A little more than a week since his passing, aged 82, veteran astronaut and Navy Capt. Eugene Cernan—the last man to have left his footprints on the surface of the Moon—was honored today in a touching funeral service at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church in Houston, Texas. Veteran astronaut and Navy Capt. Jim Lovell, together with Cernan’s naval aviator buddy and close friend of six decades, Cmdr. Fred “Baldy” Baldwin delivered eulogies to their fallen comrade. It is expected that Cernan will be laid to rest in a private interment at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin at a later date, where full military honors will be rendered to one of the youngest men ever to attain the rank of Captain in the U.S. Navy.

Today’s funeral service was delivered by the Rector of St. Martin’s, the Rev. Dr. Russell J. Levenson, Jr., who admitted that his friendship with Cernan had only come about in the closing years of the astronaut’s life. He remembered his own sense of awe and wonder at having grown up during the glory days of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, watching our species’ first steps on the surface of another world. It was, said the Rector, a totally different world: a world of boxy televisions, with just two channels (or three, dependent upon whether one possessed a UHF antenna) to witness those remarkable steps.

With six of the 12 Apollo Moonwalkers now having left us, the sense of grief at Cernan’s passing remains palpable; not least due to the reality that we are no closer to returning to our closest celestial neighbor than we were when the Apollo 17 Command Module (CM), dubbed “America,” splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, in December 1972. The world lost Jim Irwin in August 1991, Al Shepard in July 1998, Charles “Pete” Conrad in July 1999, Neil Armstrong in August 2012, and, most recently, Ed Mitchell in February 2015. With Cernan now gone, only a half-dozen humans remain alive to share the experience of having set foot on the surface of a world beyond our own.

That, indeed, is a sobering thought.

In recent days, thousands of tributes have been paid to Cernan, most visibly from astronauts whose own journeys to low-Earth orbit are a far cry from the 240,000-mile (370,000 km) voyage across cislunar space to the Moon. Veteran shuttle spacewalker Mike Foreman tweeted last week that “the passing of Gene Cernan reminds us how far we haven’t come.” Others, including former International Space Station (ISS) resident Ron Garan, added a wish that “we honor his legacy, by returning to the Moon as we came, ‘with peace and hope for all mankind.’” The commanders of the final missions of Space Shuttles Endeavour and Atlantis—Mark Kelly and Chris Ferguson—also extended their own thoughts: the former describing him as “a good friend” and “brave explorer,” and the latter paying tribute to a “fellow veteran Navy carrier pilot” and “a spaceflight icon.”

Key speakers today included veteran Gemini and Apollo astronaut Jim Lovell, who served on the backup crew for Cernan’s Gemini IX-A mission in June 1966. Interestingly, the pair later switched crews and Cernan served on the backup crew for Lovell’s Gemini XII mission in November 1966. Also offering his memories was Fred “Baldy” Baldwin, an old squadron buddy of Cernan. In the recent documentary The Last Man on the Moon, Cernan and Baldwin’s good-natured cat-and-dog quarrels—forever trying to one-up the other—produced a somewhat comical exchange:

“Why were you such a bad bomber pilot, Gene?”

“Baldy,” replied Cernan, pointing at the Moon. “That’s 240,000 miles away.”

“Aww,” drawled Baldwin, “anybody can hit that!”

In his remarks, Dr. Levenson described Cernan as a living, breathing embodiment of Newton’s First Law—that an object in motion stays in motion, with the same speed and in the same direction, unless acted upon—in that nothing ever seemed to slow him down, even in old age. “Gene lived an abundant life,” said the Rector. “He fired through life at full throttle.” Yet in spite of his naval aviator’s swagger and ego and achievements, he lacked arrogance and, rather, was humbled by his experiences. Moreover, in recent years, he dedicated himself to encouraging the activities of the young to make their dreams come true. He turned the question “Why me?” on its head, reversing it as “Why not you?” And, indeed, those “yous” may someday find themselves standing on the surface of the Moon, as he did, all those years ago.

The Rector paid tribute to Cernan’s daughter, Teresa—nicknamed Tracy—who achieved a degree of fame, when her father inscribed her initials (T.D.C.) into the lunar soil at Taurus-Littrow. In all likelihood, they will remain for thousands of years. A son, said Dr. Levenson, is a son until he gains a wife, but a daughter is a daughter for life. And one of the last things Cernan told Dr. Levenson was that Tracy was so beautiful that he could look at her forever. “She knows Gene is looking down at her,” he said, “and she will always look up at him.”

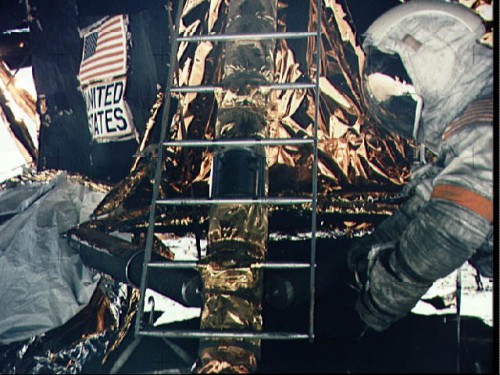

There are, the Rector added, the finger-etched initials T.D.C. on the surface of the Moon, but Cernan’s own mark remains with us. Once, Dr. Levenson asked the astronaut if he was ever fearful of the Lunar Module (LM), dubbed “Challenger,” being unable to launch from the lunar surface. Cernan’s response: “I just didn’t think about it.” The fear was overwhelmed by the view of looking back from the Moon, toward the blue marble of Earth, and the sensation that he was sitting on God’s front porch, seeing the planet as God saw it, with races breathing the same air of a common home.

“His time on the Moon’s surface was short; he didn’t get to stay as long as he wanted,” Dr. Levenson told his congregation. “Time with Gene here has passed and it seems to have come too soon. In our world, full of distractions, we tend to rush through life and at times like this, we have a temptation to rush beyond grief.”

And then the Rector paused for a moment, then spoke.

“Today, I bid you: do not let the sun go down, without that honest confession: I miss him!”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Well done, Gene. And thank you.