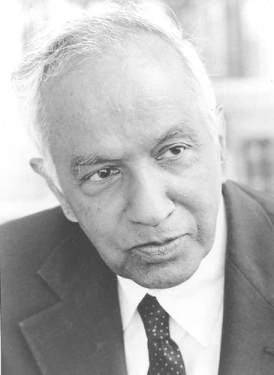

Twenty years ago, this week, NASA opened a worldwide contest to name its third Great Observatory, devoted to X-ray studies of the Universe. Previously known as the Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility (AXAF), the agency announced that it was looking for the name of a non-living person, place or thing, “from history, mythology or fiction”, with applicants asked to supply a few sentences about the relevance of their proposal to the mission. The naming would bring AXAF in-line with its sister observatories, the Hubble Space Telescope and Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, respectively named for astronomers Edwin Hubble and Arthur Holly Compton. Eight months later, after receiving 6,000 submissions from across the United States and 60 other nations, NASA selected the name “Chandra”, honoring Indian-born Nobel Prize-winning scientist Subramanyan Chandrasekhar (1910-1995), widely recognized today as the father of modern astrophysics.

In its initial call for proposals, dated 16 April 1998, NASA requested that the name should not have been used on previous space missions by any other organization or nation and offered a trip to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida to witness its launch aboard the Space Shuttle as the grand prize. All told, 59 individuals submitted Chandrasekhar’s name and the joint winning essays, chosen at random, were by student Tyrel Johnson of Priest River Lamanna High School in Priest River, Idaho, and physics and astronomy teacher Jatila van der Veen of Adolfo Camarillo High School in Camarillo, Calif.

“Chandrasekhar calculated the maximum mass for a white dwarf start and the increase in electron degeneracy pressure as a white dwarf star contracts under gravity,” explained Johnson in his submission, “and he did it all on a Brunsviga calculator over a period of about four or five months.” Johnson added that Chandra’s book The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes was a tool “with which anyone should be able to make calculations for any black hole perturbations they desire”, concluding that his work on the proof of a maximum mass for white dwarf stars “first led scientists to really look for other stellar graveyards, neutron stars and led to the inevitable conclusion that implosion is compulsory”.

Van der Veen’s essay pointed to the Chandrasekhar Limit of 1.4 solar masses, identified by Chandra as the greatest possible mass for a white dwarf star. “He was a courageous pioneer in astrophysics,” van der Veen wrote. “Chandra means moon in Sanskrit; it is depicted in the hand gestures of BharataNatyam, the classical dance of South India, as a crescent moon, and is also used to indicate the passage of time as shown by the changing phases of the moon. I think this connotation, as well as being part of the name of a very prominent astrophysicist whose research on high energy astrophysical phenomena was crucial to our understanding of neutron stars and black holes, makes Chandra an appropriate name for the AXAF satellite.”

On 21 December 1998, the seven-member selection committee made its final decision and NASA announced that AXAF would be renamed as the “Chandra X-ray Observatory”. It was noted that this was a shortened version of Chandrasekhar’s given name, and one which he preferred to use among close friends and colleagues. Additionally, Chandra also means “moon” or “luminous” in Sanskrit. “Chandrasekhar made fundamental contributions to the theory of black holes and other phenomena that the Chandra X-ray Observatory will study,” said then-NASA Administrator Dan Goldin. “His life and work exemplify the excellence that we can hope to achieve with this great observatory.” Added Britain’s Astronomer Royal, Prof. Martin Rees: “Chandra probably thought longer and deeper about our Universe than anyone since Einstein.”

Born in Lahore, in the Punjab, within what was then British India, Chandra’s father was deputy auditor-general of the Northwestern Railways. He was home-schooled until the age of 12, after which he exhibited an early interest in astronomy, eventually earning his degree in physics from Presidency College, Madras, and traveling to Cambridge in the United Kingdom for postgraduate study. He gained his doctorate in 1933 and began a lengthy scientific career, emigrating to the United States in 1935 and serving the next half-century on the faculty of the University of Chicago. He won the Nobel Prize in 1983 for his contributions to astronomy and established himself as the widely-labeled “father” of modern astrophysics. Chandra’s valuable theoretical work on stellar evolution established a basis for the existence of neutron stars and black holes—the very objects which the Chandra X-ray Observatory would observe from its high orbit—and his wife, Lalitha, later recalled his passion. “Chandra thought black holes were the most beautiful things in the Universe,” she said later. “I hear a lot of people say they are bizarre, they are exotic, but to Chandra they were just beautiful.”

