“Here comes the criminal,” joked Joe Kerwin, one day in October 1977, when a candidate named Jeffrey Alan Hoffman appeared at the Astronaut Selection Panel at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas. Before the panel, which also included Chief Astronaut John Young and Director of Flight Crew Operations George Abbey, was a tall, bearded civilian astronomer, who would come to be described variously as the stereotypical professor and a pure scientist, yet who would carve out a niche for himself by becoming the first human being to exceed 1,000 hours of flight time on the shuttle. In fact, by the end of his career, Hoffman—who turns 70 today (Sunday, 2 November)—would have performed the shuttle program’s first unplanned EVA and supported three dramatic spacewalks to repair and service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST).

Bearded, riding a collapsible bicycle, and carrying a lunch pail in hand were three attributes of Hoffman remembered by his contemporary, astronaut Mike Mullane, writing years later in his memoir, Riding Rockets. “To the very end,” Mullane wrote, “Jeff remained an unpolluted scientist.” Yet his life had encompassed far more than academia; he was a skydiver, an accomplished mountaineer, and a skilled engineer. He came from Brooklyn, N.Y., where he was born into a Jewish family of physicians on 2 November 1944.

“My parents took me all over the place to museums and concerts,” Hoffman reflected in his NASA oral history, “and among the other places was the Hayden Planetarium.” This quickly hooked the young boy on astronomy. He received his schooling in Scarsdale and entered Amherst College in Massachusetts to study astronomy, graduating summa cum laude in 1966. He went to Harvard for his doctorate, which he received in 1971. His research focused on high-energy astrophysics, specifically cosmic gamma rays and X-rays, and he participated in the design, construction, testing, and flight operations of a balloon-borne, low-energy gamma ray telescope.

Years later, Hoffman strongly believed that this probably attracted him to NASA and vice versa. “I did a lot of work with my hands,” he said, “building electronics, machining stuff. That probably stood me in good stead with NASA, because when they’re selecting astronauts, they want people who know how to work in a lab, who can fix things and build things.” He then moved to England for three years to undertake post-doctoral work at the University of Leicester, serving as project scientist for the medium-energy X-ray experiment on Europe’s Exosat mission. Whilst in England, he met his wife, Barbara, and became a father for the first time. The Hoffmans returned to the United States in 1975 so that he could take up a position at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as the project scientist in charge of the hard X-ray and gamma ray experiment aboard the first High Energy Astronomy Observatory (HEO). “That was probably the most interesting scientific time that I’ve ever spent, because … we discovered a new phenomenon called X-ray bursts,” he recalled. “I guess we wrote about 35-40 papers about it. These are thermonuclear explosions on the surface of a neutron star; pretty wild stuff.”

By his own admission, Hoffman had been drawn to astronomy and astrophysics through his fascination for space exploration, although the opportunity to do such things himself seemed out of reach. “The early astronauts were all military test pilots,” he pointed out. “I was never particularly interested in that career. In fact, I wasn’t particularly interested in airplanes, because they didn’t go high enough or fast enough. I always liked rocket ships.” The chance finally came in October 1977, when he was invited to Houston for a week of interviews and testing. At first, his wife thought he was joking when he told her about the astronaut application. It came as a shock to Hoffman that it spelled the end of his research career in astrophysics. “NASA made it very clear that they were not looking for people to come and be research astronomers,” he explained. “They were looking for astronauts who had to be generalists, because there were a lot of different things we were going to have to learn how to do.” It was disappointing, but it marked a change in Hoffman’s career.

“The most unusual thing about my application,” he continued, was that “I very well could have been the only person who was selected as an astronaut, who admitted in their application to having been convicted of a crime.” It had happened during his tenure in Leicester, when he and some friends took a converted coastal steamer across the North Sea to explore the Norwegian fjords. Unfortunately, the original captain of the trip canceled at the last minute and Hoffman—despite lacking the proper certification—stepped in. Upon their return, the coast guard arrested them and slapped a £10 fine, which Hoffman’s friend disputed. The case was upheld because not only did Hoffman lack the required certification to captain a British flagged vessel, it was also necessary to hold British citizenship. At the time, Hoffman did not have this and the party were convicted.

