 November. Under the command of ISRO’s Telemetry, Tracking, and Command Network (ISTRAC) in Peenya, Bangalore, the engine was ignited for 416 seconds and lifted MOM/Mangalyaan’s apogee to 17,550 miles (28,852 km).

This first burn was followed, at 2:18 a.m. IST Friday, by a 570-second firing to push the apogee further to 24,970 miles (40,186 km). The LAM ignited for the third time at 2:10 a.m. IST Saturday, increasing the spacecraft’s high point to 44,500 miles (71,636 km). According to ISRO, many parameters of MOM/Mangalyaan’s systems and redundancy features were evaluated during this period. “During the first three orbit-raising operations,” it was explained, “the prime and redundant chains of gyros, accelerometers, 22-Newton attitude control thrusters, attitude and orbit-control electronics, as well as the associated logics for their fault-detection isolation and reconfiguration, have been exercised successfully.” ISRO added that prime and backup star sensors and associated instrumentation continued to function normally.

With the fourth burn, ISRO expected MOM/Mangalyaan to expand its apogee even further to beyond 62,100 miles (100,000 km) from Earth. This burn should have imparted an incremental velocity of around 426 fps (130 m/sec), but actually added just 114 fps (35 m/sec), raising the apogee to just 48,640 miles (78,276 km). “During the fourth orbit-raising operations,” ISRO explained, “the redundancies built-in for the propulsion system were exercised.” This work included energizing the primary and redundant coils of the solenoid flow control valve of the LAM and logic for thrust augmentation by the attitude-control thrusters. “However,” ISRO continued, “when both primary and redundant coils were energized together, as one of the planning modes, the flow to the Liquid Engine stopped. The thrust-level augmentation logic, as expected, came in and the operation continued using the attitude-control thrusters. This sequence resulted in reduction of the incremental velocity.” ISRO noted that, in spite of the thrust shortfall, MOM/Mangalyaan remained healthy and “a supplementary orbit-raising operation” was planned for Tuesday, 12 November. This supplementary burn started at 5:03 a.m. IST yesterday (Tuesday) and lasted 303.8 seconds, with MOM’s apogee now successfully raised to 73,720 miles (118,642 km).

Two further LAM firings—the next of which is set for Saturday, 16 November—will position the spacecraft for its departure from Earth’s Sphere of Influence and ISRO expects to use about 795 pounds (360 kg) of the spacecraft’s propellant supply. MOM/Mangalyaan will be established on the Mars Transfer Trajectory at 12:42 a.m. IST on 1 December. “The spacecraft leaves Earth in a direction tangential to Earth’s orbit,” explained ISRO’s official brochure for the mission, “and encounters Mars tangentially to its orbit,” noting that these “minimum-energy” opportunities to reach the Red Planet under conditions of the best economy of propellant expenditure, mission duration, and trajectory design arise approximately every 780 days.

“The spacecraft arrives at the Mars Sphere of Influence in a hyperbolic trajectory,” continued ISRO. “At the time the spacecraft reaches the Closest Approach to Mars (periapsis), it is captured into planned orbit around Mars by impacting delta-V retro, which is called the Mars Orbit Insertion (MOI) manoeuvre.” According to current mission plans, MOI will occur at 2:34 a.m. IST on 24 September 2014 (5:04 p.m. EDT on 23 September), and MOM/Mangalyaan will enter an orbit of 310 x 50,000 miles (500 x 80,000 km), inclined 150 degrees. In this highly elliptical orbit, it will circle the planet once every 76.72 hours. Quoting ISRO officials, FirstPost India noted that the minimum life of MOM/Mangalyaan in Mars orbit is six months, but hopes are high that it will exceed this target.

This mission is both highly ambitious and highly unlikely for the world’s second most populous nation, and its merits and motivations have triggered considerable debate. It is described as “a technology demonstration project,” and its primary task is to prove that India can design, plan, manage, launch, and operate a deep-space mission across the enormous gulf to reach the Red Planet. It only received formal approval and a $41 million financial injection from the Indian government in August 2012. With anticipated costs as high as $100 million, the mission has unsurprisingly provoked debate from critics who feel that India could better spend the money on more down-to-earth issues, such as power failures, droughts, and the aftermath of Cyclone Phailin. Still, one government official retorted in a BBC interview that “India is today too big to be just living on the fringes of high technology.”

Hopes are high for MOM/Mangalyaan, as India sets out on a path to become the fourth discrete organization, nation, or group of nations to successfully send its own mission to Mars. Only Russia, the United States, and the member states of the European Space Agency (ESA) have accomplished this feat to date. Yet the stakes are even higher, particularly in the wake of the ignominious fate of Russia’s Fobos-Grunt and China’s Yinghuo-1 spacecraft, which failed to leave Earth orbit in November 2011 and burned up in the atmosphere a few weeks later. “For Mars, there were 51 missions so far the world around,” ISRO Chairman Dr. K. Radhakrishnan told India’s Economic Times last week, “and there were 21 successful missions. It’s a complex mission.” He pointed out that the difference between success and failure in any space enterprise “is very, very thin,” but stressed that even a failure provides a stepping stone to success. Coming less than two years after the Fobos-Grunt and Yinghuo-1 failure, Dr. Radhakrishnan denied overt competition with China and scoffed at the notion of a “race” to Mars between the two nations. “We are in competition with ourselves,” he said, “in the areas that we have charted for ourselves. Each country has its own priorities.”

