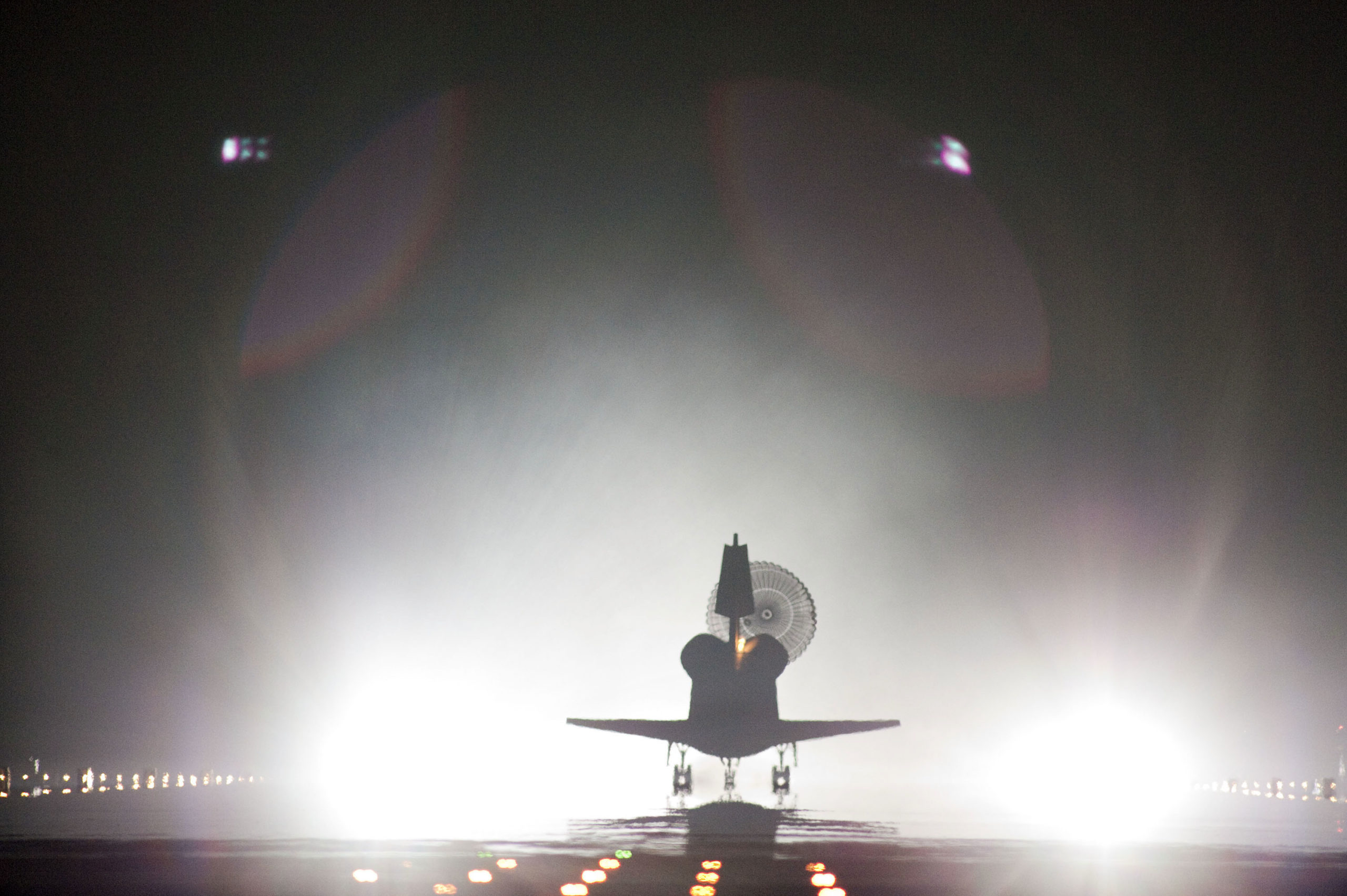

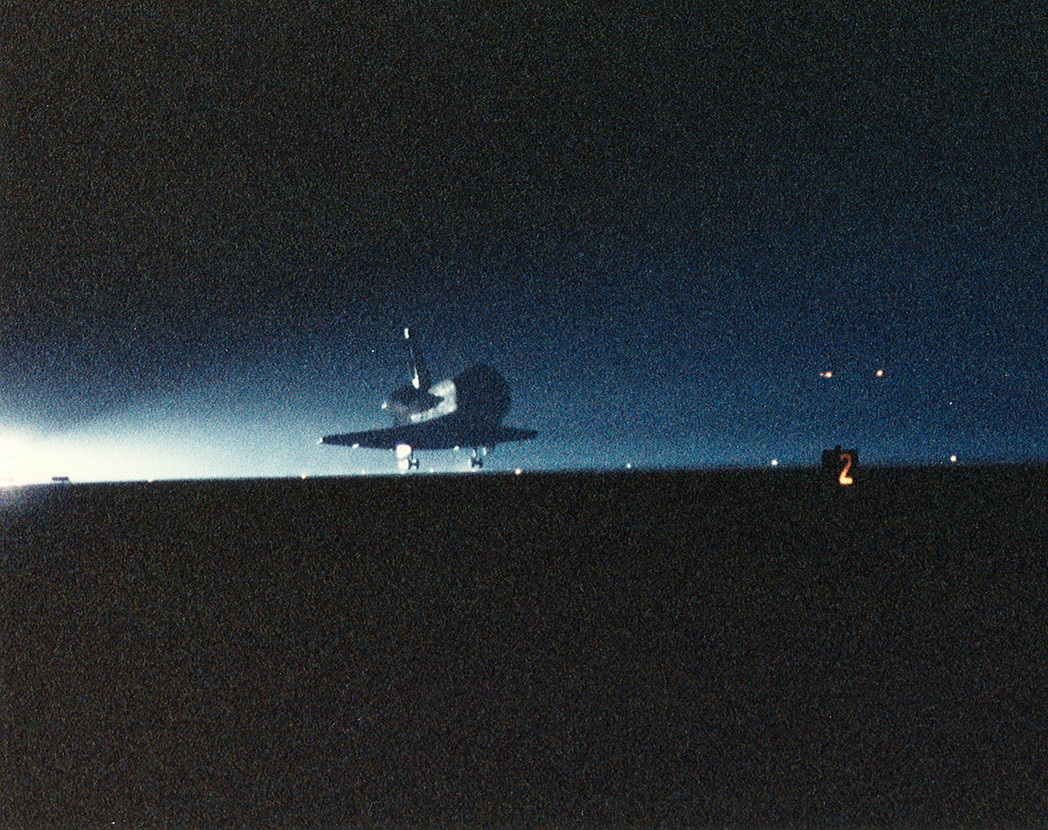

Throughout its 30 years of operational service, America’s Space Shuttle program accomplished no less than 26 landings in the hours of darkness. Characterized by NASA as missions which ended no later than 15 minutes before sunrise, these “night landings” put their astronaut crews and trainers to the ultimate test, without the usual visual cues afforded by bringing the shuttle back to Earth in daylight. All told, between STS-8 in September 1983 and STS-135 in July 2011, no fewer than 130 men and women from eight nations made landfall aboard the shuttle at night. And three of them—seasoned veterans Steve Hawley, Jim Newman and Joe Tanner—did so three times across their astronaut careers.

As outlined in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, it was Challenger which made the first shuttle night landing at 12:40 a.m. PDT (3:40 a.m. EDT) on 5 September 1983. Sadly, her untimely loss a little over two years precluded her from repeating the feat, but her four spacefaring sisters—Columbia, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour—would do so multiple times, with Discovery logging eight night landings, Endeavour seven and Columbia and Atlantis five apiece. Each of her crews had their own stories to tell about returning from space and alighting on terra firma in the darkness.

The shuttle’s second night landing was made by Columbia at the close of STS-61C on 18 January 1986, just ten days before the destruction of Challenger. Returning to Earth a couple of days late, when bad weather forestalled hopes of landing at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida and the crew was eventually directed to Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., after a mission seemingly snakebitten by cruel fortune. Those doubts over where they might land had already caused some light-hearted amusement for the astronauts, who even cobbled together a mock song—sung in two-part harmony by Commander Robert “Hoot” Gibson and Pilot Charlie Bolden—to the tune of “Who Knows Where Or When?”

But the changed landing site was perhaps most frustrating for one of 61C’s crewmen, Florida congressman Bill Nelson, who had hoped for a photo-opportunity taking a Florida orange upon touchdown. Landing in California scuppered those plans and the recovery crew, led by STS-8 veteran Dan Brandenstein, showed no mercy. They presented the astronauts with a basket of California oranges and grapefruits from the California Growers’ Association, a joke that Nelson did not appreciate. Interestingly, STS-61C was originally targeted for a daytime landing, but Gibson wanted his crew to be ready for all eventualities. “Everything worked, except God!” joked Bolden in his recollections for the NASA Oral History Project. “Hoot, in his infinite wisdom, had decided that half our landing training was going to be nighttime, because you needed to be prepared for anything.” And on 18 January 1986, anything definitely showed up.

In spite of an overcooling water-spray boiler during re-entry, their return to Earth went well and Gibson brought Columbia smoothly onto concrete Runway 22 at Edwards, rather than the dry lakebed Runway 17. “At night, we don’t put it on the lakebed because it stirs up all the dust and that blocks the xenon lights,” Gibson told the NASA oral historian. “Night landings always have to be on a hard-surface runway. My first landing, the first time I got my hand on the control stick to feel it out in atmospheric flight, would up being an unplanned night landing. It went fine.”

Brandenstein made the next shuttle night landing on 20 January 1990, when he brought the heavyweight Columbia back to Edwards at the end of STS-32, laden with the newly-recovered Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) satellite. “Watching a shuttle land at night is not a great spectator sport,” he joked in the post-flight press conference, “because you don’t see anything until the last couple of seconds as you pop out of the darkness and into the light.

Even landing at Edwards, with its wide expanse of runway for added safety, posed acute challenges. “If you’re landing at Edwards in the daytime, out of the corner of your eye you can see the sagebrush and it’s giving you an impression of how high you are above the ground,” recalled STS-35 Commander Vance Brand of landing Columbia in December 1990. “But at night, you’re really relying on light patterns that you see.”

The view from inside the orbiter as it re-entered the atmosphere in the darkness was particularly impressive. From his seat on Columbia’s flight deck during STS-35, Mike Lounge saw waves of superheated plasma rippling across the flight surfaces in a rainbow of colours, from reds and oranges to yellows and pinks. “That entry was a little more colorful, because it was in the dark,” Lounge later told the NASA Oral History Project. “The landing itself was hard to see. So I hoped Vance was going to the right place!”

When Frank Culbertson and Bill Readdy landed Discovery at KSC for the first time in the hours of darkness in September 1993, their STS-51 rollout afforded onlookers additional excitement, due to an earlier-than-planned shutdown of an Auxiliary Power Unit (APU), which visually manifested itself in the form of burning plumes from the orbiter’s port-side exhaust ducts. Although seen on earlier missions, and not considered abnormal, the occurrence of the plumes in the hours of darkness proved somewhat dramatic in itself.

“One of the APUs…was extremely visible, and at first it looked as though we had a landing light on, because it was making an awful lot of visible light,” Readdy told the NASA Oral History Project. “When you see infrared views of the shuttle, you can see the exhaust of the APUs and you can see how hot the brakes get and the tires and everything else. In this case, just the regular television camera is showing the base of the tail and there’s this fire coming out of it. They were anxious for us to get that one shut down expeditiously, but it wasn’t any big deal. Just hadn’t ever seen that before. That was a normal phenomenon for landing at the Cape at night. Wouldn’t ever see that in the daytime.”

Four of the five Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing missions terminated at night. In December 1993, during the STS-61 descent, Commander Dick Covey remembered passing high above Mexico City during peak aerodynamic heating. “The orbiter was fully enveloped in the ionization plume and as we banked up into a left bank coming over Mexico City, the windows were white because of the plume,” he told the NASA Oral History Project. “I could look out and still see all the lights. It was not washed-out at all; it was very bright through that, so we had to be giving them a great show.”

Three years later, in February 1997, during the return from the second HST servicing mission, Discovery swept across the entire continental United States and appeared as a bright streak as it passed over the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas. “You lit up the entire sky with the orbiter and its trail,” Capcom Kevin Kregel told STS-82 Commander Ken Bowersox. “It was a pretty good view from here, too,” replied Bowersox. “We almost saw the Astrodome!”

Landing that mission was also aided for the first time by the presence of 52 halogen lights, positioned at 180-foot (60-meter) intervals along the runway centerline, which gave Bowersox “a good feel” during the rollout of where he was.

The landing of the third Hubble mission in December 1999 produced such a spectacular light show that the Shuttle’s plasma trail was visible to skywatchers from South Texas to New Orleans, La., and even the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. And when Scott Altman brought Columbia smoothly onto the KSC runway in March 2002, to wrap up the fourth visit to Hubble, landing at night had become simply fun. “That landing was so much fun,” Altman told the post-flight press conference, “that you just want to do it again!”

Between STS-88 in December 1998 and the final shuttle mission, STS-135 in July 2011, no fewer than 14 International Space Station (ISS) construction flights also terminated in the hours of darkness. So too did Columbia’s ambitious July 1999 voyage to deploy the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which was led by the first female shuttle commander, Eileen Collins. “Night landings are a little more difficult,” she acquiesced, adding that “obviously; you don’t have the same depth perception or sense of speed at night”. That said, Brent Jett—who landed Endeavour at night on STS-97 in December 2000—stressed the sentiment of many of his fellows in having no difficulty bringing the shuttle down to the runway in either daylight or darkness. “You point the nose of the orbiter down,” he quipped, “and you’re gonna land!”

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

How is Discovery’s STS-128 considered a night landing; landing locally at 5:53PM, with sunset at 7:02PM?