Scientific conferences play an undervalued, yet essential, role in the exploration of the Solar System. Since the end of the Apollo program, data on the planets and their moons have been collected by a handful of robots built in sterile cleanrooms. However, we would not learn anything from this information without people. The teams who operate these spacecraft are spread across the country, and they rarely meet in person. Annual symposia provide a unique opportunity for them to reconnect and to pass down their knowledge to the next generation, who will carry on humanity’s gradual advance into space.

While every meeting has devotees, the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) occupies a special place in the hearts of the scientists who study the planets. This five-day event is a confluence of the 60-year history of spaceflight; the latest findings from operational missions; and researchers’ aspirations for the coming decades. The American Geophysical Union (AGU)’s annual meeting takes a broad look at all of Earth and space science, while smaller conferences, such as the Division for Planetary Science (DPS), permit attendees to delve into narrow topics. LPSC occupies the middle ground, providing a holistic look at all of the distant worlds which NASA and its partners are exploring.

LPSC has a long and colorful history which stretches back to the legendary Apollo era. NASA organized the first meeting, which was dubbed the Apollo 11 Lunar Science Conference. Its original purpose was to allow the first scientists who were given Moon rocks to share their findings with each other. It proved to be a great success, and NASA decided to fund subsequent meetings on an annual basis. These follow-on conferences were organized by the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), an independent research lab which is funded by the government.

The history of LPSC mirrors the history of space exploration writ large. The initial meetings were exclusively focused on the Moon, but they expanded in scope to first encompass Mars and then the outer planets as NASA shifted from Apollo to a smaller and broader portfolio of human and robotic missions. For the first thirty years of LPSC’s existence, the conference was held at the Johnson Space Center, and it featured a Texas-themed chili cook-off. Both of these highlights disappeared after the September 11th terrorist attacks due to liability and security concerns, and the meeting shifted to a commercial hotel in Houston. LPSC has also grown alongside NASA’s planetary exploration program. The number of people in attendance has increased tenfold since 1970, and sudden spikes in LPSC’s size coincide with the debuts of prominent missions such as Magellan, Galileo, and the Spirit and Opportunity rovers.

Many scientists have chosen the meeting as the place to unveil their most significant discoveries. As the late lunar scientist Paul Spudis once said, “When you want to look at the science highlights, I say pick up any planetary science textbook because virtually anything in that was first reported at this conference.” The ideas which were proposed here include John Wood’s lunar magma ocean hypothesis, which is the basis for our understanding of the early Solar System; the initial arguments over the fossils (or lack thereof) in the infamous Martian meteorite ALH84001; the first evidence for ancient liquid water at Opportunity’s landing site; and the presence of the chemical building blocks for life in the OSIRIS-REx samples.

While a scientist’s academic calendar revolves around conferences, today’s iteration of LPSC is exceptional and unique for a handful of reasons. The first is its connection to NASA’s history. While LPSC has been forced out of downtown Houston due to its increasing size, it is still straightforward for scientists to visit the Johnson Space Center while travelling to or from the airport.

Many younger students have not seen a Saturn V rocket or a Moon rock; LPSC is a convenient way to expose them to these icons of spaceflight. Furthermore, it is often possible to have one-on-one conversations with the scientist-astronauts who flew those vehicles at the conference itself! Likewise, the meeting is attended by scientists of all ages, from precocious high schoolers to “retired” professors who maintain an interest in the field. Standing amongst these people, it is hard not to feel a connection to the rich historical tradition which has accumulated over the past six decades.

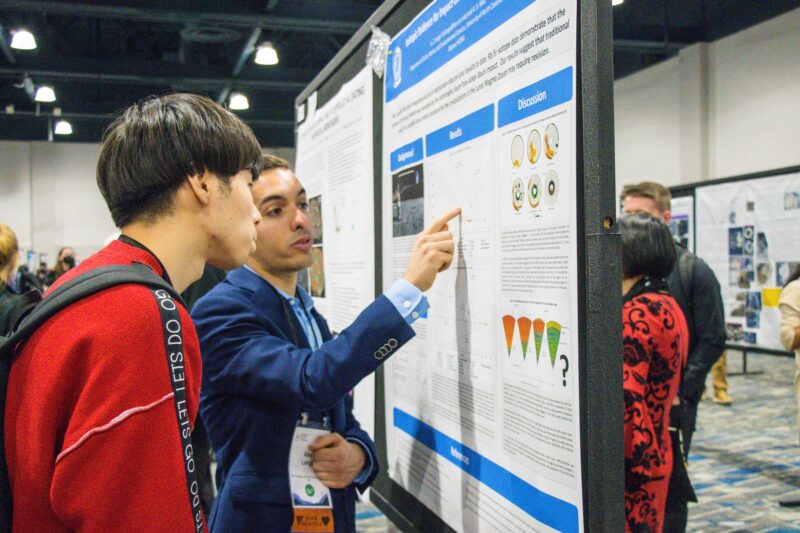

LPSC is also an ideal venue to learn about the latest discoveries about the Solar System. Throughout the week, five sessions of simultaneous presentations are held inside cavernous ballrooms. For instance, at the last conference, scientists had to choose between listening to talks on Artemis mission planning, solar wind samples from the Genesis mission, volcanic activity on Venus, groups of minerals on Mars, or the ocean of Enceladus. “Session-hopping,” where audience members race between rooms to catch their most anticipated talks, is common. In addition to the official presentations, there are also dozens of breakout meetings, which are held in smaller rooms. These gatherings are typically more personalized. For instance, a group of students might discuss networking strategies, or the science team for a specific spacecraft or instrument might plan the next stage of their mission.

LPSC is particularly beneficial for students. Over its history, the Lunar and Planetary Institute has done excellent work to keep registration fees low. Getting through the door of most major scientific conferences costs around $1,000; despite the fact that NASA has substantially reduced its financial contributions since 1970, LPSC’s registration fees are in the $500 range. LPI has accomplished this herculean task by keeping the conference in one place, rather than moving it around the country. The Woodlands, the suburb of Houston which hosts the conference, is remote, but it is also substantially cheaper than any of the other venues which were evaluated [1].

Additionally, the meeting’s organizers prioritize giving early-career scientists an opportunity to present their work in front of a large audience. In fact, a large proportion of oral presenters are students; older scientists often present in the poster hall instead. Unlike any other meeting, LPSC has a dedicated session on mission concepts. Whenever NASA selects a new spacecraft for flight, you can usually trace its origin back to an LPSC abstract.

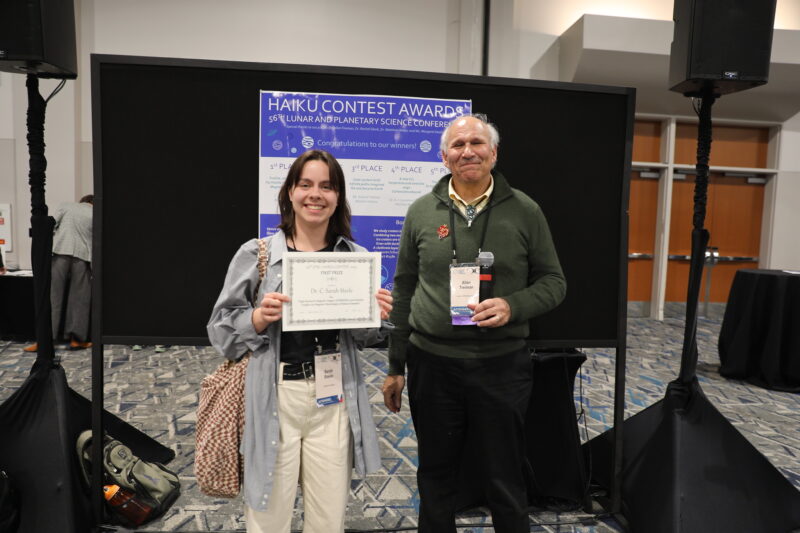

Finally, LPSC has a reputation for being fun. Most scientific conferences are managed by large nonprofits or professional societies, which churn out conference programs in a highly structured, standardized format. In contrast, LPSC is LPI’s flagship conference, and the meeting staff invest a disproportionate amount of effort into making it a unique experience. LPSC has enabled the growth of traditions which cannot be found anywhere else. Many scientists elect to write their conference abstracts in haiku form, and prizes are awarded for the best poems. A paddleboat race is always held on the canal adjacent to the hotel, and the Universities of Arizona and Hawaii hold legendary parties for their alumni. Because the conference remains in a fixed location, restaurants such as Grimaldi’s Pizza have morphed into iconic landmarks.

Planetary Society writer Emily Lakdawalla summarized the conference’s value splendidly. “LPSC is different, somehow,” she wrote [2]. “People don’t ordinarily express their love for conferences, but people love LPSC.” Speaking personally, the meeting feels like a family reunion of sorts. It is an opportunity to connect with dear friends who you only see once per year, and to discuss your passion for space science with people who share that interest. As a young scientist, I hope to one day bring my students to the event so that they can have this experience for themselves and pass it down: generation to generation, Earth to the stars.

Unfortunately, LPSC is facing a more uncertain outlook than at any time in its 57-year history. While NASA initially covered the cost of the entire conference, it has gradually reduced its financial contribution over time. This year, the agency announced its intention to withdraw the last of its monetary support. This could increase registration fees, though the magnitude of their growth may not be as dire as many scientists fear because NASA’s funding contribution has decreased over the years. Some researchers have also expressed concerns about the long-term preservation of conference abstracts on LPI’s website [3]; discussions about resolving this issue are ongoing.

This challenge should not be taken lightly. If there are not enough attendees to break even financially, then registration fees will need to increase; this, in turn, will drive down attendance further. It is a vicious positive feedback loop which can lead to the downfall of even the most beloved and longstanding events.

LPSC is a living piece of history. No other scientific conference possesses its rich heritage, nor its evolving connection to our space program. Predictable career paths, a shared identity, and continuity of purpose are all essential for building a multigenerational bridge into the Solar System. If these elements are not in place, any transitory success which the U.S. space program achieves may not be sustained. For this reason, it is imperative that planetary scientists continue to attend LPSC so that this event can be preserved for future generations of students and explorers to enjoy.

Thank you for this important piece on LPSC. I hope word gets out enough so this important endeavor will continue to be supported long into the future.

No problem! Every piece of positive coverage is helpful. I have been to LPSC several times, so preserving and improving it is one of the top issues on my mind right now.