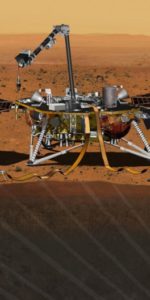

The expedited nature of the naming of Chandra, from the call for suggestions in April 1998 and the formal selection in December, was not mirrored by the observatory itself. Originally targeted for launch aboard shuttle Columbia on STS-93 in the fall of 1998—as the first human space mission ever commanded by a woman—the launch was repeatedly pushed back by technical problems, firstly into the late spring of 1999 and eventually into late July. Many of the problems, as noted by prime contractor TRW of Redondo Beach, Calif., centered on the observatory itself, including issues with faulty copper circuitry on printed circuit boards, troubles with electrical capacitors and the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster which would deliver it from the shuttle’s payload bay into a highly elliptical orbit, sweeping as close as 6,200 miles (10,000 km) and as far as 87,000 miles (140,000 km) from Earth.

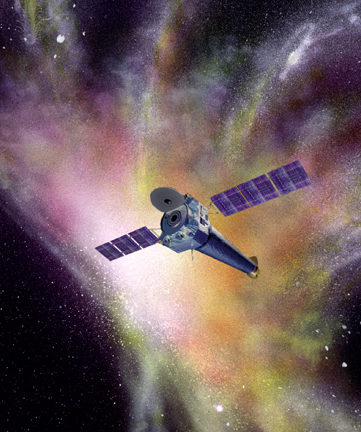

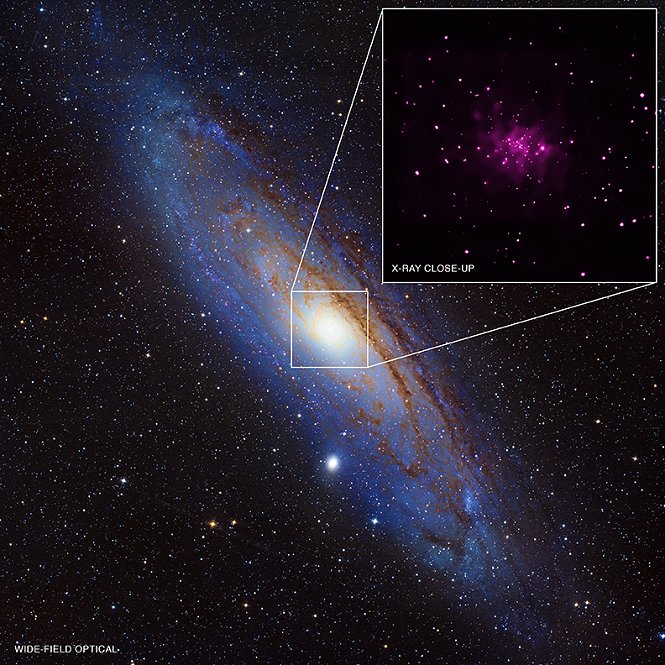

This orbit was necessary for Chandra’s observations, but also meant that the $1.5 billion spacecraft was entirely out of reach of shuttle astronauts in the event of failures after deployment. Finally launched in July 1999, it tipped the scales as the largest and heaviest payload yet launched by the shuttle, filling 57.1 feet (17.4 meters) of Columbia’s 60-foot-long (18.3-meter) payload bay envelope and weighing in excess of 49,800 pounds (22,600 kg). Passing 15 years of operational service in July 2014, Chandra enabled unique perspectives of activity in the hottest and most energetic regions of the Universe and permitted observations of stars, galaxies, quasars, supernovae, black holes and even planets and comets in our Solar System. Additionally, wrote AmericaSpace’s Paul Scott Anderson, it added to our understanding of dark matter and dark energy.

Twenty years since the campaign to name Chandra first began, it continues to perform ground-breaking science, as part of the remaining fleet of Great Observatories, which presently includes Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope; Compton having been deorbited back in June 2000. “Chandra changed the way we do astronomy,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s Astrophysics Division in Washington, D.C., speaking in 2014. “It showed that precision observations of the X-rays from cosmic sources is critical to understanding what is going on.”

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook!

.