Thirty years ago, yesterday, on 27 August 1984, one of the most momentous—and, as circumstances would transpire, also tragic—events in space history unfolded, when President Ronald Reagan announced the Teacher in Space Project (TISP) and directed NASA to find a gifted educator with the ability to communicate his or her enthusiasm to ground-based students from the orbiting shuttle. Over the course of the following months, more than 11,000 U.S. teachers applied and were assessed, culminating in July 1985 with the selection of Christa McAuliffe, a social studies educator from Concord, N.H. Her fateful launch aboard Challenger on Mission 51L on 28 January 1986 brought the shuttle program to its knees, but the spirit of McAuliffe’s unrealized voyage endured and finally came to pass in August 2007, when her backup, Barbara Morgan, flew as a fully-fledged mission specialist on STS-118.

From the outset, NASA had presented the shuttle as a vehicle capable of carrying not only professional astronauts, scientists, and engineers into orbit, but also eventually civilians, and by 1984 the need to make good on that pledge became apparent. Explorers, journalists, and entertainers had been considered, as the space agency pondered which profession might yield “the best” private citizen to send aloft on the pioneering first mission. Ultimately, the decision settled on a teacher. Dick Scobee, who commanded Mission 51L, agreed that it was the right decision. “Teachers teach the lives of every kid in this country through the school system and if you can enthuse the teachers about doing this, then you enthuse the students and impress on them that’s something to expect in their lifetime,” he said in one of his last interviews. “Man needs to explore and that’s part of the thing we have to do to ensure our future. So as far as I’m concerned, it’s a good insurance policy for the human race.”

The woman upon whom fate would both smile and scowl was born Sharon Christa Corrigan in Boston, Mass., on 2 September 1948. She was the eldest of five children of accountant Edward Corrigan and teacher Grace Corrigan, with an ancestry which included Irish, Lebanese, German, English, and Native American. After high school in Framington, the young girl developed a fascination with the space program—even telling one of her classmates in the wake of John Glenn’s orbital mission that someday people would journey to the Moon and beyond—and entered Framington State College to study education and history. She received her degree in 1970 and, within weeks, married her long-term boyfriend, Steven McAuliffe.

The couple moved closer to Washington, D.C., to allow him to attend law school, and Christa McAuliffe found work as an American history teacher at Benjamin Foulois Junior High School in Morningside, Md. She next moved to Thomas Johnson Middle School in Lanham, Md., teaching history and civics, where she remained until 1978. During this period, McAuliffe completed a master’s degree in education supervision and administration at Bowie State University and she and her husband moved to Concord, N.H., where Steve accepted a post as assistant to the New Hampshire Attorney-General. By 1982, Christa began teaching American history, law, and economics—together with a self-designed course, “The American Woman”—at Concord High School.

Following President Reagan’s announcement in August 1984, McAuliffe duly applied for the Teacher in Space Project. The non-profit Council of Chief State School Officers was selected by NASA to co-ordinate the selection process and from November 1984 until February 1985 more than 11,000 applications were submitted. These were winnowed down to 114 semi-finalists by state, territorial, and agency review panels and McAuliffe was one of only two teachers to be nominated in New Hampshire. In her application, she wrote: “I cannot join the space program and restart my life as an astronaut, but this opportunity to connect my abilities as an educator with my interests in history and space is a unique opportunity to fulfil my early fantasies. I watched the space program being born and I would like to participate.” A judging panel, including former astronauts, university presidents, actress Pam Dawber, former basketball player Wes Unseld, and Robert Jarvik, inventor of the artificial heart, presided over these candidates at interview and eventually narrowed the list to just 10 finalists.

On 26 June 1985, at the White House, President Reagan could not resist bringing his irrepressible humor to the proceedings when he presented the finalists to the press. “Whichever one of you is chosen might also want to take under consideration the opinion of another expert: The acceleration which must result from the use of rockets inevitably would damage the brain,” he told them, “so consider yourself forewarned!” Little could he possibly have known that such dire predictions would come awfully true for the Teacher in Space in January of the following year.

