A quarter-century ago today, the Space Shuttle began living up to its billing as a machine to deliver payloads and people to an Earth-circling space station. In the wee hours of 12 January 1997, Atlantis roared into the darkened skies of the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida to kick off a ten-day mission which would exchange long-duration crew members on Russia’s Mir space station and deliver upwards of 6,100 pounds (2,800 kilograms) of cargo and supplies.

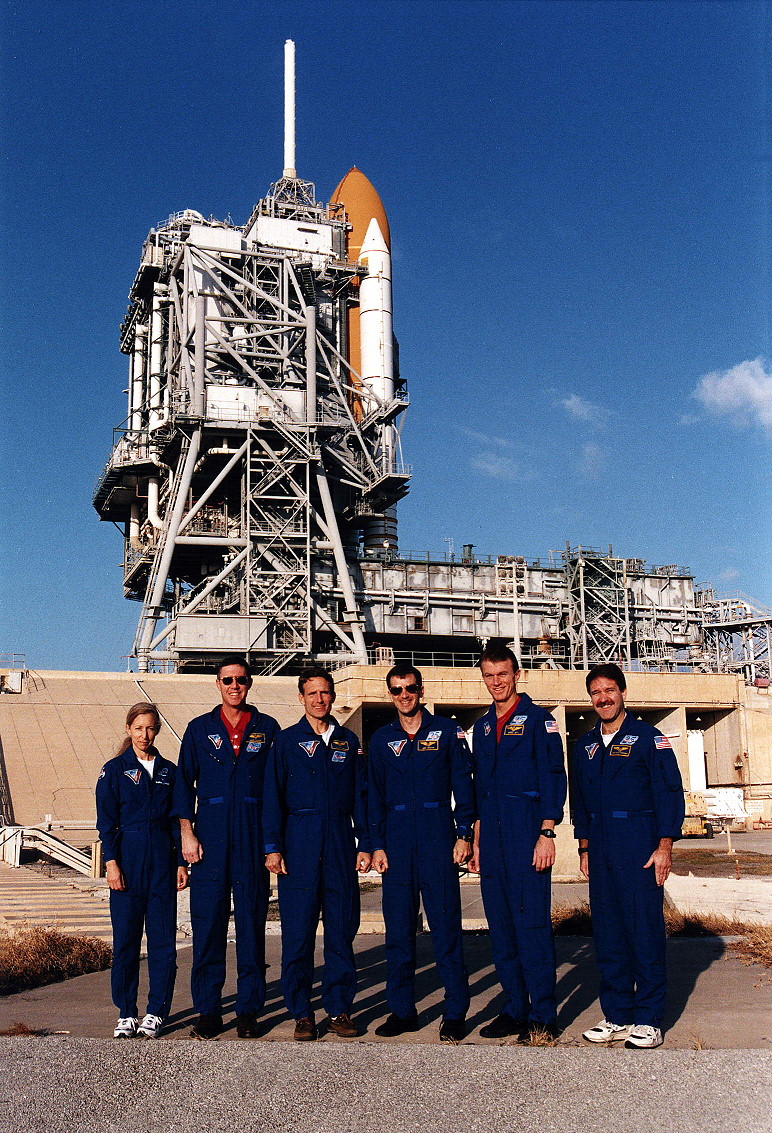

During STS-81, astronaut Jerry Linenger would be dropped off at Mir for a four-month increment, whilst John Blaha would return to Earth after his own long-term stay. In the meantime, Atlantis “core” crew of Commander Mike Baker, Pilot Brent Jett and Mission Specialists Jeff Wisoff, John Grunsfeld and Marsha Ivins, together with Mir’s own resident crew of Valeri Korzun and Aleksandr Kaleri, would support one of the the most ambitious joint flights ever attempted.

In fact, Blaha spent a considerable period since the previous Christmas readying for his departure, by packing bags with equipment to bring back home. An additional illustration of the co-operative spirit of STS-81 came a couple of days before Atlantis’ launch, when one of two cooling fans in a science freezer failed. For his part, Blaha managed to remove the door and fit a temporary replacement, to keep temperatures as cool as possible for the biological specimens inside. Replacement fans were delivered to KSC and loaded aboard the shuttle as Atlantis sat poised on the launch pad.

Among the items to be brought home by the STS-81 crew were wheat samples from Mir’s Svet greenhouse, marking the first time that plants completed a full growth cycle in space, whilst Atlantis would also deliver the Treadmill Vibration and Stabilization System (TVIS) for evaluation, ahead of a future role on the International Space Station (ISS).

In his memoir Off the Planet, Linenger reflected upon the wry sense of humor of his crewmate John Grunsfeld. As an undergraduate, Grunsfeld had worked on his car in a self-help garage run by two Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) graduates, who later started a popular radio program, Car Talk. Prior to STS-81, Grunsfeld arranged with the producers to play a prank on the show’s hosts. Whilst in space, his telephone call was patched through to Car Talk.