Dr. Radhakrishnan has admitted that the MOM/Mangalyaan mission will be a challenge, an opportunity, and a matter of national pride, and certainly illustrates the growing maturity of India’s space program. “Such scientific missions post very tough challenges to technologists,” he said. “Some of the outcomes—for example, the in-built autonomy we are providing in this spacecraft—can become a reality as a product or system and be used in satellites to improve their efficiency. So they percolate to application, which is our main objective. It could be something like forecasting cyclones. There is always relevance for a mission such as this.”

The spacecraft’s in-built autonomy has been incorporated in response to a recognition that the maximum Earth-Mars Round Trip Light Time (RLT) will be 42 minutes, making it “impractical to micromanage the mission from Earth with ground intervention.” As a consequence, MOM/Mangalyaan adopts autonomous Fault Detection, Isolation, and Reconfiguration (FDIR) logic, none of whose actions will disrupt the spacecraft’s Earth Pointing Attitude. ISRO considers this system to be essential during any communications problems or interruptions—during eclipses, for example—and it will safeguard the spacecraft during its insertion into Martian orbit.

Conditions in interplanetary space and in orbit around the Red Planet have also been simulated during numerous ground tests. The performance characteristics of the critical Liquid Apogee Motor have been evaluated in ISRO’s High Altitude Test Facility, whilst thermal balance tests have yielded baseline data for Mars radiation flux and have helped to validate thermal models. In order to handle the frigid cold of a Martian eclipse, MOM/Mangalyaan solar array “coupons” have been subjected to temperature conditions as low as -200 degrees Celsius, qualifying both the cells and their bonding agents. The spacecraft’s communications system has been exhaustively tested and verified by both ISRO and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) of Pasadena, Calif., whose Deep Space Network (DSN) will work alongside the Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) in tracking MOM/Mangalyaan. These tests have demonstrated “communications management” at the predicted distance between Earth and Mars at the point of MOI, an estimated 133 million miles (214 million km), and after six months in orbit, an estimated 233 million miles (375 million km).

Much criticism has been leveled at India in recent weeks, with some observers expressing open condemnation that ISRO is executing such a mission, when it has pressing problems at home. The process of reconstruction in the wake of Cyclone Phailin’s ravages is still underway, and last year’s droughts, coupled with endemic poverty in the country, are both noteworthy and worrisome. Yet questions of the wisdom of “wasting” money on a space program have been asked time and again throughout history. Some have argued that space exploration, by its very nature, plays a key role in advancing a nation in a technological sense and helping to position its people onto the world stage. Last year, an Indian government official told the BBC that “if we don’t dare dream big, it would just leave us as hewers of wood and drawers of water.” Whatever our individual perspectives might be, on the eve of India’s first voyage to Mars we can be certain of one thing: that these hewers and wood and drawers of water have collectively accomplished something quite remarkable.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

The author writes about the Indian Mars mission: “India could better spend the money on more down-to-earth issues, such as power failures, droughts, and the aftermath of Cyclone Phailin.”

This is a very odd statement, particularly about Phailin. It is because of the Indian space program that the Phailin casualties were limited to between 14-21 deaths (reported by US news agencies). Meteorology and remote sensing are the two most useful, practical, and important technologies made affordable by the Indian space program. You can’t get more down-to-earth than that. NASA certainly does not.

In contrast to the limited casualties in Phailin, 1833 people died during Katrina. Surely, an immensely rich country like the USA with its vast resources, greater wealth, etc could have performed better than India? Maybe NASA should spend money on more down-to-earth issues of greater relevance to the American people?

Thanks for the comment, Ratnam. However, if you re-read the quote in the context of the sentence, you will notice that it was preceded by “provoked debate from critics”. The sentence made reference not to my personal thoughts, but to criticisms expressed in recent weeks by individuals and within the world’s media about the necessity of MOM. Contrary to your comment, this mission is not for meteorology or remote-sensing (technologies which I wholeheartedly agree are vital and life-saving) but for the exploration of another world, which some have perceived may not directly improve the lives of people on Earth. Many Indian people live in conditions of far greater poverty and deprivation than those in the West. The MOM mission produced a large amount of criticism and praise, in equal measure, and although Phailin thankfully caused few fatalities, it did wreak a tremendous amount of infrastructural damage (including to the Andhra Pradesh region). My article attempted to address the concerns of proponents and opponents to this mission. Thanks again for your thoughts.