“We actually had to go to Crown Court,” he told the NASA oral historian, “with the wigs and the whole deal.” They were fined £250 and when Hoffman came to fill in his NASA application form, he hesitated before deciding to be honest and admit to his offense. Surely, NASA would not delve that deeply into his past. They did. Nor could the selection board prevent themselves from making light of the situation. At his interview in Houston, the first greeting from panel member Joe Kerwin—a veteran of the first manned mission to Skylab—as Hoffman walked into the room was: “Here comes the criminal!”

This appearance was made complete by a beard, which Hoffman quickly needed to remove. “As soon as I got to the altitude chamber in preparation for T-38 flying, it became pretty clear that you can’t make a good face seal with a full beard, so off came the beard. My wife shrieked when I walked through the door!” (He kept a moustache, however, through the remainder of his 19-year astronaut career.)

In September 1983, Hoffman was selected as a mission specialist for a flight whose twists and turns of good and ill fortune saw its payload changed repeatedly, delayed firstly by the shuttle program’s first pad abort and later by problems with the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS). At length, the crew launched in April 1985, giving Hoffman his first glimpse of the Home Planet from space. “That’s when it really hit me,” he said. “I floated over and I looked out the window and there was the Earth going by. You could see Africa off in the distance. Then I looked in the mirror and there was me in space. I just got this big ear-to-ear grin and I just couldn’t stop smiling for several hours! It was just such an elation.”

Mission 51D launched two communications satellites—one for Canada and a second, Syncom 4-3, on behalf of the U.S. Navy—but it was the latter which caused a major headache, when its deployment switch failed and an unplanned EVA, involving Hoffman and crewmate Dave Griggs, was executed to utilize a makeshift fly swatter to activate it. The two men had undertaken more than 50 hours of mission-specific EVA training, but did not anticipate being called upon to perform a spacewalk. In fact, prior to launch, they joked with the staff at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala., that if an EVA was required, the shuttle crew would buy the beer. It would be worth it.

Although the 3.5-hour EVA was ultimately unsuccessful in reactivating the stranded satellite, Syncom 4-3 was visited by another shuttle crew, later in 1985, repaired and delivered into its correct orbit. By this time, Hoffman had already been assigned to his second flight, Mission 61E, which was planned for March 1986 with the ASTRO-1 payload to make astronomical observations and study Halley’s Comet. Original plans called for three ASTRO missions between March 1986 and July 1987, with Hoffman expected to fly all three. The ASTRO-1 flight was five weeks away from launch, when Challenger catastrophically exploded in January 1986 and the entire shuttle program was brought to its knees. During the lengthy down time, Hoffman pursued a master’s degree in materials science at Rice University, before being named in November 1988 to the “new” ASTRO-1 mission, designated STS-35. Whilst training for this flight, he was also assigned as payload commander for STS-46, a double-deployment mission for the Tethered Satellite System (TSS) and the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA). The Italian-built TSS project had been brought to Hoffman’s attention in 1987 by European astronaut Claude Nicollier, with whom he later flew on three shuttle missions.

However, STS-35 fell victim to a series of hydrogen leaks in the summer of 1990. At one stage, the delays became so severe that they affected the crew’s children. Prior to one launch attempt in September, rather than risk taking them out of school for a long period, several of the astronauts paid for air tickets from Houston to Florida and asked neighbors to drive the children to the airport. Hoffman’s children, aged 11 and 15 at the time, were seated aboard an aircraft, with one engine in the process of starting up, when the departures desk received a call from the astronaut himself. Another hydrogen leak had appeared in the shuttle, the launch had been delayed and the Hoffman children were hurriedly removed from the aircraft and returned home.