Without identifying himself, Grunsfeld complained about his government-issued vehicle, whose horrendous gas mileage caused a habit of running extremely roughly for the first two minutes of operation, with lots of shaking. However, after those two minutes, it performed like a champ, until the eight-minute point, when its engine died completely. The hosts were mystified. Did the vehicle attain good acceleration, they wondered?

“Oh, yeah,” replied Grunsfeld. “About 17,500 miles per hour.”

The hosts realized they had been had. “Who is this?”

Only then did Grunsfeld identify himself as a crewman aboard shuttle Atlantis.

Although both Linenger and Blaha had been training for their respective Mir increments for more than a year, the STS-81 core crew was announced in February 1996. Launch was targeted for December, but a series of Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) troubles the following summer pushed it back to January 1997.

During training, Jett took time to design the crew patch, which was V-shaped to honor the Roman numeral for five, illustrative of STS-81’s status as the fifth shuttle-Mir docking flight. With Baker and Jett in charge of the rendezvous and docking, Wisoff oversaw the Orbiter Docking System (ODS) and the Spacehab cargo module, Grunsfeld was the mission’s flight engineer and computer network expert, whilst Ivins served as “loadmaster”, with responsibility for cargo transfer operations.

In May 1996, the crew spent two weeks in Russia for training with the cosmonauts. “I probably never thought I would get a chance to go over to Russia,” Jett recalled, “at least back in the days when I was actively flying in the military.”

Arriving in Moscow during the Victory Day celebrations, Jett was struck by their intensity, as Russians reflected on their triumph over Nazi Germany. One night, as the STS-81 astronauts stood on a bridge over the Moscow River, gazing at the Kremlin necropolis, they expressed quiet astonishment. “The streets were closed down,” said Jett. “People were standing in the streets and watching fireworks all over the city and there were probably seven or eight different locations where fireworks were going off. The Kremlin was all lit up.”

All told, Atlantis’ processing flow progressed smoothly, punctuated only by the need to replace a fuel cell in mid-November, which had exhibited high pH levels. The STS-81 crew and Linenger arrived at KSC on 8 January, ahead of the formal start of the 43-hour countdown. They were awakened 11 hours before launch, but rested through the day and proceeded to the suit-up room at midnight. Clad in their bulky suits, they boarded the Astrovan for the journey to Pad 39B.

Liftoff occurred at 4:27:23 a.m. EST, right at the opening of the ten-minute “window,” at which time Mir was high over the Galapagos Islands. Although it was Baker’s first launch in the hours of darkness, Jett had done this before. Two things sprang to mind: the extreme brightness out the window and the sure knowledge that he was leaving Planet Earth. Atlantis’ computer-commanded “roll program” maneuver, ten seconds after liftoff, was particularly noticeable. “From the pilot’s seat, you really feel the roll program a lot more than you perceive it visually,” Jett said later.

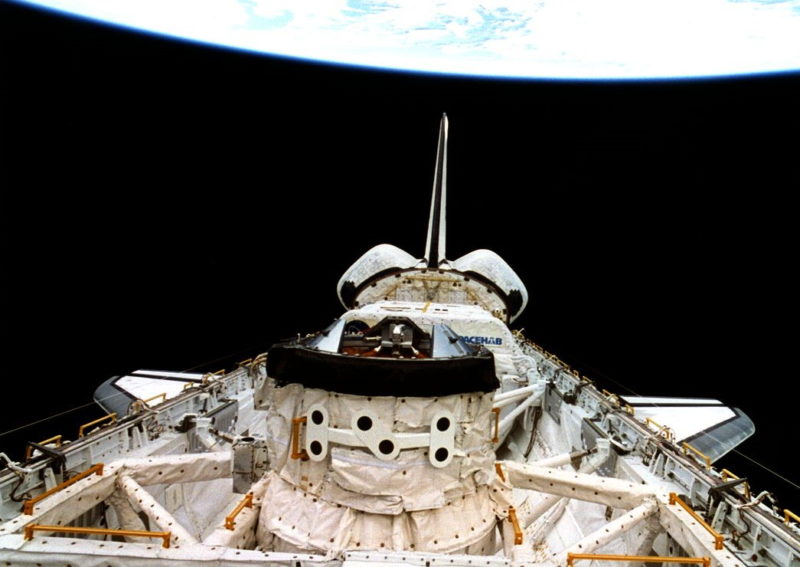

About 25 minutes after liftoff, the Mir crew was notified that Atlantis had reached achieved orbit and watched a video uplink from Mission Control. The two-day flight to reach the station was a busy time, as the STS-81 astronauts set up laptop computers and laser range-finding gear and activated the Spacehab module. Wisoff, Grunsfeld and Linenger set up and tested TVIS, Ivins activated Europe’s Biorack facility and the crew worked together to set up the centreline camera in the ODS for docking.

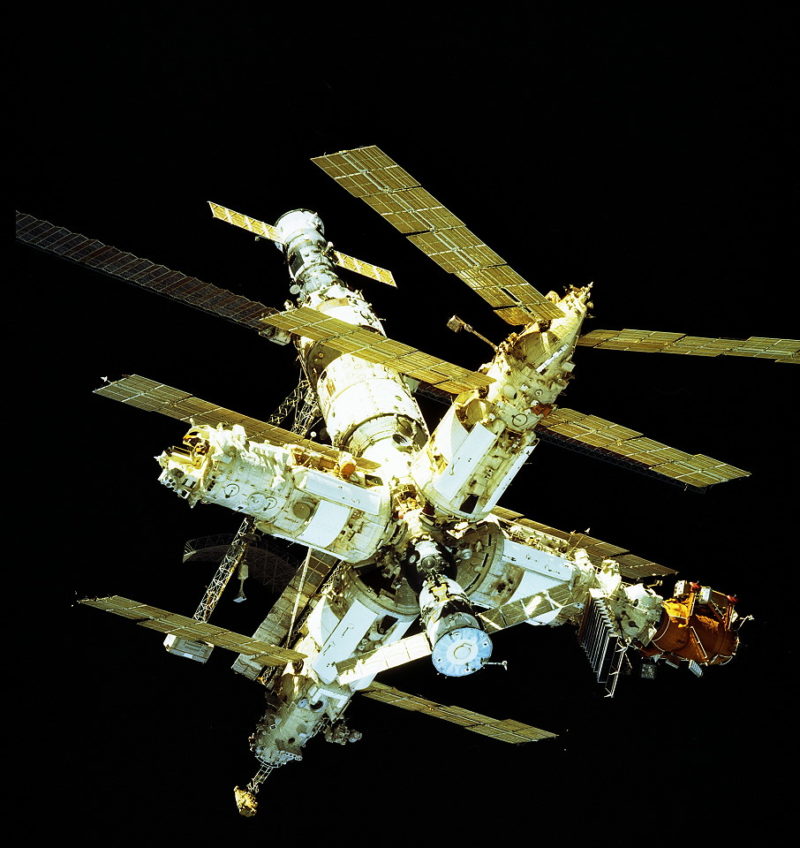

“Good morning, Houston, 500 miles to go,” radioed Baker cheerily early on 14 January, as the shuttle closed in on Mir. The approach followed an imaginary “line”, extending from Earth’s center towards the station, and was known as the “R-Bar”. Its use enabled Baker and Jett to exploit natural gravitational forces to assist with braking and limited the requisite number of thruster “burns”.

They spotted Mir from a distance of 40 miles (64 kilometers), but from the station itself Blaha could not see them until a few minutes before docking. Flying Atlantis from the aft flight deck controls, Baker assumed manual control at a distance of around a half-mile (800 meters) and used the ODS centerline camera to guide him to his target: the orange-colored Docking Module (DM) at the end of Mir’s Kristall module. At 30 feet (9 meters), he reached a station-keeping hold-point, after which a final “Go/No-Go” from the control centers in Houston and Moscow authorized him to press ahead with the final approach.

The closing phase of the rendezvous occurred at just 0.1 feet (3 centimeters) per second, producing a perfect docking at 10:55 p.m. EST on 14 January. Ivins clapped Baker on the back in congratulation. “Nice job, Bakes”, someone said.

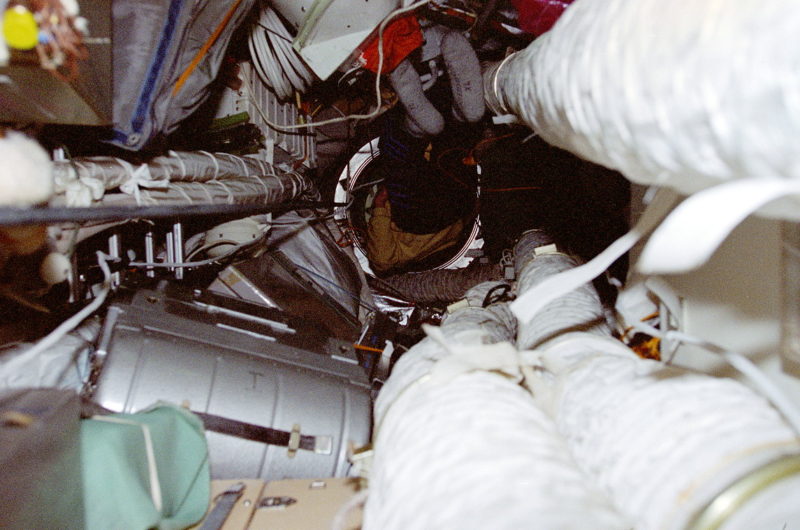

Shortly afterwards, Linenger—wearing his Stars and Stripes socks—worked to equalize pressures between Atlantis and Mir, ahead of hatch opening. Banging on the other side of the hatch, a chorus of “open it up” was emitted by Korzun, Kaleri and Blaha. And when those hatches were finally opened, Blaha let out an uninhibited laugh.

