“Abandon hope, all ye who enter here”

— Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, 1308-1321

The inscription above the entrance of Hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy was meant to greet all the unlucky souls that were damned to burn in it for all eternity. Yet this fictional construct could also apply to the real-life Venus as well, Earth’s so-called “twin sister” in the Solar System, for it perfectly describes the planet as it has been revealed to us by the various robotic orbiters and landers that have studied it in the past. The latest in the long list of robotic Venusian explorers, the European Space Agency’s Venus Express spacecraft, has recently concluded an eight-year study of the infernal planet and is getting ready to dip into its atmosphere, in the hopes of gathering valuable engineering data on the effects of aerobraking that could prove very helpful to ESA’s mission planners in the future.

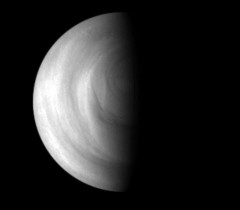

Having almost the same size and density as Earth, Venus was largely seen as an inhabited, hot tropical version of our home planet before the dawn of the space age. The many dozens of robotic missions that had visited it during the past 50 years have instead revealed a world that is more inhospitable than a house kitchen oven. Replete with a blistering hot surface temperature that exceeds 460 degrees Celsius and a pressure almost 93 times that of Earth’s, enveloped by a crashing atmosphere that is mostly composed of carbon dioxide and covered with clouds consisted of highly corrosive sulfuric acid, Venus seems anything but Earth’s sister planet. Yet, despite these extreme conditions, it is far from an uninteresting world, as evidenced by the fascinating results that have been beamed back by the Venus Express spacecraft.

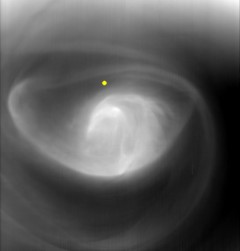

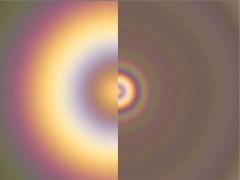

Based on the design of the equally successful Mars Express orbiter, which continues to study the planet Mars since arriving there in 2003, Venus Express was ESA’s first-ever mission to orbit Venus, conceived as part of the agency’s Cosmic Vision science program. Designed and built by EADS Austrium, the 1,276-kg spacecraft was launched in November 2005 on top of a Soyuz-FG/Fregat rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan and settled into a 24-hour highly elliptical 66,000 by 250 km polar orbit in April 2006. Having braced the intense heat and radiation environment at the vicinity of the planet, as well as several temporary blackouts of its star trackers from the effects of incoming solar coronal mass ejections, the spacecraft successfully concluded its eight-year science mission earlier this month, a mission that had already been extended by ESA no fewer than four times. Throughout its mission, the spacecraft conducted the most detailed study of the chemical composition, structure, and dynamic interactions of the Venusian atmosphere with the surface to date, with the help of its science payload consisting of seven instruments. Highlights of the mission include a series of measurements indicating that the Venusian atmosphere’s already super-fast winds are accelerating even further, tantalising evidence for present-day volcanic activity on the surface and for the existence of an ozone layer and carbon dioxide snow in the upper atmosphere, observations of the ionosphere’s comet-like dynamics, as well as exciting, detailed views of the planet’s south polar vortex and the detection of a “glory,” a rainbow-like feature that is seen for the first time in the atmosphere of another planet.

