In 2011, Hollywood had us believe that the crew of Apollo 18 fell victim to spider-like aliens and a sinister conspiracy, spearheaded by the Department of Defense, to eliminate the chance of extraterrestrial contamination. The reality is quite different, for the men who would have flown the real Apollo 18 are alive and well to this very day, and one of them did get to walk on the lunar surface. Further, all but one of the astronauts expected to be assigned to Apollo 19 are still with us. Forty-five years ago, in the summer of 1970, NASA executed one of the most controversial—and perhaps misguided—decisions in its history, by canceling two piloted voyages to the Moon. In so doing, the space agency and a short-sighted Washington administration condemned humanity to at least two generations in which exploration Beyond Low-Earth Orbit (BLEO) was possible only with robotic craft. It was a decision, and a lost opportunity, whose echoes resonate to this very day.

Following the enormous success of Apollo 11—which saw astronauts Neil Armstrong, Mike Collins, and Buzz Aldrin become the first humans to accomplish a piloted lunar landing mission—the future for the program seemed bleak, as the Republican administration of President Richard M. Nixon, keen to seek a timely exit from the bloodbath of Vietnam and the resolution of lingering social issues at home, repeatedly made efforts to slash NASA’s budget. In February 1970, NASA Administrator Tom Paine submitted a proposal for Fiscal Year (FY) 1971 for $3.33 billion, which represented a decrease of more than $500 million on the previous year. As described by William David Compton in the NASA History tome, Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions, key savings and “hard choices” had already been achieved through the termination of the Saturn V production line, the mothballing of the Mississippi Test Facility (MTF) in Bay St. Louis, Miss., and the reduction of the workforce at the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans, La. Additionally, on 4 January 1970, NASA had formally canceled Apollo 20, which until that time might have been the final lunar landing mission.

Worse was to come. Early in July 1970, the Washington Post published a troubling article. Three months after the near-disaster of Apollo 13, it was clear that only a handful of manned lunar missions lay ahead and bumper stickers had already appeared in Florida, bearing the legend “Apollo 14: One Giant Leap for Unemployment.” The Post’s article, however, revealed publicly for the first time that as many as four Apollo missions might face the budgetary ax. After many weeks of House and Senate debate, NASA received an allocation of $3.269 billion for FY71, which necessitated the additional cutting of the Project Apollo budget by $42.1 million to a total of $914.4 million. In mid-July, NASA announced that it would reduce its workforce by 900 personnel by October. When combined with earlier layoffs and natural employee attrition, the effect brought the total number of civil service reductions in the 1968-1970 period to above 5,200, giving NASA a staff of 29,850, its lowest since 1963. By the middle of August, 175 employees were formally released and 185 others were reassigned or placed in jobs at a lower grade.

However, there existed little choice for Tom Paine—who would depart NASA on 15 September 1970 to return to General Electric—and his replacement, Acting Administrator George Low, but to significantly curtail Apollo. One option called for the execution of four of the six remaining lunar landing missions (Apollos 14 through 17), at six-monthly intervals, beginning in January 1971, before taking a break to conduct three long-duration Skylab flights in 1972-1973, then staging the last two Moon voyages (Apollos 18 and 19) in 1974. The alternative was to cancel Apollos 18 and 19 entirely and make their already-built Saturn V hardware “available for possible future uses.” One such use, NASA revealed, might be to insert a large, post-Skylab space station into orbit at some indeterminate time in the future. Even as this decision process was underway, on 28 July, Paine had tendered his resignation to Nixon. “Paine denied that NASA’s immediate funding problems had influenced his decision,” it was noted by Compton. “Probably more decisive was the fact that he saw no prospect of immediate change. From the start of his NASA tenure, Paine’s ideas for the future of the space program were far more ambitious than those of the President and the Bureau of the Budget.”

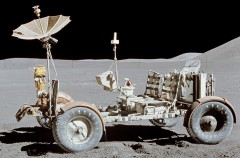

On 2 September, Paine summoned a press conference to announce NASA’s interim operating plan for FY71, in which he outlined the cancelation of Apollos 15 and 19. These flights were, respectively, the last of the so-called “H”-series and “J”-series of lunar landing missions. The former involved a short-duration Lunar Module (LM), with a stay time on the Moon of no more than 33 hours and two EVAs of approximately four hours’ duration apiece, whilst the latter encompassed a trio of EVAs—each running for five to seven hours—and up to three days on the surface, with the J-series crews assisted in their exploration by a battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), built by Boeing/General Motors. Additionally, the J-series Command and Service Module (CSM) would benefit from an enhanced Scientific Instrument Module Bay (SIMBay) of equipment for enhanced geophysical and other observations from lunar orbit. Baselined for mission durations of around 12 days, the J-series missions would mark a 20 percent duration hike over their earlier, H-series counterparts. Before the cancelations, NASA envisaged four H-series missions (Apollos 12 through 15) and four J-series missions (Apollos 16 through 19), but after the tumultuous events of the summer of 1970 the manifest changed and the remaining flights were redesignated. Apollo 14 became the last H-series mission and the newly-renumbered Apollos 15, 16, and 17 formed the new J-series. Thus, the two “lost” missions would be popularly (but incorrectly) remembered as Apollos 18 and 19.

The launch schedules for the remaining missions—the now-renumbered Apollos 14 through 17—would also be stretched out from January 1971 through December 1972. In making the announcement, Paine stressed that his decision had been made reluctantly and in spite of conclusions of several major reviews by the Space Sciences Board of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and the Lunar and Planetary Missions Board, both of which had strongly recommended that all remaining flights should have remained untouched. Paine’s main consideration, it was noted by Compton in his historical survey, was “how best to carry out Apollo to realize maximum benefits while preserving adequate resources for the future post-Apollo space program.” One saving grace was that one limited-capability H-series mission (the original Apollo 15) would be upgraded to J-series status, with a far broader scope in terms of scientific exploration of the Moon.

For many observers, though, it was not enough. The New York Times condemned the decision as “penny-wise, pound-foolish” and stressed that the “budgetary myopia” of the savings from the two canceled missions amounted to just 2 percent of NASA’s FY71 budget and a mere 0.25 percent of the total investment in Project Apollo. “Now that these huge sums have been spent,” the Times scathingly added, “the need is to obtain the maximum yield, scientifically and otherwise, from that investment.” Others, including Cornell University astronomer Thomas Gold, likened the decision to buying a Rolls Royce, “then not using it because you claim you can’t afford the gas,” whilst the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Harold Urey described the $42.1 million savings as “chicken feed” in comparison to the $25 billion already spent on Apollo. “It cost us … one half of one percent of our gross production,” Urey wrote in the Washington Post. “Now we wish to finish a job which has been beautifully began and we get stingy. Because of an additional cost of about 25 cents per year for each of us, we drop two flights to the Moon, recommended by scientific committees. How foolish and short-sighted from the view of history can we be?”

Responding to a letter from 39 lunar scientists that September, Rep. George P. Miller—then-chair of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics—pointed out that he had attempted to get an additional $220 million into the FY70 and FY71 authorization bills, but that the Nixon administration, “in realigning national priorities, has relegated the space program to a lesser role.” Rep. Miller added a mild, yet clear note of rebuke to the scientific lobby that “had your views on the Apollo program been as forcefully expressed to NASA and the Congress a year or more ago, this situation might have been prevented.”

With the cancelation of Apollos 18 and 19, the astronauts who might have performed the missions were already in place; at least, that is, in their backup capacity for other flights. Under the planning of Deke Slayton, head of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas, there existed a three-mission rotation system during Project Apollo, whereby a backup team for a given flight would move into the prime crew slot three flights later. Thus, on 26 March 1970, when the Apollo 15 crews were announced, it could be anticipated that the backups—Commander Dick Gordon, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Vance Brand, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Jack Schmitt—would rotate into the Apollo 18 prime assignment. Apollo 19 was a little harder to determine, for the prime and backup crews for Apollo 16 were not formally announced until 3 March 1971, by which time Apollo 19 had already been canceled. However, with Commander John Young, CMP Ken Mattingly, and LMP Charlie Duke already having begun training as the Apollo 16 prime crew, Commander Fred Haise, CMP Bill Pogue, and LMP Gerry Carr dug in as their backups in the summer of 1970. Had Apollo 19 survived, there is a high degree of likelihood that Haise, Pogue, and Carr would have formed its prime crew.

In the hot, violent summer of 1970—a summer haunted by President Nixon’s controversial incursion into Cambodia, despite pledges to withdraw U.S. troops, and resultant student protests, most notably at Kent State University in Ohio—the astronauts provisionally pointed toward Apollos 18 and 19 worked feverishly for a pair of missions which they knew might never come to pass. As recounted by historian Andrew Chaikin in his book A Man on the Moon, astronaut Pete Conrad had warned his buddy Dick Gordon that his best chance of another mission lay with Skylab. However, Gordon elected to persevere for a lunar landing of his own—a decision which ultimately led nowhere.

Reading between the lines of Bill Pogue’s words in his NASA oral history, the largely unspoken knowledge that the last few Apollos might vanish from the funding manifest did not make the actual hammer-blow any less devastating. “I was … put on a “phantom” backup crew, they called it, for 16,” Pogue reflected. “They did not want to announce us, and for good reason, because it looked pretty bad in Washington, as far as budget was concerned. We [went] … on geology field trips and we were out on one in Arizona. We came back to Flagstaff [and] stayed at a motel. The next morning … I walked out the door of the motel and Fred was holding this newspaper and it said ‘Apollos 18 [and] 19 Canceled’. That’s how we found out about it!” By the time the Apollo 16 crew was formally announced on 3 March 1971, Pogue and Carr had already been diverted to begin training for the Skylab program, although their official assignment would not come until January 1972. In the meantime, Fred Haise elected to remain as Apollo 16 backup Commander, joined by CMP Stu Roosa and LMP Ed Mitchell, both of whom had recently returned from Apollo 14.

Although one final Saturn V would rise to orbit after the end of the lunar program, delivering Skylab into orbit—though not without incident—on 14 May 1973, the stages and hardware of the two other vehicles subsequently and depressingly ended their days as museum pieces at JSC in Houston, the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans, La., and at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C.

From his perspective, veteran flight director Chris Kraft—who became MSC Director in January 1972 and oversaw its transition to today’s Johnson Space Center (JSC)—stressed in his autobiography, Flight, that everyone at NASA would have fought much harder to save Apollos 18 and 19 if they had known that humanity would be waiting half a century, or more, before bootprints again dotted the lunar terrain. “None of us,” he wrote, “thought that America would turn into a nation of quitters and lose its will to lead an outward-bound manned exploration of our Solar System. That just wasn’t possible.” Kraft felt that even Bob Gilruth, his predecessor as head of the MSC, who feared another Apollo 13-type failure, would have supported the additional missions, had he known that low-Earth orbit would be the only domain for America’s astronauts for at least another half-century. Meanwhile, veteran flight director Gene Kranz, in his memoir, Failure Is Not An Option, expressed similar disgust. “It was as if Congress was ripping our heart out,” he wrote, “gutting the program we had fought so hard to build.”

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Hi Ben,

Excellent article, as usual.

Particularly like the “Nation of quitters” line.

However, as much fun as blaming Nixon may be (and he certainly deserves his share), there is plenty of blame to go around.

Hope the next installment will give appropriate time to:

(1) Senator Walter Mondale (D-Minnesota)

(2) Senator William Proxmire (D-Wisconsin)

https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1955&dat=19710704&id=ko8jAAAAIBAJ&sjid=tJ4FAAAAIBAJ&pg=3572,1709561&hl=en

http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4221/ch4.htm

They certainly did more than their share, even inspiring Science Fiction writer Larry Niven to write the satirical short story – The Return of William Proxmire.

http://www.uchronia.net/bib.cgi/label.html?id=nivereturn

while I agree with the sad thesis of this article, I find your attempt to lay the Apollo program cuts at Nixon’s feet profoundly disingenuous. The Apollo missions were, deservedly or not, very good for Nixon’s approval ratings and Nixon, the MSMs/ Democrats knew it. CBS stopped covering the landings claiming it was getting complaints from soap opera viewers for preempt get their programming. While we can’t disprove this, entirely unsupported story, we do know that their Nielsen rating was significantly higher while covering the moon missions so they sacrificed viewership try not covering the missions. It was a Democrat controlled house and Senate that slashed the space program budget and, we know from letters written by congressman to NASA, that their motive was largely political. This is essential to understanding your thesis because it is the rise of the radicalized left, trial lawyers, and political correctness that has turned us into a nation of quitters.

Kevin,

As I stated in a post that for some reason appears stuck in (“Your comment is awaiting moderation.” limbo) there is plenty enough blame to go around.

I hope Part II will address the roles played by two Democrats: William Proxmire and Walter Mondale.

They certainly did more than their share, even inspiring Science Fiction writer Larry Niven to write the satirical short story – The Return of William Proxmire.

The object of Apollo was to visibly beat the Soviets, not exploration. He who signs the checks calls the tune. The tune would have suffered if there were any mishaps. There having been a few white knuckle events, the check didn’t get signed by the nervous signer as the battle was already won.

If the object had actually been to explore and develop the moon, the argument would be totally different, as would the hardware and follow up.

Ben Evans provides a bittersweet look back at the death of Apollo, one that helps underline Chris Kraft’s observation that America did, in fact, thereby become “a nation of quitters.”

The only problematic note with the narrative to date is that it seems to lay nearly all of the blame on Nixon and his senior advisers, with a supporting role for the belated response of the scientific community in coming to bat to save the final Apollo lunar missions. The problem is that it’s a narrative missing some important elements, ones that would make clearer that the causes of Apollo’s death were much more fundamental. As John Logsdon recently put it in his new book AFTER APOLLO: “The United States decided in 1970 to retreat from exploring the Moon; that decision had several parents, not just Richard Nixon.”

One of those parents was, in a way, Tom Paine himself. Evans hints at this, perhaps unwittingly, when he notes that “Paine’s ideas for the future of the space program were far more ambitious than those of the President and the Bureau of the Budget.” That’s putting it mildly. Paine was never on the same page as the Administration or the mood on Capitol Hill, where support simply did not exist for his massive plans for NASA. It was Paine’s decision, not Nixon’s, to cancel Apollo 15 and 19, which he hoped to make as easy sacrifices to further his ambitious space station and shuttle designs. In asking for the Moon and the stars, Paine unwittingly ended up with neither in the end, and killed off two more lunar missions for no tangible fiscal gain.

Which gets to the role of the other elephant in the room, the Shuttle, in killing off what remained of Apollo. While NASA had no political support for going on at the tempo it had achieved in the late 60’s, there was nothing foreordained about Nixon’s decision to support the Shuttle. The only thing that probably was inevitable was Nixon’s realization (also detailed by Logsdon) that the manned space program had enough political value in terms of jobs in key states to keep it going at some respectable (if reduced) level. But did that have to be the Shuttle? In fact, it could have been a very different, smaller shuttle, or even a continuation (on a scaled back basis) of Apollo/Saturn architecture. And had the STS not had its costs, safety and operational tempo so disingenuously presented, those other possibilities could well have been reality, given Nixon’s gradual awareness of the political value of manned space exploration.

Your assessment is also lacking.

You are leaving out the role of a very vociferous opposition to HSF on the Democratic Party left in the Congress lead by Mondale (D-Minnesota) and Proxmire (D-Wisconsin). Logsdon is a good historian, but also a very loyal Democrat and lets the latter overcome the former in this case.

It was an improbable (and unacknowledged) confluence of objectives between Nixon, Mondale and Proxmire that that produced the sad situation Ben’s article describes.

Hello Joe,

I’ll reply by repeating Logsdon’s observation: “The United States decided in 1970 to retreat from exploring the Moon; that decision had several parents, not just Richard Nixon.” Without question, congressional liberals like Mondale and Proxmire (and we might add George McGovern, Edward Kennedy, and others to that list) figured prominently along those parents. (And while we’re on the subject of mordantly satisfying sci-fi tweaks at Proxmire, we might also include Arthur C. Clarke’s “Death Comes for the Senator.)

But vexing as the almost luddite policy outlooks of these congressional liberals were, we also can’t deny that public support (as measured in public opinion polls, for example) for keeping up Apollo was already waning when Nixon came to power, and it had never been particularly strong in the first place. Proxmire and his ilk had considerable public opinion winds at their back when they joined battle to hack away at NASA’s budget. There was no way to make them go away, but a savvier NASA leadership could have mitigated their effectiveness with more realistic and more prudent plans for NASA’s future. Too often, NASA has been its own worst enemy. Apollo, in a way, spoiled it by creating a corporate culture that always assumes it can win acceptance of politically and fiscally unsustainable programs.

Hi Richard,

We do not really disagree on this.

The fact is that there was never a “Golden Age” when majorities of the public supported space programs. The only time support went above 50% was in one Gallup Poll run immediately after Apollo 11.

What is also true is that on average over the decades in the range of 40% to 45% have supported it. This in spite of the fact that some of the same polls (the ones that bothered to ask) show those same people think the program costs some 20 times what it actually does.

The real question is whether or not that consistent 40% to 45% plurality could/should be able to determine what no more than 1% of the federal budget should be (the current NASA Budget is about 0.4% of that budget).

Your comment about the “almost luddite policy outlooks of these congressional liberals”, shared by some on the right, (in my opinion) is the source of the problem.

During the 1990’s I had occasion to deal with people who were working on the Centrifuge Module to the ISS. They worried constantly that certain members of Congress would realize that the Module (in addition to the esoteric “pure” science goals they were advertising) would also contribute to learning how to build space based close looped life support habitats. The Centrifuge Module was eventually cancelled, for strictly fiscal reasons of course.

Even if some scaled back Apollo and/or smaller Shuttle could have been fitted into the drastically reduced NASA Budget of the early 1970’s, the Proxmire/Mondale contingent would have opposed it just as vociferously; for strictly fiscal reasons of course.

“…the Proxmire/Mondale contingent would have opposed it just as vociferously; for strictly fiscal reasons of course.”

Oh, absolutely.

Nonetheless, NASA has in each boxing round (Apollo Applications, the Space Task Group proposals, the Shuttle, Freedom, SEI, VentureStar, Constellation, and now SLS) made their job easier by pushing ambitious programs, which it usually lowballs on cost and oversells in capabilities. Paine’s program in 1969-70 is a case in point. The more expensive your program, the higher a radar profile you make it for congressional gunners to shoot at. The original TOPS probes proposal to do the “Grand Tour” of the Outer Solar System was estimated at most of a billion dollars. Congress killed it promptly. When JPL came back with the Voyagers for only $250 million, it passed fairly easily.

The real political support that has sustained NASA’s manned space program isn’t in the opinion polls, but the network of NASA facility and aerospace contractor jobs LBJ set up in key congressional districts to ease Apollo’s passage. Nixon eventually figured this out. The problem for NASA in 1969-1972 was to determine what kind of program that network of congressional support could actually sustain. What it eventually came up with was the Shuttle. But it is reasonable to think that it could also have been there to sustain, say, a scaled back Apollo Saturn-based program, probably centered around Skylab-based LEO space station(s) – after all, that wouldn’t have cost nearly as much in development costs as STS did, and unlike STS it would have been evolvable (nor would it have had any six year gap in space flight). And it couldn’t have been any easier for Proxmire and friends to kill than STS was.

P.S. It is a great pity that the Centrifuge Module was killed – it was easily the most valuable research component of the ISS.

“But it is reasonable to think that it could also have been there to sustain, say, a scaled back Apollo Saturn-based program, probably centered around Skylab-based LEO space station(s) – after all, that wouldn’t have cost nearly as much in development costs as STS did, and unlike STS it would have been evolvable (nor would it have had any six year gap in space flight). And it couldn’t have been any easier for Proxmire and friends to kill than STS was.”

A several points:

(1) It probably would not have been sustainable under the yearly budget restrictions given. As in order to get the NASA budget down to the prescribed budget levels (in the specific fiscal years in question – something being forced by Proxmire), required shutting down too much of the Apollo/Saturn manufacturing infrastructure (i.e. specific facilities).

(2) It is also (in my opinion) a mistake to think that the shuttle hardware is not evolvable. I am familiar with the approaches considered in the 1969/1970 time frame to modify the Apollo/Saturn Hardware to support future capabilities, but it would have cost more than the year to year budget caps being imposed by the Congress (read Proxmire) to achieve. But similar evolutions of shuttle based hardware were/are possible. In fact the SLS (however compromised by current politics) is exactly that.

Do not get me wrong if had anything to say about the post Apollo decisions, I would have supported the evolutionary approach you are talking about. Unfortunately, I was (to paraphrase the Warren Oates character from the old movie “Blue Thunder”) “sitting in front of the TV Tube, watching Bugs Bunny Cartoons, and sucking on my fudge cycle”.

I am just hoping (though I am not very hopeful) we are not being forced by other anti HSF politicians now into making the same stupid decisions again.

Hello Joe,

Re: Apollo/Saturn prospects: It depends on how you structure it. I doubt you could have kept building Saturn V’s – certainly no more than a handful, at any rate. The real focus would be using up what hardware remained, and developing a more cost effective successor to the Saturn IB, along with an unmanned cargo vehicle to keep the station(s) supplied (both far cheaper to develop than STS was)…and a slowly evolving Apollo CSM. Keep in mind we ended up with a spare Skylab, 2 Saturn V’s, 5 Saturn IB’s, and a few Apollo CSM’s that ended up as expensive museum exhibits – you have a fair bit of hardware already built and paid for to buy you time up through the mid-70’s. One (fairly detailed) exploration of what such a program might have looked like, assuming historic NASA budgets, was one recently worked by a couple of young aerospace engineers called “Eyes Turned Skywards” – worth a look: http://wiki.alternatehistory.com/doku.php/timelines/eyes_turned_skyward

I can’t see how the STS we ended up with could possibly have been evolvable, not on our historic budgets – it was built as a mature, complete system, which only ended up with modest avionics and other system upgrades over time. What was possible was what Logsdon suggests: a more modest, crew only shuttle, something much cheaper to develop and fly, and ultimately replace (and on which non-manned cargos would not have been dependent). In particular, in 1971 President Nixon’s science adviser, Edward David, convened a panel chaired by Alexander Flax to review the Shuttle’s development and produce recommendations on how to proceed. When the Flax Committee issued an interim report in October 1971, they showed skepticism that the then-planned Shuttle program (which by that point generally resembled the OTL program) was achievable or practical (Flax noting that “members…doubt that a viable shuttle program can be undertaken without a degree of national commitment…analogous to that which sustained the Apollo program…certainly not now apparent”), and instead recommended that NASA develop a small “glider” that would be launched on top of a Titan IIIL (a wide-body version of the Titan), with a payload of perhaps 10,000 pounds, in effect a shuttle very much like the HL-42

It’s certainly a possibility that could have stood closer examination.

Instead, we ended up with the Shuttle. A marvelous machine in many ways, but too far too ambitious for available budgets and technology, and therefore fatally hedged with compromises. Some of them ultimately fatal.

Richard,

No variation of evolved Apollo/Saturn hardware could have survived the early 1970’s budgets, because they were designed to force the shut down to the hardware production lines. The Shuttle could survive it because during that period it was only a Phase A Study. Undoubtedly the Proxmire/Mondale contingent in the Congress (and perhaps Nixon as well) thought that once Apollo was history Shuttle would be canceled as well (before actual hardware work was begun). But for various reasons (probably including Watergate) Shuttle survived. To use Apollo/Saturn hardware later in the 1970’s/1980’s would have required restarting all the specific production lines. A very expensive and time consuming process (if it could be done at all), which of course was the exactly the idea.

The evolution of the shuttle hardware would involve (among other things) development of a Shuttle Derived Heavy Lift Vehicle (SDHLV)such as the Block I SLS. The Block I SLS (with the proper upper stage) will be able to put around 90 Metric Tons into orbit. There has been evaluation done of that same configuration without the SRB’s that would have a 50,000 lb. to LEO capability (a sort of Saturn IB equivalent). It would be interesting to see what the costs would be to run a program based on those “two” vehicles with all their common components/infrastructure.

The Obama Plan put forward in 2010 intended to try the same thing as was done to Apollo/Saturn to the Shuttle. That is shut down the whole industrial infrastructure in such a way that it could not be revived and (in this case) replace it with a vague promise to do (bold, innovative, world class, game changing, paradigm shifting, 21st Century – did I leave any superlatives out) research into undefined breakthrough technologies. Then, no doubt, shut the whole thing down after the Shuttle industrial base was gone. Even the 2010 Congress (overwhelmingly controlled by the Democratic Party) would not buy that and forced the acceptance of the SLS on Obama to keep the industrial base at least on life support.

Which is where we are now.

That brings us to the real question. Assuming we eventually get some kind of capability again what are we going to do with it. James (I think) hits on the answer in his post below (August 16, 2015 at 4:38 am). Lunar Return with the intent of developing Lunar Resources. These can be used to eventually support Mars Missions, but also (and I think more importantly in the short run) support for Applications Platforms in Cis-Lunar Space with direct benefit to current terrestrial society.

The records from the White House and NASA are fairly clear – at least to me…

Apollo was seen as the race to beat the Soviets. A very risky undertaking. Many in NASA were happy to end it – the LEM in particular was considered to have very high LOC numbers.

Shuttle was seen as the return to the what-would/should-have-been – X20, Von Braun/Colliers etc. This would enable routine operations in space at a greatly reduced cost. If this had occurred to the extent that was believed at the time, a Shuttle supported moon program would have been relatively cheap.

Hello Joe,

I can’t help but think you’re overstating the political opposition to manned space in the early 70’s. If it was powerful enough to have shut down any continued Apollo program, it was surely enough to kill any expensive new shuttle program in the crib. Yet it didn’t. If anything, developments like Watergate should have made it easier to scuttle, not harder. Again, the real support base for NASA at this point were the jobs in key districts, which is the sort of thing that makes government programs very hard to kill off. (Proxmire’s real successes were against small programs and ledger items without sufficient congressional footprints.) The revival of Constellation after Obama’s kill-off is a good demonstration of this reality. Killing off Constellation made some good sense, given that it was utterly unsustainable; but the failure to replace it with something that might be sustainable (and keep most of those jobs in place) was not going to fly on Capitol Hill, certainly not without an investment of political capital that Obama was unprepared to expend.

A Shuttle Derived Heavy Lift Vehicle was certainly a plausible development of STS hardware – but only of the launch vehicle system, not the orbiter, which is what I was really addressing. The Shuttle orbiter was a finished vehicle; because it was “reusable” (a word I use generously), it could not evolve in design like a disposable capsule or rocket could, given that it was far too expensive to simultaneously operate and replace with more capable successors. All that said, the failure to pursue an SDLV back when the production lines and tooling were still open was a missed opportunity. Certainly it would have been a way to salvage something worthwhile from STS.

Hello Malmesbury,

“Many in NASA were happy to end it – the LEM in particular was considered to have very high LOC numbers.”

That’s a good point that has not been addressed – and one more reason why any continuation of Apollo was likely to be more viable in a pullback to Low Earth Orbit for the time being (and the idea of Venus or Mars flybys especially far-fetched). Certainly Apollo had a number of very close calls. That said, it does make Chris Kraft’s comment at the end of the article rather curious, given that he was one of the principal NASA officials who shared this concern. Was this a case of regretful second thoughts?

Of course, the key reason why Apollo died was cost, not safety, and pretty much all accounts of the program seem to agree on that. But you’re correct that some were not unhappy to unload the high risk that it represented, given the available technology and hardware.

Richard,

“I can’t help but think you’re overstating the political opposition to manned space in the early 70’s.”

I don’t think I am, especially when you take into account Proxmire’s position on a key committee controlling NASA’s budget.

What ever else you think of Proxmire, he was a master of budgeting and crafted limits in specific funding area’s so that it can be suspected a lot of his colleagues did not fully realize what they were voting for. Never the less the required shut down of the Apollo/Saturn hardware was built into the budgets and not pushed back on by the Nixon Administration.

That is what I meant about Watergate. With Nixon gone, the Ford Administration (while not overly friendly to space) played a “straight game” with NASA allowing the Shuttle to survive.

The Congress did not/could not “revive” Constellation, they did manage to keep part of the existing industrial infrastructure in place with SLS.

As for Constellation being “unsustainable”, that has become a buzz phrase without real meaning. Even if you accept the idea (promulgated by the administration) that Constellation would require an extra $3B/year to work that is about 0.09% of the Federal Budget (one penny out of every ten tax dollars). Constellation was “unsustainable” strictly because Obama did not want it sustained.

Malmesbury,

While I am sure it is true that some in NASA (particularly in management) were relieved to have the risk of the Apollo missions gone, nobody was talking about flying Apollo style sorties beyond Apollo 20; it is really extraneous to the subject of whether the best way to replace Apollo was with Shuttle or new vehicles evolved from Apollo/Saturn Hardware.

Hello Joe,

Just a few comments, perhaps my last, I hope:

(1) “… the required shut down of the Apollo/Saturn hardware was built into the budgets and not pushed back on by the Nixon Administration.” Naturally, because NASA and OMB did not want to jeopardize Shuttle development; if that was the price they had to pay to go ahead with a Shuttle program, so be it. For the same reason, NASA decided against asking for funding to launch and operate the Skylab B in 1976, which seemed too likely to crowd available funding. NASA had put all its chips in the Shuttle basket.

(2) “With Nixon gone, the Ford Administration (while not overly friendly to space) played a “straight game” with NASA allowing the Shuttle to survive.” This only makes sense if a Nixon Administration with no Watergate that survived to the end of the term would have had greater difficulty, or less willingness, to stay the course on Shuttle funding. But all the evidence is that Nixon did. And NASA’s shuttle budget continued to surge, even as its manned space flight budget started rising again: $475,000 in FY 1974, $797,500 in FY 1975, and $1,206,000 in FY 1976 (Ford’s first budget). And to the extent that Proxmire aimed public fire at the STS in that period, it was mostly, as far as I can make out, at DoD’s role in it (he claimed, not without some cause, that DoD’s enthusiasm for the Shuttle was tepid and forced).

(3) On Constellation: I think it’s quite reasonable to gloss SLS as the resurrection of Constellation, given that it’s making use of so much of its hardware (the Orion, the SRB’s, the J2-X, much of the avionics and tooling, etc.), even if it’s stripped of the latter’s planned objectives. Either way, Constellation was unsustainable on NASA’s existing budgets, despite Griffin’s promises to the contrary. A $3 billion funding increase for NASA (even assuming that were enough, which is highly questionable), which would have amounted at the time to a 20% increase in NASA’s total budget, was simply not realistic, not for an agency whose funding has remained static in real terms over the last three decades (once you subtract the construction of Endeavour as Challenger’s replacement in FYs 1988-91), over administrations and congresses controlled by both parties. It wasn’t just the Administration which was calling it unsustainable, it was the Augustine Commission as well. “Under the FY 2010 funding profile, the Committee estimates that Ares V will not be available until the late 2020s” – and that was assuming the $3 billion funding boost every year.

Obama didn’t want to spend the extra money but neither did Congress, and that had been just as true during the Bush years. If NASA wants to do any manned exploration beyond Earth orbit, it’s going to have to do it working out of existing funding levels; if it needs more money it must cut some other program. The political support is there to keep that budget static, but not to increase it. I wish it were otherwise, every much, but that’s the reality we face.

Richard,

This is rapidly devolving into a pedantic back and forth, restating original positions with newly selected details to reinforce originally stated positions.

I can keep that up as long as you can, but have no desire to do so, as it will not accomplish anything. I will not change your mind nor you mine and everybody else will just be bored.

As far as the facts are concerned I do not even think there is that much difference between our positions just how they are interpreted.

In this case I do not have to hope, this will be my last comment on the subject.

Works for me, Joe.

We differ on some things, but not really that much on why Apollo died.

One might consider the Saturn IB, or even Russia’s new Angora 5, and wonder what could have been the usefulness of a similar type of launch vehicle based on clustering first stages of the Titan and using LR-87-3 kerolox rocket engines or LR-87 LH2 hydrolox rocket engines.

The Space Shuttles accomplished much and the International Space Station exists for a diversity of research. The SLS and International Orion should be reliable, useful, and affordable.

However, in an alternate reality, not building the Space Shuttles, keeping the Apollo spacecraft and “developing a more cost effective successor to the Saturn IB” and using dual, or more, NASA launches for international human and robotic Lunar missions that occurred every two or three years might have enabled an early discovery of the water and other frozen volatiles that are available in the Moon’s cold polar regions.

And as was noted by Dr. George Nield, an associate administrator for the Federal Aviation Administration, “Once we are able to extract water and various minerals from the Moon and other heavenly bodies, it will have a tremendous synergistic impact on our ability to explore the solar system and establish a true space economy.”

Safety is another key issue. Both Apollo 1 and Apollo 13 clearly demonstrated the ongoing risks of attempting to prepare for and do beyond LEO human spaceflight. Today, most folks have access to the Internet and it is difficult to maintain political support and public funding for a nationally and internationally high visibility and very risky US government activity.

Tapping Lunar resources should eventually enhance both the frequency and safety of beyond LEO spaceflights.

Another aspect to the high risks of beyond LEO spaceflights are the many consequences of doing international Lunar missions.

If the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project LEO mission had resulted in a fatal disaster of some kind, we might have said the astronauts and/or cosmonauts died while trying to create trust and improve the tense relations between two countries that were involved in an often hot and deadly Cold War.

Building international trust is extremely hard and yet it is an activity needed both here on Earth and on the Moon. International politics played an essential role in getting us to the Moon and in building and maintaining the International Space Station. One should not ignore or underestimate the role international politics will play in developing the motivation and tools needed to efficiently tap the Moon’s resources.

Yikes! Angara 5 not “Angora 5”.

An important distinction. I do not believe a lanolin/LOX engine would work too well.

In March of 1971 I was told I was being laid off. They say they were sorry to have to lay me off but they had an alternate solution. They said if I wanted to I could transfer to Vietnam to work installing communication equip. Naturally I turned them down. But that shows you where their priority’s were. Plenty of money for war but not for space travel. BTW I didn’t work for NASA I worked for a contractor like most other workers did. I worked for FEC Federal Electric Corp which took care of all the communications.