“Then bedlam erupted,” Linenger wrote, “as the six of us blundered our way through the hatch and bumped heads with the much more graceful (being fully adapted to space) threesome of Mir occupants. The scene was one of hugs, shouts, mixed language and laughter, feet dangling in all directions. Nine spacefarers embracing and floating in every which way. After the chaos calmed, we all migrated, single file, heads closely following feet, into Mir.” The sheer pandemonium was enjoyed by Mission Control in Houston. “Atlantis, Houston,” radioed the Capcom, “if you keep keying that mike, we love the sound!”

Over the next five days, the two crews—nine humans in total—transferred over 6,100 pounds (2,800 kilograms) of cargo and supplies to Mir. This included essentials like new flashlights for Korzun and Kaleri, since large sections of the station were being kept dark to conserve power. Each evening, Blaha spent a few hours with Linenger, discussing technical aspects and mundane, everyday tasks.

“We went through how the toilet works, how the treadmill works and he did his routine,” Linenger wrote. “He explained in detail how he cleaned himself after working out on the treadmill; there’s a trick to it. Water is in short supply up there and you need to use two or three thimblefuls, which you put on a little towel. He would cut the towel into about five or six sections to conserve towels, because there’s no way to keep delivering new towels. He showed how you can make a couple of thimblefuls of water go a long way. Sanitation was not an easy task up there. During your treadmill sessions, you would definitely be sweating and our T-shirts would get soaked. Our supply of shirts and shorts was such that we could only change every two weeks.”

As Blaha provided his “unalloyed frankness” and “uncensored remarks” to Linenger, the rest of the crew busied themselves with transferring cargo to and from the Spacehab module to Mir and back. In charge of the transfer, Marsha Ivins “ruled with an iron fist”, according to Linenger. “She demanded that every item be in its proper place.”

Living for a few days aboard Mir, Grunsfeld likened the station to “exploring a cave”, whilst Linenger added a similarity to an old, musty wine cellar, with a warren of cluttered passageways. At times, the nine astronauts and cosmonauts gathered for joint meals.

“It’s customary when the shuttle docks that the crews have a big meal together,” remembered Wisoff. “And when our STS-81 crew arrived, the cosmonauts had recently had a supply ship come up. They had a big round ball of cheese and they had a fresh salami, or summer sausage. They had an axe and they were chopping this thing up and tossing out pieces to us. It was like being in a space deli.”

Hatches between Atlantis and Mir were closed early on 19 January. Following depressurization and a good night’s sleep, the shuttle undocked at 9:15 p.m. EST. Baker pulsed the thrusters to maneuver to a safe distance, after which Jett took control for a customary flyaround inspection of the station.

Landing on the 22nd was waved off for one orbit, due to forecasted and observed cloud cover at KSC, before Baker was finally given the go-ahead to initiate the irreversible deorbit “burn”. Descending over British Columbia, near Vancouver, then across Nebraska and the United States’ central heartland, the shuttle finally entered Florida airspace and touched down on Runway 33 at KSC at 9:23 a.m. EST.

Having been in space since the previous September, Blaha logged 128 days in space, making him the most flight-experienced U.S. astronaut at that time, surpassing Norm Thagard. A seasoned shuttle commander, Blaha had discussed flying the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA), right after landing, to evaluate his ability to land the spacecraft after a long stay in space. Before the flight, he assured Dave Leestma, the head of flight crew operations, that he could do it, but after landing the reality hit him. When Blaha disembarked from Atlantis, Leestma walked up to him.

“John, are you ready to do that?”

“Dave, the answer is no,” Blaha replied sadly. “And even if I mentally wanted to, I physically could not do it.” In a NASA oral history, Blaha noted that he felt fine in orbit and during landing and rollout, but after a while the cardiovascular and vestibular issues associated with a long stay in space took their toll. “After wheelstop, it was like all the connections came undone,” Blaha remembered, “which was a real shocker to me, since I had never had any symptoms.”

It was a disappointment, for Blaha knew that future visitors to Mars would need to land their spacecraft after a long period of weightlessness. On the barren, inhospitable surface of the Red Planet, there would be no-one to help them. “I don’t see a therapist there to work with you,” he said. “I don’t see a flight surgeon waiting for you to land on Mars. I don’t see a swimming pool for you to work out in for a month.” It was another stark reminder that many problems of long-duration spaceflight needed to be resolved before humans could take their next steps into the cosmos.