As exciting as these discoveries were, perhaps one of the more unexpected results to come out of the mission was surprising evidence suggesting that Venus’ rotation may have slowed down significantly over a period of 20 years, since NASA’s Magellan mission explored the planet during the early 1990s. Launched in 1989, the Magellan spacecraft was the first to make a high-resolution radar mapping of 98 percent of Venus’ surface, penetrating its obscuring thick cloud decks and providing us with unprecedented views of the planet’s topography for the first time. In addition to these radar views, Magellan also collected high-resolution gravity data during its four-year mission, which helped scientists to clock the planet’s slow rotation at being equal to 243,0185 Earth days. After arriving in 2006, the Venus Express spacecraft started studying the dynamic interactions between the planet’s atmosphere and surface, with its onboard Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer, or VIRTIS, an imaging spectrometer sensitive to ultra-violet, visible, and infrared wavelengths between 0.25 and 5µm. The results showed that some surface features were displaced by as much as 20 km from where they should have been, compared with the radar data from Magellan. The only explanation accounting for the discrepancies between the two spacecrafts’ different data sets was that the planet’s rotation had slowed down by approximately 6.5 minutes since the early 1990s. “When the two maps did not align, I first thought there was a mistake in my calculations as Magellan measured the value very accurately, but we have checked every possible error we could think of,” says Nils Müller, a planetary scientist at the DLR German Aerospace Centre’s Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin.

Another interesting result to come from the mission was the confirmation of the huge amounts of hydrogen escaping the planet’s atmosphere, which were found to be roughly twice that of oxygen, indicating a time in the past when Venus might have been much more habitable than it is today. Because Venus lacks an internal magnetic field, the solar wind coming from the Sun penetrates deep into the planet’s atmosphere, continuously striping it from elements like hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. The rate of hydrogen loss measured by the Venus-Express spacecraft indicates that far larger quantities of the light element existed in the planet’s atmosphere during the distant past, which combined with the oxygen that was also present could have led to the formation of huge amounts of liquid water on the surface, transforming the early Venus into a possibly habitable world. Past measurements made with NASA’s Pioneer-Venus mission in the 1970s seem to support this hypothesis, by showing that the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen on the atmosphere of Venus is more than 150 times greater than anywhere else in the Solar System, leading many scientists to speculate that the planet could have been covered by vast oceans of liquid water early in its history, which was subsequently lost into space through continuous atmospheric loss.

