When Gregory Peck starred in a movie called Marooned in 1969, he could hardly have foreseen that many of its events would come close to being duplicated in reality a few years later. The movie dealt with a three-man Apollo crew, returning from a multi-month space station stay, whose lives were abruptly thrown into jeopardy by an engine failure just prior to re-entry, rendering them powerless and helpless.

Unable to return to Earth, unable to return to the station and unable to remain in space for more than a handful of days, Mission Control (in the form of Hollywood) came to the rescue and—despite the death of one crewman—most of those involved lived happily ever after. Four years after Marooned screened, a three-member Apollo crew, aboard the Skylab space station for a multi-month stay, came close to mirroring some of the difficulties encountered by Peck and his men.

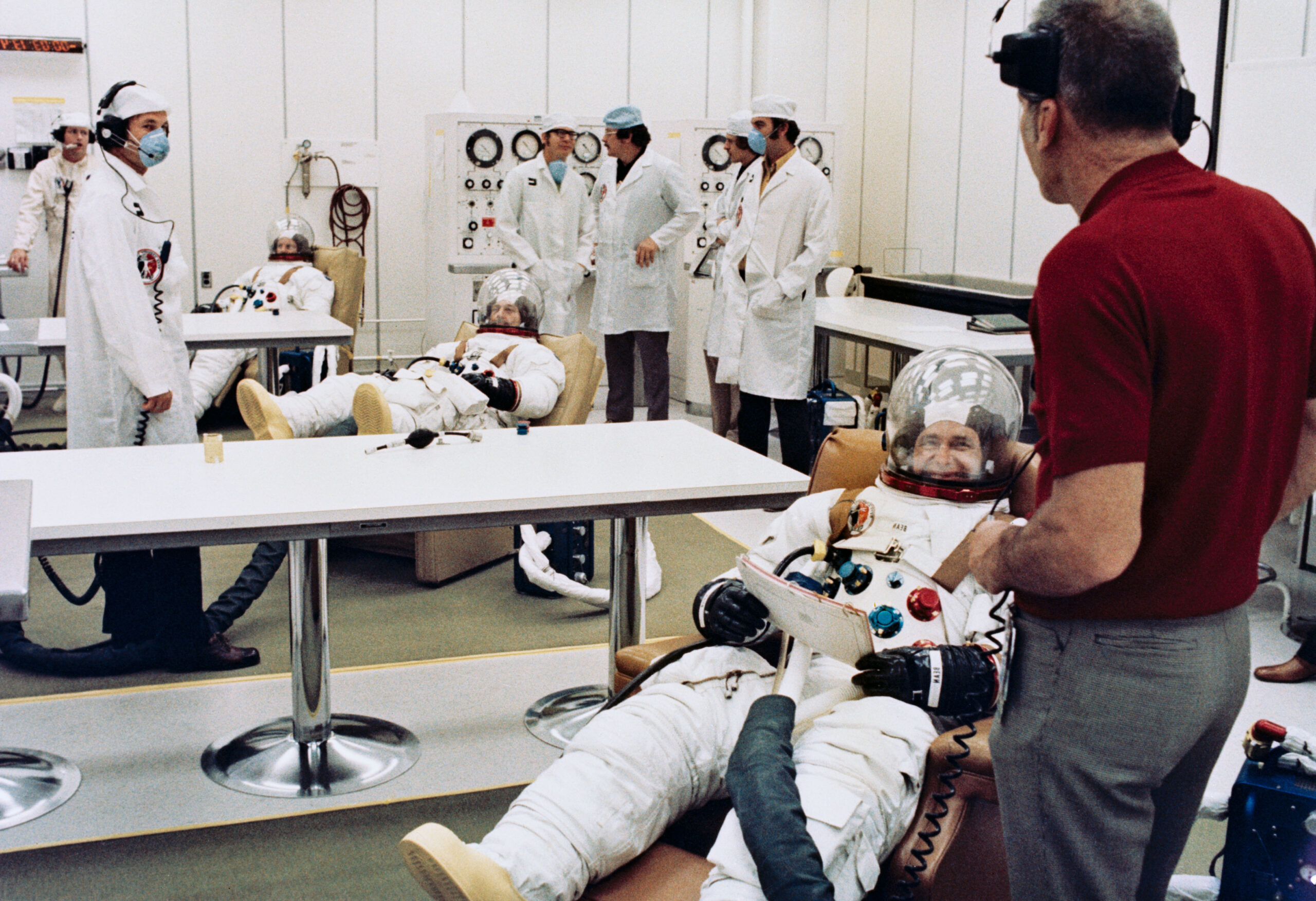

By July 1973, Skylab’s fortunes had turned from despair into triumph. During the station’s launch atop the final Saturn V on 14 May, one of its solar arrays and a critical micrometeoroid shield had been torn away by aerodynamic forces, but a remarkable recovery saw it restored almost to fully operational status by the station’s first crew aboard Skylab 2. A month later, the second Skylab crew—Commander Al Bean, Science Pilot Owen Garriott and Pilot Jack Lousma—prepared for their own launch.

They would spend 59 days in orbit, longer than any other humans before them, and would conduct dozens of experiments and three sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA), totaling more than 13 hours. But Bean’s crew also faced debilitating space sickness, a crippled spacecraft and the very real possibility of a space rescue.

The surprises and challenges which Skylab 3 would bring prompted Bean to sagely remark, years later: “Life is a dance. You learn as you go.”

By the third week in July, NASA settled for 7:11 a.m. EDT on the 28th as the preferred launch date and time, since it offered the best conditions for rendezvous and docking with Skylab during the crew’s fifth orbit, some eight hours after liftoff. That morning, more than 35,000 people crammed the press site, viewing areas and causeways of Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC), but the day dawned dreary and overcast, with only a few lights in the vicinity of Pad 39B and the gigantic Saturn IB booster twinkling in the gloom.

When the astronauts arrived at the pad, Lousma still had to pinch himself. Clambering into the transfer van, encumbered by his bulky suit and oxygen hoses, he had to constantly remind himself that this was no longer a simulation or a drill.

The flashlights of the press were for real. So too were the checkpoints, the last-minute examinations by the flight surgeon, the traditional breakfast of steak and eggs, the biomedical electrodes on their chests and the pressure checks of their suits.

“The technicians…weren’t saying much of anything, because I think they were afraid they would disturb you,” Lousma recalled later. “You could tell that they knew that this was the moment of truth and it was quite clear that this was the day we were all waiting for.”

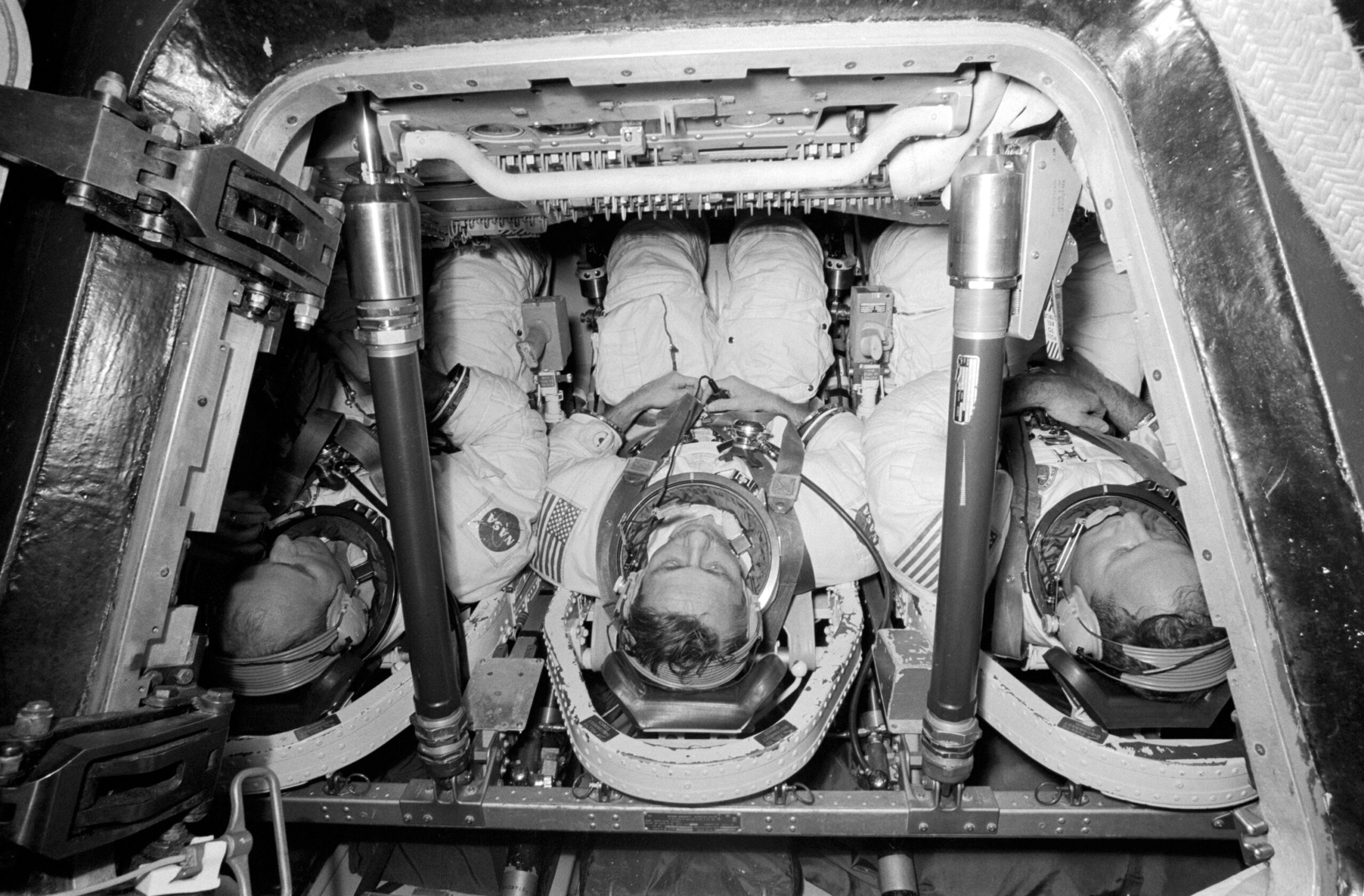

Out at the pad, awaiting his turn to board the Command Module (CM), Lousma noticed that the normal beehive of activity was gone, replaced by eerie silence. “This was the absolute 2001 experience,” he said, “really spacey.”

As the science pilot, occupant of the CM’s center seat, Garriott was last to enter and had a few moments of private reflection, gazing across the Florida landscape. “A fiery rocket would soon take our speed from zero to over five miles a second…in less than ten minutes!” It was a sobering realisation, which Garriott remembered lucidly for decades.

“We’re out there on the launch pad, all by ourselves now,” remembered Lousma, “and we can feel the [Saturn sway] in the breeze a little bit and we’re hoping for good weather. We’re there for about two and a half hours before liftoff, helping the ground crew check out the spacecraft. I fell asleep for a little while…”

From the press site, CBS anchorman Morton Dean relayed live commentary to a rapt audience. Next to him sat former astronaut Wally Schirra, the network’s special expert consultant.

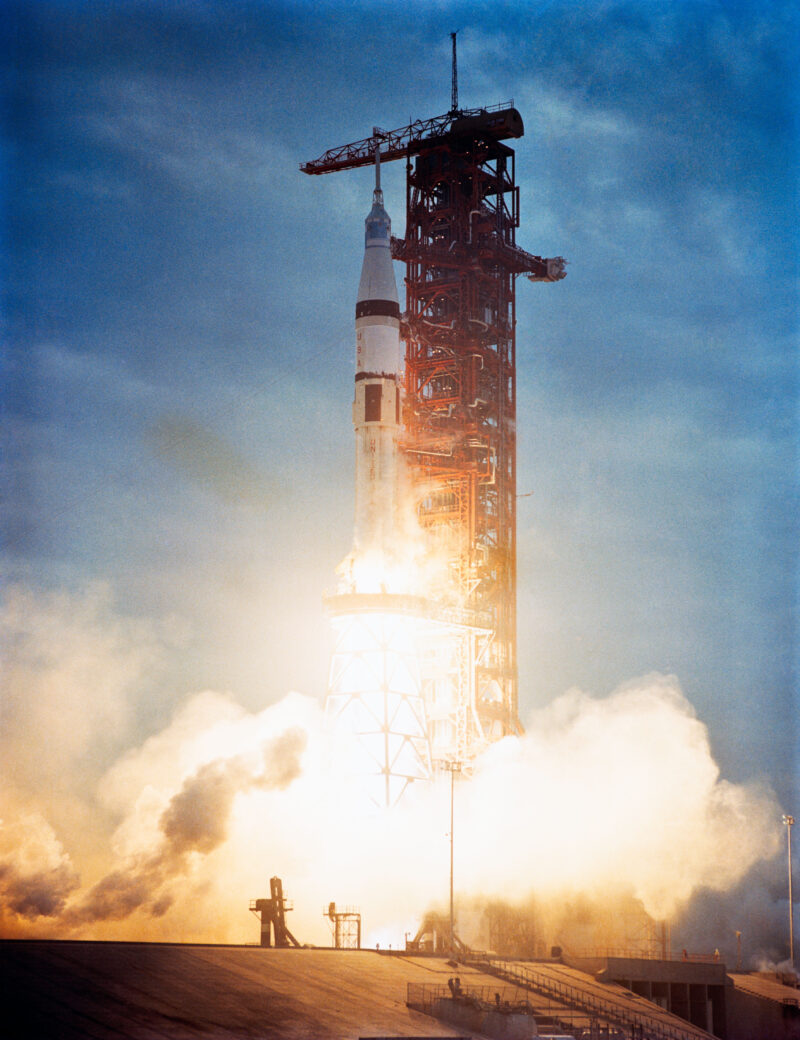

“T minus 40 seconds,” Dean intoned, as television images showed the Saturn IB rocket, scarcely visible in the early morning murk. A few searchlights glimmered through the pre-dawn darkness.

“The spacecraft commander has now made the final guidance alignment,” he continued. “That’s the final action to be taken by the crew on-board the spacecraft until after the launch. T minus 30 seconds…the eight first-stage engines will ignite at 3.1 seconds in our countdown. They’ll be held down while thrust is built up at the zero mark, at which time we’ll get liftoff…”

Dean’s voice notched up an octave as he prepared his audience for the big event and those final few seconds before the mighty Saturn was set to tear itself loose from Earth: “T minus ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four”—then a tongue of brilliant orange flame erupted from the base of the booster and licked at the metallic trusses of Pad 39B’s milk stool—“three, two, we have ignition sequence start, all engines are running”—as the eight H-1 engines roared to near-full power, almost obscuring the rocket from view with their glare—“we have a liftoff…and the second manned crew has cleared the tower!”

From his couch, Lousma noticed a very definite “heavy vibration” at the instant of liftoff. This sensation very quickly damped out, but the initial “chugging” of the Saturn IB did little to disguise the tremendous acceleration, which peaked at around four and a half times the force of gravity.

As the S-IB first stage expended its load of propellant and separated, the three men were greeted by a temporary silence, as they coasted for a while, before being jarred by the detonation of explosive charges, then the seat-of-the-pants push as the single J-2 engine of the S-IVB second stage took over and continued the boost into orbit.

Through his window, Lousma saw a circular “fan” of debris, glinting in the sunlight. For Garriott, the sensation of being pressed into his seat at several times his Earthly weight to suddenly floating in his harness was electrifying.

