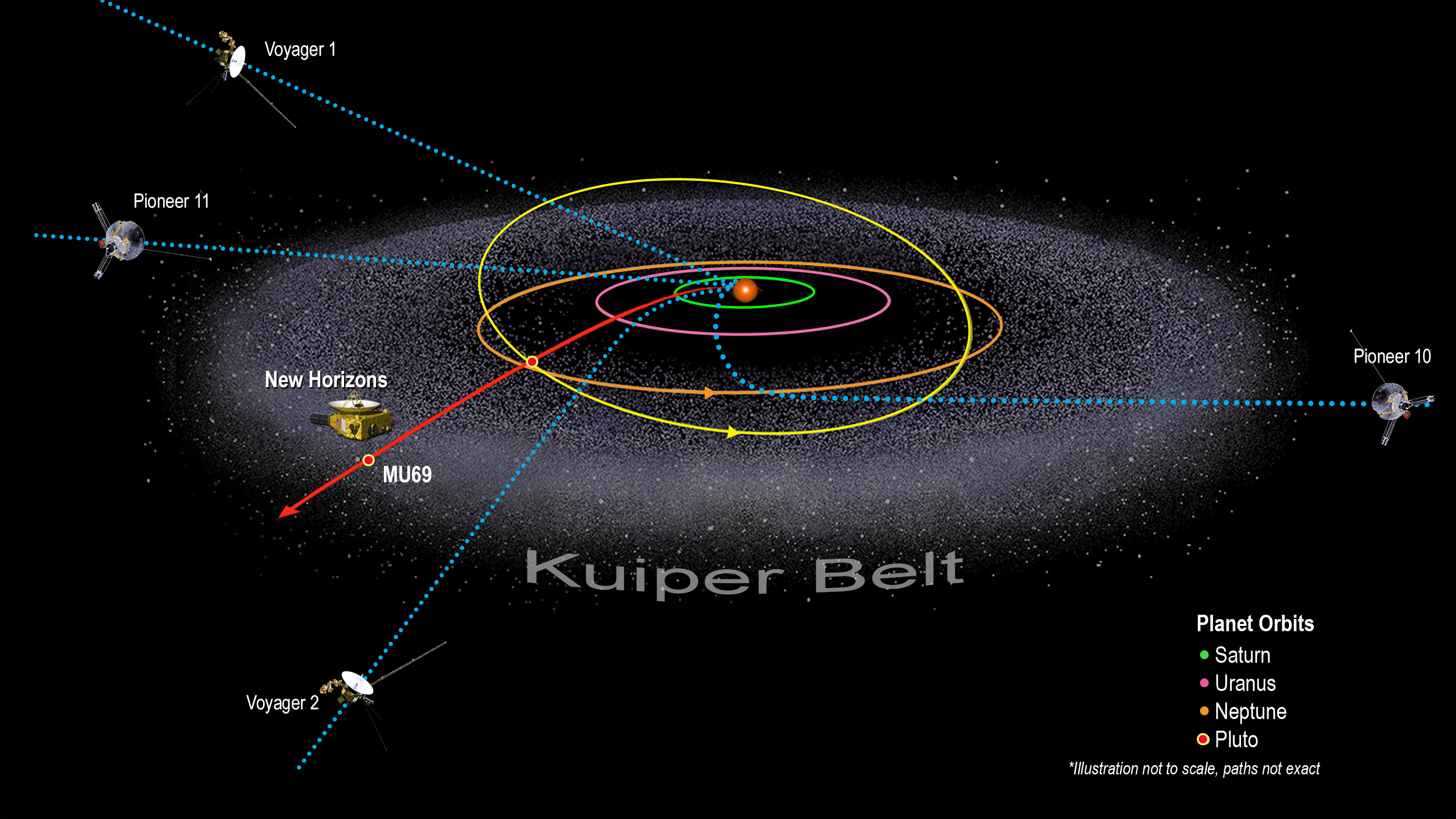

The Kuiper Belt is a vast region of rocky debris in the outer Solar System beyond Neptune, similar to the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The objects in this belt – Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) – are ancient, left over from the formation of the Solar System billions of years ago, and range in size from a few hundred feet to a few thousand miles.

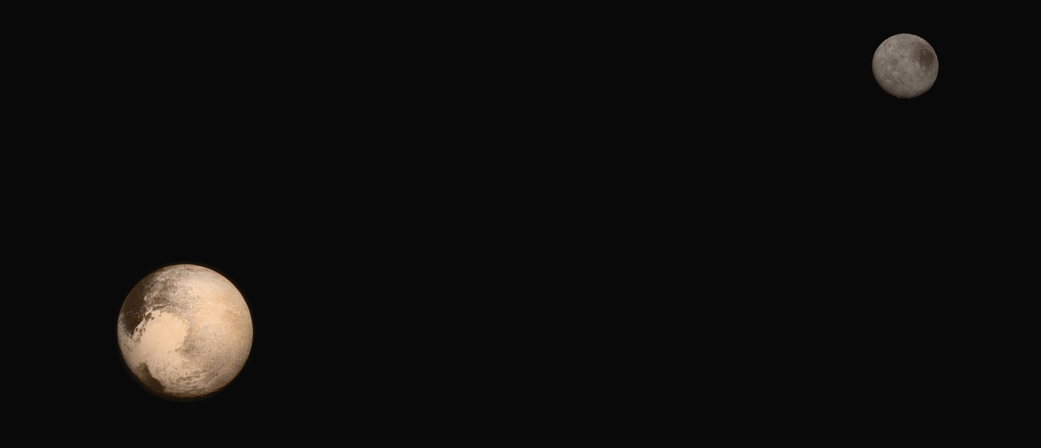

Pluto is the largest of these worlds, and while there is a great range in sizes of KBOs, a new study has shown that there is a surprising lack of the smallest objects less than a mile in size.

The new research, led by scientists from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), was published in the March 1 issue of the journal Science.

“Collisions between Solar System bodies produce impact craters on large objects at a rate that depends on the population of impacting small bodies. Singer et al. examined impact craters on Pluto and its moon Charon. Some regions have had their impact craters erased by recent geological processes, but others appear to record 4 billion years of impacts. Because Pluto and Charon are located in the Kuiper belt, the distribution of crater sizes reflects the size distribution of impacting Kuiper belt objects (KBOs). The authors found fewer small KBOs than predicted by models of collision equilibrium, implying that some of the KBO population has been preserved since the formation of the Solar System.”

“These smaller Kuiper Belt objects are much too small to really see with any telescopes at such a great distance,” said SwRI’s Dr. Kelsi Singer, the paper’s lead author and a co-investigator of NASA’s New Horizons mission. “New Horizons flying directly through the Kuiper Belt and collecting data there was key to learning about both large and small bodies of the Belt.”

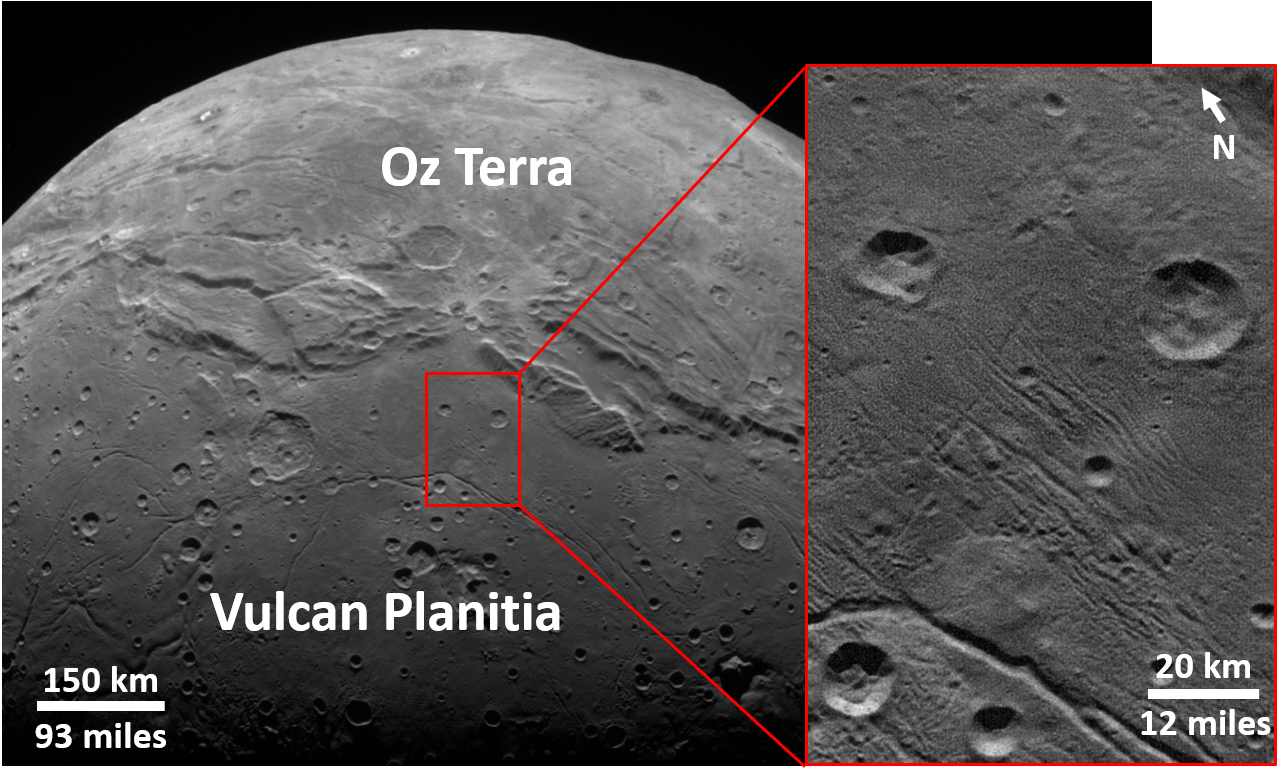

So how did the researchers determine this? The answer comes from the New Horizons flyby of Pluto and its moons in 2015. The research team studied images of Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, and found that there was a dearth of small craters, less than expected. This means that small impactors – asteroids or comets from 300 feet to 1 mile (91 meters to 1.6 kilometers) in diameter – must be rare in the Kuiper Belt.

