Northrop Grumman Corp. has announced its intent to donate a pair of flight-worthy Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) to join Space Shuttle Endeavour and a “real” External Tank (ET) at the California Science Center (CSC) in Los Angeles, Calif. When fully erected in an upright position—forming the centerpiece of the CSC’s future Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center—the exhibit will mark the world’s only existing “stack” of a genuine shuttle, tank and boosters in their ready-to-launch configuration, anywhere in the world.

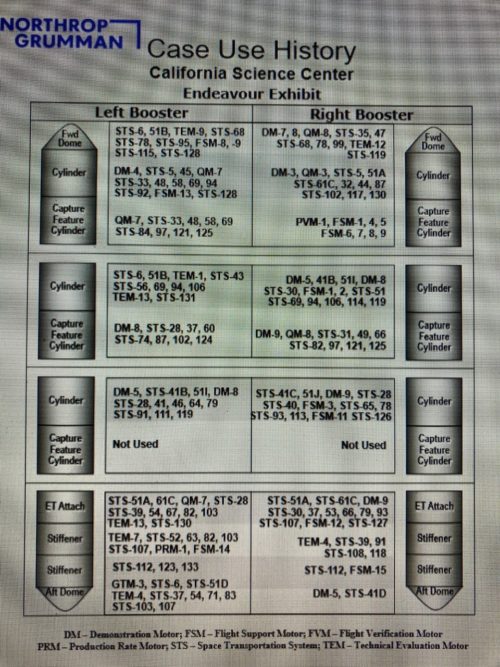

“CSC arranged for the boosters to be transported by truck from Promontory, Utah, to storage,” Northrop Grumman’s Kay Anderson told AmericaSpace, “where they will be until CSC is ready to mate them with the orbiter.” Although never flown as a complete SRB “set” on an actual shuttle flight, parts of the two boosters flew on 15 Endeavour missions between 1992 and 2010.

Endeavour, the youngest of NASA’s fleet of five reusable orbiters, flew 25 times between May 1992 and June 2011, totaling over 299 days in space, more than 4,600 orbits of the Home Planet and nearly 123 million miles (198 million km) traveled.