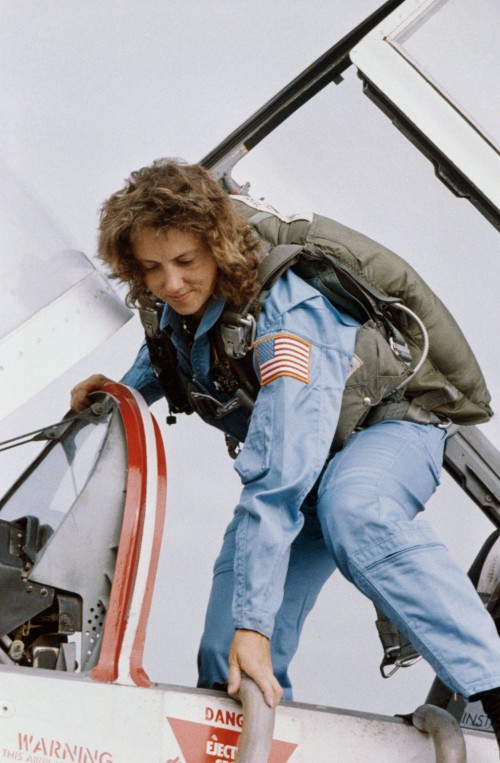

Finally, on 18 July, Vice President George H.W. Bush named McAuliffe as the prime candidate, backed up by McCall, Idaho, elementary school teacher Barbara Morgan. NASA psychiatrist Terry McGuire told New Woman magazine that McAuliffe was the most “balanced” of the 10 finalists, whilst other senior officials found that her endearing manner and infectious enthusiasm set her apart from the others. Her 100-hour training program at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, began in September, with launch aboard Mission 51L targeted for late December.

The planned six-day flight had changed considerably since the selection of its “core” NASA crew—Commander Dick Scobee, Pilot Mike Smith, and Mission Specialists Ellison Onizuka, Judy Resnik, and Ron McNair—in January 1985. Originally, they were targeted to launch in November aboard shuttle Atlantis to deploy NASA’s third Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS), as well as one of the commercial satellites (either Palapa-B2 or Westar-VI) recently retrieved by the 51A crew. As 1985 wore on, their payload manifest morphed, and by March they were listed on Mission 61C in December to deploy a pair of commercial satellites atop Payload Assist Module (PAM) boosters and perform a pair of EVAs to operate an experimental Space Station structure. By the early fall, they had been redesignated to Mission 51L, carrying the TDRS-B payload and the Spartan-203 astronomy satellite to perform observations of Halley’s Comet.

As important as 51L’s primary payloads were, in the eyes of the press and the public it was McAuliffe’s intended activities which drew the most attention. She was to teach from space, providing a much-needed publicity boost for NASA as it sought to demonstrate that its reusable fleet of orbiters were truly the spacefaring equivalents of commercial airliners and convince senior lawmakers to support a permanent Space Station. Years later, McAuliffe’s mother insisted that the general atmosphere in the weeks leading up to Challenger’s fateful launch was that the shuttle was far safer than an airliner, simply due to the high number of precautions taken by NASA. Even McAuliffe herself had expressed confidence that her only “fear” was a failure of the orbiter’s toilet.

Her tasks included a pair of 15-minute lessons: the first, entitled “The Ultimate Field Trip,” was a guided tour of the shuttle to familiarize students with on-board living and working conditions, while the second, called “Where We’ve Been, Where We’re Going,” focused on NASA’s plans for the Space Station. Both were to have been aired by PBS on 2 February 1986, the last full day of Mission 51L, and McAuliffe would have explained the roles of her six crewmates, identified and summarized the experiments aboard Challenger, and enthused her students with a vision of the future.

“I think it’s going to be very exciting for kids to be able to turn on the TV and see the teacher teaching from space,” she said in one of her last interviews. “I’m hoping that this is going to elevate the teaching profession in the eyes of the public and of those potential teachers out there. Hopefully, one of the secondary objectives of this is students are going to be looking at me and perhaps thinking of going into teaching as professions.”

McAuliffe and fellow payload specialist Greg Jarvis, representing Hughes Aircraft, joined the 51L crew relatively late in their training process. Yet both were quickly accepted and grew to become highly respected members of the team. “It’s refreshing to have somebody on board that’s really dedicated and enjoys doing what they’re doing,” Dick Scobee remarked, “but also she goes into the training with a positive attitude and stays out of the way when she needs to stay out of the way, she gets involved when she needs to get involved and does basically all the right things, and so does Greg Jarvis. Both of them, from our standpoint, are good payload specialists. They came aboard with a good, open mind, they’re accommodating to our system, we try to be accommodating to theirs and it’s a nice tradeoff.”

As the world reflects on the 30th anniversary of the unveiling of the Teacher in Space Program, it is difficult not to be struck by the lost opportunity of Christa McAuliffe achieving orbit and sharing her passion and her excitement with students on the ground. Yet her legacy endures to this day, with honors, scholarships, and prizes in her name. In July 2004, in the aftermath of the second shuttle disaster, McAuliffe and the 51L and STS-107 crews were recognized by President George W. Bush with the Congressional Space Medal of Honor. By that time, her backup, Barbara Morgan, was already training to fly shuttle mission STS-118 and in that same year, 2004, three other educators—Joe Acaba, Ricky Arnold, and Dottie Metcalf-Lindenburger—had been selected for astronaut training. All three would ride shuttles and journey to the International Space Station (ISS) later in the decade.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace