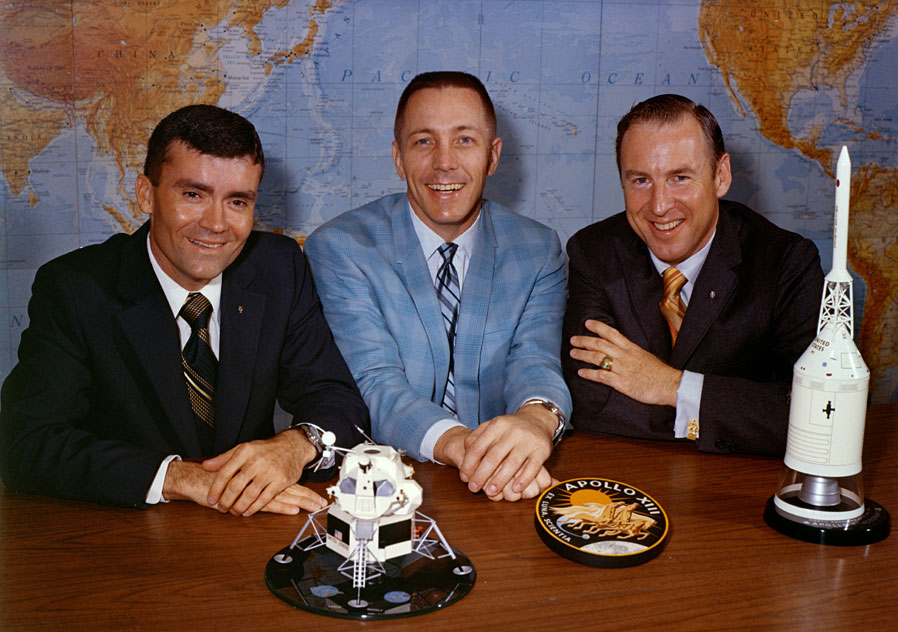

In an alternate universe, Jim Lovell and Fred Haise should have been the fifth and sixth sons of humanity to have walked the surface of an alien world. In April 1970, the pair—joined by their Apollo 13 crewmate Jack Swigert—launched on the fifth piloted mission to the Moon, with an expectation that Lovell and Haise would land in a hilly region called Fra Mauro. As outlined in last week’s AmericaSpace history article, the site lay to the south of the 750-mile-wide (1,200 km) Imbrium basin, an ancient impact feature, and it was hoped that Apollo 13’s explorations would yield new clues into the composition of the early lunar crust. After touching down on the Moon, aboard their Lunar Module (LM) Aquarius, Lovell and Haise would spend 33.5 hours on the surface and perform two sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA), each baselined at four to five hours in duration.

Plans for a “rest” period in the immediate aftermath of landing had long since been abandoned, and it was anticipated that Lovell and Haise would be suited up and ready to begin the first of their two EVAs at 2:13 a.m. EDT on 16 April 1970. The duo would set up an erectable S-band antenna, about 50 feet (15 meters) from Aquarius, for relaying voice, television, and LM telemetry data to Earth-based stations. “After the antenna is deployed, Haise will climb back into the LM to switch from the LM steerable S-band antenna to the erectable antenna, while Lovell makes final adjustments to the antenna’s alignment,” it was noted by NASA. “Haise will then rejoin Lovell on the lunar surface to set up a United States flag and continue with EVA tasks.”

Core objectives would have encompassed the collection of a “contingency” sample of about 2 pounds (900 grams) of lunar soil, the unveiling of a commemorative plaque on Aquarius’ leg and the deployment of the second Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP). The latter, situated about 500 feet (150 meters) from the LM, would have supported five discrete investigations: the instrumented probes of the Heat Flow Experiment (HFE), the Dust Detector, the Charged Particle Lunar Environment Experiment (CPLEE), the Cold Cathode Gauge Ion Instrument of the Lunar Atmosphere Detector (LAD), and the Passive Seismic Experiment (PSE). “These experiments are aimed toward determining the structure and state of the lunar interior, the composition and structure of the lunar surface and processes which modify the lunar surface, and evolutionary sequence leading to the Moon’s present characteristics,” NASA explained. “The Passive Seismic Experiment will become the second point in a lunar seismic “net”, begun with the first ALSEP at the Surveyor III landing site of Apollo 12. The two seismometers must continue to operate until the next seismometer is emplaced to complete the three-station set.”

In particular, the HFE would have required Haise to drill a pair of 10-foot-deep (3.3-meter) holes with the Apollo Lunar Surface Drill (ALSD). Meanwhile, Lovell would have busied himself with the assembly of the ALSEP Central Station. The pair would then have headed about a half-mile (800 meters) to the west to begin their first period of scientific exploration, venturing as far as the rim of Star Crater. They would have returned to the LM in a looping elllipse, by way of the Doublet crater group, and Haise would have deployed the Solar Wind Composition Experiment (SWCE). This would have concluded a maximum EVA-1 traverse of 5,000 feet (1,150 meters).

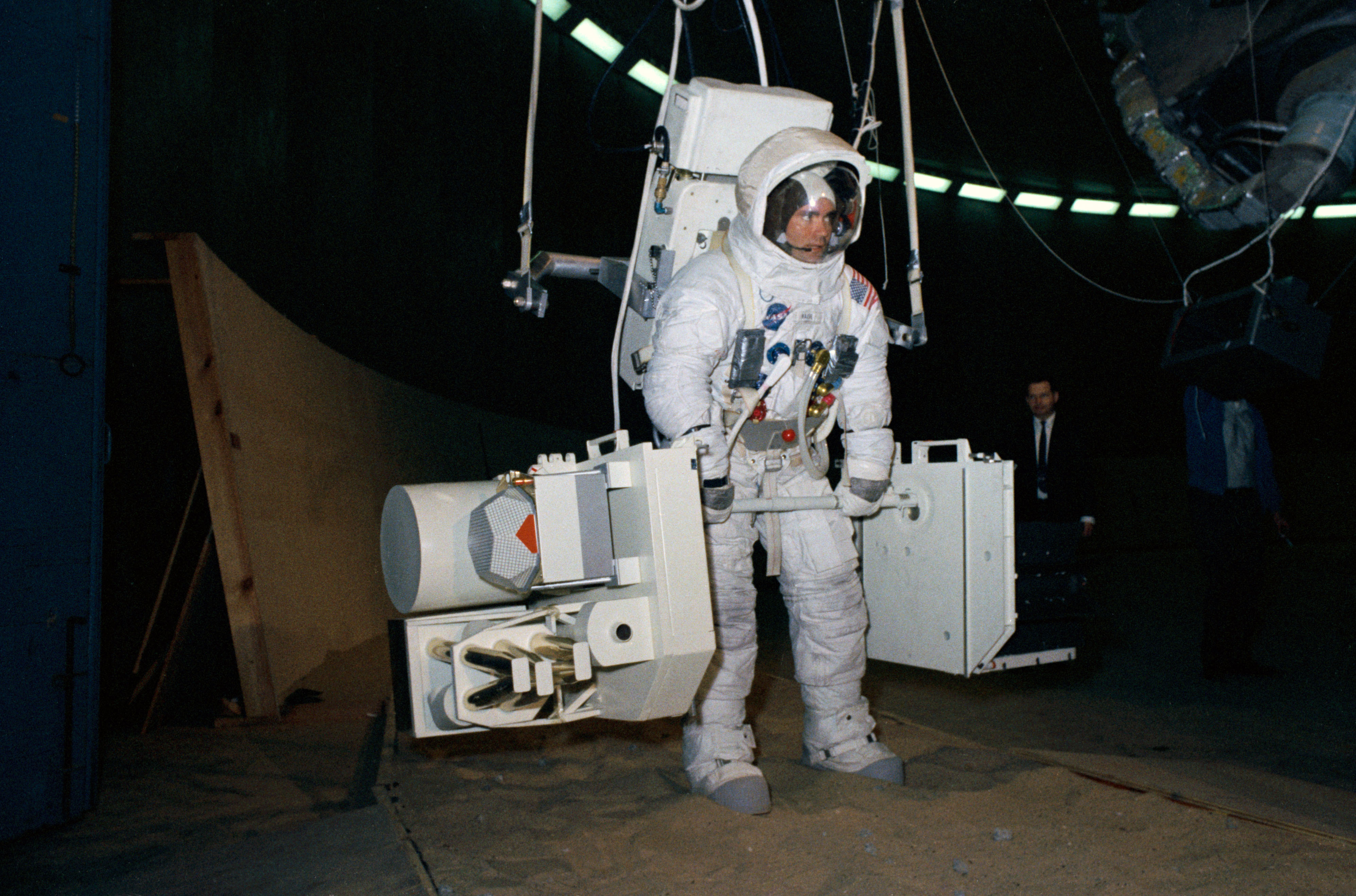

Lovell and Haise’s time outside would be tightly constrained, and the clock would forever work against them. “While on the surface, the crew’s operating radius will be limited by the range provided by the Oxygen Purge System (OPS), the reserve backup for each man’s Portable Life Support System (PLSS) backpack,” it was highlighted. “The OPS supplies 45 minutes of emergency breathing oxygen and suit pressure.” Unlike the crews of the two previous Apollo landing missions, Lovell and Haise’s snow-white suits would have been easily distinguishable, for the Commander’s ensemble was emblazoned for the first time with red stripes around its elbows and knees for identification. “Another modification since Apollo 12 has been the addition of 8-ounce (225-gram) drinking water bags, attached to the inside neck rings of the EVA suits,” NASA noted. “The crewmen can take a sip of water from the 6 x 8-inch (15 x 20 cm) bag through a 1/8-inch (0.3 cm) tube within reach of his mouth.”

Returning to Aquarius, the astronauts would have grabbed a bite to eat in the broom-closet-sized LM and struggled to catch some sleep. Their second EVA was scheduled to begin at 9:58 p.m. EDT on 16 April 1970, and it would feature the first “real” scientific inspection of the Fra Mauro site. Their EVA-2 traverse was expected to cover 8,700 feet (2,650 meters), of which 4,500 feet (1,370 meters) was the outbound half and 4,200 feet (1,280 meters) was the inbound portion, back toward Aquarius. Two sampling stops on the hilly approach to Cone Crater would have allowed Lovell and Haise to gather rock and soil specimens, potentially from lava flow or Imbrium impact material, and they would have moved slowly uphill to reach the rim of the crater, some 400-600 feet (120-180 meters) above the neighboring terrain.

