SpaceX’s third ten-times-flown Falcon 9 roared aloft Thursday from storied Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., to support the multi-payload Transporter-3 mission. Liftoff of the B1058 core stage—which first saw service to lift NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to orbit aboard Dragon Endeavour for the historic Demo-2 flight to the International Space Station (ISS) in May 2020—took place at 10:25 a.m. EST.

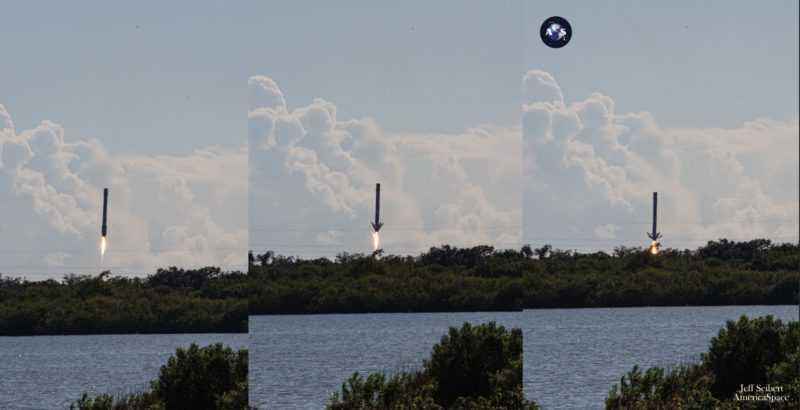

Around eight minutes later, B1058 completed its tenth on-point touchdown (and its first on solid ground) when it alighted smoothly at Landing Zone (LZ)-1. Meanwhile, over the course of the next 1.5 hours, a total of 105 Transporter-3 “rideshare” payloads spanning a multitude of scientific, educational and technical disciplines and representing the efforts of over 20 sovereign nations were deployed into orbit.

As its name implies, today’s launch was the third dedicated SpaceX Transporter rideshare, following hard on the heels of Transporter-1—which also flew atop the B1058 core in January 2021—and Transporter-2, last summer. Of note, Transporter-1 retains a record for the greatest number of discrete payloads ever launched to orbit by a U.S. booster.

Photo Credit: Jeff Seibert/AmericaSpace

All told, 143 small satellites totaling around 11,000 pounds (5,000 kilograms) were emplaced into Sun-synchronous orbit. They included ten of SpaceX’s homegrown Starlink internet communications satellites and 133 CubeSats, microsats and Orbital Transfer Vehicles (OTVs) from a multitude of commercial and U.S. Government entities.

Among the Transporter-1 haul, which marked SpaceX’s inaugural SmallSat Rideshare Program Mission, were several Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) instruments for Earth observations, together with miniaturized satellites devoted to weather and climate monitoring, the measurement of aerosol pollutants and other “greenhouse gases” and student-led investigations into terrestrial, ionospheric and solar physics.

Multiple technology demonstrators also rode Transporter-1, ranging from optical communications systems to autononomous formation-flying satellites and from rendezvous and proximity operations to assessing the effects of atomic oxygen exposure upon spacecraft components. And the contributions to Transporter-1 were truly international in their depth and breadth, spanning students and research teams from the United States to Germany, from Finland to Canada, from Italy to Taiwan and from Switzerland to Japan.

The 88-strong Transporter-2 haul, which flew in June of last year, proved an equally complex and impressive endeavor. Although it carried numerically fewer payloads, SpaceX noted that this second mission actually featured “more customer mass” than its predecessor. All told, it featured 20 nations—from Argentina to the United Kingdom, from Finland to the United Arab Emirates and from the Netherlands to Thailand—and included Kuwait’s first CubeSat, devoted to student satellite communications technology.

Like Transporter-1, the payloads covered a smorgasbord of disciplines from X-band SAR to real-time streaming of Earth, from optical and hyperspectral imaging to meteorology and from maritime observations to laser communications and amateur radio.