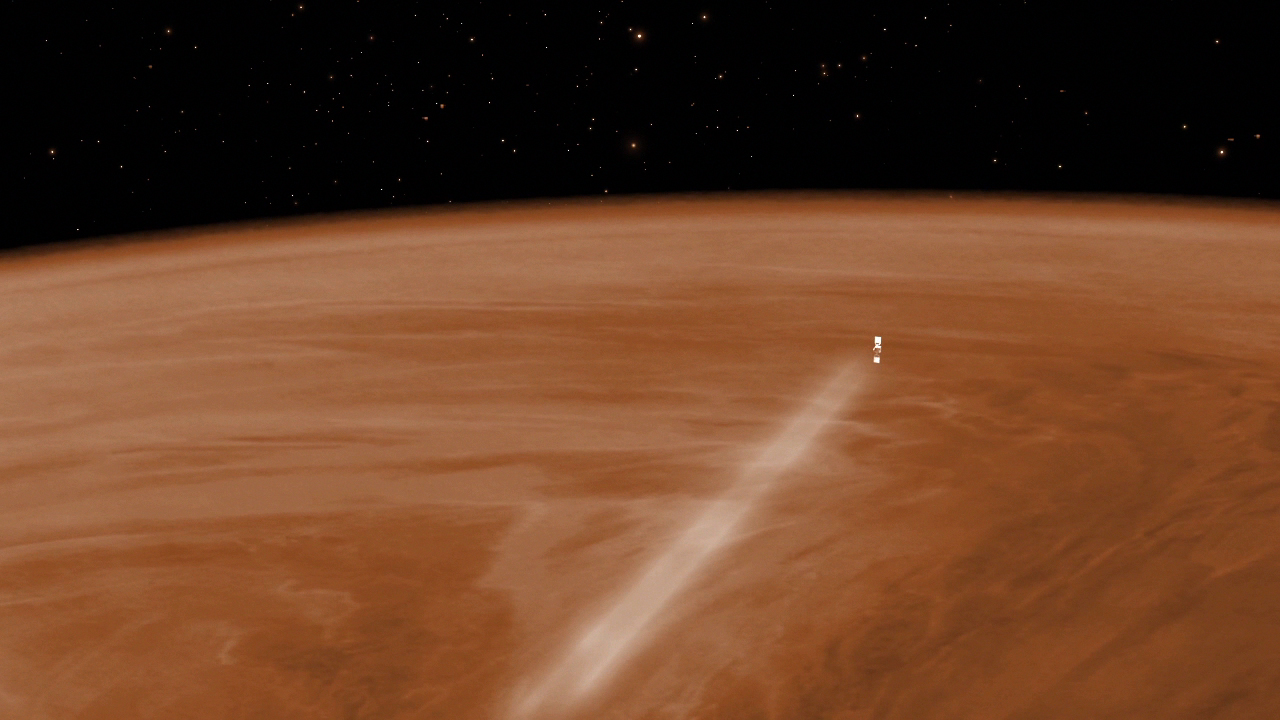

Now, having completed its mission, Venus Express is getting ready for its new role as a daredevil which includes a final plunge into the Venusian atmosphere. Engineers on the ground are planning to lower the spacecraft’s orbit in such a way so that it passes through the upper atmospheric layers, during a risky aerobraking campaign which is scheduled to take place between 18 June and 11 July. “We have performed previous short ‘aerodrag’ campaigns where we’ve skimmed the thin upper layers of the atmosphere at about 165 km, but we want to go deeper, perhaps as deep as 130 km, maybe even lower,” says Patrick Martin, ESA’s Mission Manager for both the Mars and Venus Express spacecraft. “It is only by carrying out daring operations like these that we can gain new insights, not only about usually inaccessible regions of the planet’s atmosphere, but also how the spacecraft and its components respond to such a hostile environment.” A second goal of the aerobraking campaign is to provide engineers with critical data on the spacecraft’s ability to effectively manuever through the upper atmosphere. Aerobraking is a technique for lowering the speed of planetary probes during orbit insertion around planets with an atmosphere, without the need to use excessive amounts of fuel. The mastering of this technique could prove very useful for ESA’s mission planners in the future. “The campaign also provides the opportunity to develop and practise the critical operations techniques required for aerobraking, an experience that will be precious for the preparation of future planetary missions that may require it operationally,” says Paolo Ferri, Head of Planetary Mission Operations at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

Despite the high-risk nature of the whole endeavor, it is hoped that the spacecraft might survive the aerobraking maneuvers and continue operating for a few more months, before finally being decommissioned later in the year with a final death dive into Venus’ hellish atmosphere. Whatever the future holds for the intrepid robotic spacecraft, however, its mission has been a tremendous success, leading to many new exciting discoveries, which in turn have led to a new series of questions regarding Earth’s closest planetary neighbor. “Venus Express has taught us just how variable the planet is on all timescales and, furthermore, has given us clues as to how it might have changed since its formation 4.6 billion years ago,” says Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s project scientist for the mission. “[It] has penetrated deeper into the mysteries of this veiled planet than anyone ever dreamed, and will no doubt continue to surprise us down to the last minute.”

Following the conclusion of the Venus Express mission, our next chance to further study Earth’s sister planet will come in 2015, when Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft will attempt for the second time to enter into orbit around the planet. Having been launched in May 2010, Akatsuki arrived in the vicinity of Venus the following December, but its thrusters underperformed during the critical orbit-insertion burn, which led to the spacecraft flying past the planet, to return again next year. Provided that everything goes according to plan, Akatsuki will finally enter into orbit around a world that has proven to be much more interesting and enticing than what our perceptions of it has left us to realise.

Video Credit: ESA/C.Carreau

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Leonidas’s article provides a wealth of detailed information on Venus that offers the reader important insights into planetary development. It is another reason why we must press ahead with robotic and eventually manned exploration of our “neighborhood.” Thanks, Leonidas!