Early in the spring of 2001, the mission of STS-107 first sparked my interest, for two reasons. One was the fact that its seven-strong crew was relatively inexperienced—like that of Challenger, none had flown more than once in space—and the other was that it represented the first “stand-alone” scientific research flight performed by the shuttle for several years. With most of the missions around it devoted to International Space Station construction, Commander Rick Husband’s flight seemed oddly out of place. “Why do you want to write about that one?” came the reply from the magazine Spaceflight, when I proposed an article on STS-107. “It’s just a research mission?” Nonetheless, Spaceflight graciously supported my request to interview Husband and the article was published in October 2001. More than a decade later, I am glad that I took such an interest in STS-107, the final flight of Columbia and a mission which suddenly and drastically altered humankind’s trajectory in space as few other missions have ever done, for better and for worse.

Rick Husband and I spoke for half an hour on the evening of 3 April 2001, over the telephone from his Houston office. I was in Liverpool, studying for my master’s degree at the city’s university, a couple of miles from the birthplace of Beatlemania. I could scarcely have imagined that Husband and his crew would be engulfed in the shuttle program’s second disaster in less than two years’ time, as they hypersonically knifed their way back through the atmosphere after an enormously successful 16-day flight. It is to my lasting regret that I never got the chance to tape record my conversation with Husband—only a page of hand-scribbled notes, later transferred onto a computer, exist as a memory—but I do recall the opening words of our exchange, when I realised I was talking one-to-one with a real, live astronaut. It is funny how certain things stand out about a person, and others do not, for my first impression was the depth of Husband’s voice and his humor.When NASA PAO contacted me in March 2001 to agree to the interview and gave me a telephone number to call at a specific time on that day, I thought for an instant that someone was pulling my chain. Surely I wouldn’t be connected directly to Husband’s office … would I? I would certainly speak to his secretary or a PAO official in the first instance. I would be asked for my list of questions, such that Husband could be prepared in advance. As I dialed the number, I felt a twinge of excitement and nervousness. My hand-written notes and list of questions trembled in my hand.

Someone answered. Deep voice, Texan drawl. “Rick Husband.”

Oh, hell, I thought, it’s really him. Yet my stupidity still made me unsure.

“Good afternoon. Colonel Husband?”

“This is he.”

“Colonel Husband, good afternoon. My name is Ben Evans and I’m … ”

“Hi, Ben.” As if he’d known me all my life. That set me at ease.

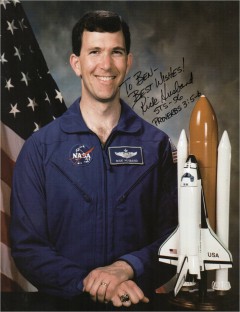

To start the interview, I reiterated thanks to him for a signed photograph that he had sent to me in late 1998, inscribed with the legend “Proverbs 3: 5-6.” It seemed a logical place to start the interview and Husband seemed pleased that I had remembered the quote—Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding / In all your ways, submit to Him and He will make your paths straight—as he explained that “God’s blessing and provision” had indeed guided his path since childhood, through engineering college, into the Air Force and test pilot school, into the hallowed ranks of NASA’s astronaut corps, and into the exalted position of being selected to command the space shuttle. I stressed that he was the first pilot since Sid Gutierrez in April 1994 to lead a crew on only his second mission, but Husband brushed it off. Humbly, he said, it was nothing more than being in the right place at the right time.

There was, of course, much more to it than that. Kent Rominger—who commanded Husband’s first mission and served as chief of the astronaut corps at the time of the STS-107 disaster and through the return to flight in mid-2005—later recalled that the selection had more to do with his expertise and skill in the cockpit. In her book High Calling, his widow, Evelyn, wrote of Rominger’s recollection that Husband returned from his stint as pilot of STS-96 in June 1999, primed and ready for the commander’s seat. “You really only need to know two things,” reflected fellow astronaut Jim Halsell. “First, we recruited him into the astronaut office because of his wide-known reputation within the Air Force. Second, Rick was offered his own shuttle command after only one flight as a pilot, instead of the standard two. He was that good.” Husband served a spell as chief of safety for the astronaut office, and in December 2000 was named to lead STS-107. Assigned alongside him was pilot Willie McCool, and the pair joined a previously announced quintet as multi-culturally diverse as they were multi-talented: an African-American (Mike Anderson), an Indian-American woman (Kalpana Chawla), two physicians (Dave Brown and Laurel Clark), and Israel’s first spacefarer (Ilan Ramon). These five had been assigned in September 2000. They would support dozens of scientific experiments in the new Spacehab Research Double Module, housed in Columbia’s payload bay, and a battery of instrumentation on the Freestar pallet.

Launch was originally scheduled for August 2001, but was extensively postponed as NASA’s oldest orbiter did not return to the Kennedy Space Center, after a $164 million program of modifications and upgrades, until early March of that year. According to Shuttle Program Manager Ron Dittemore, she was “a leaner, meaner machine,” with more than 1,100 pounds of weight removed and wiring added to support an ISS-specification airlock and external docking adapter. Columbia had also been equipped to support the new Multifunction Electronic Display Subsystem (MEDS) “glass cockpit” to replace her outdated flight deck instrument suite. Despite these improvements, she remained too heavy to haul large ISS components in orbit and was committed at first to just two missions: STS-107 and the STS-109 Hubble Space Telescope servicing flight. The priority of the latter meant that it leapfrogged STS-107 and flew successfully in March 2002. Rick Husband’s mission was tentatively rescheduled for July, some four months later.

Then, in mid-June, with barely five weeks to go, and with Columbia ready to roll over to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) for stacking onto her External Tank and twin Solid Rocket Boosters, a potentially show-stopping problem reared its head. Several cracks—each measuring around 0.09 inches in diameter—had turned up in metal liners, deep within the main engine plumbing of her sister ships, Discovery and Atlantis. Although the cracks did not hold pressure, and thus were not indicative of propellant leaks, it was feared that debris shed from them might work its way into an engine and possibly trigger an explosion. Repair work demanded the removal of Columbia’s three engines and suspended preparations for STS-107 once again. Rick Husband took it in his stride. “We’ve had a fair number of slips through the course of our training,” he told an interviewer in late June, “but we’ve made good use of those. This will be no different.”

With emphasis placed upon the continued construction of the ISS, two other assembly missions—STS-112 and STS-113—flew ahead of Columbia, but by Christmas the STS-107 stack was “hard-down” on Pad 39A, tracking a 16 January 2003 launch. The liner cracks had been repaired, but another crack was found in a 2-inch metal bearing in one of Discovery’s propellant line tie rod assemblies; this prompted another assessment and Columbia was cleared to fly. Like all of the post-9/11 shuttle missions, preparations were undertaken with intense security, with F-15 fighters and Army attack helicopters patrolling the KSC skies. The presence of Israeli Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon on the crew had served to ramp up this security level, with a tottering Middle East peace process and generally unstable political situation giving widespread concern. According to David Saleeba, a former Secret Service operative then working at the Cape as NASA’s head of security, the space agency routinely monitored intelligence reports from the Department of Homeland Security, all of the armed forces, the FBI, Customs, and the FAA. Beach-front hotels occupied by high-ranking Israeli officials were subjected to random car stops and searches by armed officers and bomb-sniffing dogs. The astronauts’ families all had police escorts. The departure times of the crew from Houston and their arrival in Florida were not publicly announced until the last minute, and the precise liftoff time was not revealed until shortly before launch.

“I really don’t enjoy launches,” said Mike Anderson in a NASA interview. “Entries are a little bit better. It’s a little quieter … not quite as violent. You can enjoy it a little bit. For me, on this flight’s entry, I’m just going to sit down in my seat and hopefully reflect on the 16 days on-orbit that we’ve had, anxious to get back to Earth and give the scientists all their research results. I’ll be happy to have the flight behind us.”

The awesome challenge of bringing the crew together was Husband’s responsibility. One of his methods was to take them on a team-building excursion, sponsored by the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), in August 2001. The seven of them backpacked into the mountains of Wyoming with a pair of NOLS instructors and spent nine nights and ten days with 60-pound packs in some of the toughest terrain in the United States. “We got to see some incredible scenery,” recalled Husband. “We got to learn a lot about how each of us deal with the kind of situations that they put us into. It’s also a challenge learning how to keep track of all your equipment, personally, then learning to work together … so that when you come back you know each other’s strengths and weaknesses and so you can maximise that during the rest of your training flow.” The trek took them through dense areas of the Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests—which featured treeless peaks in the 12,000-foot range—and high mountain lakes. Their guides, John Kanengieter and Andy Cline, led the expedition for the first few days, then the seven astronauts took turns to elect a new leader each day and evaluated each other’s performance at nightfall. Despite the serious nature of the expedition, they treated it with aplomb and humor, even telephoning Houston from the 12,990-foot Wind River Peak to inform fellow astronauts that they had landed.

Yet the fact remained that this would be the least-experienced shuttle crew—in terms of space experience, that is—for several years. This made them the butt of several good-natured jokes, several of which they invented themselves. In April 2002, Jerry Ross had flown a record-breaking seventh mission, whereas the experienced members of STS-107 (Husband, Anderson, and Chawla) had barely three missions between them. “Before Jerry Ross flew his seventh mission,” said Husband, “he had six flights to his credit. Our crew had only half that amount of flight experience … but after our flight we’ll have caught up with him and then some!” Added Willie McCool, “He’s got us beat by a factor of two, but when we come back we’ll have ten flights among all of us and we’ll jump ahead of Jerry.”

For Ilan Ramon, it was peculiar to be the first Israeli in space. His mother was a Holocaust survivor from Auschwitz and his father had fought for the independence of Israel. During training, Ramon spoke to many other Holocaust survivors, and when he explained the nature of his mission they could only look at him with astonishment. To them, it was like a dream that they could have never dreamed was possible. The seed of the idea came in December 1995, when U.S. President Bill Clinton and Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres agreed “to proceed with space-based experiments in sustainable water use and environmental protection.” As part of the deal, an Israeli astronaut would operate a multi-spectral camera to investigate the migration of airborne dust from the Sahara Desert and its impact upon global climatic change.

Ramon and the man who would later serve as his backup, Yitzhak May, were selected in April 1997 and began their official training the following year. The Mediterranean Israel Dust Experiment (MEIDEX) was a radiometric camera and wide-field-of-view video camera, mounted on a pallet at the rear of Columbia’s payload bay and capable of operating across six spectral bands, from ultraviolet to infrared. Ramon also packed a pencil drawing, entitled “Moonscape,” by Petr Ginz, a 14-year-old Czeckoslovakian Jew who died at Auschwitz in 1944. Ramon hoped that carrying it into space would symbolize “the winning spirit of this boy.” Although he was a “secular” Jew, Ramon planned to take kosher food into orbit and hoped to observe the three Sabbaths that STS-107 would spend in space. As circumstances transpired, he would be so busy that he could only partly celebrate a single Sabbath.

Partly, that is, because that Sabbath was the final day of the mission, Saturday, 1 February 2003; a day which began with a bright and chirpy Ramon and his crewmates packing away their equipment for re-entry … and a day whose sun went down on one of the darkest days in U.S. and Israeli history.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Your excellent article brings the very real human elements of spaceflight to light. Looking forward to the second part!