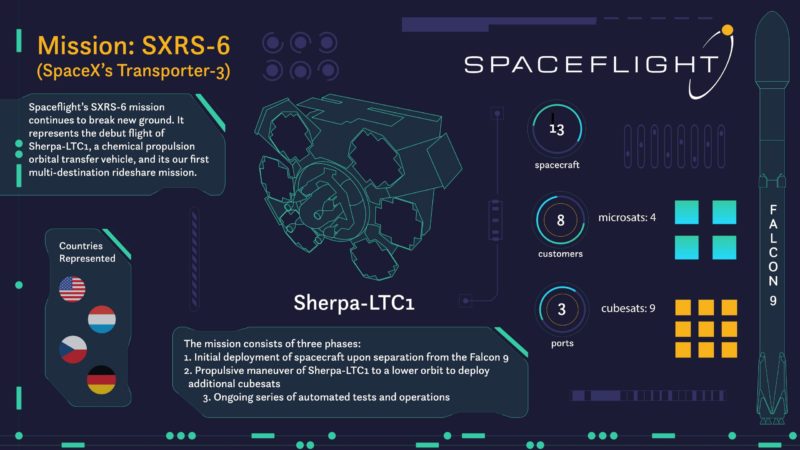

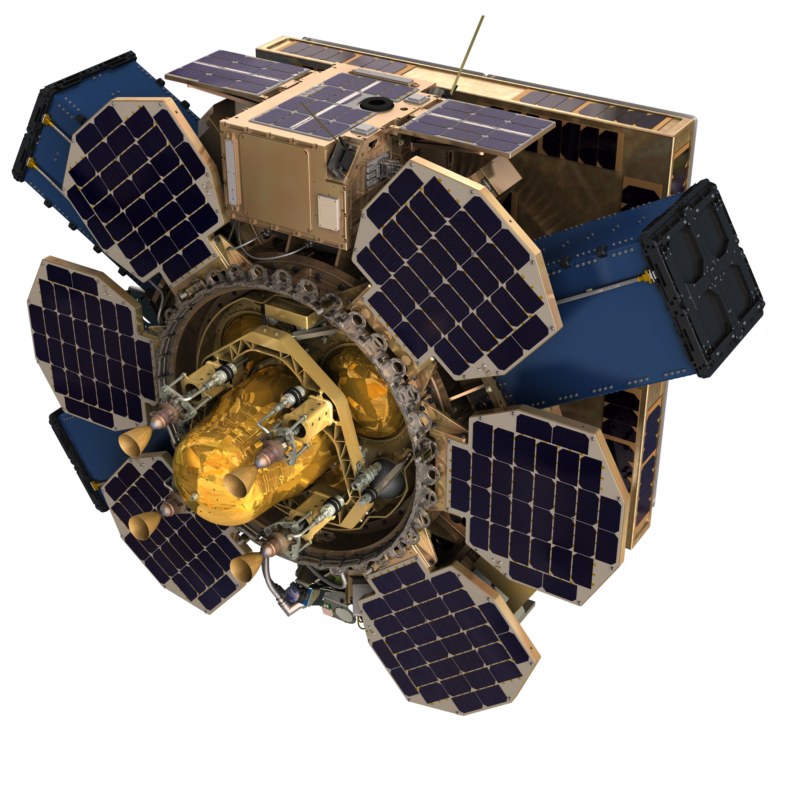

But these two initial flights were just the beginning. In June 2020, Seattle, Wash.-headquartered smallsat provider Spaceflight, Inc., signed a deal with SpaceX to secure capacity on “several” Falcon 9 flights. Last November, Spaceflight announced its intent to fly 13 customer payloads—four microsats and nine CubeSats—aboard Transporter-3, a mission which the company internally designates “SpaceX Rideshare-6” (SXRS-6).

It was noted that the mission would see payloads put into two distinct orbits for the first time using Spaceflight’s new SHERPA-LTC commercial “tug”. This newest iteration of the SHERPA, which flew in two earlier configurations last year, would firstly deploy a handful of payloads at 326 miles (525 kilometers), before gradually maneuvering itself to a lower altitude of 310 miles (500 kilometers) to release the rest.

“Each of our SHERPA launches this year has incrementally brought vital learnings that have prepared us to launch SHERPA-LTC1 to execute our first in-space multi-destination mission,” remarked Ryan Olcott, Spaceflight’s SXRS-6 mission director. “This milestone mission validates our ability to provide customers with more customized launch options to achieve their mission objectives and get them to their final destination, even when there are no launches that initially meet their specific mission needs. Using our propulsive SHERPA OTVs for last-kilometer delivery is a ground-breaking capability for smallsats.”

