NASA’s Curiosity rover on Mars may have been stealing the spotlight in recent years, but the other rover, Opportunity, is still going strong after 12 long years. Opportunity has survived the harsh environment and various challenges for much longer than anyone anticipated, and now is taking on a new task: climbing slopes as steep as 30 degrees while searching for deposits of clay minerals which had already been detected by orbiting spacecraft. The region where Opportunity landed, Meridiani Planum, is mostly flat plains, but now on the rugged edge of the huge Endeavour crater, the rover is becoming something of a mountain climber.

The steep slopes sound treacherous, but Opportunity can handle it. During two drives in late January, which totalled 31 feet (9.4 meters), the wheels slipped less than 20 percent. The amount of slip is calculated by comparing the distance the rotating wheels would have covered if there were no slippage to the distance actually covered during the drive, based on “visual odometry” imaging of the terrain as the rover drives.

“Opportunity showed us how sure-footed she still is,” said Mars Exploration Rover Project Manager John Callas at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “The wheel slip has been much less than we expected on such steep slopes.”

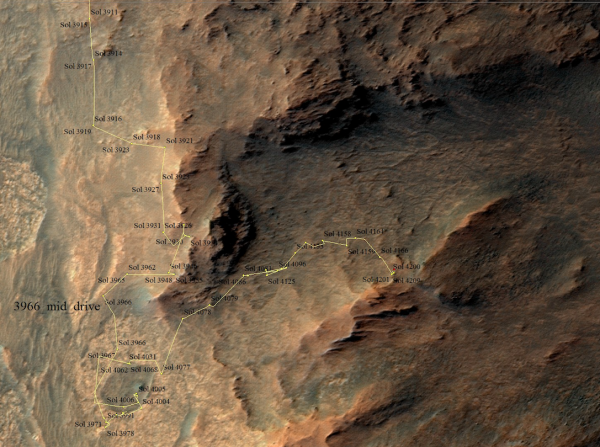

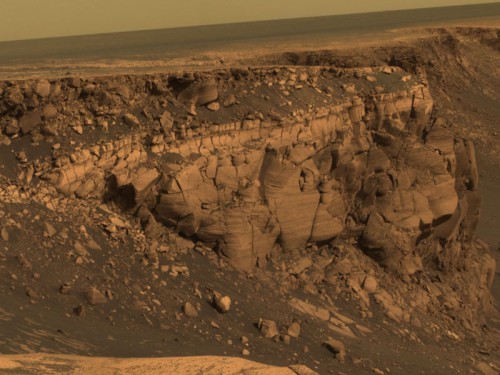

Mission scientists want to get a close-up look at material in “red zones,” which are redder in comparison to the surrounding terrain which is more tan-colored. It is in these zones at a location called Knudsen Ridge that researchers expect to find the clay minerals, which will provide more information about past wetter conditions in this region billions of years ago. Knudsen Ridge is on the southern flank of Marathon Valley which cuts through the rim of Endeavour crater on the western side.

“We’re hoping to take advantage of the steep topography that Mars provides us at Knudsen Ridge to get to a better example of the red zone material,” said Steve Squyres of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., principal investigator for the mission.

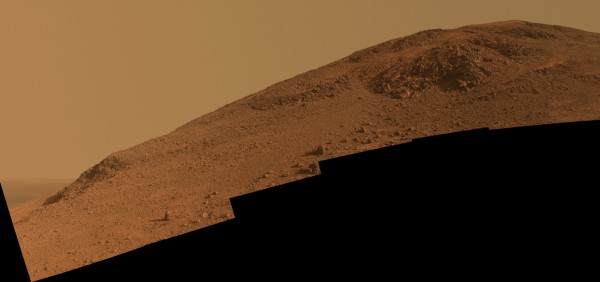

Knuden Ridge is a great look-out point, overlooking the vast floor of Endeavour crater, which is 14 miles (22 kilometers) across. It was named after Danish astrophysicist and planetary scientist Jens Martin Knudsen (1930-2005), who was a founding member of the science team for both Opportunity and its twin rover Spirit, which stopped functioning in 2009.

“This ridge is so spectacular, it seemed like an appropriate place to name for Jens Martin,” Squyres said.

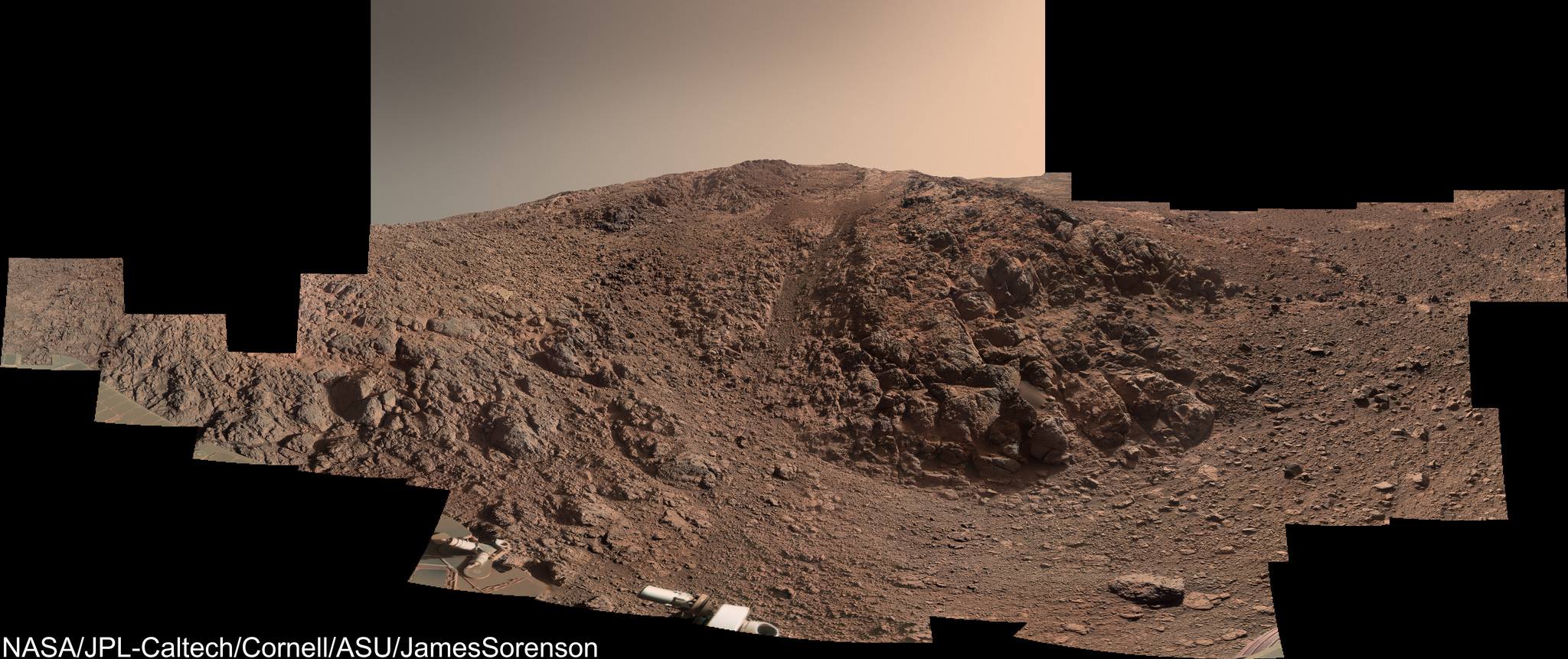

The views from this ridge have been incredible in images sent back by the rover, which first arrived at Marathon Valley area in 2014. The view as seen in the first image combines multiple images taken with the panoramic camera (Pancam) on Oct. 29 and Oct. 30, 2015, during the 4,182nd and 4,183rd Martian sols (days) of the rover’s mission. For much of the mission the rover was on the flat, mostly featureless sandy plains, but stops at places like Endeavour crater and Victoria crater have provided nice changes in the scenery. But for now the attention is mostly on the red zones, which appear to contain the clay minerals the mission team has been looking for.

“The locations of red zones in Marathon Valley correlate closely with the phyllosilicate signature we see from orbit,” Squyres said. “That alone is not a smoking gun. We want to determine what it is about their chemistry that sets them apart and what it could have to do with water.”

Such clay minerals, also known as phyllosilicates, are usually formed in water, which is why scientists are so interested in them. Like the rest of Mars, this region is pretty much bone-dry now, but other evidence from Opportunity has also indicated that there used to be a lot more water here, in the form of playa lakes and groundwater. Most of that water, however, was rather acidic and salty, but clay minerals would indicate water which was more neutral and non-acidic, which would be better suited for possible microbial life-forms, if they ever existed.

As a test of whether water was indeed involved in the creation of the “red zone” material, the chemistry of that material will be analyzed and compared to material from the surrounding, more tan-colored bedrock.

This was not the first time Opportunity went mountain climbing either; the rover had also previously climbed to the summit of Cape Tribulation, which is on the western edge of Endeavour crater and about 4,560 feet (1,390 meters) tall, the highest point on the edge of the crater.

“The view at the summit is spectacular,” according to rover science team member Larry Crumpler, of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science (NMMNHS).

“From here we can see all the way to the other side of the crater, we can see the rim looking north along the path to this location, and we can see far to the south, including another large impact crater that lies 10 km or so south of Endeavour.”

The rover has survived its seventh winter on Mars—over 12 years (a Martian year being a bit longer than an Earth year)—an amazing accomplishment for a machine which was built to nominally last 90 days in the frigid, dry Martian environment.

“Opportunity has stayed very active this winter, in part because the solar arrays have been much cleaner than in the past few winters,” said Callas.

“Twelve years is a very long time to have this sort of a continuous presence,” added Matt Golombek, Mars rovers project scientist. “For a science team to be this involved, on a daily basis, for this long on Mars, is pretty much unprecedented.”

Opportunity landed on Jan. 24, 2004, PST (early Jan. 25, UTC), to begin its mission in Meridiani Planum. It was designed to search for clues relating to the potential habitability of Mars in the ancient past, including water. It has done that, and much more, in the 12 years since. Despite that, there was a nail-biting waiting period, when it wasn’t known if the mission would be funded again through 2016. There had been concern that the new budget would mean having to shut down the rover prematurely, even though it was still healthy and active. But it was funded and, according to Emily Lakdawalla of The Planetary Society, it should remain funded now as long as it is still functioning and able to return science data:

“Generally speaking, if you have a spacecraft that is functional, that is responding to you, that is already at a distant planet, it is worth it to continue to put what effort you can in to get science out of it.”

That is good news indeed for such a robust and long-lasting mission. Nobody knows how much longer Opportunity will survive, but right now it is still accomplishing amazing science and has helped revolutionize our understanding of Mars’ ancient past.

More information about the Opportunity rover mission is available here.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Lakdawalla hits the nail on the head! It would be a travesty NOT to continue funding so long as Opportunity continues its stellar work. To use my favorite expression, “It’s chump change” for such a wealth of scientific return.

Tom Vasiloff

Yep, I agree.

Similarly, I also agree with your ISS comment on January 8, 2014 at 5:51 pm:

“This extension of ISS to at least 2024 or 2028 may prove to be a significant development in conjunction with BEO capabilities. Imagine the ISS as a “stopover” point on the way to the Moon or Mars. There may well be new capabilities of the ISS not currently planned but potentially adaptable to new missions.”

We need to extend the missions of our valuable and famous space and planetary exploration systems that are efficiently and productively already working for us.

I hope to eventually see a sixth human or robotic enabled servicing mission for the versatile and unique Hubble Space Telescope.

Not only is Opportunity able to return valuable scientific data about Mars but also about itself. Data from a craft that was expected to stop functioning so long ago is invaluable to future Mars missions. Data pertaining to parts that have failed, as well as those that have not, will allow engineers of future missions to ask: why did those parts fail? Why DIDN’T other parts fail? Thus, they will be able to build more resilient craft for the future.