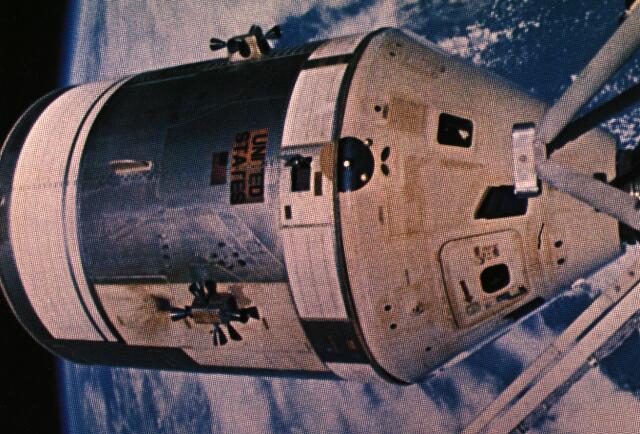

Ten minutes after leaving Florida, the second Skylab crew were in space, primed for an eight-hour chase of the station and a late-afternoon rendezvous and docking. Yet problems did not take long to catch up with the mission.

About three hours into the flight, Bean reported “some kind of sparklers” streaming past one of the windows after the first firing of Apollo’s big Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine. Lousma spotted it first and called Garriott to take a look.

“I looked out his window and here came what looked to be the nozzle of one of the reaction control thrusters just floating by the window,” Garriott recalled. “It couldn’t have come off the spacecraft…the propellant line to that nozzle had sprung a leak, so when the propellant comes out of the fuel line, it then freezes on the nozzle and then after a certain amount of it escapes, it acquired the shape of the nozzle. What floated away was an “ice sculpture” of that reaction control thruster!”

A few seconds later, Bean was startled by the blaring of a master alarm, indicating low temperatures in one of the ship’s Reaction Control System (RCS) thruster quads. All three men realized that a propellant leak of either hydrazine or nitrogen tetroxide had most likely occurred in “Quad B”, one of four quads of RCS thrusters, spaced 90 degrees apart around the Service Module (SM).

It was not good that it had come during the rendezvous with Skylab and so early in their mission. They quickly set about shutting down the entire quad on Lousma’s side of the spacecraft. The data revealed a clear drop in pressure, as both the hydrazine and pressurizing helium rapidly fell to off-scale lows.

What Garriott and Lousma had seen in their “ice sculpture” was the effect of a small leak, which slowly crawled around the inner surface of the thruster and froze into the shape of the exhaust cone. This sculpture was then shaken loose when the thruster next fired.

In their book Homesteading Space, David Hitt, Owen Garriott and Joe Kerwin noted that, due to the “reduced authority” of only having three sets of RCS quads at his disposal, Bean was obliged to pulse the remaining thrusters for longer periods to achieve a perfect rendezvous. “It really incapacitated us a lot,” Bean recalled. “The main effect we had was any time I did anything, we went off-attitude in the other axes.”

During training, their instructors had thrown them hundreds of failures and they managed to overcome each one without so much as a blink of the eye or a bead of sweat. Now, said Bean, “we realized we were lucky we didn’t have some sort of explosion and blow that leaky quad thruster right off and really have a problem.”

The situation was compounded by the reality that, in 1973, devices to precisely measure a spacecraft’s closing range rate with the target had not yet been invented. Garriott, tasked with helping Bean to stick to the correct trajectory, had trained to use two range measurements from the on-board radar transponder at two different times, then dividing the range difference by the time difference. It was far from perfect and quickly became apparent that it was not slowing them down sufficiently to complete the rendezvous with Skylab.

Conversely, added Bean, “one of the worst things you could ever do was slow down too much, because then you had to use fuel to get closing again, all the timing’s off, you came into daylight too soon—all these things were going on in my mind.” He lauded Garriott as “a great back-of-the-envelope guy”, capable of making accurate and rapid calculations and recommendations, but doubted his crewmate’s reminders that they were closing too fast and needed to apply more braking.