“Almost the entire second EVA will be devoted to Field Geology Investigations and the collection of documental samples,” it was noted in the Apollo 13 Press Kit. “The sample locations will be carefully photographed before and after sampling. The astronauts will carefully describe the setting from which the sample is collected. In addition to specific tasks, the astronauts will be free to photograph and sample phenomena which they judge to be unusual, significant and interesting. The astronauts are provided with a package of detailed photo maps, which they will use for planning traverses. Photographs will be taken from the LM window. Each feature or family of features will be described, relating to features on the photo maps. Areas and features where photographs should be taken and representative samples collected will be marked on the maps. The crew and their ground support personnel will consider real-time deviation from the nominal plan, based upon an on-the-spot analysis of the actual situation.” Both Lovell and Haise would have carried a Lunar Surface Camera, which comprised a modified 70 mm electric Hasselblad.

The two men would put their geological training to good use in collecting several core tube samples, digging a 2-feet-deep (60 cm) trench to evaluate soil mechanics and gas dynamics and collecting a variety of rock samples. During the return journey to the LM, they would have paused at Flank Crater, dug a trench, gathered samples, and bored a 27-inch (68.5 cm) double core tube into the regolith at Weird Crater, before closing out EVA-2 with a soil mechanics sample. Their samples—of which about 95 pounds (43 kg) were planned to be loaded aboard Aquarius’ ascent stage for the return to lunar orbit—would include “core samples, individual rock samples and fine-grained fragments.” Moreover, Lovell and Haise were expected to use a Lunar Stereo Close-up Camera to image “small geological features that would be destroyed in any attempt to gather them for return to Earth.”

