Twenty years ago, this week, the crew of Shuttle Atlantis rocketed to orbit, bound for a docking with the Mir space station. It was the third occasion—following STS-71 in June 1995 and STS-74 in November 1995—that the United States had accomplished a physical docking with Russia’s Earth-circling outpost and the fourth time that a member of NASA’s shuttle fleet had performed rendezvous with a space station. However, when Commander Kevin Chilton, Pilot Rick Searfoss, and Mission Specialists Linda Godwin, Rich Clifford, Ron Sega, and Shannon Lucid boarded Mir on 24 March 1996, their STS-76 mission differed from its predecessors in two important aspects: They would perform the first U.S. spacewalk outside a space station since the Skylab era and, for the first time, would transfer an astronaut to Mir for a long-duration stay. In so doing, Chilton’s crew was the first shuttle team in history to land with fewer astronauts than it had on launch.

Since 1992, and the first negotiations between the United States and Russia to establish the “Phase 1” shuttle-Mir program, it had always been intended that at least one American citizen would embark on a stay of several months aboard the station. Veteran shuttle astronaut Norm Thagard became the first of his countrymen to board Mir in March 1995, flying to the station aboard a Soyuz spacecraft and returning aboard STS-71. As Russia was drawn into the fledgling International Space Station (ISS) effort, up to 10 shuttle-Mir missions were manifested, including “at least four astronaut flights” of long-duration nature. In November 1994, veteran astronauts Shannon Lucid and John Blaha were named to train for the second of these long-duration flights, targeted to begin in early 1996.

A few days later, Kevin Chilton—an experienced NASA astronaut, who had previously piloted the maiden voyage of Shuttle Endeavour and later the Space Radar Laboratory (SRL)-1 mission—was named to command STS-76, which would begin this salvo of astronaut transfers. In April 1995, he was later joined by Searfoss, Godwin, Clifford, and Sega, with a targeted launch date of March 1996. At the same time, Lucid was named as the prime crew member for the long-duration flight, with Blaha serving as her backup.

By this time, Lucid and Blaha were deep into pre-flight preparations at the Star City cosmonauts’ training center, on the forested outskirts of Moscow, and were joined throughout the course of 1995 by more NASA astronauts: Jerry Linenger and Scott Parazynski were named in March, and Wendy Lawrence was named in September. However, the arrival of Parazynski and Lawrence led to one of the strangest events in the U.S./Russian partnership to date. In mid-October, NASA revealed that Parazynski—who stood 6 feet 2 inches (188 cm)—would discontinue training, “due to concerns about his ability to safely fit in a Soyuz descent vehicle for landing.” Shortly thereafter, Lawrence, too, was withdrawn from long-duration training, because her height of 5 feet 3 inches (160 cm) fell about an inch short of recently-updated Soyuz rules.

The pair quickly earned the nicknames of “Too Tall” and “Too Short” and even went on to wear self-deprecating name tags to this effect on their flight jackets. …

Against this backdrop, Lucid and Blaha trained for the second half of 1995 for what would turn out to be the longest mission ever undertaken by a U.S. citizen at that time. Unlike Thagard, Lucid—a veteran of four previous spaceflights—would not launch or land in a Soyuz, but would ride to orbit aboard Shuttle Atlantis on STS-76 in March 1996 and return to Earth aboard the same orbiter on its next mission, STS-79, in August. In doing so, she would complete a voyage of around 143 days, during which time Russia’s long-delayed Priroda (“Nature”) scientific module was expected to arrive, laden with U.S. research payloads.

In addition to performing the first astronaut delivery to Mir, STS-76 also marked the first flight of Spacehab’s logistics module. This was a modified version of the commercial research module, accommodated in the shuttle’s payload bay, which had flown on several occasions since June 1993. Spacehab’s first four missions were devoted to science, but in August 1995 the company signed a $54 million contract with NASA to adjust its operation to one of logistics and resupply for at least four shuttle-Mir flights. In tandem, Spacehab invested $15 million in the construction of a “double” module—which utilized a pair of single modules and a Structural Test Article (STA), connected by an adapter ring—to enhance the upmass and downmass capabilities. STS-76 was baselined as the only flight of the single logistics module, which STS-79, STS-81, and STS-84 expected to fly double modules.