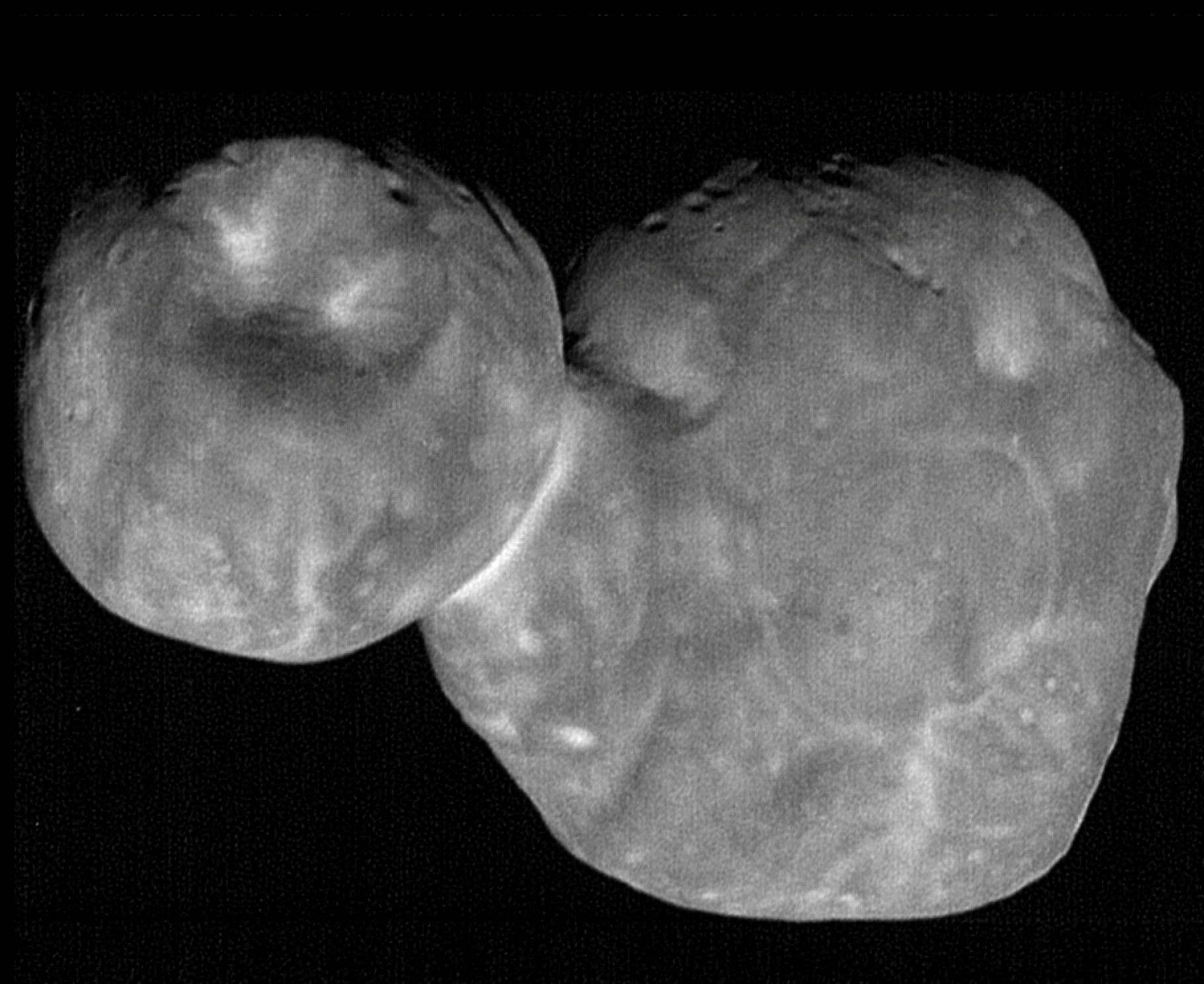

“This breakthrough discovery by New Horizons has deep implications,” added the mission’s principal investigator, Dr. Alan Stern, also of SwRI. “Just as New Horizons revealed Pluto, its moons, and more recently, the KBO nicknamed Ultima Thule in exquisite detail, Dr. Singer’s team revealed key details about the population of KBOs at scales we cannot come close to directly seeing from Earth.”

If smaller impactors were more common, then there should be more smaller craters on bodies like Charon. Charon is a better case study than Pluto because more of Pluto’s craters have been erased by geologic processes; most of Charon’s craters, however, are still visible.

“A major part of the mission of New Horizons is to better understand the Kuiper Belt,” said Singer. “With the successful flyby of Ultima Thule early this year, we now have three distinct planetary surfaces to study. This paper uses the data from the Pluto-Charon flyby, which indicate fewer small impact craters than expected. And preliminary results from Ultima Thule support this finding.”

“This surprising lack of small KBOs changes our view of the Kuiper Belt and shows that either its formation or evolution, or both, were somewhat different than those of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter,” said Singer. “Perhaps the asteroid belt has more small bodies than the Kuiper Belt because its population experiences more collisions that break up larger objects into smaller ones.”

As noted above by Singer, this conclusion is also supported by the findings from the Ultima Thule (2014 MU69) flyby on Jan. 1, 2019, when New Horizons sped past the most distant object in the Solar System to ever be visited by a spacecraft from Earth. It also showed few craters, and some pits seen may turn out to not even be craters at all (to yet be determined).

That flyby provided the first close-up views of this tiny world, much smaller than Pluto or Charon, showing it as a binary, double-lobed object, where the one lobe is round and surprisingly flat – almost like a pancake, and the other lobe looks like a dented walnut. The highest-resolution images of this bizarre object were released on Feb. 22, 2019.

The objects in the Kuiper Belt, even the largest ones, are very difficult to see from Earth, but thanks to New Horizons, we now have much more information about their sizes, origin and evolution in the early Solar System.

More information about New Horizons is available on the mission website.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Missions » New Horizons »