The European Space Agency’s Science Programme Committee will announce its decision next week regarding the selection of the next medium-class space science mission to be developed as part of the agency’s Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 plan. The leading candidate in the selection process, the PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars, or PLATO space observatory, was recently shortlisted from a group of four more mission proposals by the agency’s Space Science Advisory Committee for further study.

The field of exoplanetary science has been revolutionised in recent years by the findings of both the joint ESA/French Space Agency CoRoT and NASA’s Kepler space telescopes. These missions have provided an incredible wealth of data, allowing for the discovery of hundreds of new exoplanets, while offering astronomers a glimpse of the great diversity of worlds that exist in distant exoplanetary systems. The realisation that the Milky Way galaxy is probably teeming with planets has resulted in the need for more advanced follow-up exoplanet-hunting space missions. The ultimate goal is to find the Holy Grail of planetary astronomy—an Earth-type planet inside the habitable zone of its star.

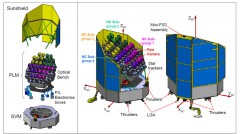

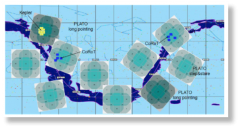

Reflecting the need for such a mission, ESA’s Space Science Advisory Committee’s selection of PLATO in late January, if approved, would give a huge boost to the search for Earth-sized terrestrial exoplanets that could have the right conditions for the emergence of life as we know it. PLATO’s scientific payload will consist of a platform of 34 small-aperture cameras, each consisting of four Charge-coupled devices or CCDs, with resolutions of up to 4519 x 4510 pixels, by far surpassing that of both Kepler and CoRoT. This overall higher resolution of the mission will provide astronomers with unprecedented views of approximately 1 million stars across half of the sky. The spacecraft will make continuous, long-duration observations of two sky fields for a maximum of 3 years, which will be complemented by a “Step-and-Stare” shorter-period survey of several sky fields, for a few months each.* “Long pointings will be devoted to surveys for small planets out to the Habitable Zone of solar-like stars. Short pointings will be devoted to shorter-period planet detections and will address a number of different science cases. The proposed observing strategy aims at covering a large fraction of the sky, thereby maximizing the number of well-characterized planets and planetary systems, in combination with wide-angle long pointings that will significantly increase the number of accurately known terrestrial planets at intermediate distances [from their stars] up to 1 Astronomical Unit [the average Earth-Sun distance],” writes PLATO’s science team in their mission proposal to ESA.

PLATO will hunt for planets using the “transit” method, utilised also by Kepler and CoRoT. By studying the light curves of stars, it will monitor for any drop in their brightness that would indicate the passage of a transiting planet. With its wide-field of view, the observatory will be able to map exoplanets across much of the sky. “PLATO will observe up to 1,000,000 stars and detect and characterize hundreds of small planets and thousands of planets in the Neptune to gas giant regime out to the habitable zone,” reads the mission proposal. “It will therefore provide the first large-scale catalogue of bulk characterized planets with accurate radii, masses, mean densities and ages. This catalogue will include Earth-like planets at intermediate orbital distances, where surface temperatures are moderate.”

Another field of study that would benefit greatly from the mission is astroseismology, which is the study of the interiors of stars by measuring their oscillations. In much the same way that a geologist can measure the propagation of seismic waves through the Earth and deduce the structure of our planet’s interior, astronomers can similarly study the oscillation patterns in a star’s frequency spectra to better understand the star’s internal structure. PLATO will observe many different families of stars, from hot, massive blue sub-dwarfs, to variable stars, to white dwarfs, red giants, and stars inside star clusters.This can lead to a better understanding of the physical processes which govern stellar evolution from the early development cycles of a star to the last stages of its life.

If it is finally chosen for implementation, PLATO will launch in 2024 onboard a Soyuz-Fregat rocket and placed in an orbit around the L2 Sun-Earth Lagrangian point, approximately 1.5 million kilometers away from our planet. Throughout the duration of its six-year primary mission, PLATO will complement the discoveries made by Gaia, another space observatory recently launched by ESA, and those made by the joint NASA/ESA James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled for launch in 2018. The hundreds of terrestrial exoplanets that are expected to be discovered by PLATO will be prime targets for follow-up observations by the JWST, whose superior optics and science instruments will allow for detailed spectroscopic analyses of these planets, helping to detect any bio-signatures that would be present in their atmospheres.

The announcement of the agency’s Science Programme Committee final selection is scheduled during its meeting on February 19-20. Given the fact that most of the Committee’s past decisions were almost always in agreement with the Space Science Advisory Committee’s proposals, it is highly likely that the PLATO mission will be similarly given the “go-ahead” for implementation by the European Space Agency. If so, PLATO will become the third medium-class mission in ESA’s Cosmic Vision program, following on the heels of the Solar Orbiter and Euclid missions, which were the first medium-class missions of the program to be selected, currently scheduled for launch in 2017 and 2020 respectively. The budget for these medium-class series of missions is approximately 600 million euros ($820 million), with the mission costs distributed between the ageny’s 20 member states.

The other four candidates that PLATO has competed against include the Exoplanet Characterisation Observatory, or EchO, another exoplanet-hunting mission; the MarcoPolo-R mission proposal for studying a Near-Earth Asteroid; the Large Observatory For X-ray Timing, or LOFT, for the study of black holes and neutron stars; and the Space-Time Explorer and Quantum Equivalence Principle Space Test, or STE-QUEST, for the study of fundamental physics phenomena predicted by Einstein’s General Relativity theory. The PLATO mission has been in ESA’s list since 2007, but wasn’t selected during the 2011 selection process for the first two medium-class mission launch opportunities, when the space agency adopted the Solar Orbiter and Euclid missions instead. However, PLATO was allowed to compete for the third launch slot in the medium-class category, finally earning the favor of ESA’s Space Science Advisory Committee last month. Given the approval of the Science Programme Committee next week, PLATO will await for ESA’s official, final approval to come sometime during late 2015, after the space agency’s different member states have expressed their formal commitment and financial support for the mission.

Provided that everything goes according to plan, the PLATO mission will usher a new age in exoplanet discovery. “The PLATO mission promises to perform the discovery of and first systematical characterization, of thousands of Earth-sized or smaller exoplanets, out to 1 A.U. orbital distance from their respective host stars, delivering exact radii and uniquely high precision ages,” concludes the PLATO mission proposal. “Building on the CoRoT, Kepler, [and the currently in development] CHEOPS and TESS missions, PLATO will be the only mission dedicated to such detection and characterisations and will be complemented by facilities for spectroscopic follow-up, such as the European Extremely Large Telescope [and the] James Webb Space Telescope, or future missions dedicated to exoplanet atmospheric spectroscopy.”

With all these different ground- and space-based observatories scheduled to come online during the next few years, the 2020s promise to be really exciting times for the field of exoplanetary astronomy, possibly providing us with the first glimpses of an alien Pale Blue Dot, serenely orbiting a distant star somewhere inside the vast expanses of our Milky Way galaxy.

*The author would like to thank reader Laszlo Molnar, for pointing out a technical error that had appeared originally in the article, and for providing with the correct details of PLATO’s observing strategy.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

PLATO represents a quantum leap forward in the eventual discovery of life-sustaining planets. The project must proceed, especially as our understanding of exoplanets becomes ever more a fundamental part of space scientific thought and inquiry. Yes, the 2020’s will not only be an exciting era in space exploration but the decade will also bear witness to a transformational shift in how we view our place in the cosmos.

Most unequivocally a quantum leap forward Tom, especially so when viewed from the perspective that it was as recent as 1930 that Clyde Tombaugh scrutinized thousand of images on photographic plates to discover . . . Pluto. Yet another in a succession of outstanding articles Leonidas, and I am certain that I speak for many readers who are impressed by, and appreciative of, your research and writing skills. Thank you for your efforts on our behalf.

Thank you very much, Karol and Tom! Your kind words and support, are greatly appreciated.

“PLATO will also feature a set of two additional cameras with a resolution of 4519 x 2255 pixels, for conducting a “Step-and-Stare” mode of short-period pointings to complement the long-duration observations of the main 32-telescope ensemble.”

That sentence confuses two different things. The two special cameras will make short exposures (every 2.5 sec instaad of the normal 25 s exposures) to observe the brightest stars in every field without saturating the CCDs.

The entire spacecraft with all cameras will observe two long-duration fields for 2-3 years, followed by a “Step-and-Stare” survey of the sky, observing several fields for a few months each.

Thank you very much Laszlo, for pointing out the mistake. I have updated the article accordingly.