They were indeed closing too fast. Had it not been for Garriott’s admonitions, they would have closed too rapidly and sailed straight past Skylab, which would have forced a re-rendezvous and unnecessary waste of propellant. The astronauts’ first view of Skylab came at a distance of 400 miles (640 kilometers) and docking occurred nine hours into the mission, with the mighty Amazon River as a spectacular backdrop.

Despite the good health of the station and—it seemed—the Apollo spacecraft, the first major obstacle quickly reared its head, when all three men fell foul of space sickness. First was Lousma, who experienced symptoms soon after reaching orbit. He took an anti-motion-sickness pill and felt well enough to fulfil his duties during rendezvous.

However, Bean and Garriott soon reported stomach “awareness” and were unable to move quickly around Skylab. At length, even with the benefit of anti-motion-sickness medication, it was becoming increasingly difficult for the astronauts to prevent themselves from becoming ill.

“We hadn’t spent a lot of time in…a volume [this large],” Lousma said. “It was mostly in confined quarters, where you don’t have to move very much, but now we were climbing out of the command module and going through the tunnel into this big volume and we had all kinds of room to operate in and move around in.”

By the morning of 29 July, after an unpleasant night’s sleep, breakfasts were partially uneaten and the astronauts were behind on their timeline. A concerned Bean asked Mission Control to allow them to rest for a while and to move their first off-duty day from 3 August to 30 July; additionally, it was decided to postpone their first EVA by 24 hours.

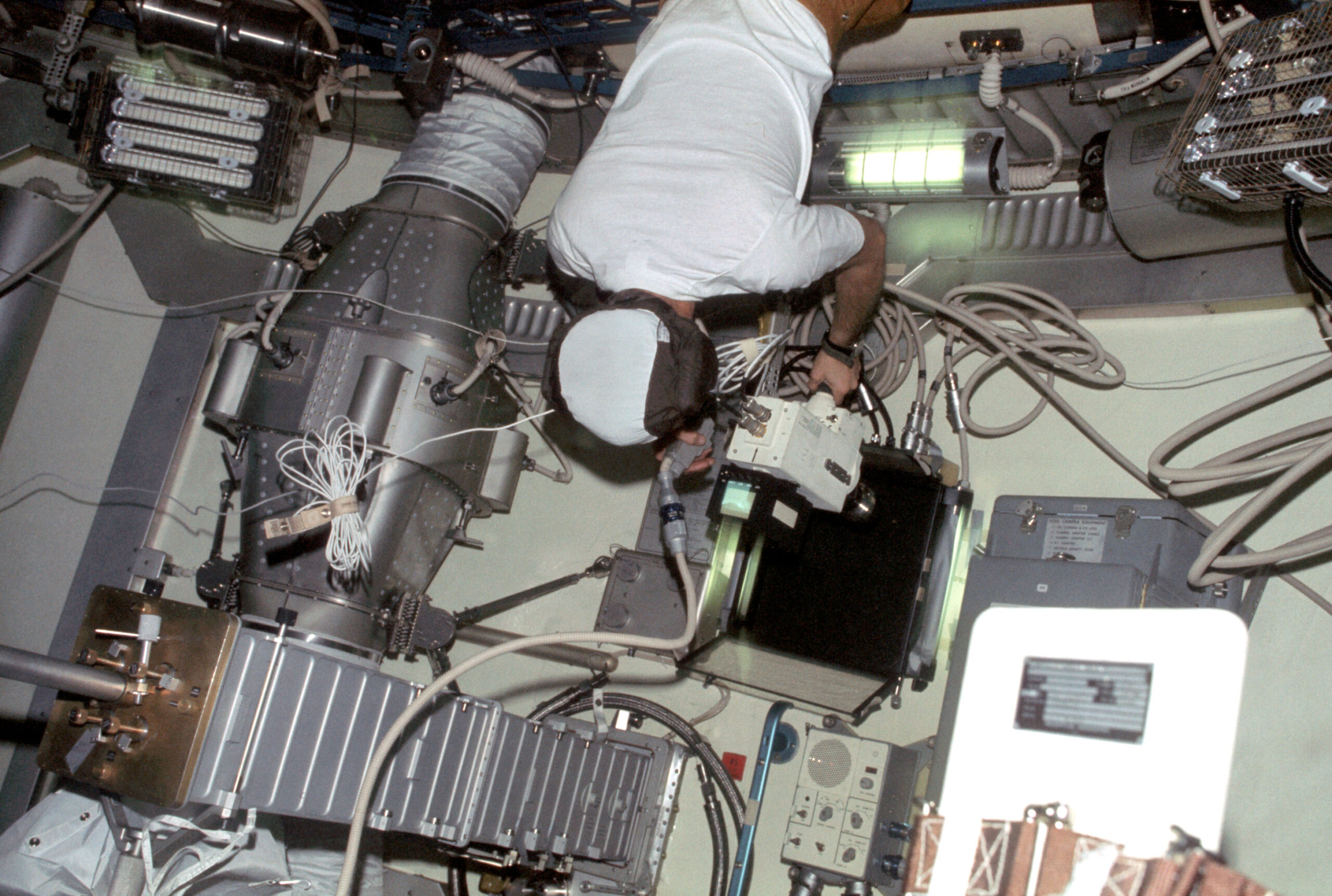

Originally, according to a detailed timeline published by NASA a few weeks earlier, three EVAs were planned for the mission—on 31 July, 24 August and 19 September—to install and retrieve film from Skylab’s Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). The first EVA was especially critical, as it would deploy a backup sunshade to help cool Skylab.

Lousma was perplexed at his unpleasant reaction to the space environment. He was a Marine Corps aviator, used to sickening aileron rolls and other stomach-churning maneuvers and had trained extensively in rotating chairs, making deliberate head movements to induce nausea and “condition” himself.

It all appeared to have been for nothing. “On the ground, we were one of the most resistant crews to that kind of experience,” he explained, “but when we got in there, we were one of the least resistant!”

“Now, Alan and I never got frankly sick,” Garriott admitted, “but we were feeling what I call lethargic…really not up to speed, not ready to charge full-speed like you wanted to do.” They paced themselves for the first couple of days, limiting movements and changes of orientation, taking time to rest, stopping and shutting their eyes whenever they felt ill, then going back to work when, as Lousma put it, they had allowed their “gyros to unspin”.

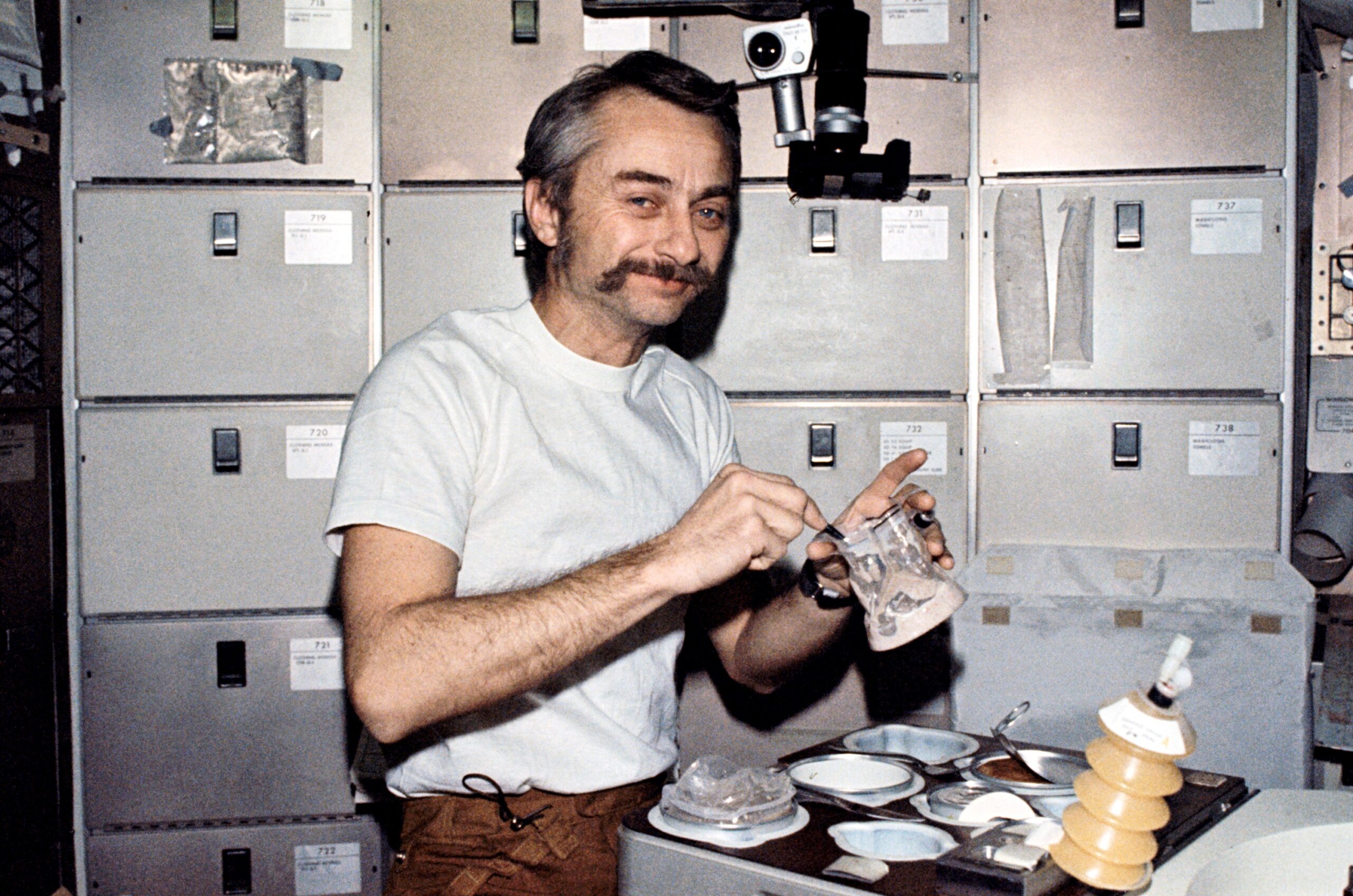

As August began, all three men were in far finer spirits—with Bean demonstrating space gymnastics to his television audience and Lousma admitting that the food tasted better—although mission managers elected to postpone the EVA for a second time. Smaller-sized meals were recommended to avoid nausea, but Bean argued that it was the timeline which conspired against them. Everything they did took time, even tracking down heads for their shavers, and as Mission Control sent them additional work to do, they found themselves bogged down with other tasks.

“Losing” things, in fact, was a constant problem throughout the mission, since finding them again was quite unlike the chances of finding a lost item back on Earth. “We always seemed to look on hard surfaces,” said Garriott, “where we would normally have left it, but three-dimensional space is just too difficult to search visually.”

After a while, they learned to start by checking the intake duct of the station’s air-circulation fan, where lint and debris—and, quite often, pens, pencils and other objects—would be rediscovered. Lousma turned the familiar Earthly problem upside down: instead of looking on the tops of places to find lost items, he inverted his frame of reference to look underneath. “When you’re upside down,” he explained, “and look for something, you look at those places that you don’t normally see, or that your eye doesn’t get drawn to, because you tend [on Earth] to expect things to be sitting on something.” By adopting an unusual perspective, he “de-tuned” his normal search strategy.

Aside from the time consumed by losing and having to find things, the pace of that first week aboard Skylab was hectic and Bean was convinced that zooming around, unpacking equipment and supplies and activating systems was aggravating their malaise. “We were not eating on time,” he explained, “we were not getting to bed on time and we were not exercising.” All three were crucial in ensuring a smooth adaptation from an Earthly lifestyle to the new environment and Bean strongly advised the next crew to prioritize those over the activation of Skylab.

At last, around six days after launch, they finally began to hit their stride.

Then, as will be seen in next week’s AmericaSpace history story, a potential calamity arose which threatened to derail the whole mission.