The SHERPA-LTC1 last month wrapped up hot-fire tests of its Halcyon Avant propulsion system, developed by Benchmark Space Systems of Burlington, Vt. The firm had previously partnered with Spaceflight in an exclusive services agreement in August 2020. Last month’s tests occurred at Benchmark’s Pleasanton, Calif., facility and the non-toxic bipropellant system will afford 25-percent better fuel efficiency over state-of-the-art green monopropellants.

It includes a post-catalyst fuel-injection feature to furnish a performance hike of almost 100 percent over its predecessors. And SHERPA-LTC’s capacity to deliver payloads quickly to differing orbits has seen it labeled “Go Fast” by Spaceflight.

But sadly, circumstances on the ground had other ideas. A few days before Christmas—having already integrated the payloads—Spaceflight revealed a propulsion system leak from the vehicle and elected to omit SHERPA-LTC1 from the Transporter-3 mission. The company acknowledged that no damage had been incurred to the payloads, but described the incident as “a significant development” and expressed regret for the “inconveniences” caused.

Ten of the 13 SHERPA-LTC1 payloads were deleted, for anticipated reassignment to a later mission. Capella Space’s Capella-7 and 8 and Umbra Space’s UMBRA-2 (all three of which are dedicated to Earth observations) occupy a separate port and remained on the Transporter-3 manifest. However, all was not immediately lost for another of the original SHERPA-LTC1 passengers.