In total, STS-35 was delayed by seven months, but eventually flew in December 1990, returning a vast quantity of data from three ultraviolet telescopes and one X-ray telescope aboard the shuttle. In spite of computer problems and pointing system failures, ASTRO-1 was highly successful—so successful, in fact, that in May 1991 NASA decided to fund a reflight of the ultraviolet telescopes. In the meantime, Hoffman flew his third mission in July 1992, although the TSS effort was troubled when its tether jammed and instead of deploying to a distance of 12 miles (20 km), it actually managed only about 840 feet (256 meters). Meanwhile, the EURECA satellite, deployed by means of the shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), was successfully placed into orbit.

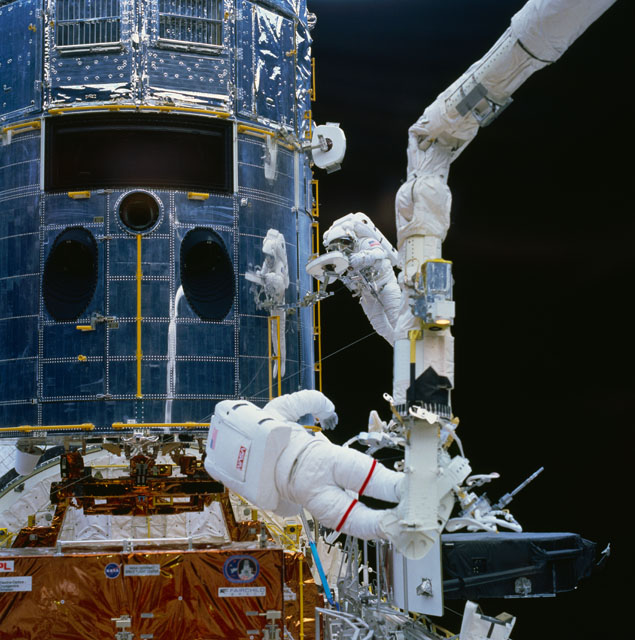

Within weeks of returning from STS-46, Hoffman was appointed as one of four EVA crew members for STS-61, the long-awaited servicing and repair mission to the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). NASA required astronauts with prior EVA expertise to participate in the flight and Hoffman’s unplanned spacewalk from Mission 51D made him one of very few active members of the corps at the time to hold such skills. In December 1993, he and Story Musgrave performed three of STS-61’s five total spacewalks. Despite struggling with warped instrument bay doors, a bent solar array strut, and other troubles, the crew completed one of the most spectacular shuttle missions in history, fitting new corrective optics and new instruments to transform HST from a white elephant of late-night chat shows into a white knight for astronomical discovery. The entire crew and their support teams later won the coveted Collier Trophy in 1994 for their efforts.

Hoffman’s fifth and last flight came in February 1996, when he served aboard a reflight of the TSS mission on STS-75. Although the satellite deployed to its full length, and satisfactory electrodynamic data was gathered, the tether snapped and TSS began drifting away into space. Elsewhere, the crew—which included three of Hoffman’s former crewmates from STS-46—tended to microgravity and other experiments. On 29 February, seven days into the flight, Hoffman became the first human to exceed 1,000 hours of cumulative time aboard the shuttle. By the time he returned to Earth on 9 March, he would have accrued no less than 1,211 hours (more than 50 days) in space, across his career. Added to this, Hoffman had spent more than 25 hours spacewalking on four EVAs.

Although Hoffman departed the astronaut corps in July 1997, to become NASA’s European representative in Paris, France, there existed the very real possibility of a sixth flight. In his oral history, he explained that he was interested in a long-duration mission to Russia’s Mir space station, although he did not fit the Soyuz. “It wasn’t just my height,” he said. “There’s all sorts of anthropometric measurements: your thigh height, your sitting height, your chest diameter. I failed a few of those.”

His spacewalking experience, though, led then-JSC Director George Abbey to approach him with another shuttle flight opportunity. Hoffman, however, was interested in the European representative post and he asked Abbey to hold off on the mission assignment. “There was a long silence,” he said, “as only people who know George Abbey can totally appreciate, as he pondered that.” At length, Abbey agreed that Hoffman would be a good fit for the European role. He served in Paris for four years, until July 2001, after which he was seconded to MIT as a professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. He still works for the department and currently serves as Professor of the Practice and Director of the Massachusetts Space Grant Consortium.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace