Forty-five years ago, today, a fully-suited astronaut poked his helmeted head out of the side hatch of the Command and Service Module (CSM) into an environment like no other. Ron Evans, one of the three astronauts of Apollo 17—our most recent piloted voyage to the Moon—was tasked with retrieving film from cameras in the Scientific Instrument Bay (SIMbay) aboard the service module. To do that, he had to clamber, hand over hand, across a distance of 30 feet (9 meters), and back again. “Spacewalks” had been performed several times by Evans’ day, but most had been done in low-Earth orbit, with the Home Planet in relatively close proximity. Evans remains one of only three men to have made a “deep space walk”, in the cislunar void between Earth and our nearest celestial neighbor.

Video Credit: NASA

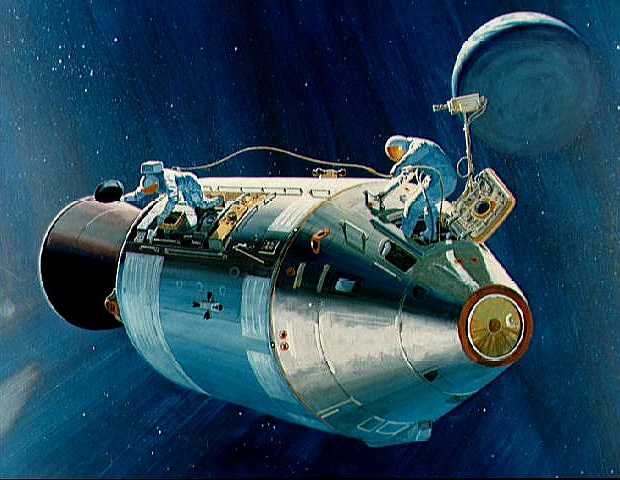

The final three manned missions to lunar distance, Apollos 15 through 17, flown between July 1971 and December 1972, were also the most complex. Known as “J-series” missions, they were characterized by an upgraded Lunar Module (LM), capable of three-day stays on the surface, and a CSM brimming with SIMbay instrumentation to comprehensively survey the Moon. Whilst the Commanders and Lunar Module Pilots (LMPs) of the three missions descended to the rugged mountainous terrain of Hadley-Apennine, Descartes and Taurus-Littrows, the Command Module Pilots (CMPs) remained in orbit, overseeing a significant program of observations and measurements.

Since the cylindrical service module could not survive re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, it was imperative that the CMPs ventured outside to retrieve their camera film during the return journey. On Apollo 15, Al Worden performed the feat, followed by Ken Mattingly on Apollo 16 and, lastly, Evans on Apollo 17. The deep-space walks, or “Trans-Earth” Extravehicular Activities (EVAs), would occur further from Earth than ever before. In fact, the Moon—just 60,000 miles (100,000 km) distant—loomed large in the astronauts’ view, whilst the Home Planet resembled a blue-and-white football, 180,000 miles (300,000 km) away.

Spacewalks were not originally the intended means of getting SIMbay film back aboard the command module. In May 2000 oral history for NASA, Al Worden noted that other methods were discussed, including a clothesline-like reel, but a spacewalk proved the most practical option. “There had already been some preliminary work on how to get this film out of the SIMbay,” Worden told the NASA oral historian. “Of course, it had been in the pipeline for several years and there were a lot of schemes to get the film from…the back of the Scientific Instrument Module all the way up into the command module, a distance of about 30 feet. How do you get out there safely so that you don’t lose it, so that you don’t hurt something? One of the schemes was…an “arm” on a hinge that would go out and pick up the film and…bring it back by the hatch, where you could pick it up.”

When Worden performed the first trans-Earth EVA on 5 August 1971, he had rehearsed every step over 300 times. “The EVA itself was kind of unique,” Worden said of the relatively brief, 39-minute excursion, “sort of a unique perspective. I did have a chance to stand up on the outside [of the service module] and look. I could see the Moon and the Earth at the same time; and if you’re on Earth, you can’t do that, and if you’re on the Moon, you can’t do that! It’s a very unique place to be. I guess our biggest concern was that we had everything tied down so that when we opened the hatch, we didn’t have something go wandering off into space! But outside of that, it was pretty easy.”

Since the spacecraft’s cabin was reduced to vacuum for the trans-Earth EVAs, it was necessary for the other members of the crew to also be fully suited. On Apollo 15, Jim Irwin remembered that opening the hatch created an effect not dissimilar to a vacuum cleaner, as all unsecured objects began drifting around, including toothbrushes and cameras. Unlike terrestrial spacewalks, the astronauts were surrounded by the pitchest blackness and one of the few sources of illumination was sunlight, reflected by the shiny surface of the service module.