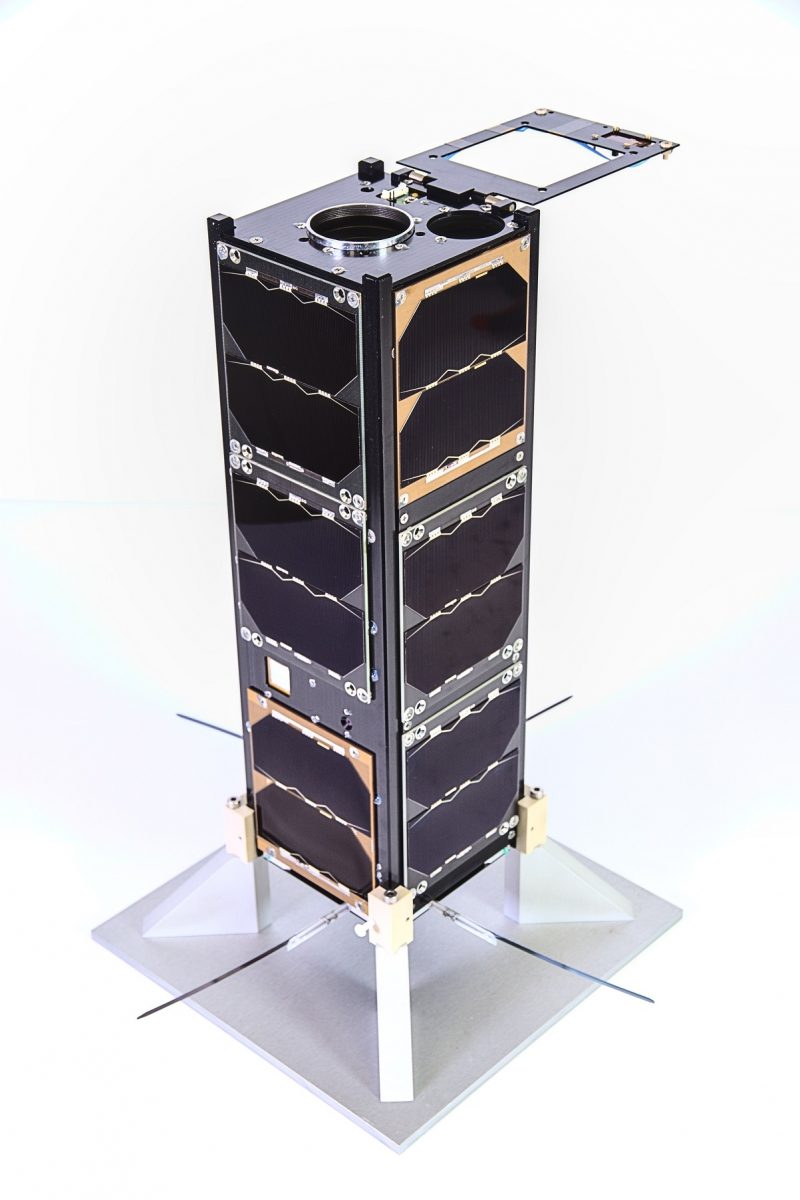

Last Monday, Spaceflight revealed that VZLUSAT-2—an Earth-imaging nanosatellite provided by the Czech Aerospace Research Center (VZLU)—had been hurriedly remanifested to fly on another of Transporter-3’s satellite dispensers, the ION Satellite Carrier, provided by the Italian firm D-Orbit. As such, it managed to keep its place on the mission.

According to D-Orbit, the last-minute integration of VZLUSAT-2 into the carrier took place on 5 January and required teams to work to an extremely tight and stringent deadline. “We are happy to have joined forces with Spaceflight to accommodate VZLUSAT on ION,” said Pietro Guerrieri, D-Orbit’s head of strategy and innovation. “This kind of accommodations truly embody the spirit of the New Space industry and, thanks to all the parties involved, everything went smoothly.”

Of the ten payloads thus “lost” from the mission, a notable pair were NASA’s Low-Latitude Ionosphere/Thermosphere Enhancements in Density (LLITED) CubeSats, tasked with investigating equatorial temperatures and wind anomalies occurring in the neutral atmosphere and the equatorial ionization anomaly which arises in regions containing charged particles. Contracts to fly LLITED were inked between NASA and Spaceflight last March and it is expected that the payload will fly an upcoming mission.

Remaining aboard Transporter-3, in addition to the Capellas, UMBRA-2 and VZLUSAT-2, were a raft of payloads reflecting the efforts of more than 20 nations. They included the first PocketQube mini-satellite fully built by Nepal, devoted to amateur radio. Others will focus upon Earth observations and technology.

Germany provided its OroraTech-1 satellite for wildfire monitoring, whilst Canada deployed four small Kepler communications satellites. Three South African-funded satellites dedicated to Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracking were accompanied by a French signals-intelligence satellite, a Dutch Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR) technology demonstrator and a British satellite whose remit includes Ultra-High-Definition (UHD) television streaming.

Tasked with lifting the 105-strong Transporter-3 haul to orbit was B1058, which becomes only the third Falcon 9 core to log as many as ten missions. And she is one of SpaceX’s true history-makers, having first seen service on 30 May 2020 when she lifted Dragon Endeavour and Demo-2 astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken on their historic voyage to the ISS. That flight saw the return of U.S. human spaceflight capability, aboard a U.S. spacecraft, atop a U.S. rocket, and from U.S. soil, since the end of the Space Shuttle Program.

Since then, and including today’s launch, B1058 went on to log an additional nine flights, lifting 295 Starlink internet communications satellites to low-Earth orbit, as well as South Korea’s ANASIS-II military satellite, the record-setting Transporter-1 and its 143 payloads and the CRS-21 Cargo Dragon to the space station.

