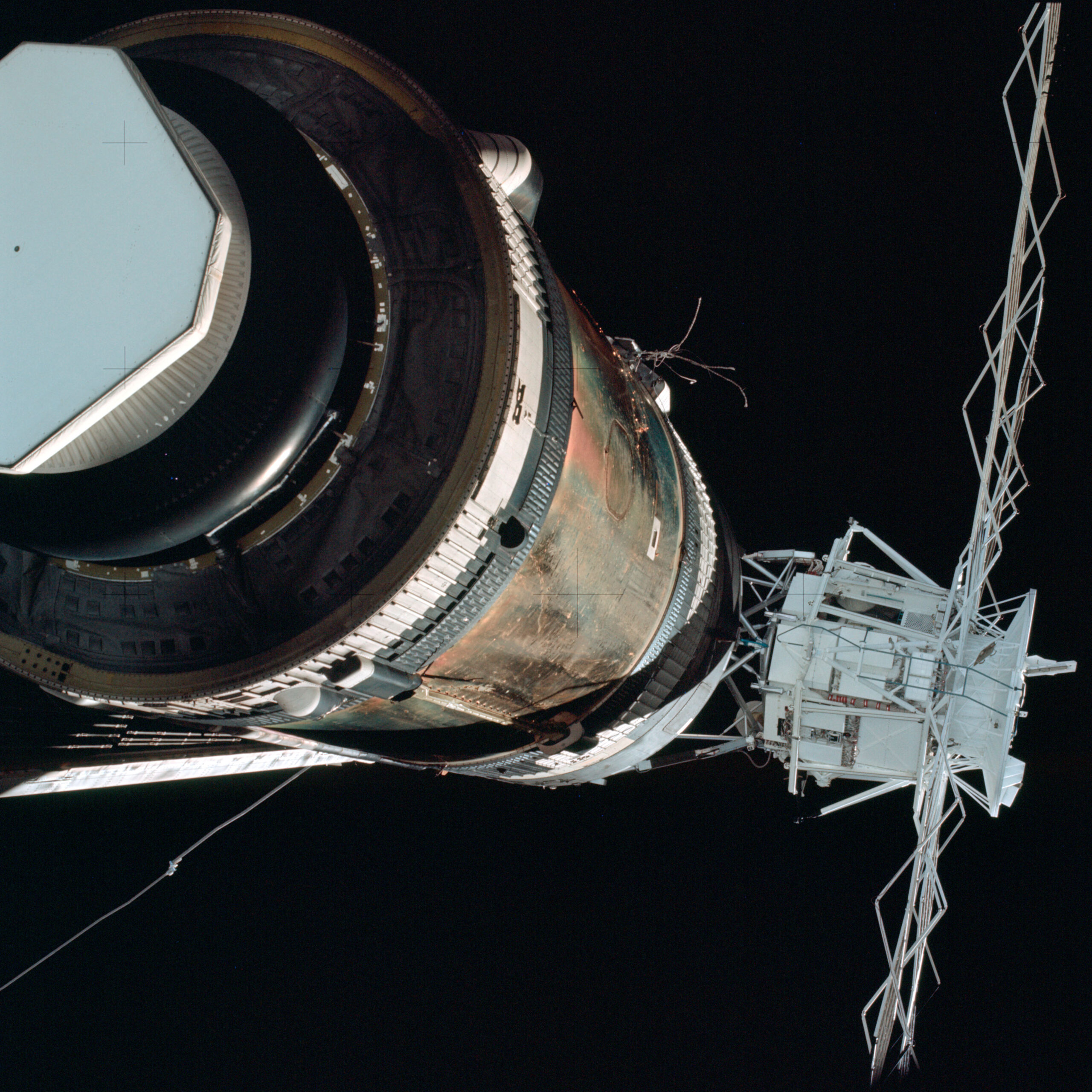

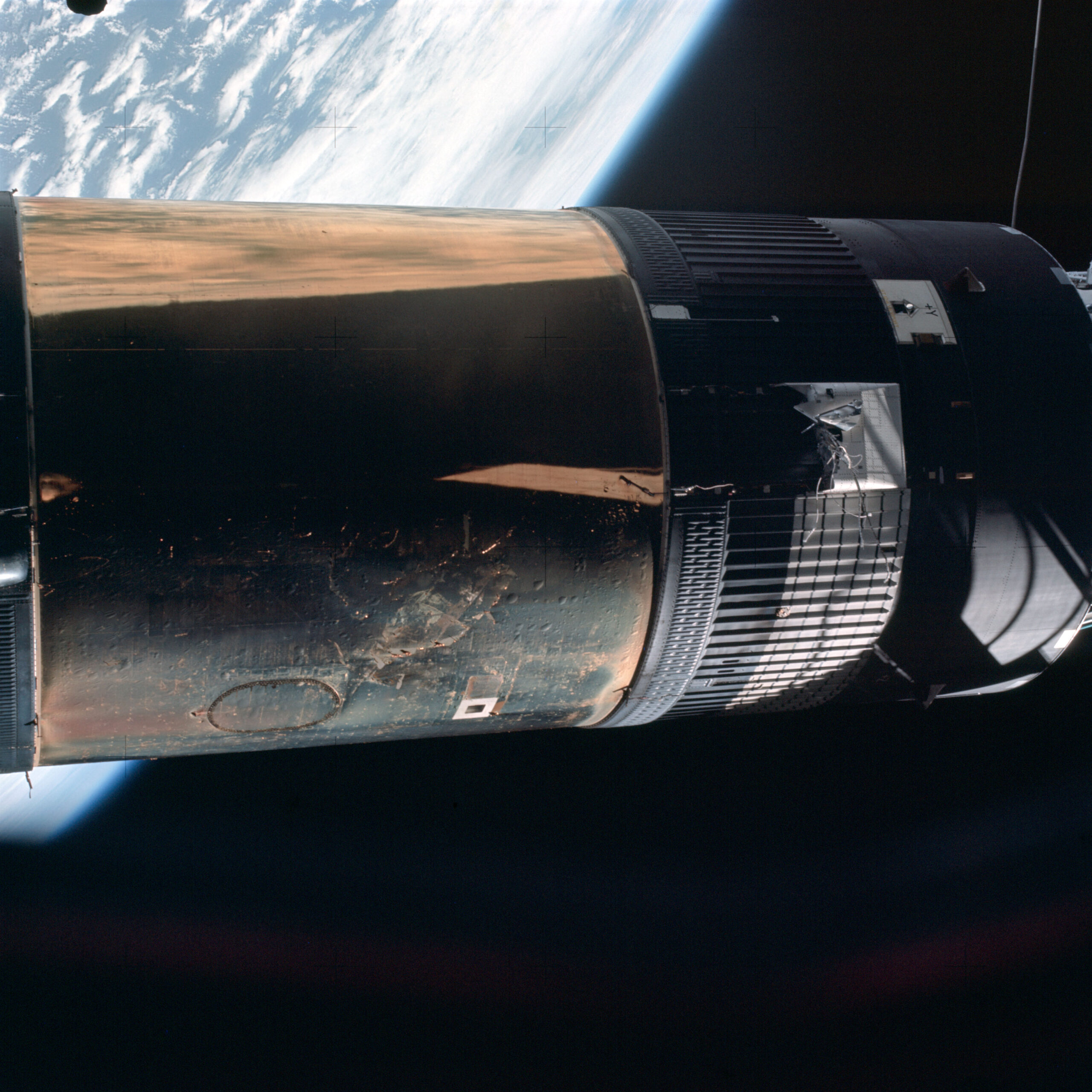

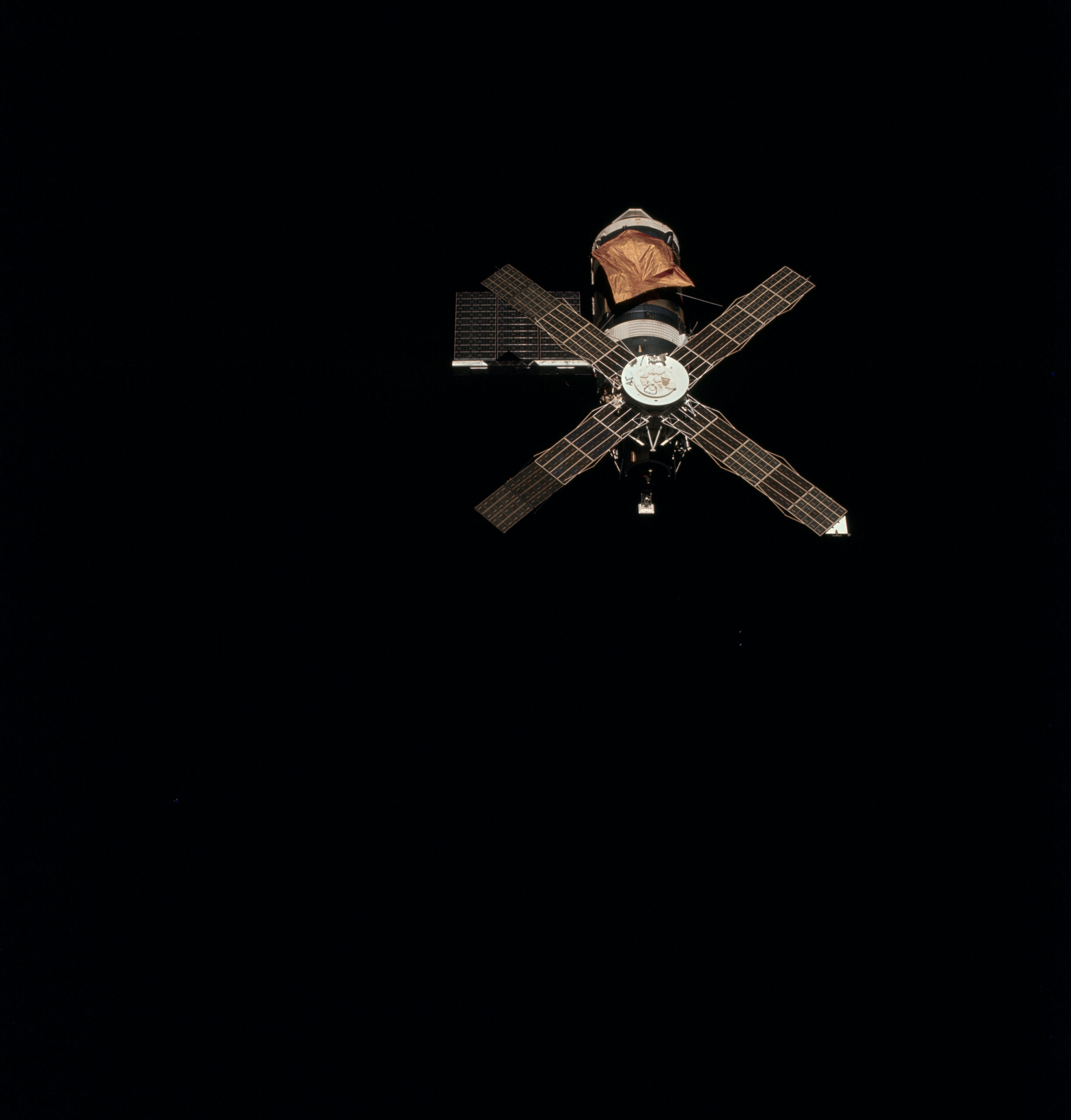

Five decades have now passed since one of the most dramatic reversals in fortune in American space history: the salvation of Skylab. On 14 May 1973, America’s first space station was launched into orbit atop the final Saturn V booster, but an unfortunate sequence of events minutes after liftoff led to the premature deployment of its protective micrometeoroid shield, which was promptly torn away in the supersonic airstream, along with one of two solar arrays.

The other solar array was left so clogged with debris that it was “pinned” to Skylab’s hull. For ten days, engineers battled to come up with a workable plan whereby Skylab’s first crew—Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Science Pilot Joe Kerwin and Pilot Paul “P.J.” Weitz—could effect a successful repair of the crippled station.

With their own launch set for 9 a.m. EDT, the morning of 25 May 1973 was peaceful for the three astronauts. “This was the least well-attended Apollo launch in history,” Kerwin recalled, “because everybody had to go home and put the kids back in school.

“We arrived at the command module and looked inside and it was a sea of brown rope under the seats,” he continued. “And under the brown ropes were all these different umbrellas and parasols and sails and also the equipment that we had selected to try and free up the solar panel, which was a pretty eclectic collection of aluminum poles that could be connected together, and a Southwestern Bell Telephone Company tree-lopper with brown ropes to open and close the jaws. Some of it we’d seen, some of it we hadn’t!”

The astronauts were unperturbed. Indeed, as their Saturn IB rocket rose from Cape Kennedy’s Pad 39B and roared into the clear morning sky, Conrad hollered at the top of his lungs that his crew could fix anything.

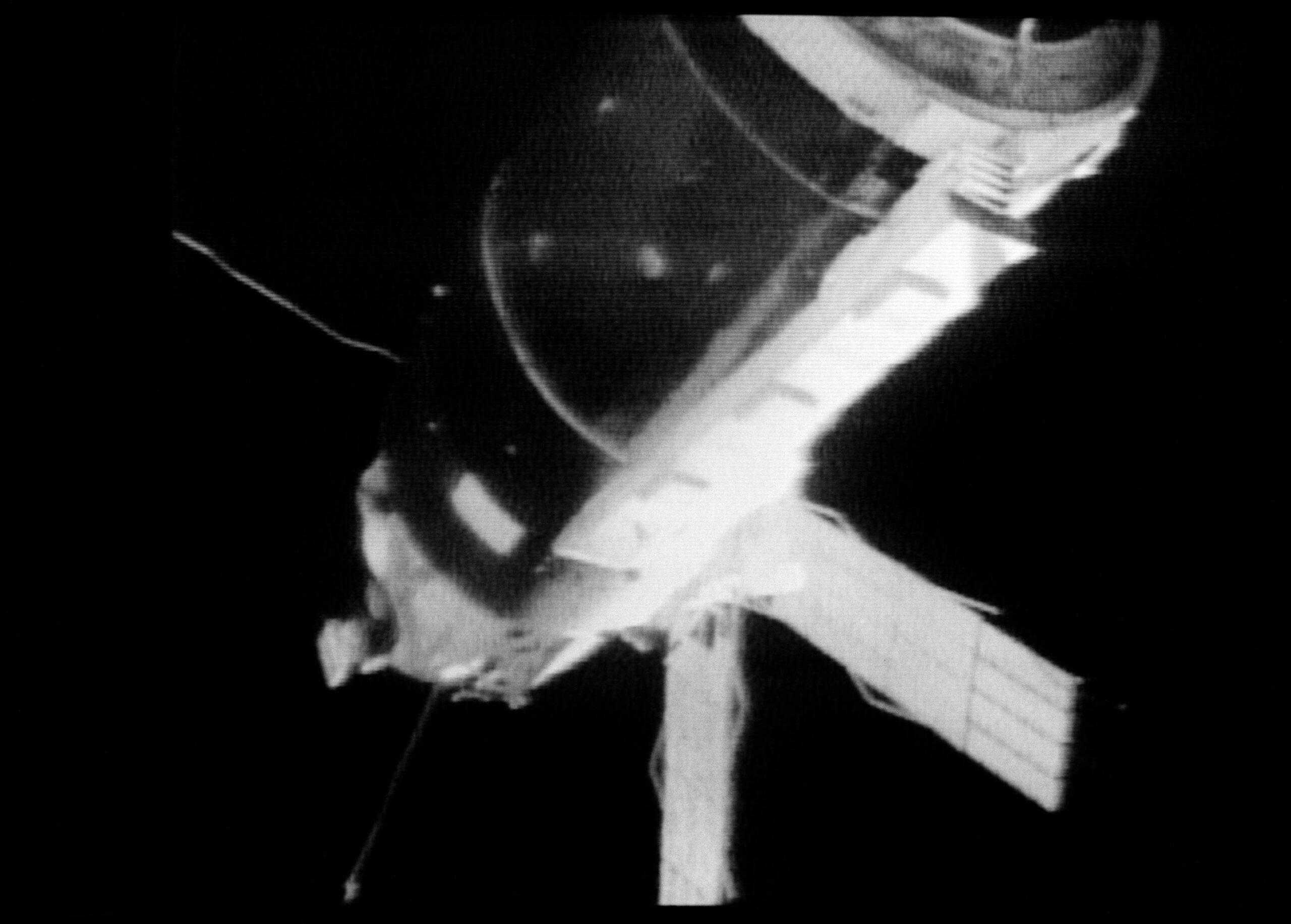

Their launch kicked off an intricate eight-hour orbital ballet to rendezvous with Skylab later that afternoon. Little did anyone know that the first day in space for Conrad and his crew would run to no less than 22 hours.

Conrad’s call of “Tally-ho the Skylab!” as a steadily brightening star on the horizon drew closer masked the seriousness of what the astronauts were about to face. The station’s micrometeoroid shield was gone, as was one of the two solar arrays, whilst the second was so jammed with debris that it could not deploy properly.

As Weitz took pictures, Conrad performed a flyaround inspection, quickly ascertaining that Skylab’s scientific airlock was not cluttered with debris, making the deployment of a special protective “parasol” for the micrometeoroid shield a realistic option, and asserting his conviction that a stand-up Extravehicular Activity (EVA), armed with a cable cutter, should be enough to free the jammed array.

The first order of business was a “soft docking” at Skylab’s forward port, engaging capture latches but not retracting the command module’s docking probe to ensure a firm metallic embrace. For a few minutes, the astronauts ate a quick dinner and prepared for the stand-up EVA.

“A full hard dock wasn’t desirable at this point, because of the likelihood that they’d undock again shortly,” wrote David Hitt, Owen Garriott and Joe Kerwin in Homesteading Space. “The docking system needed to be dismantled and reset after a hard dock.”

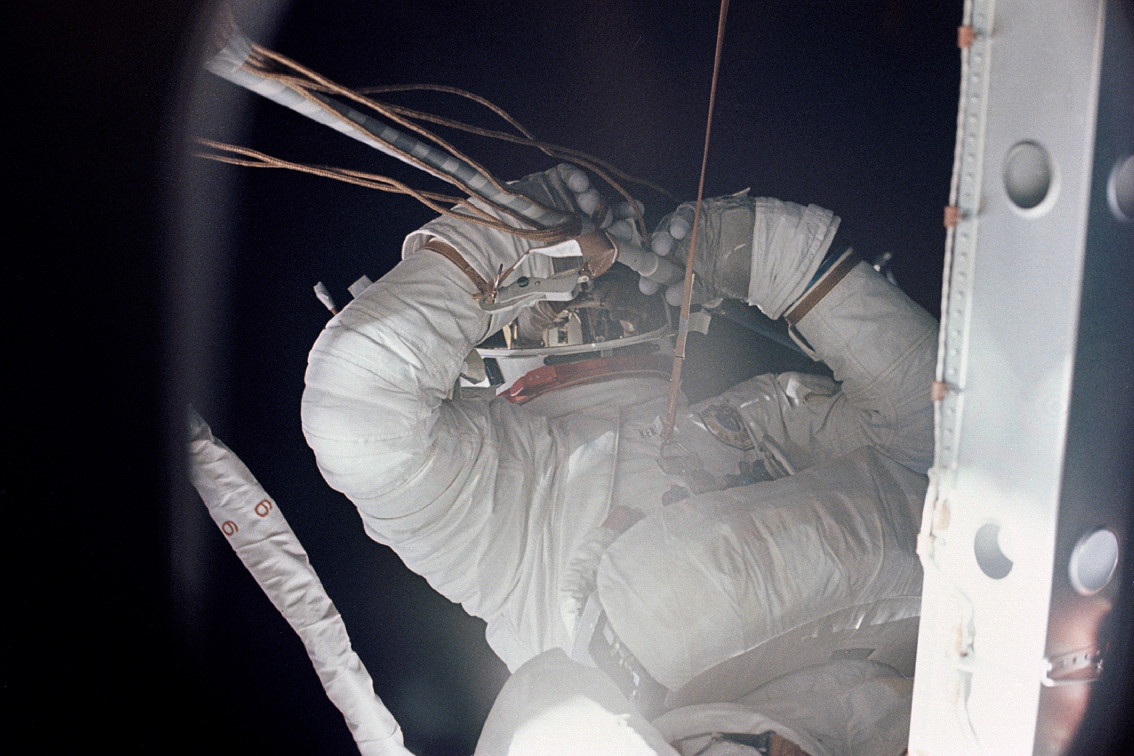

With all three men fully suited, Conrad undocked from Skylab, depressurized the cabin and opened the command module’s side hatch. With Kerwin hanging onto his ankles for stability, Weitz reached out and used modified tree loppers and a kind of “shepherd’s crook” to free the jammed array.

It should have been an occasion of euphoria for Weitz, who had not been scheduled to perform an EVA at all on this mission. But it did not go well.

At first, he positioned himself with his upper body poking through the hatch. Kerwin passed him three sections to assemble a 15-foot (4.5-meter) pole with the loppers at the end, whilst Conrad kept the spacecraft steady.

“We had seen…that there was a piece of bolted L-section from the thermal shield that had been wrapped up around the top of the solar wing and apparently the bolt-heads were driven into the aluminum skin,” Weitz recalled in his oral history. “We thought maybe we’d just break it loose, so we got down near the end of the solar array and I got a hold of it with the shepherd’s crook.”

But as Weitz heaved on it, he was pulling the command module towards Skylab. In the meantime, Conrad had the unenviable task of keeping the spacecraft close to the station and preventing the oscillations from causing a collision. The work was harder because a third of Conrad’s field of view was blocked by the command module’s open hatch.

“It made for some dicey times,” Weitz later recalled. As the two vehicles entered orbital darkness, he paused in his work, then resumed as they flew within range of the tracking station. The shepherd’s crook was getting him nowhere and the torrent of four-letter words from all three astronauts even prompted the capcom in Mission Control to ask them to modify their language; for they were on an “open mike”.

The main problem, Conrad explained, was that a strip of metal had become wrapped across the solar array during the separation of the micrometeoroid shield. Its bolts had tangled themselves in the array and none of Weitz’s actions to cut the strap, even with the loppers, were having any effect.

“Rather than cutting it across the short way, we were trying to cut along the long way,” Weitz said, “and didn’t have enough muscle with that thing, because it was six or eight feet out ahead of me and I was pulling on a line to try to do it.” The metal strap, ironically, was only a few centimetres wide, but it was riveted fast and Conrad knew they did not have a hope of breaking it using the tools in the command module.

The attempt was abandoned and the astronauts were instructed to close the hatch and re-dock with Skylab. Even this proved easier said than done: getting the pole, loppers, and shepherd’s crook back inside in a safe and speedy manner led to an inadvertent thump to Conrad’s helmet and an accidental kick to Kerwin. The capcom’s advice to modify their language again fell on deaf ears, as a few more “unscientific” words were uttered.

On their first docking attempt, the probe did not engage with the drogue and no fewer than three further tries were also fruitless. “Pete gave Weitz the controls, depressurized the command module and opened the tunnel hatch,” wrote Conrad’s wife Nancy in her memoir Rocketman. “He and Joe dove head-first into the bank of circuits and gizmos, Pete cussing a blue streak as he sorted through wires, cutting and splicing like a pissed-off Maytag repairman trying to get a dryer to work again.”

Weitz then set about rewiring in the right-hand equipment bay, removing the electrical inter-lock which prevented the main latches from actuating until the capture latches were secure. After an hour or so of re-routing and connecting wires, bypassing electrical relays for the capture latches on the tip of the probe, skinning knuckles (and another bout of undesirable vocabulary) Conrad used the service module’s thrusters to bring the two collars into direct contact, triggering a dozen capture latches in a cacophony like machine gunfire.

Next morning, the crew opened the hatch and Weitz was first to enter Skylab. Pressure checks and air samples gave the atmosphere a clean bill of health.

