Following last week’s successful hot-fire test of the nine first-stage engines of its Falcon 9 v1.1 rocket, SpaceX—the Hawthorne, Calif.-based launch services organization, headed by entrepreneur Elon Musk—has announced that it will delay the launch of its third dedicated Dragon cargo mission (CRS-3) toward the International Space Station (ISS). Liftoff of the Falcon 9 rocket was scheduled to occur from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., on Sunday, 16 March, at 4:41 a.m. EDT (8:41 a.m. GMT), but has been postponed by at least two weeks. “To ensure the highest possible level of mission assurance and allow additional time to resolve remaining open issues, SpaceX is now targeting 30 March for the CRS-3 launch, with 2 April as a backup,” the company revealed yesterday (Thursday). “These represent the earliest available launch opportunities given existing schedules and are currently pending approval with the [Eastern] Range.”

This launch is the first Dragon mission by SpaceX for a year, following March 2013’s CRS-2 flight. The company received a $1.6 billion Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract from NASA in December 2008 to launch at least 12 cargo missions to the ISS by 2016, delivering about 20,000 pounds (44,000 kg) of equipment and provisions to the station’s incumbent crews. After a successful Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) demonstration mission in May 2012—in which SpaceX became the first commercial entity ever to dock one of its vehicles to the ISS—the company moved from strength to strength, launching its first dedicated flight (CRS-1) in October 2012 and its second (CRS-2) in March 2013. Both missions validated Dragon’s stated aims of delivering cargo to the station, remaining berthed for about a month, then returning safely to a parachute-assisted splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

The CRS-3 mission has been waiting in the wings for many months, but has been extensively delayed, partly due to the sheer volume of other Visiting Vehicles to the ISS. At one point, late last year, both it and Orbital Sciences Corp.’s first dedicated Cygnus resupply mission (ORB-1) were co-manifested for the same mid-December target date. It was ultimately decided to fly Cygnus ahead of Dragon in the December slot, but this plan ultimately came to nought when an external cooling loop problem aboard the ISS forced two U.S. EVAs over Christmas week to remove and replace a faulty pump module. Finally, on 9 January, the ORB-1 mission got underway and its conclusion last month cleared the way for the upcoming Dragon flight.

Ahead of the launch, SpaceX last weekend rolled the Falcon 9 v1.1 out to the pad to conduct a “hot-fire” test of its nine Merlin 1D first-stage engines. According to Spaceflight101, the static-fire test was originally planned for 7 March, but poor weather conditions pushed the rollout of the Falcon 9 to SLC-40 until early on the 8th. Several hours of delays were then enforced, due to technical difficulties, but the hot-fire was successfully completed and the vehicle returned to its hangar.

Assuming that SpaceX goes ahead with a revised launch date of 30 March, the ignition of the nine Merlin 1D first-stage engines on the Falcon 9 v1.1 will commence at T-3 seconds, producing 1.3 million pounds (590,000 kg) of thrust. This is about 200,000 pounds (90,000 kg) greater than the propulsive yield of the Falcon 9 v1.0, which delivered previous Dragons into orbit. The Merlin 1Ds will push the vehicle uphill for 180 seconds, their thrust gradually rising during ascent to 1.5 million pounds (680,000 kg) in the rarefied high atmosphere. “Unlike airplanes, a rocket’s thrust actually increases with altitude,” noted SpaceX. “Falcon 9 generates 1.3 million pounds of thrust at sea level, but gets up to 1.5 million pounds of thrust in the vacuum of space. The first-stage engines are gradually throttled near the end of first-stage flight to limit launch vehicle acceleration as the rocket’s mass decelerates with the burning of fuel.”

Immediately after clearing the SLC-40 tower, the Falcon 9 v1.1 will execute a combined pitch, roll, and yaw program maneuver to establish itself onto the proper flight azimuth for the injection of Dragon into low-Earth orbit. Eighty seconds into the ascent, the vehicle will pass Mach 1 and experience a period of maximum aerodynamic stress (known as “Max Q”) on its airframe. The Merlin-1Ds will continue to burn hot and hard, finally shutting down at T+3 minutes, and the first stage will be jettisoned about five seconds later.

This launch is indicative of the steady maturity of SpaceX technology as it strives to develop a fully reusable Falcon 9, whose two stages will ultimately be able to complete their respective boost phases, propulsively return over water, and touch down on extendable landing legs back at their launch site. The system was trialed, with mixed results, during the inaugural flight of the Falcon 9 v1.1 last 29 September, but it experienced an uncontrollable roll during its descent. This caused the final burn of the center Merlin 1D engine to be shortened, due to the centrifuging effect on propellant against the tank walls, which damaged the baffles and allowed debris to enter the engines. Landing legs were not flown aboard the second Falcon 9 v1.1 mission, which launched the SES-8 communications satellite in December, or aboard the third mission, which launched Thaicom-6 in January.

The Falcon 9 assigned to the CRS-3 mission boasts four fold-out landing legs, made from carbon-fiber and aluminum honeycomb, on its first stage, which will be deployed during the controlled descent. Although a touchdown on land is not yet planned, SpaceX hopes to touch down on water. Shortly after the burn-out and separation of the first stage, it will execute a maneuver with its cold-gas attitude-control system to establish an “engine-forward” orientation. Three of the nine Merlin 1Ds will briefly fire to effect braking during the re-entry process and the four landing legs will be deployed using high-pressure helium once in atmospheric flight. The legs span 60 feet (18 meters) when fully deployed and the entire assembly weighs about 4,400 pounds (2,000 kg). Assuming that the vehicle does not again fall victim to excessive roll motions, the center Merlin 1D will ignite shortly before it makes a gentle impact with the Pacific Ocean. Elon Musk has stressed that although an attempt will be made to retrieve the first stage from the ocean, the system remains experimental in nature and he does not anticipate success for at least the first several attempts.

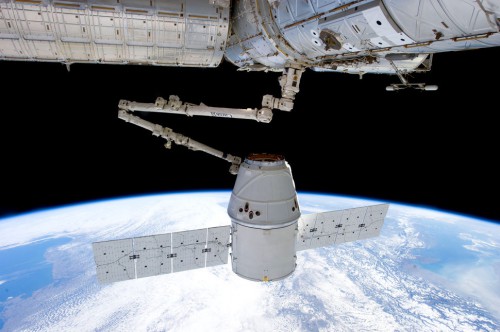

Meanwhile, with the first stage gone, the turn will come for the Falcon 9 v1.1’s restartable second stage, whose single Merlin 1D Vacuum engine—with a thrust of 180,000 pounds (81,600 kg)—will fire to deliver Dragon into low-Earth orbit. Following separation from the vehicle, the resupply craft will unfurl its electricity-generating solar arrays, deploy its Guidance and Navigation Control (GNC) Bay Door to expose critical rendezvous sensors, and begin a complex series of maneuvers to reach the ISS. It will approach the station along the so-called “R Bar” (or “Earth radius vector”), which provides an imaginary line from the center of Earth toward the ISS, effectively approaching its quarry from “below.” In so doing, Dragon will take advantage of natural gravitational forces to brake its final approach and reduce the overall number of thruster burns it needs to perform.

By the third day of autonomous operations, it will have drawn into the vicinity of the space station and several “Go/No-Go” polls of flight controllers will permit it to gradually reduce its distance to about 30 feet (10 meters), placing it within range of the 57.7-foot (17.4-meter) Canadarm2 robotic arm. The spacecraft will then be captured by the incumbent Expedition 39 crew—which, by the end of March, will have increased to its full, six-man strength of Commander Koichi Wakata of Japan and Flight Engineers Mikhail Tyurin, Aleksandr Skvortsov, and Oleg Artemyev of Russia, together with U.S. astronauts Rick Mastracchio and Steve Swanson—and berthed onto the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Harmony node. Berthing is anticipated about 50 hours after liftoff.

Thanks to the enhanced performance of the upgraded Falcon 9 v1.1, the CRS-3 mission will transport a record-sized cargo of 3,480 pounds (1,580 kg) to the station. This includes a powered General Laboratory Active Cryogenic ISS Experiment Refrigerator (GLACIER), which provides for the transportation and preservation of samples at temperatures between -160 degrees Celsius (-301 degrees Fahrenheit) and 4 degrees Celsius (39 degrees Fahrenheit). Dragon will also carry a pair of Microgravity Experiment Research Locker Incubators (MERLIN), both of which will supply a refrigerator/incubator at temperatures from -20 degrees Celsius (-4 degrees Fahrenheit) to 48.5 degrees Celsius (119 degrees Fahrenheit). Also aboard Dragon will a new Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) space suit to replace the unit which malfunctioned and allowed water seepage into the helmet area during Luca Parmitano’s ill-fated EVA-23 in July 2013. The problematic suit will be returned to Earth aboard Dragon. Other payloads hitching a ride into orbit on CRS-3 include the Optical Payload for Lasercomm Science (OPALS) to demonstrate high-bandwidth space-to-ground laser communications and the High-Definition Earth Viewing (HDEV) payload of four commercial HD video cameras to film Earth from multiple angles. Both of these payloads will be robotically installed onto the exterior of the ISS.

Following berthing, it is expected that Dragon will remain attached to the ISS for about a month. With Orbital Sciences Corp.’s second dedicated Cygnus mission (ORB-2) tentatively scheduled for launch in early May, and slated to also utilize the Harmony nadir port, any further delays threaten to disrupt the already tight schedule of Visiting Vehicles for the remainder of 2014. Present plans envisage Cygnus flights in May and October, with Dragon missions in July and November, although this remains subject to flux. In announcing the delay to the CRS-3 launch, SpaceX noted that “both Falcon 9 and Dragon are in good health,” but stressed that “given the critical payloads on board and significant upgrades to Dragon, the additional time will ensure SpaceX does everything possible on the ground to prepare for a successful launch.”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » ISS » COTS » CRS-3 »

Excellent article Ben! One addition/correction: the landing legs will be deployed 10 seconds into the landing burn of the center Merlin 1D engine, not between the re-rentry burn and the landing burn. Keep up the great work! 🙂

Excellent information and so detailed. I can’t wait for a man – rated version of Dragon to fly. We need to quickly eliminate our dependence on Russian to get our crews to the ISS

Ben,

Why no mention of the reason for the delay…. From Aviation Week 3/17…

“We’ve had some issues with payload contamination that we will be addressing,” he said. “We’re going to have to assess that and replace some parts and get the rocket ready for launch again. Our current launch date right now I believe is March 30.”….

I wondered how big a problem sabotage was going to be for SpaceX….I guess now we know.