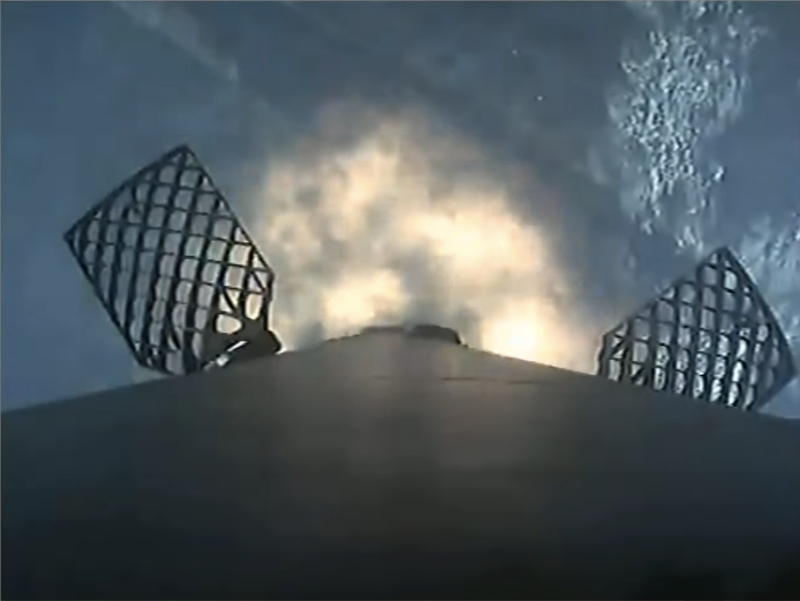

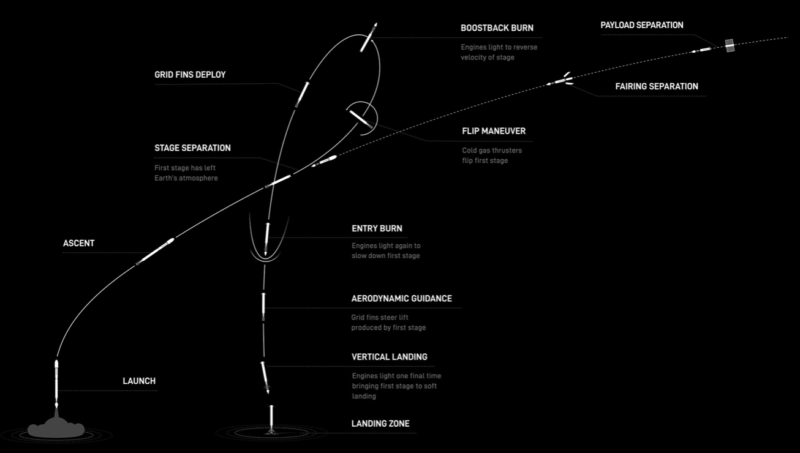

After each of her first nine launches, she returned to alight on the deck of the Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship (ASDS) in the Atlantic Ocean, but for Transporter-3 she was tasked to return to solid ground with 2022’s first landing on LZ-1 at the Cape.

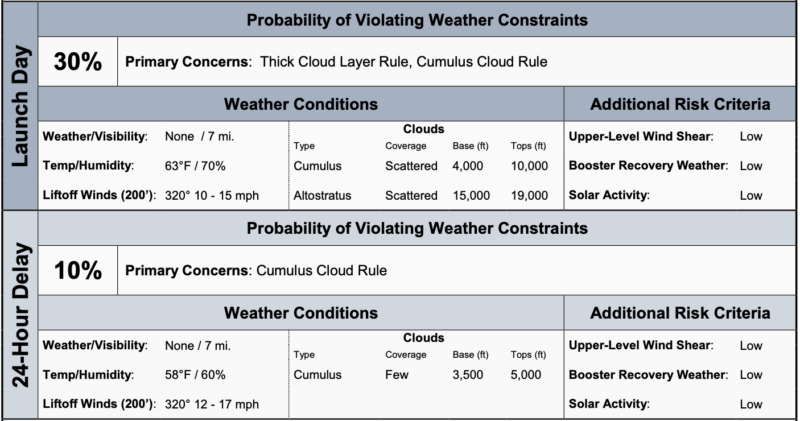

The weather prospects for Thursday morning’s launch therefore had to accommodate conditions both at liftoff and touchdown. In its Wednesday morning update, the 45th Weather Squadron at Patrick Space Force Base identified a 70-percent likelihood of acceptable conditions, improving to 90 percent by Friday.

“A high-pressure center is sliding off the coast of the southeastern U.S. this morning as a weak trough lingers offshore eastern Florida,” it noted. “The gradient between these two features will continue to bring breezy conditions to the Spaceport, along with a few passing showers.”

Although predicted cloud cover and additional showers were expected to dissipate in time for Thursday’s 29-minute launch window, concern lingered over “enhanced mid-level clouds”, with the Thick Cloud Rule and Cumulus Cloud Rule considered potential showstoppers. But as the surface low was expected to move over the Atlantic Ocean late Thursday, a brighter outlook for Friday anticipated just a handful of cumulus clouds.