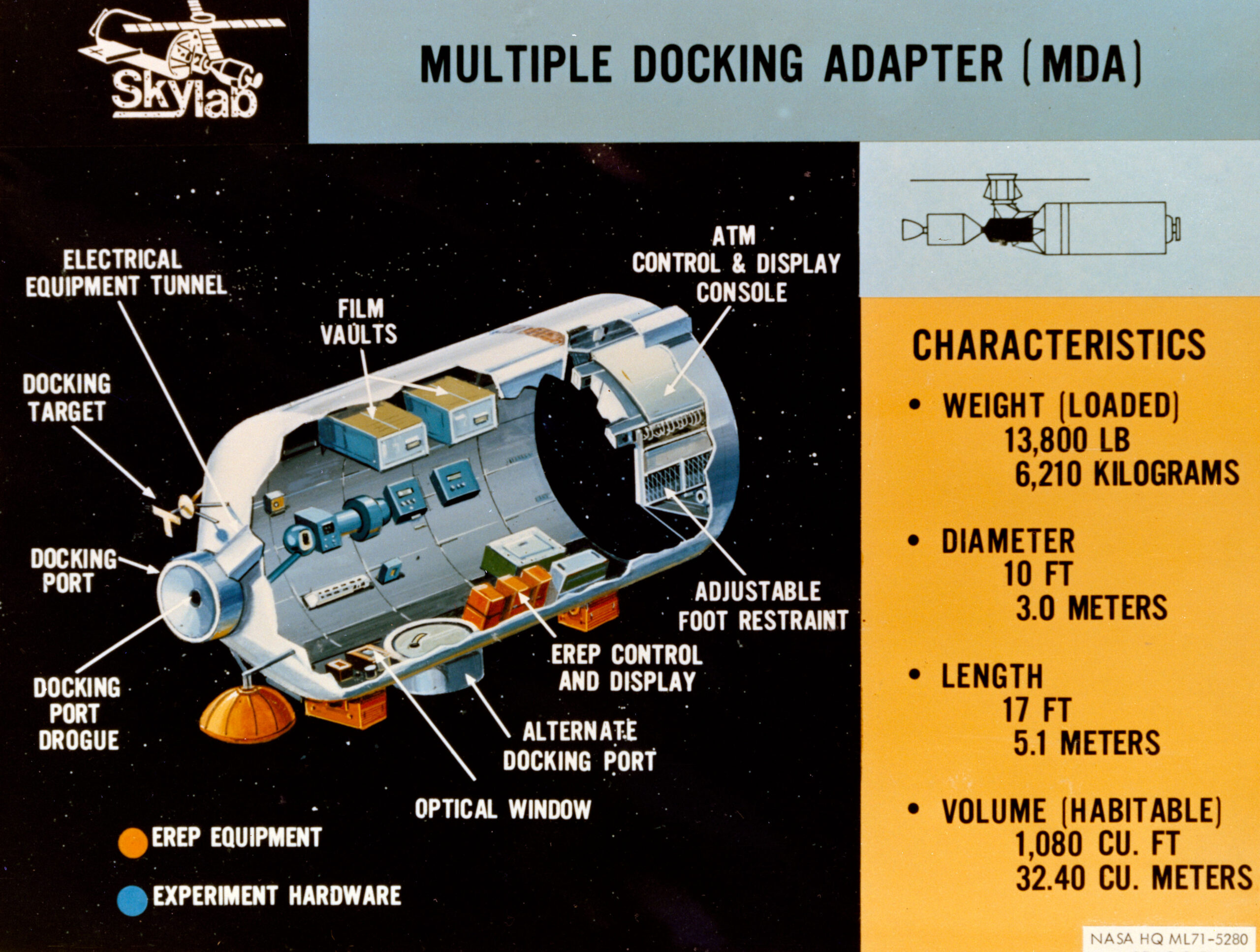

The station’s multiple docking adaptor and airlock were cool, at just 13 degrees Celsius (55 degrees Fahrenheit), but all three men knew that the unprotected interior would be hotter and less comfortable. Conrad and Weitz stripped “down to our skivvies” and opened the hatch into the darkened station to deploy the parasol through the scientific airlock.

“It didn’t take very long until we figured out why people in the Sahara Desert wear a lot of loose clothing,” reflected Weitz, “because soon we had long trousers on and shirts and jackets and hats and gloves and the whole thing.” The temperature was 55 degrees Celsius (131 degrees Fahrenheit)—“rather warm,” the two men noted—and although there was no evidence of toxic gas and the air was safe to breathe, Skylab’s humidity was low and they could only remain inside the stifling oven for 15 minutes at a time. Periodically, they retreated to the multiple docking adaptor for a breather.

At length, the parasol was assembled and its rods were threaded through the scientific airlock into vacuum. Next, the parasol emerged, folding out like a big patio umbrella.

However, one of its four folded arms did not swing out properly and Kerwin, watching from inside the command module, expressed dismay when he saw it had only deployed to cover two-thirds of its required area. “It’s not laid out the way it’s supposed to be,” a dejected Conrad told Mission Control.

The parasol was askew and crinkled in places. Nevertheless, Mission Control assured the astronauts that the wrinkles had probably set in during the coldness of the lengthy deployment, which took place during orbital “night-time” and, as the material heated up in sunlight, it would spread out fully.

“I think the ground noticed the temperatures coming down,” Weitz recalled. “Within an hour, they could tell.” Overnight on 26/27 May, temperatures on the exterior of Skylab began to fall. Eventually, interior temperatures stabilized around 30 degrees (86 degrees Fahrenheit) and the astronauts could even tell where the parasol lay on the outer hull, by running their hands along the station’s inner wall and feeling the difference in temperature.

For the first couple of nights, Conrad and Kerwin elected to sleep in the command module, whilst Weitz tied his sleeping bag in the multiple docking adaptor, “because it was cooler there and you had a lot more room besides.”

It marked a remarkable turnaround of fortunes, less than two weeks after Skylab had almost been lost in its first minutes of flight. Four more weeks of work lay ahead for the astronauts to bring the damaged station to some form of habitability and functionality as a working scientific outpost.

But they were at Skylab to stay. And when Conrad, Kerwin and Weitz returned to Earth in late June, wrapping up a 28-day mission, they would establish a new record for the longest time ever spent in space by any human beings.