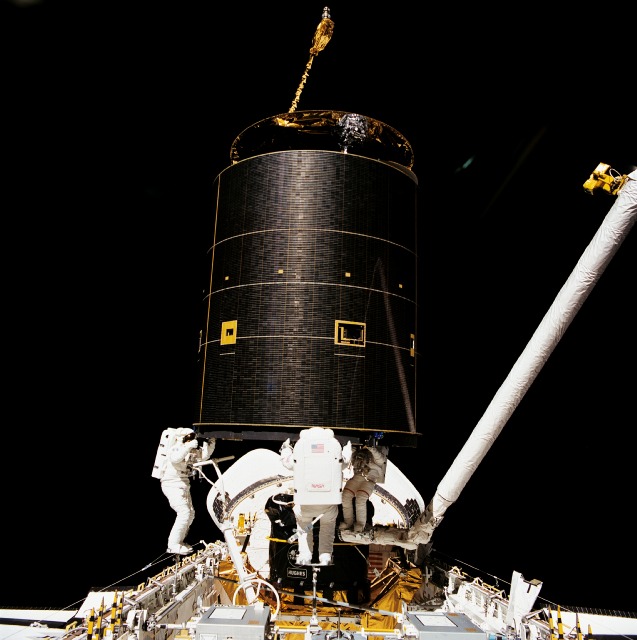

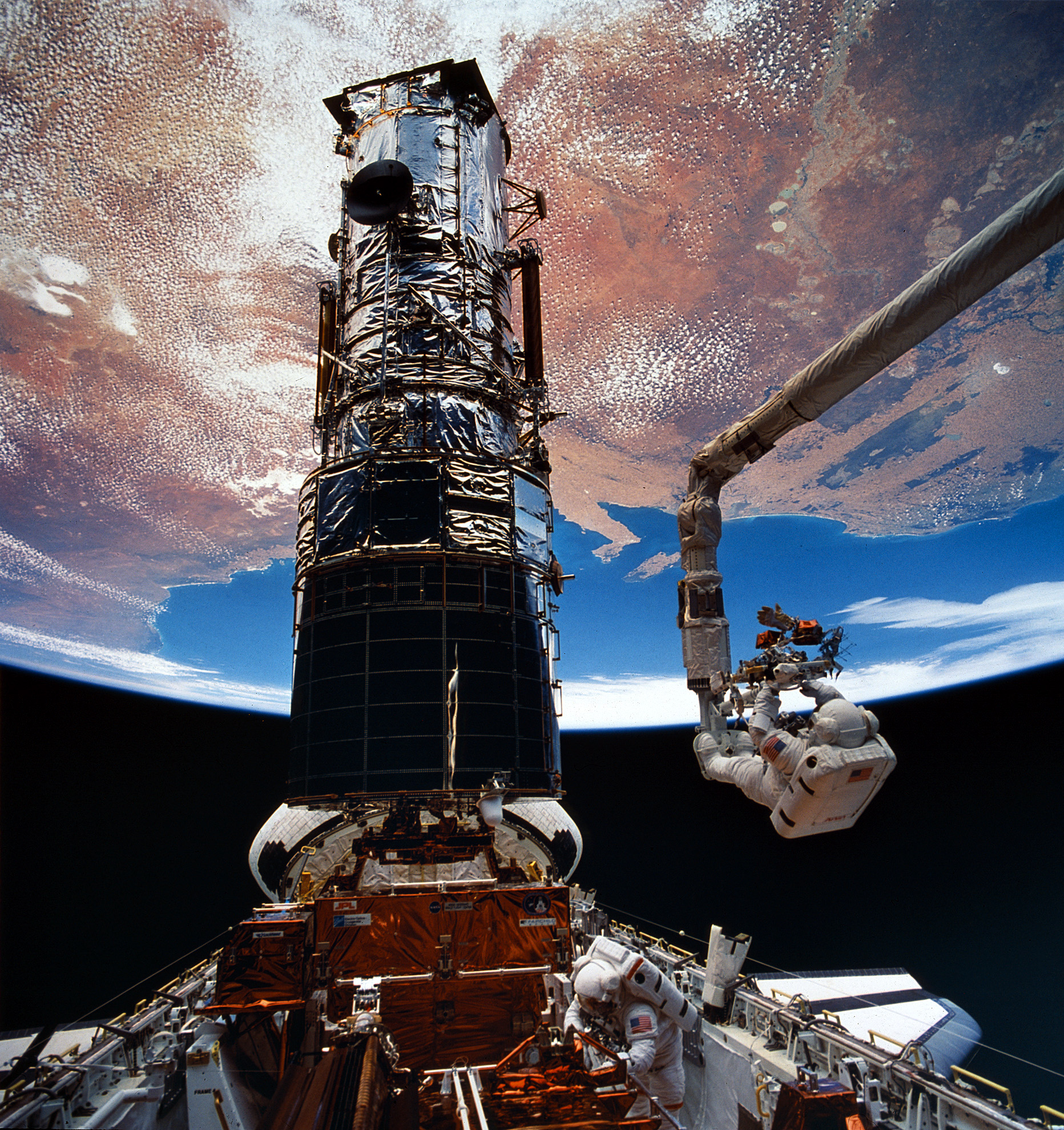

Among her accolades were the first Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing call, the first International Space Station (ISS) assembly mission and the first (and so far only) three-person spacewalk. Endeavour carried the first married couple into space and the first active-duty female military officer, as well as representatives from Japan, Switzerland, Canada, Russia, Germany, Italy and France. And she logged the third-longest mission in the shuttle’s 30-year history.

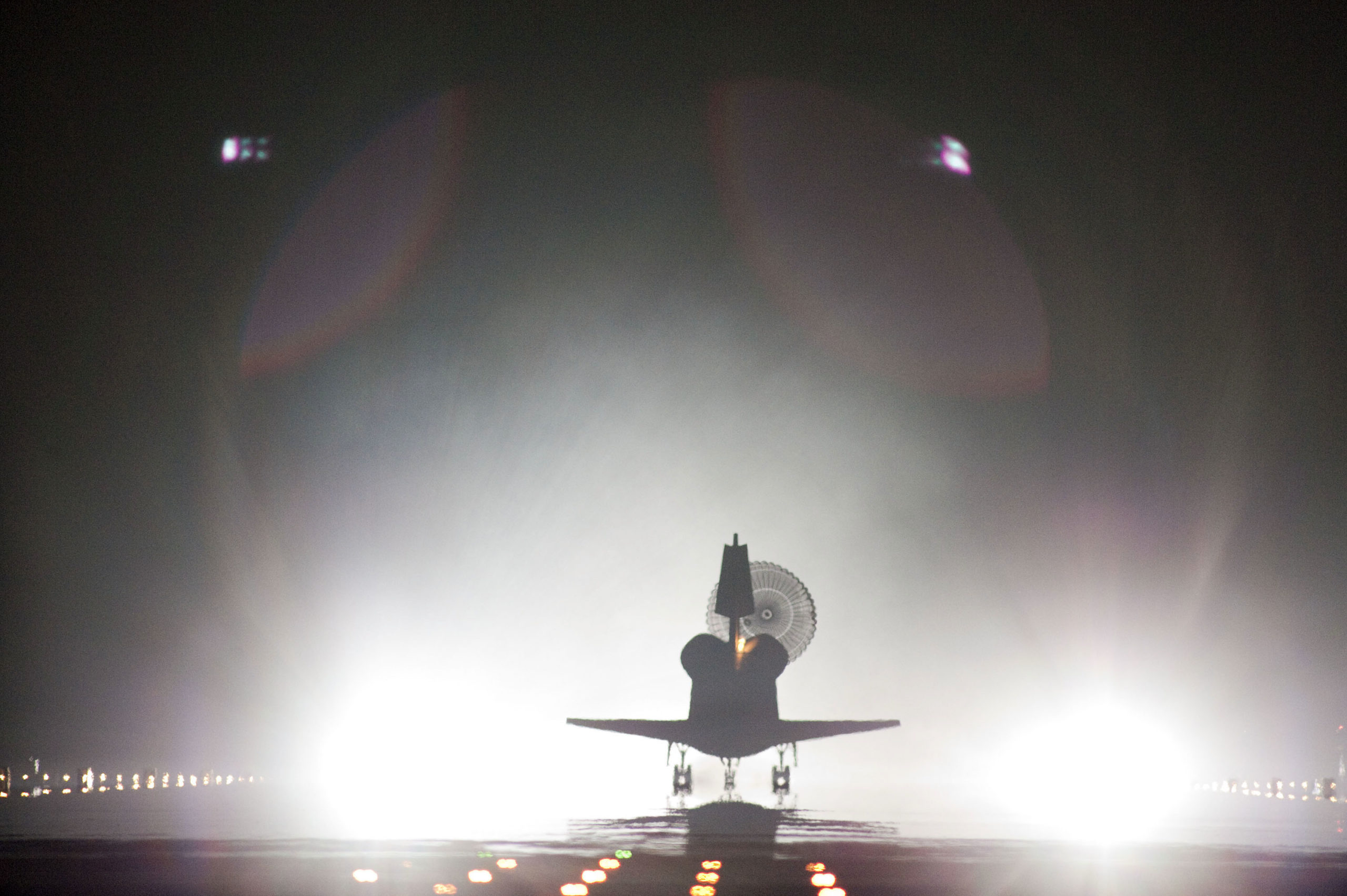

Endeavour’s final destination for permanent display at the CSC was announced by NASA in April 2011, only weeks before she flew her final space mission, STS-134. Following that historic homecoming on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) concrete runway at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, Endeavour was transported firstly to the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) for post-flight servicing and decommissioning, then flown atop the Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) to Los Angeles International Airport in September 2012. And the following month, watched by cheering spectators, she was towed through the Los Angeles streets, headed for her retirement home in Exposition Park and the CBC.

“Over one million people packed sidewalks, rooftops and even climbed billboards,” wrote AmericaSpace’s Mike Killian, who was there to see it, “to witness what was arguably the most historic move of any object through any city, ever.”

The Endeavour “exhibit” was opened to the public at the end of October 2012, in the temporary Samuel Oschin Pavilion, named in honor of the Detroit-born Los Angeles entrepreneur and philanthropist. However, the 188,000-square-foot (17,500-square-meter) Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center will form Endeavour’s permanent home in the next few years, as part of the CSC’s Phase III expansion initiative.

In addition to Endeavour herself, it was long intended to pair her up with a “real” External Tank, which proved somewhat problematic as these bulbous orange tanks were destroyed in the upper atmosphere after each flight. However, ET-94—an unflown Lightweight Tank (LWT) and the last flight-qualified shuttle external tank in existence—was donated NASA.

In May 2016, it was transported by barge from the space agency’s Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans, La., across the Panama Canal and onward to Los Angeles, then via flatbed truck from Marina del Rey to the CSC. Since construction of the Super-Lightweight Tank (SLWT) had already begun, ET-94 was considered a “deferred-build” tank and never flew an actual shuttle mission. But it was utilized extensively after the February 2003 loss of Columbia and played a fundamental role in understanding the root cause of the tragedy.

With Endeavour and ET-94 in place, completing the exhibit required a pair of four-segment SRBs. Not only was this for the aesthetic purpose of recreating an authentic shuttle “stack”, but for structural and seismic safety as it stands upright at the CSC. Dennis Jenkins, project director of the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center, made the request to Northrop Grumman. All told, the eight booster-case “segments” have previously participated in 32 ground tests and no less than 81 actual shuttle launches.

“As for the non-motor parts of the booster, we sourced a set of flight-worthy aft skirts and frustrums and a set of forward skirts that were used for tests for NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) Program in Utah and Northrop Grumman,” said Mr. Jenkins. “Northrop Grumman and NASA are providing most of the smaller parts, like booster separation motors, from surplus.”

All told, the eight segments represent an impressive cross-section of the 30-year shuttle program. Parts of the boosters were flown on the maiden missions of orbiters Challenger, Atlantis and Endeavour. The oldest-flown parts rode towards orbit on STS-5, the first “operational” shuttle mission, way back in November 1982, whilst others most recently saw in-flight service on Discovery’s last flight, STS-133 in February 2011.

And several parts flew on no less than 15 missions by Endeavour herself, including her inaugural orbital voyage, STS-49, and her second-to-last flight, STS-130. Poignantly, the boosters also include an aft dome, aft stiffener and aft External Tank (ET) attach ring which helped power Columbia’s final ascent on 16 January 2003.

“The contributions made by the Space Shuttle Program to space science and exploration have been powerful,” said former shuttle commander Charlie Precourt, who now serves as vice president for propulsion systems at Northrop Grumman. “We are excited to share a piece of our more than 30-year legacy with future generations to help inspire a new era of explorers.”

AmericaSpace would like to thank Northrop Grumman Corp.’s Kay Anderson for her assistance in the preparation of this story.