Eight months later, on 25 April 1972, astronaut Ken Mattingly became the second human to perform a deep-space EVA, as Apollo 16 returned from the Moon. Wearing Commander John Young’s helmet, equipped with a gold-tinted sun visor, he spent more than an hour outside, collecting not only the SIMbay film, but also setting up and later retrieving a set of microbial samples in the command module’s hatch. He also lost—and then found—his wedding ring, which had somehow gotten lost in the recesses of the spacecraft, before floating outside. It was his crewmate Charlie Duke who spotted the ring and Mattingly grabbed it and quickly jammed it into his pocket. “We had the chances of a gazillion-to-one,” Mattingly later recalled. It must have been a relief for his wife, Elizabeth.

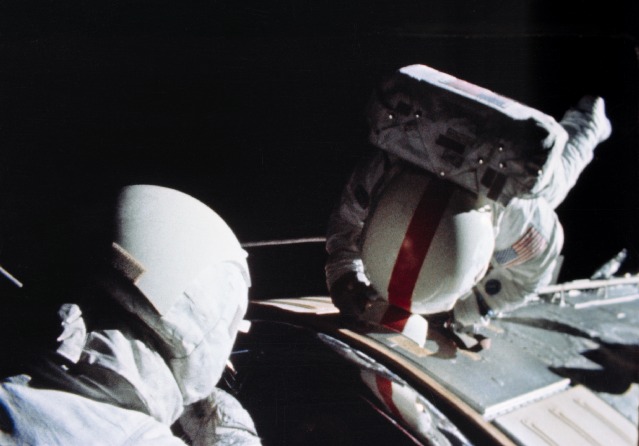

With Worden’s 39-minute excursion and Mattingly’s 84 minutes spent outside, it would be Ron Evans on Apollo 17 on 17 December 1972 who would complete the most recent trans-Earth EVA. Early that morning, 45 years ago today, the crew removed the center couch in the command module, to give Evans the room he needed to get outside. LMP Jack Schmitt would be positioned in the hatchway to assist him, whilst Commander Gene Cernan would handle the spacecraft systems.

For 2.5 hours, the three men labored in the limited elbow-room reserves of the command module to get themselves ready for the spacewalk. Cernan, whose own EVA on Gemini IX-A in June 1966 had encountered severe difficulties—partly due to the lack of hand-holds—advised Evans to take his time. “When you get out there, just take it nice and slow and easy,” he said. “You got all day long.” Cernan cautioned not to move too quickly and to feel his way along the exterior of the spacecraft. As the side hatch opened, Schmitt offered his own words of encouragement. “Nice day for an EVA, Ron. Go out and have a good time!”

Like Mattingly on Apollo 16, Evans was also wearing his commander’s helmet, equipped with red stripe and gold-tinted Lunar Extravehicular Visor Assembly (LEVA). Although he had griped that the gold visor made it hard for him to see anything inside the cabin, Cernan and Schmitt assured him that he would need its protection during the spacewalk.

As the hatch opened, a felt-tipped pen drifted outside. Next came Evans himself. Emerging into the void, he was presented with the electrifying view of a crescent Earth, straight ahead, before being arrested by the blinding glare of the Sun to his right. Cernan advised him to pull down his gold-tinted visor, which Evans promptly did. Having identified himself to Mission Control as “the CMP” for most of the mission, he seemed a little unsure of how to identify himself. “Houston, this is…let’s see…when you’re EVA, they use your name, don’t they?”

“Yessir, we’ll use it, Ron,” replied Capcom Bob Overmyer.

Evans’ first act was to install a pole for the television camera, after which he conducted a visual survey of the service module’s external skin. Some of the paint was blistered, he noted, which readily peeled off with the fingers. Humming to himself, Evans moved to the SIMbay and set himself up in the foot restraints. “Talk about being a spaceman,” he breathed. “This is it!” It was also surprising to witness Earth as a crescent, having seen the Moon in such a phase so many times during his life. “The crescent Earth is not like the crescent Moon,” Evans reflected. “It’s got kind of like…horns…and the horns go all the way around, and it makes almost three-quarters of a circle.”

In spite of the lightheardtedness, there was much work to do. He hooked a tether onto the SIMbay’s lunar sounder data-cassette, thereby ensuring that it would not float away. After returning the cassette to a waiting Schmitt in the command module’s hatchway, Evans returned to the rear of the service module to pick up the pan camera’s data-cassette. At one stage, he paused for a breather and offered a brief “Hi” greeting to his mother, wife and children. All told, Evans was outside for 67 minutes, becoming the 21st human being in history to perform an extravehicular activity and only the third to do so in the vast cislunar gulf between Earth and the Moon.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook!

.

My understanding is that no photos were taken of Worden, Mattingly and Evans with the moon as a bak drop. If true, the world missed out on a spectacular series of images that would have been quite a compliment to the lunar surface photos.