Ironically, the spacecraft from which the most Extravehicular Activities (EVAs) were performed—the space shuttle—was not originally intended to carry the capability for spacewalking at all. “The NASA perspective of a shuttle was an airliner,” explained space suit engineer Jim McBarron in an oral history, “and the people inside it wouldn’t need suits.” It was only through prompting and questioning of senior management, when faced with the need to have a contingency capability to close the orbiter’s payload bay doors, that an EVA requirement was implemented. From the first spacewalk conducted outside the shuttle in April 1983 until the last in July 2011, 163 discrete EVAs have seen astronauts from the United States, Russia, Japan, Switzerland, Canada, France, Sweden, and Germany test jet-propelled backpacks, salvage and repair satellites and space telescopes, deploy and retrieve experiments, and build the International Space Station (ISS).

As described in yesterday’s AmericaSpace article, substantial advances in EVA techniques and technologies had already been accomplished before the first shuttle mission got underway in April 1981. Notably, 12 men had walked on the Moon, three had walked in “cislunar space,” and one had performed a Stand-Up EVA (SEVA) to gain a 360-degree perspective of his landing site. Astronauts had evaluated their locomotion in the peculiar microgravity environment, and, aboard Skylab, they had demonstrated that they could embark on complex tasks to save entire missions. With the advent of the shuttle era, EVA was expected to take center-stage, and, in mid-1982, NASA announced plans for an ambitious mission to retrieve, repair, and deploy back into orbit the damaged Solar Maximum Mission (SMM or “Solar Max”) observatory in early 1984.

On STS-5 in November 1982, the fifth flight of Shuttle Columbia, it was intended that an almost nine-year hiatus in U.S. spacewalking activity would come to an end with a 3.5-hour EVA by astronauts Bill Lenoir and Joe Allen. In addition to testing the new shuttle-specification space suits and rehearsing techniques for manually closing the payload bay doors, they would have tested tools for the Solar Max repair, including fixed and torsion-adjustable bolts, a special wrench, and a dummy Main Electronics Box (MEB) for the satellite’s coronagraph. Unfortunately, the EVA was postponed by 24 hours, when Lenoir and STS-5 Pilot Bob Overmyer suffered a severe bout of space sickness, and an attempt to perform the spacewalk the following day came to nothing when a problem was encountered with a ventilation fan on one of the suits and a pressure shortfall in the primary oxygen regulator of the other suit. Several of the helmet-mounted floodlights also failed to operate correctly, and, following fruitless attempts to troubleshoot the problems, the EVA was canceled and subsequently rescheduled for the next mission, STS-6.

“I guess I was the bad guy,” STS-5 Commander Vance Brand told the NASA oral historian. “I recommended to the ground that we [cancel] the EVA, because we had a unit in each space suit fail in the same way. It looked like we had a generic failure there. It was the first time out of the ship. We didn’t want to get two guys—or even one guy—outside and then have [another failure]. We could have taken a chance and done it, but we didn’t. I’m not sure Bill Lenoir was ever very happy about that, because he and Joe, of course, wanted to go out and have that first EVA.”

In December 1982, NASA announced that the EVA would be attempted by astronauts Story Musgrave and Don Peterson on STS-6, the maiden voyage of Shuttle Challenger, which eventually launched in April 1983. “It didn’t give us much time to train,” Peterson recalled in his NASA oral history. “I didn’t have much experience in the suit, but the advantage we had was that Story was the astronaut office’s point of contact for the suit development, so he knew everything there was to know. He’d spent 400 hours in the water tank, so he didn’t really have to be trained!” By his own admission, Peterson’s EVA training for STS-6 “was pretty rushed.” He recalled being underwater in the Weightless Environment Training Facility (WET-F) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, on 15-20 occasions, “and that’s not really enough to know everything you need to know.”

Unlike previous Apollo space suits, the modularized shuttle ensemble, with its waist closure ring, eliminated the need for pressure-sealing zips and therefore had a much longer shelf life. Additionally, the use of newer, stronger, and more durable fabrics enabled space suit engineers to design joints with better mobility, resulting in lower weight and a reduction in overall cost. On 6 April 1983, they opened the outer airlock hatch into Challenger’s payload bay and—with Musgrave aged 47 and Peterson aged 49—became the oldest men at that time ever to embark on an EVA.

During their 4.5 hours outside, the astronauts evaluated their movement, tested the tools to manually close the payload bay doors, and rehearsed procedures for the Solar Max repair. Yet the experience of being disconnected from their spacecraft was profound. “You remember little things like sound,” Musgrave told a post-flight press conference. “Even though there’s a vacuum in space, if you tap your fingers together, you can hear that sound because you’ve set up a harmonic within the space suit and the sound reverberates within it. I can still ‘hear’ that sound today. But the main impression is visual: seeing the totality of humanity within a single orbit. It’s a history lesson and a geography lesson; a sight like you’ve never seen.”

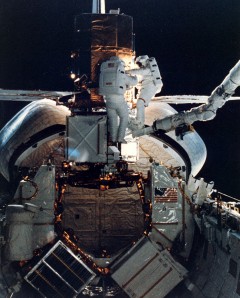

One of the critical elements of the Solar Max was the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), a jet-propelled backpack, developed by Martin Marietta, which would allow spacewalkers to fly “untethered” to great distances from the shuttle. Its first test flight was planned for shuttle Mission 41B in February 1984 and featured astronauts Bruce McCandless—who had played a pivotal role in the development of the MMU—and Bob Stewart flying it as far as 300 feet (90 meters) into the inky blackness. This cleared a significant hurdle for the retrieval and repair of Solar Max in April by the crew of Mission 41C. Despite initial difficulties, spacewalkers George “Pinky” Nelson and James “Ox” van Hoften and their crewmates Bob Crippen, Dick Scobee, and Terry Hart succeeded in capturing and repairing Solar Max and boosted it back into its operational orbit.

As the Americans got back into the business of EVA, the Soviets did likewise. Following the launch of their Salyut 7 space station, cosmonauts Anatoli Berezovoi and Valentin Lebedev performed a spacewalk in July 1982, working with the connection of pipes and girders to practice methods for the augmentation of the solar arrays. This augmentation was to be carried out during a series of EVAs by cosmonauts Vladimir Titov and Gennadi Strekalov, but when they almost lost their lives in a harrowing launch abort in September 1983 the task fell partly to the incumbent Salyut 7 crew of Vladimir Lyakhov and Aleksandr Aleksandrov. On 1 November, the two men ventured outside the station to begin a task for which they had not specifically trained, and, in doing so, Lyakhov became the first Soviet cosmonaut to make a second EVA. During their two hours and 50 minutes outside, the two men carefully attached an auxiliary solar power to one side of Salyut 7’s dorsal array, then unfurled it to its full length of 16 feet (5 meters). Two days later, on 3 November, they were back outside for almost three hours and successfully installed a second auxiliary panel.

The following year, 1984, saw many spacewalking records fall to the Soviets. In a four-week period from 23 May to 19 May, cosmonauts Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov performed no less than five EVAs—an achievement equaled only by U.S. astronaut Dave Scott at that time—to tend to a troublesome propellant leak and further augment Salyut 7’s solar arrays. In doing so, the two men also became the first Soviet cosmonauts to perform in excess of three EVAs. The rate at which these spacewalks were performed necessitated a rapid-fire series of Progress resupply vehicles, three of which were launched in a six-week period, to replenish the oxygen expelled overboard from the airlock.

NASA had already announced plans for Kathy Sullivan to become the first female spacewalker on Mission 41G in October 1984, and it was seen as no coincidence that the Soviets pipped them to the post by launching Svetlana Savitskaya to Salyut 7 in July. Whilst aboard the station, Savitskaya and fellow cosmonaut Vladimir Dzhanibekov spent almost four hours in vacuum, testing a universal hand tool for cutting, welding, soldering, and brazing. Finally, in August, Kizim and Solovyov performed the sixth EVA of their expedition to tend to an oxidizer leak, wrapping up their final spacewalk, after a cumulative 22 hours and 50 minutes outside Salyut 7. They had performed more EVAs than any single astronaut or cosmonaut in history and, in a single flight.

Less than three months after Savitskaya’s voyage, in October 1984, Challenger launched on Mission 41G, one of whose tasks was a 3.5-hour EVA by Dave Leestma and Kathy Sullivan to evaluate hardware for the future refueling of satellites in low-Earth orbit. Mounted at the rear end of the shuttle’s payload bay was the Orbital Refueling System (ORS), containing highly toxic hydrazine, some of which the spacewalkers would transfer between a pair of spherical tanks. Upon venturing outside, Leestma described the experience to Henry S.F. Cooper, Jr., for the 1987 book Before Lift-Off, as “like the difference between sitting at a desk in a big room and sitting at a desk in the middle of a prairie.” After the flight, the surgeons told him that his electrocardiogram reading went exceptionally high. During the course of EVA, six hydrazine transfers were successfully completed.

America’s next spacewalks occurred just a few weeks later, in November, when Mission 51A astronauts Joe Allen and Dale Gardner embarked on the final voyage of the MMU to successfully retrieve the Palapa-B2 and Westar-VI communications satellites and bring them back to Earth for refurbishment and reuse. Both satellites had been launched earlier in the year, but a booster malfunction had left them in lower than intended orbits. In the year prior to the catastrophic loss of Challenger, two other shuttle crews—Mission 51D in April 1985 and Mission 51I in August—were tasked with performing EVAs to repair orbiting communications satellites. Both missions put the skill and ingenuity of astronauts and flight controllers to the test. On Mission 51D, astronauts Jeff Hoffman and Dave Griggs performed the first unplanned EVA of the shuttle era, unsuccessfully attempting to use a makeshift fly swatter to activate a deployment switch on the Syncom 4-3 satellite. Four months later, Mission 51I spacewalkers James “Ox” van Hoften and Bill Fisher executed a pair of spectacular EVAs in which they revived the satellite and sent it back into orbit.

The story behind the 51I spacewalks is an indicator of the seemingly bulletproof attitude that pervaded much of NASA in the months preceding the loss of Challenger. Van Hoften and his 51I crewmate Mike Lounge were both on alert status with the Air National Guard in April 1985, when they learned of the Syncom failure. They immediately started swapping ideas about how to solve it. “Back then,” van Hoften told the oral historian, “there was a much more can-do spirit at NASA and everyone felt like, hey, you can do anything.” The space agency’s management was sufficiently impressed to send the crew to Hughes Aerospace—the satellite’s prime contractor—to lay out their plan. The company’s president was so impressed with van Hoften’s presentation that he immediately called NASA Administrator Jim Beggs to invest $5 million in the salvage effort.

Less than eight weeks before the launch of Challenger on her final, fateful voyage, the crew of Mission 61B performed two EVAs to support the construction of hardware in readiness for NASA’s proposed Space Station. The Experimental Assembly of Structures in EVA (EASE) was an inverted tetrahedron of interconnected tubes, whilst the Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) comprised a 43-foot (13-meter) “tower,” both to be assembled in the shuttle’s payload bay. Following its conception in 1984, the EASE-ACCESS task jumped across several missions on the shuttle manifest, before settling on Mission 61B and being assigned to a pair of first-time spacewalkers named Jerry Ross and Sherwood “Woody” Spring.

Over a period of several months, the two men worked with the EASE-ACCESS team to choreograph a pair of six-hour EVAs to assemble the structures, whilst encased in pressurized space suits. “Both crew members were in fixed foot restraints,” said Ross in a NASA oral history interview, describing the ACCESS assembly task. “It was basically just a matter of bringing a part out, putting it onto this assembly fixture, hooking the components together, rotating to the three faces, then sliding the completed segment of truss up, and repeating the process for a total of 10 ‘bays’. We knew that that technique would be a very satisfactory way of doing business, because when a crew member’s feet are anchored properly, that gives you both hands free to do work.” EASE, on the other hand, was more problematic, since one of the men would be positioned, free-floating, without foot restraints, at the “top” of the structure, holding on with one hand and torquing the beams into position with the other. Lessons from earlier EVAs had already proven that the absence of foot restraints and adequate hand holds made it extremely difficult for spacewalkers to steady themselves and perform tasks. In two highly successful spacewalks on 29 November and 1 December 1985, Ross and Spring triumphantly built the EASE-ACCESS framework.

Returning inside the airlock of Shuttle Atlantis, Ross could hardly have imagined that calamity would soon before the program and that the next U.S. EVA would be more than five years into the future. He could also hardly have known that he would be the next American to perform a spacewalk and, in his wildest dreams, would have struggled to accept that a little over a decade hence, in December 1998, he would be assembling components for the real-life International Space Station (ISS) in orbit.

The concluding parts of this series will appear next weekend.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace