As reported a few days ago, the Juno spacecraft orbiting Jupiter had entered safe mode, a precautionary turning off of all but vital instruments and other components when a software performance monitor induced a reboot of the spacecraft’s onboard computer. Now, Juno has successfully exited safe mode and is otherwise healthy and ready to continue its exploration of Jupiter.

“Juno exited safe mode as expected, is healthy and is responding to all our commands,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “We anticipate we will be turning on the instruments in early November to get ready for our December flyby.”

The Juno mission team is preparing for the next close orbital flyby of Jupiter on Dec. 11, and the spacecraft completed a small burn of its thruster engines yesterday. The orbital trim maneuver was conducted on Tuesday at 11:51 a.m. PDT (2:51 p.m. EDT) using the spacecraft’s smaller thrusters. The burn lasted just over 31 minutes and changed Juno’s orbital velocity by about 5.8 mph (2.6 meters per second), consuming about 8 pounds (3.6 kilograms) of propellant in the process.

Barring any more safe modes, all of Juno’s instruments will be used during this flyby, with closest approach scheduled for 9:03 a.m. PDT (12:03 p.m. EDT).

“We are all excited and eagerly anticipating this next pass close to Jupiter,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “The science collected so far has been truly amazing.”

Juno had first entered safe mode on Tuesday, Oct. 18, at about 10:47 p.m. PDT (Oct. 19 at 1:47 a.m. EDT). The spacecraft conducted a close flyby of Jupiter on Wednesday, Oct. 19, but because it was in safe mode at the time, no science data was collected.

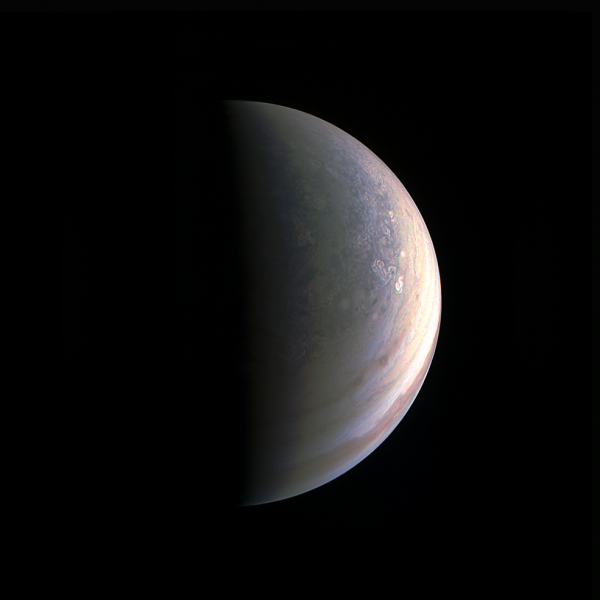

Juno will fly closer to Jupiter’s cloud tops than any previous spacecraft, as close as 2,600 miles (4,100 kilometers)—the first time a spacecraft has orbited so close to Jupiter, beneath the deadly radiation belts. This vantage point has already provided some extraordinary new views of Jupiter’s beautiful and chaotic atmosphere, in particular the north and south poles, which until now had not been seen in as much detail as the rest of the planet. While most of Jupiter’s clouds form the well-known distinct bands around the equator and mid-latitudes, the poles are dominated by smaller hurricane-like circular eddies. They are, however, still much larger than any hurricanes on Earth. There is also no “hexagon” shaped pattern at the pole, as is seen on Saturn.

The north pole, in fact, is unlike that of any other planet seen so far.

“First glimpse of Jupiter’s north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before,” said Bolton. “It’s bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms. There is no sign of the latitudinal bands or zone and belts that we are used to – this image is hardly recognizable as Jupiter. We’re seeing signs that the clouds have shadows, possibly indicating that the clouds are at a higher altitude than other features.”

“Saturn has a hexagon at the north pole,” added Bolton. “There is nothing on Jupiter that anywhere near resembles that. The largest planet in our solar system is truly unique. We have 36 more flybys to study just how unique it really is.”

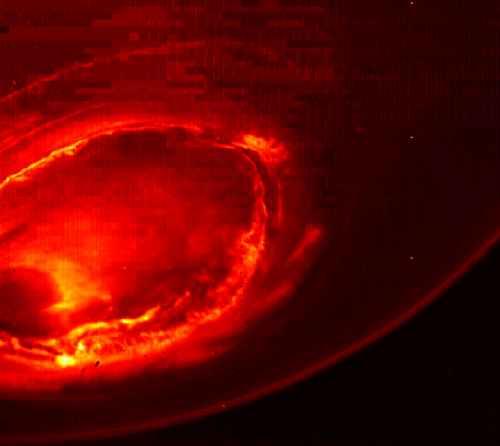

During Juno’s first close flyby last August, all eight of the science instruments were collecting data, and it will be the same for the next flyby in December. The Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) also took infrared images of the polar regions.

“JIRAM is getting under Jupiter’s skin, giving us our first infrared close-ups of the planet,” said Alberto Adriani, JIRAM co-investigator from Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome. “These first infrared views of Jupiter’s north and south poles are revealing warm and hot spots that have never been seen before. And while we knew that the first-ever infrared views of Jupiter’s south pole could reveal the planet’s southern aurora, we were amazed to see it for the first time. No other instruments, both from Earth or space, have been able to see the southern aurora. Now, with JIRAM, we see that it appears to be very bright and well-structured. The high level of detail in the images will tell us more about the aurora’s morphology and dynamics.”

Juno has even recorded radio transmissions coming from Jupiter, acquired by the Radio/Plasma Wave Experiment (Waves).

According to Bill Kurth, co-investigator for the instrument from the University of Iowa in Iowa City: “Jupiter is talking to us in a way only gas-giant worlds can. Waves detected the signature emissions of the energetic particles that generate the massive auroras which encircle Jupiter’s north pole. These emissions are the strongest in the Solar System. Now we are going to try to figure out where the electrons come from that are generating them.”

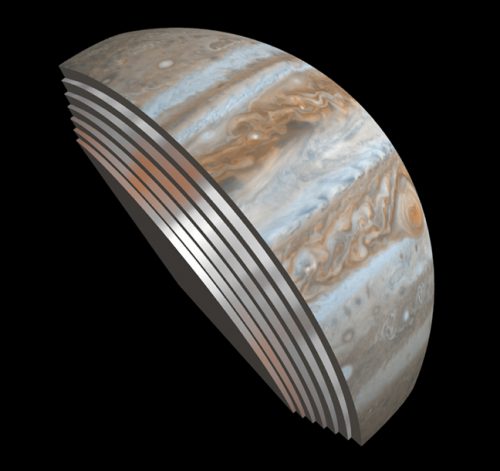

Before entering safe mode, Juno peered deep into Jupiter’s atmosphere, revealing how the cloud bands can be seen even in layers farther down from the cloud tops. Using its Microwave Radiometer (MWR) instrument and its largest antenna, MWR can “see” about 215 to 250 miles (350 to 400 kilometers) below the top cloud deck.

“With the MWR data, it is as if we took an onion and began to peel the layers off to see the structure and processes going on below,” said Bolton. “We are seeing that those beautiful belts and bands of orange and white we see at Jupiter’s cloud tops extend in some version as far down as our instruments can see, but seem to change with each layer.”

Beautiful and highly energetic aurora, much larger than any on Earth, have also been seen at Jupiter’s poles, and now viewed in new detail by Juno.

“These first infrared views of Jupiter’s north and south poles are revealing warm and hot spots that have never been seen before. And while we knew that the first-ever infrared views of Jupiter’s south pole could reveal the planet’s southern aurora, we were amazed to see it for the first time. No other instruments, both from Earth or space, have been able to see the southern aurora. Now, with JIRAM, we see that it appears to be very bright and well-structured. The high level of detail in the images will tell us more about the aurora’s morphology and dynamics,” said Adriani.

Even though Juno has only been orbiting Jupiter for a few months, it has already returned a rich scientific harvest from the largest planet in the Solar System.

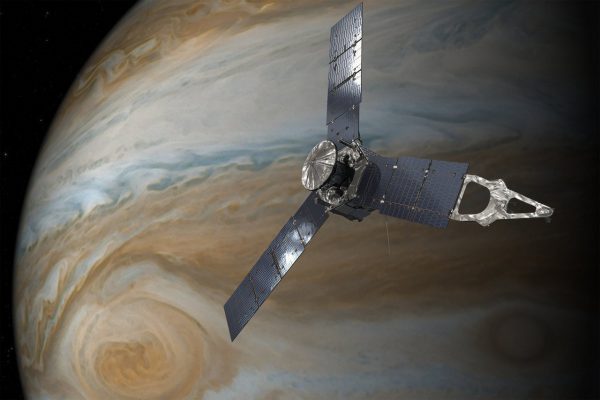

Juno first arrived at Jupiter on July 4, 2016, and will conduct a planned series of 37 close flybys of the planet. The main objectives of the mission include investigating the existence of a possible ice-rock core, determining the amount of global water and ammonia present in the atmosphere, studying convection and deep wind profiles in the atmosphere, investigating the origin of the Jovian magnetic field, and exploring the polar magnetosphere. It is the first solar-powered spacecraft to fly to the outer Solar System, first breaking the distance record on Jan. 13, 2016, and the first spacecraft ever to fly with 3-D printed titanium parts.

More information about the Juno mission is available on the NASA website.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Juno spacecraft exits safe mode, prepares for next close flyby of Jupiter in December