When the history of our galaxy is written,

and for all any of us know it may already have been,

if Earth gets mentioned at all it won’t be because its inhabitants visited their own Moon.

That first step, like a newborn’s cry, would be automatically assumed.

What would be worth recording is what kind of civilization we earthlings created

and whether or not we ventured out to other parts of the galaxy.

— Michael Collins, “Liftoff: The Story of America’s Adventure in Space” (1989)

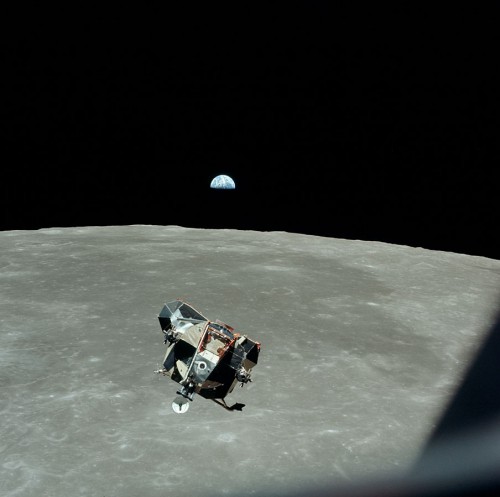

Between 60,000 and 100,000 years ago, the first members of anatomically modern humans took their first steps out of the East African savannas, which had been the cradle of human evolution for more than 2.5 million years, to populate the rest of the land of what was an essentially unknown planet. Forty-five years ago this week, humans took their next steps up the evolutionary ladder by walking on the Moon, at a place called Sea of Tranquility, during the Apollo 11 mission in 20 July 1969—the first time that any human beings had ever walked anywhere outside of their own planet. These decisive first steps on another world were equally met with exhilaration, hope, and wonder as well as skepticism, fear, and condemnation. The reasons for these widely varied reactions to humanity’s single greatest achievement ever have been multifaceted and intertwined. The second part of this article examined the American public’s opposition to the Apollo missions to the Moon and toward the space program in general, based on financial arguments pertaining to the former’s supposedly unacceptably high costs. This article will focus on some of the deeper, unconscious emotional, ideological, and cultural reasons behind this opposition. Although the reasons explored here are by no means the only ones that affect space policy decisions, they nevertheless provide a valuable glimpse at the public’s deeper fears regarding space exploration, which in turn influence its attitude toward it.

Space and culture

The late professor of anthropology Dr. Ralph Linton described culture as “a configuration of learned behaviors and results of behavior whose component elements are shared and transmitted by the members of a particular society.” Similarly, in his book “Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures,” Dr. John Paul Lederach, a professor of sociology and International Peace building at the University of Notre Dame, Ind, defines culture as “the shared knowledge and schemes created by a set of people for perceiving, interpreting, expressing, and responding to the social realities around them.” Being a product of human society, cultural values, like human beings, are not static and rigid but change and evolve with the passage of time, as human societies respond to the events around them, which are often unexpected or even revolutionary. This replacement of older societal norms with newer ones can sometimes be a painful process, which constantly reshape the values of societies and individuals alike, as well as the general perception of what is “normal,” slowly incorporating these changes into humanity’s overall cultural heritage.

This process of cultural change has been an accelerated one, particularly since the time of the Industrial Revolution, when the advent of new technologies and manufacturing processes greatly affected all aspects of everyday life, leading to major societal reforms. The development of both aviation and spaceflight during the 20th century could be similarly described as major technological revolutions as well, which had widespread, far-reaching, and unpredictable societal effects. The realisation that Man could now travel within the third direction of space, freed from the two spatial dimensions of the Earth’s surface that he was bound to for millenia, suddenly opened up a whole new realm of possibilities of human existence and new vistas of human thought and imagination. Yet, at the same time, the advent of spaceflight was in many ways a technological achievement that seemed to be ahead of its time. “The revolution of space flight … was one of the fastest and most remarkable ones in human history,” commented the late British science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke in his essay collection “1984, Spring: a Choice of Futures.” “Most of technological achievements arise naturally whenever a social need is followed by a relevant invention. The steam engine, the telephone and the automobile are some obvious examples. But to be quite honest, no one really needed any spaceships during the mid-20th century and there are many who’d wish that we didn’t have any … The imagination and dedication of just a handful of people … opened the space frontier decades before any plausible historical scenario … Some day we will be very glad that we went to the Moon in 1969 instead of 2001 or even 2051.”

This rapid and sudden advancement of the Space Age also triggered some deep-seated unconscious anxieties and irrational fears, in a general public which seemed to be largely unprepared for dealing with Man’s new role and purpose in this infinite realm of space. “On a scale of emotions, if one existed, [the public’s attitude towards the Apollo Moon landings] would probably run from apathy to zealousness, with a large area of confusion in between,” wrote Sandra Blakeslee in an article for the New York Times on July 17, 1969, in the aftermath of the historic launch of Apollo 11. “Some adults, while verbally uncertain of their feelings toward Moon exploration, are emotionally opposed, if not outright afraid of it. Some psychiatrists in fact, have called this phenomenon ‘future shock’. Instead of marching into the future in clear, demonstrable steps, many people feel catapulted into an alien age that they do not understand.”

Even long after the Apollo program had ended, when spaceflight had gradually entered the public’s consciousness as something relatively routine, these emotional reactions seemed to persevere. “Most people react viscerally to space as being a dark, cold place,” argued American novelist Norman Mailer in an interview for the OMNI magazine in July 1989 on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing. “They don’t want to have much to do with it. They’re intrigued, occasionally, when they see pictures of the Earth on television or when we’re talking to the astronauts, but the public response was not as deep and powerful as NASA had hoped it would be … I think there’s also an unconscious hatred [in the public’s mind] of the people who are going into space. I think a lot of people feel, in effect, that these guys are going to gut everything here and go out and leave us behind, that there may be an embarkation from the dying planet Earth to save a few of the species.”

But why would such an achievement like Man’s first steps on the Moon generate such irrational fears in the first place? “Within a society, processes leading to change include invention and culture loss,” writes Dr. Dennis O’Neil, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, at the Palomar College, Calif. “Inventions may be either technological or ideological. Culture loss is an inevitable result of old cultural patterns being replaced by new ones … Within a society, processes that result in the resistance to change include habit and the integration of culture traits. Older people, in particular, are often reticent to replace their comfortable, long familiar cultural patterns. Habitual behavior provides emotional security in a threatening world of change. Religion also often provides strong moral justification and support for maintaining traditional ways.”

With the exception of space and science fiction advocates, the overall fear, bewilderment, and confusion about Man’s first steps on the Moon in July 1969 that were experienced by a part of the general public at the time left it viewing the Apollo program not so much as an ongoing epic journey into the Universe, but rather as an exciting and thrilling spectacle similar to a Super Bowl or a baseball game on TV, which had a definite expiry date. By the time Apollo 12 lifted off for the Moon in November 1969, public interest toward the Apollo program was on a steeply declining trajectory. For many, going to the Moon suddenly seemed as “yesterday’s news”—trite and commonplace. Partly reacting to this apathy by the public toward the Apollo missions in the wake of Apollo 11’s success, the Nixon administration gradually cancelled the last three scheduled flights of the Apollo program in the months that followed. The crew of Apollo 17 would be the last humans to date to walk on the soft lunar regolith, in December 1972.

The space shuttle era that followed the Apollo missions would strengthen this view of spaceflight as something routine, due in large to NASA’s own marketing of the space shuttle as a cheap, safe, and reliable mode of regular space transportation. This supposedly routine access to space of the new reusable spacecraft, coupled with its perceived as mundane and uninspiring missions to low-Earth orbit contrary to the Apollo missions to the Moon, further intensified the public’s loss of interest toward spaceflight, making it seem like a dull “truck service” to space. According to Dr. Fabienne Goux Baudiment, Coordinator, MS in Strategic Foresight and Innovation, at the University of Angers, France, this process of linking space exploration primarily with mundane down-to-Earth activities has separated it from its most important dimension, which is to evoke a spiritual sense of wonder. “And thus has happened the Big Mistake: the trivialization of space,” she comments in her essay “When space exploration drives to grandeur.” “In order to justify ongoing space policy and its correlative expenditures in a period of economic crisis … the mainstream idea is to re-assure people: utilitarianism is the new legitimization of the space activities. Thanks to the explosion of the market of telecommunication, space activities are now just ‘industrialized’: a successful rocket launch no longer even appears in the newspapers. Transforming space exploration in banal Earth-centred activities and showing an amazing inability to meet the announced deadlines in the main outer space-oriented projects, [space agencies] have ‘killed’ what was the unique mighty fuel for space exploration: a substratum for myth. For space is a place for gods and heroes, whatever the culture, whatever the religion. And it is as inherent to our imagination as supernatural forces are. That is why people are not interested by its trivialization, but by its magnification. And there, NASA’s policy has been much clever than ESA’s, emphasising pedagogical and cultural approaches to space.”

Spaceflight as blasphemy

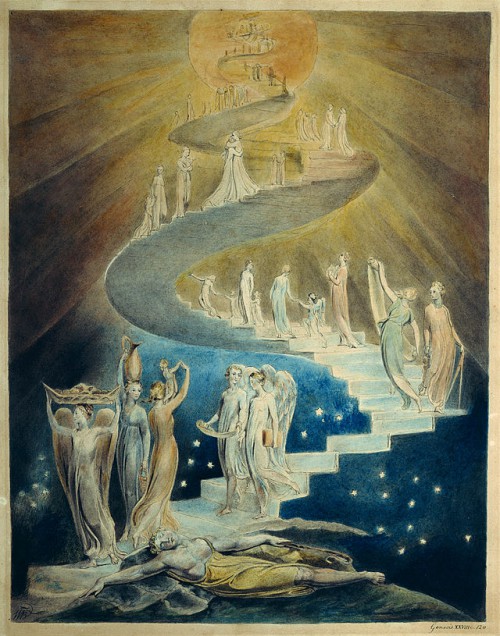

Ever since humans first walked upright and became self-conscious, they gazed up at the night sky, only to be confronted with a realm that was full of mystery and wonder. Most of human cultures throughout history have tried to make sense of the heavens above through religious myth and the belief in the supernatural. The sky was the abode of the gods and mythic heroes, and the final resting place of kings and pharaohs. For most religious traditions, the heavens were also representative of the infinite perfection of god: pure, untainted, and completely separate from the material world, which was perceived as imperfect, flawed, and inherently impure. Most of human history has been characterized by Man’s struggle to bridge these two separate realms, mostly through his struggle for spiritual ascension and subsequent communion with god, as represented by the religious myth of Jacob’s Ladder in the Hebrew Bible. Yet, at the same time, Man’s attempts to climb the heavens have also been portrayed as an act of pride and arrogance and a blasphemy against god, as portrayed in the story of the Tower of Babel.

A similar dualistic approach toward the concept of human spaceflight developed during the 20th century between scientists and theologians, long before the first humans had ever escaped the bonds of Earth. At a time when other science fiction writers envisioned space travel as a modern-day technological version of Jacob’s spiritual ascent to the heavens, others saw it as nothing less than a modern-day Tower of Babel. For the latter, their opposition stemmed from a strong clash between their own deep-seated religious or spiritual beliefs about Man’s place in the Universe and the new reality that was unfolding before their eyes.

One such notable religious opponent of space travel during that period was renowned British scholar and novelist C.S. Lewis, better known for his children book series “The Chronicles of Narnia.” In his “Space Trilogy” series of novels, which was published between 1938 and 1945, Lewis expressed his Christian-inspired objections toward the prospect of human spaceflight that was popularized at the time through the science fiction genre, which he personally viewed as heresy. “What immediately spurred me to write was Olaf Stapledon’s ‘Last and First Men’ and an essay in J.B.S. Haldane’s Possible Worlds’ both of which seemed to take the idea of such [space] travel seriously and to have the desperately immoral outlook which I try to pillory in Weston [the hero of the first book in the Space Trilogy],” stated Lewis in a letter to a personal friend. “I like the whole interplanetary ideas as a mythology and simply wished to conquer for my own Christian point of view what has always hitherto been used by the opposite side.” “In the second book of his Space Trilogy, titled ‘Perelandra’, Lewis made references to the ‘vast astronomical distances which were part of a quarantine that was imposed to us by God’,” comments Greek space historian and writer Thanassis Vembos, in his book “The Ghosts of Space.” “He believed that God wanted Man to be forever bound to the Earth, and that any attempts on Man’s part to leave it, were tantamount to blasphemy … Lewis was outraged with the prospect of human colonization of the Universe and that having ravaged the Earth, humanity was aiming to ravage the rest of the Universe as well.” It is also interesting to note that this fervent debate between scientists and theologians was heated enough as to catch Hollywood’s attention as well. In the classic 1955 science fiction movie “Conquest of Space,” the commander of a space mission to Mars readily proclaims that “the Biblical limitations of Man’s wanderings are set down as being the four corners of the Earth. Not Mars or Jupiter or Infinity … We are invaders … of the sacred domain of God … his heavens. To Man, God gave the Earth. Nothing else. But this taking of … of other planets … it’s almost Iike an act of blasphemy.”

In a modern age that is increasingly dependent on space technology, it may be tempting to view such beliefs as cultural anachronisms, but evidence seems to suggest that these views are nevertheless shared by a large portion of the pubic today. A pilot questionnaire study that was undertaken in 2003 among students at religious colleges and secular universities in the U.S. found that most of the students that had stronger religious beliefs tended to reject various advanced technological concepts like cryogenic freezing, cloning, and personality uploading to distant planets—more than those who had more secular views. When at the conclusion of the study participants were asked to submit their comments, those that were more religious-inclined expressed a general lack of support for such advanced technologies, as well as space travel in particular. “This pilot study indicates that especially religious people may indeed be substantially more likely than other people to reject various forms of technological transcendence,” concludes Dr. William Bainbridge, an Adjunct Professor with the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the George Mason University in Virginia and author of the study. “Some religious respondents felt that technology violates God’s plan for us. That would be bad, not only because it defies the Lord -as they see it- but also because they believe that all human life gains its meaning from God’s plan. ‘Cryonic freezing is something I disagree with; God put us on this Earth at a certain time for a certain reason’. On the same topic others wrote: ‘We as humans do not have the right to play God in such a manner. I don’t believe in altering God’s plan; You are messing with God’s work and his plan for you’. The same objection was leveled against interstellar colonization: ‘Other planets are not made for humans to live on. If God wanted us to live on those planets, he would have put us there’.”

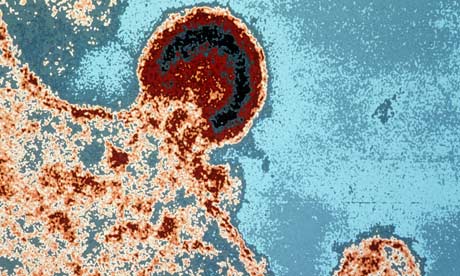

By excluding God from the equation, according to Vembos, we’re still left with a similar ideology, albeit masqueraded as a secular one: that of radical environmentalism. A past AmericaSpace article had explored the irrational, anti-humanist themes behind radical environmentalism in more detail, and the intent is not to repeat this analysis here. Yet it is worth mentioning that at their core, both religious fundamentalism and radical environmentalism have the same ideological underpinnings. “Even without realizing it, environmentalism is recasting ancient Biblical messages to a new secular vocabulary,” writes Dr. Robert Nelson, Professor of Environmental Policy at the University of Maryland. “Environmentalists see humans engaged in acts of vast hubris, remaking the future ecosystems of the Earth. By playing ‘God’ with the Earth, humans seek to become as God themselves.” This type of thinking, which is widespread among the public, academia, and the government alike, also sees Man’s expansion into space as another form of hubris that must be absolutely curtailed, in order to best preserve the Solar System’s pristine environments from the destructive nature of Man. “In all this there is an obvious Biblical quality,” comments Nelson. “It is the story, although now offered in a new secular dress, of human beings created in harmony with the world; tempted into evil; spreading corruption and depravity; and now facing disaster and perhaps the end of the world. There is here a distinctly Calvinist flavor. The sins of mankind are overwhelmingly large; as a founder of Greenpeace, Tom Watson has said, human beings are the ‘AIDS of the Earth’. The roles of reason and natural law are limited; in fact, for many environmentalists it is precisely our attempt to understand nature through rational scientific inquiry that is a prime cause of our current plight. The end of the world is near at hand; the only hope to be saved is a great moral awakening across the land.”

As modern psychology has shown, our decisions are largely based on a set of emotions and core belief systems that for the most part remain subconscious. If, for example, spaceflight is a notion that conflicts with one’s personal belief system, he or she will tend to be less receptive to the idea of providing more funding or support for the space program. “Our shared assumptions operate at an unconscious level,” concludes a NASA-mandated study by the Center for Cultural Studies & Analysis, in Philadelphia, Penn., titled “American Perception of Space exploration.” “Since the cultural beliefs that drive our choices operate below our conscious horizon, it is the almost invisible nature of culture that leads us to believe that we don’t have any, just as you aren’t conscious of your own accent. Therefore, culture is rarely articulated in words, but instead is expressed in behavior. Our ingrained assumptions about how things should be are what set us apart from other cultures. They drive our choices in everything from public policy and our social agenda to the everyday consumer choices we make, from the vision of space exploration down to which brand of toothpaste we choose.” Seen in this light, space policy is much more dependent on our own internal beliefs and views of the world around us, than on external geopolitical or financial factors.

Man has always stood with one foot on the Earth and one in the sky, in his struggle to overcome the perceived imperfectness of the material world and transcend toward the heavens. It is this struggle that has given rise to the drama of the human condition throughout history. Man’s technological ascent toward the sky to walk within the third dimension of space has proved to be not less difficult and challenging than the spiritual pursuit for self-attainment and transcendence of religious and spiritual traditions. Forty-five years ago we took that first decisive “small step” toward that goal.

When will we take the next?

Video Credit: Callum C. J. Sutherland

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Bravo Leonidas, Bravo! This series which you have so artfully created has unequivocally, irrevocably raised you from an intelligent, enthusiastic beginning writer to the level of a skilled, dedicated, exceptionally gifted professional writer. You have, without question, earned the right to hold your head high as an equal to any writer in the spaceflight genre. Heartfelt congratulations my friend, you have truly arrived!

Reading your comments Karol, always makes me wanna fly to the Moon from joy! Commentary such as yours is always the highest reward for me, showing me that I’m writing something that is meaningful and worthwhile. I’m deeply humbled and honored. Thank you!

This out’ta Africa stuff may explane where Europeans came-from, but not human-beings.

I had to respond to this philosoply with an answer rooted n reality. Facbook.com/SullivansProjects.

Great article Leonidas. As a basically religious (but pro-space) sort myself, I would add another (I hope) interesting thought.

The late Michael Crichton, himself an agnostic, once said that he had come to believe that humans had a “religious gene”. That is with conventional religion taken away from them by current society they were impelled to invent an equivalent and that was environmentalism, which returned to all the verities of fundamentalist religion but with secular rationales.

At just the point when many mainstream religious institutions came to accept space as part of “the world” and thus the human domain, along comes environmentalism to try to remove it again, with of course supposedly secular reasons.

Very insightful observation Joe!

Indeed, there’s a saying that ‘even if God didn’t exist, we would have to invent him’. Man is a species that seeks a purpose and meaning in this Universe. I guess that this is the nature of intelligence itself. Others find it through religion, others, like myself, find it through more secular roads.

And spaceflight is in its core a deeply spiritual quest, whether somene is religious or not. It would be funny if it wasn’t tragic, that as you point out, at a time when religious institutions more and more embrace space exploration, there are those (aka radical environmentalists) who want to return us to an intellectual Stone Age. The more I study their philosophy, the more I despise these groups.

Jordan Bassior has a similar essay, The Fear of Boundlessness, in which he discusses the Mundane SF movement and its presentation of itself as “putting away childish things” and bringing science fiction back to realistic limits as being in fact a resurgence of the old notion of “the heavens and the earth” in which the earth was the realm of mundane activities, of ordinary mater, while the heavens were transcendent, the place of the quintessence.

I haven’t read Bassior’s essay Leigh, but thank you for mentioning it, I’ll have to look it up.

Indeed, that is the ‘gospel’ which dominates today’s zeitgeist: that we should be ‘realists’, while limiting ourselves more on our Home planet. Spaceflight is a naïveté and Man should remain earthbound forever because we have no business ‘out there’.

This type of thinking is the epitome of intellectual decline and decadence in my opinion.