Aboard the module for Chilton’s mission was a mix of Russian and U.S. logistics, EVA tools, scientific and technological payloads, and a series of risk mitigation experiments to be conducted in advance of the construction of the ISS. Specifically, these included a replacement gyrodyne and three new batteries for Mir, a Soyuz “seat liner” for Lucid’s use in the unlikely event of an emergency return to Earth, as well as food, water, clothing, and personal hygiene items. Spacewalking tethers and tools, together with brackets and hardware for NASA’s Mir Environmental Effects Payload (MEEP), which would be installed onto the exterior of the station’s docking module, were also aboard. Rounding out the single module’s manifest were a handful of research facilities: a double rack for the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Biorack and the Life Sciences Laboratory Equipment Refrigerator/Freezer (LSLE), as well as parts for Mir’s scientific glovebox, Canada’s Queens University Experiment in Liquid Diffusion (QUELD), and the High Temperature Liquid Phase Sintering experiment.

Commanded by Chilton—whose subsequent career would see him rise to become a four-star Air Force General, the highest military rank ever attained by a U.S. astronaut—the STS-76 crew also included Searfoss, one of few Mormon spacefarers, in the pilot’s seat. Chilton’s motto for his mission was “The Spirit of ’76,” honoring both the self-determinative patriotism of the 1776 American Revolution, as well as offering a tip of the hat to a similar nickname bestowed on the Gemini VII/VI-A rendezvous mission in December 1965.

Additionally, Chilton explained later, the spirit of STS-76 centered upon Teamwork, both by the crew and personnel on the ground. Upon his return, he noted that many people approached him with the same remarks: His crew appeared to be having great fun in space and making their highly successful mission look easy. “Those things don’t happen by accident,” Chilton told an assembled audience at the Johnson Space Center (JSC), a few weeks after landing. “They happen because of a lot of dedicated hard work that’s done by each and every person in this room.”

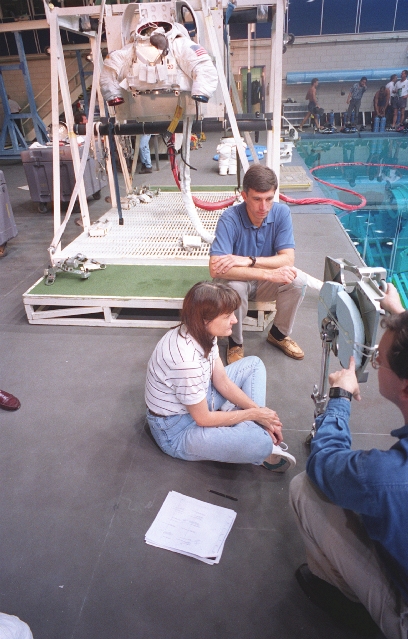

The trio of STS-76 Mission Specialists were led by Ron Sega, who had recently returned from a stint as NASA’s third director of operations at Star City, together with Linda Godwin and Rich Clifford, who were tasked with performing NASA’s first EVA outside a space station in over two decades. The core goal of the six-hour EVA was to install the four MEEP experiments onto the exterior of Mir’s docking module, which had itself been installed in November 1995 by the STS-74 crew. These experiments sought to explore the frequency, sources, sizes, and effects of human-made and natural debris as they struck Mir, capturing samples for analysis, and evaluating potential ISS materials, including paints, glass coatings, Multi-Layered Insulation (MLI), and metals. The samples were housed in four Passive Experiment Carriers, and it was intended that MEEP would remain affixed to the docking module for about 18 months, before being retrieved on STS-86 in September 1997.

Atlantis’ liftoff was planned for the small hours of 21 March 1996 from Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), but was postponed by 24 hours, due to high winds and rough seas which threatened to violate the Return to Launch Site (RTLS) abort limits. “Once the winds calmed down on the 21st,” Chilton later recalled, “the 22nd turned out to be a spectacular night to go fly.” The thorn in the side was the “ungodly hour” of launch, which occurred at 3:13:04 a.m. EDT, at the opening of a seven-minute “window.” Atlantis speared into the dark Florida sky. Despite having 12 previous shuttle missions between them, none of the crew had ever launched at night, which presented something of a surprise. After the flight, Chilton remembered the incredible brightness of the spectacle—it was like daylight, looking through his left-side commander’s window—and, following Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) separation, he also witnessed the three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) appearing to “pulsate” as they powered on toward low-Earth orbit.

A busy and complex mission lay ahead.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:‘No Reason For the People Inside to Starve’: 20 Years Since ‘The Spirit of ’76’ (Part 2) « AmericaSpace