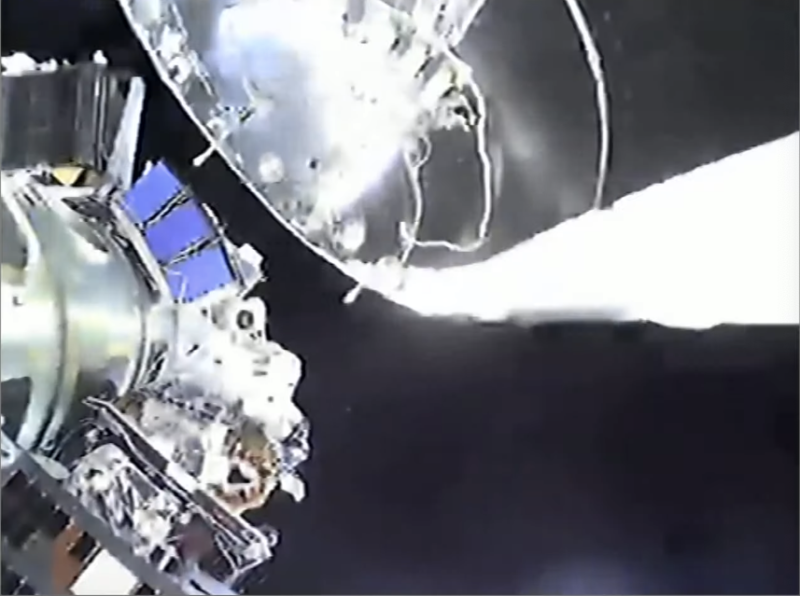

Liftoff occurred on time at 10:25 a.m. EST and B1058 powered smoothly uphill under the 1.5 million pounds (680,000 kilograms) of thrust from her nine Merlin 1D+ engines. The core stage separated from the stack at 2.5 minutes into ascent and the ten-times-flown booster alighted on LZ-1 to mark SpaceX’s first “land” landing of 2022. The most recent LZ touchdown came last June after the Transporter-2 launch.

Photo Credit: Jeff Seibert/AmericaSpace

All told, since December 2015, SpaceX has successfully landed rockets on solid ground on 24 occasions, including the simultaneous touchdowns of both side-boosters from the first three Falcon Heavy missions. Only one booster aiming for a “land” landing failed to achieve its target. Three landings occurred on LZ-4 at Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif., the others at adjacent LZ-1 or LZ-2 at the Cape.

These respective landing zones are all repurposed launch pads. In the case of LZ-1, used for today’s mission, in a past life it served as the Cape’s Launch Complex (LC)-13 and saw off 52 Atlas rockets between August 1958 and April 1978. Notable in LC-13’s history are the launches of the five Lunar Orbiter missions between August 1966 and August 1967.

With B1058 gone, the Merlin 1D+ Vacuum engine of the Falcon 9’s upper stage executed its own six-minute-long “burn” to lift Transporter-3 to orbit. Shutting down at 8.5 minutes after liftoff, the stack coasted until 59 minutes into the flight, when the half-hour deployment process got underway.

First out was Germany’s Unicorn-2E Earth observation satellite, followed over the next handful of minutes by a further 30 small payloads from the EXOport-6 interface. The remainder deployed from their respective ports in rapid succession, with the final small satellite departing at 97 minutes into the flight.

Current plans are for up to three more dedicated Transporter missions as soon as March, June and October. Manifests aboard all three remain fluid, although it anticipated that their payloads will include Tanzania’s first satellite, Kilimanjaro-1, AST SpaceMobile’s BlueWalker-3 for cellular broadband connectivity and perhaps MethaneSat to locate, quantify and track global methane emissions from oil and gas operations.

3 Comments

3 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:SpaceX Launches Next Starlink Batch, Heads Into Multi-Mission May - AmericaSpace

Pingback:SpaceX Launches Transporter-5 Rideshare , Wraps Up Multi-Mission May - AmericaSpace

Pingback:Record-Tying Falcon 9 Flies, Kicks Off Busy July - AmericaSpace