In his NASA Oral History, Haise reflected that he and Lovell and their backups—John Young and Charlie Duke—were the first Apollo crew to be extensively schooled by Dr. Lee Silver of California Institute of Technology, together with scientist-astronaut Jack Schmitt. In the months before launch, the prime and backup crews, Silver and Schmitt journeyed into the Orocopia Mountains of southern California, to develop their skills as lunar field geologists. “We would go through two or three exercises a day, using Polaroids in that timeframe, to record the events, and get debriefs from Lee, and discuss geology around a campfire till like 10 or 11 at night,” Haise remembered. “It was a real fast dose and startup of what was kind of the ritual that followed with many of the ensuing field trips, although it got refined in a higher way with equipment we used and more involvement with the back room people who were going to be there during the mission.”

Their lunar explorations concluded, Lovell and Haise would have lifted off from the Moon at 7:22 a.m. EDT on 17 April 1970, after 33.5 hours on the surface, and docked about 3.5 hours later with an undoubtedly very happy Jack Swigert aboard the Apollo 13 Command and Service Module (CSM) Odyssey. During their time apart, Swigert would have pursued his own program of Lunar Orbital Science, using a large-format Lunar Topographic Camera (LTC), known as the “Hycon.” It was a huge device, with an 18-inch (45.7-cm) lens that completely filled the window of the command module’s access hatch. Swigert would have acquired numerous high-resolution black-and-white images in overlapping sequences for use as mosaics or single frames. His key surface targets were candidate landing sites for subsequent Apollo missions, including Censorinus, the crater chain of Davy Rille and the Descartes highland site. So important was it that, after the return of Lovell and Haise, the crew were to spend another full day in lunar orbit using the Hycon and their other complement of cameras.

Barreling away from the Moon following the Trans-Earth Injection (TEI) burn at 1:42 p.m. EDT on 18 April, they were scheduled to splash down in the Pacific Ocean at 12:17 p.m. PDT (3:17 p.m. EDT) on the 21st, completing a mission of just over 10 full days. Although the Fra Mauro site was subsequently visited by the Apollo 14 crew in early 1971—thereby illustrating its significance to lunar science—it remains intensely disappointing that Jim Lovell and Fred Haise never had the opportunity to put their training and experience to the test on the Moon’s surface. It is equally disappointing that Jack Swigert lost his chance to perform exceptional lunar science from orbit. “The crewmen of Apollo 13 have spent more than five hours of formal crew training for each hour of the lunar landing mission’s ten-day duration,” NASA explained in the Press Kit. “More than 1,000 hours of training were in the Apollo 13 crew training syllabus over and above the normal preparations for the mission: technical briefings and reviews, pilot meetings and study.” Lovell and Haise also participated in 20 suited walk-throughs of their EVA activities, covering lunar geology and deployment of experiments, including the ALSEP.

Yet it must be borne in mind that, aside from the loss of a valued lunar landing mission, Lovell, Haise, and Swigert returned alive from arguably the most harrowing episode in America’s early exploration of the heavens. Against all the odds, they and a remarkable team of thousands on Earth tackled huge problems and overcame each one to snatch triumph from potential defeat. “The most frightening moment in this whole thing is when the explosion occurred and then—after a little period of time—saw the oxygen escaping and we didn’t have the solutions to get home,” Lovell told the NASA Oral History Project. “We knew we were in deep, deep trouble.”

For Apollo 13, the primary mission was lost, but in a remarkable feat of human ingenuity and courage, the mission morphed into something entirely new and continued. “I always compare this like a game of solitaire,” said Lovell. “You turn up a card, and that’s a crisis. If you can put it someplace, the mission keeps going.”

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook!

.

Ah, what might have been! Lovell always struck me as a genuinely nice guy. And there is a poignant scene in the movie, “Apollo 13,” where he tells Haise and SwI get to get a good look at the Moon as they make their free-trajectory loop. Their mission is a testament to human perseverance and ingenuity.