SpaceX and United Launch Alliance (ULA) will headline an aggressive campaign of launches by their Falcon 9, Atlas V and Delta IV Heavy fleets in 2021 to deliver a multitude of scientific, military and commercial payloads aloft for a range of customers. Up to three flights of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and two missions by ULA’s Delta IV Heavy are manifested, together with the inaugural test flight of the new Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter and NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) at some stage in the second half of the year.

Additionally, other launch providers in the form of Rocket Lab’s Electron booster, Northrop Grumman Corp.’s Antares and Minotaur vehicles, Astra’s Rocket-3 and Virgin Orbit’s air-launched LauncherOne have an equally ambitious plate of missions scheduled for 2021.

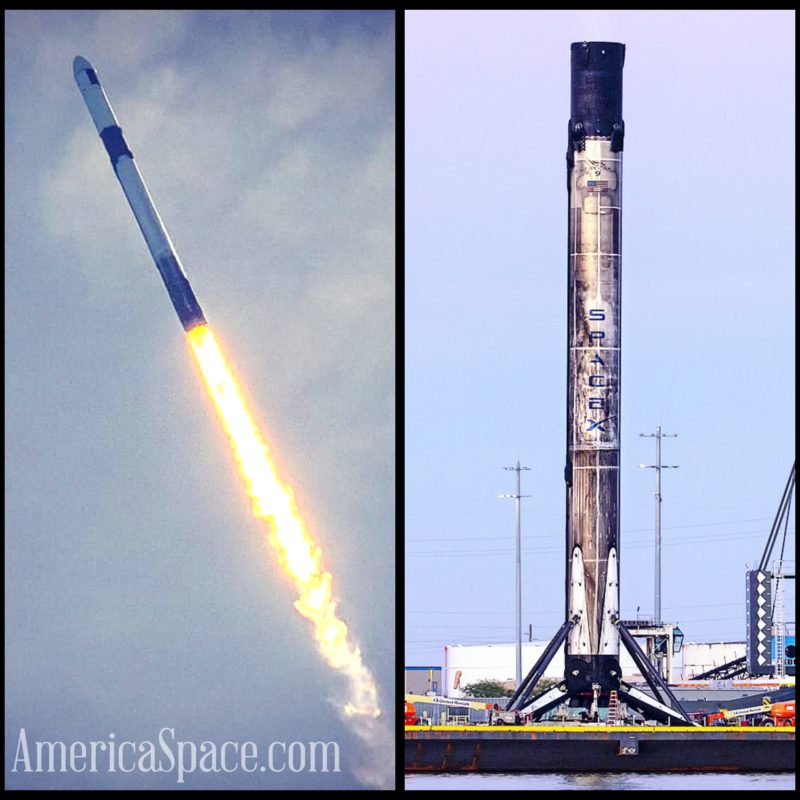

Having executed no fewer than 26 missions in the last dozen months—a personal-best-beating cadence which saw the venerable Falcon 9 establish itself as the United States’ most-flown active operational booster—SpaceX is looking ahead to a busy 2021, with at least an equivalent number of launches slated to take place, including three flights by the colossal, triple-barreled Falcon Heavy.

The first mission of the new year was originally due to fly from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., as soon as Monday, 4 January, with a possibility that SpaceX may repeat its November achievement by flying as many as four times in a single calendar month. The Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship (ASDS), “Just Read the Instructions”, was towed out of Port Canaveral on Wednesday, bound for a recovery location some 410 miles (670 km) offshore in the Atlantic Ocean, to prepare for its first Falcon 9 “catch” of the New Year. However, JRTI and the “Finn Falgout” tug boat later returned to port, indicative of a delay to this schedule.

Several powerful communications satellites are slated to be lifted towards Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO), three cargo-laden Dragons and up to three astronaut-carrying Crew Dragons will visit the International Space Station (ISS) and a pair of Block III Global Positioning System (GPS) navigation and timing satellites will head for Medium Earth Orbit (MEO).

Added to that list, two dedicated U.S. Space Force payloads and two clandestine National Reconnaissance Office payloads are also set to fly in 2021, plus three SmallSat Rideshare Missions, several NASA and commercial science flights and the continued expansion of SpaceX’s already-hundreds-strong network of Starlink low-orbiting internet communications satellites. A total of 833 of the flat-packed Starlinks have been boosted aloft by no fewer than 16 Falcon 9 missions since May 2019.

The payload for what is expected to be the first orbital flight of the year is the 9,900-pound (4,500 kg) Türksat 5A, the first of two new satellites developed and fabricated by Airbus Defence and Space and Turkish Aerospace Industries for Ku-band communications and direct-broadcast television services covering eastern England to western China on behalf of Ankara-based provider, Türksat.

Based upon the all-electric version of Airbus’ EuroStar E3000 satellite “bus”, Türksat-5A will eventually enter a geosynchronous “slot” at 31 degrees East longitude for 15 years of operational service. At some point in the second quarter of 2021, another Falcon 9 will loft the identical Türksat-5B towards a geostationary slot at 42 degrees East. SpaceX received contracts to launch both satellites in November 2017.

And following the successful launch of the SXM-7 high-powered broadcasting satellite for New York-based SiriusXM earlier this month, another Falcon 9 is expected to deliver SXM-8 into orbit at some point in 2021. These heavyweight satellites—each weighing in the order of 15,400 pounds (7,000 kg)—were built by Maxar Technologies, Inc., using the tried-and-true SSL-1300 “bus”, and can provide more than 20 kilowatts of payload power and their large unfurlable S-band antenna reflectors can achieve radio broadcasting without the need for large ground-based dishes. The upcoming SXM-8 satellite will replace the aging XM-4, which has been in orbit since October 2006.

For the first time in almost two years, three Falcon Heavy missions are slated to rise from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. If all three fly as scheduled in 2021, they will bring the total number of missions by this triple-barreled behemoth—currently the most powerful rocket in active operational service, anywhere in the world—to six. The Falcon Heavy carries the potential to lift up to 58,900 pounds (26,700 kg) to geostationary altitude, affording a clear indicator of the size, mass and energy requirements of its payloads.

One of those payloads for 2021 is a large ViaSat-3-class Ka-band communications satellite, built by Boeing and provided by California-headquartered ViaSat, Inc., for worldwide high-capacity broadband provision, whilst the others are dedicated to the U.S. Space Force. One mission, the geostationary-bound USSF-44, was part of a launch contract awarded by the Department of Defense to SpaceX back in February 2019. The other, USSF-52, was awarded to SpaceX in June 2018.

A pair of Block III Global Positioning System (GPS) payloads, also for the Space Force, are expected to be launched next year, bringing the total number of these Medium Earth Orbiting (MEO) positioning, navigation and timing satellites launched atop Falcon 9s since December 2018 to five.

And as part of the same Department of Defense contract which included USSF-44, a pair of highly secretive missions for the National Reconnaissance Office—NROL-85 and NROL-87—will launch from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., and Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., respectively, at some point before December 2021. At least three “rideshare” missions are timetabled for next year, as is Intuitive Machines’ Nova-C and Japan’s Hakuto lunar landers, which represents not only the first launch under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, but is also expected to mark the first attempt by a U.S. private entity to land a spacecraft on the Moon.

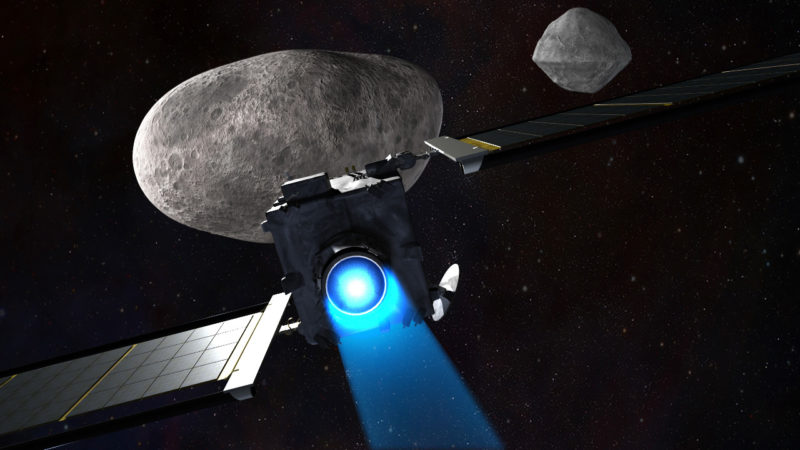

And two major NASA science missions—the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), slated to visit Didymos and evaluate asteroid impact avoidance technologies, and the Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE), whose two-year voyage will explore exotic astronomical phenomena, including black holes, supernova remnants and active galactic nuclei—will fly in July and October, respectively. Added to the list are six ISS-bound missions with crew and cargo, to be outlined in tomorrow’s AmericaSpace feature article.

For United Launch Alliance (ULA), which wrapped up 2020 with six successful missions by its highly reliable Atlas V and Delta IV Heavy fleet, the New Year offers the potential for not only an expanded flight rate, but also the long-awaited maiden voyage of its Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter. With a primary payload of Astrobotic Technology’s 2,800-pound (1,300 kg) Peregrine lunar lander, the mission is due to fly at some point in the second half of 2021, with a healthy list of bookings for future flights, including six ISS-bound missions by Sierra Nevada Corp.’s Dream Chaser cargo ship.

ULA has already trialed much of the tooling and many of the technologies for its new heavylifter on its existing Atlas V fleet, including last November’s NROL-101 flight which was powered by Northrop Grumman Corp.’s uprated GEM-63 strap-on boosters and the recent delivery of the first Out-of-Autoclave (OoA) payload fairing. In early December, a simulated countdown test at Cape Canaveral allowed teams to craft and perfect the timelines for the long-awaited maiden flight.

With ULA’s Delta product-line now in the process of gradual retirement—having already seen the swansong of the Delta II in September 2018 and the final voyage of the “single-stick” Delta IV Medium in August 2019—only the giant, triple-barreled Delta IV Heavy remains, with just four flights sitting on its manifest through the middle of the decade.

Two of those flights are tentatively targeted for 2021, both of which will originate from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-6 at Vandenberg and both of which are dedicated to NRO objectives. Known only as NROL-82 and NROL-91, their exact purposes are shrouded in secrecy, although the Heavy’s lifting potential of 63,470 pounds (28,790 kg) to low-Earth orbit and 31,350 pounds (14,220 kg) to geostationary altitude offer an indicator of their size, mass and energy requirements.

Conversely, the Atlas V fleet retains a more robust launch schedule, with possibly up to nine flights on its books for 2021. The fifth geostationary-orbiting element of the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS GEO-5)—whose fabrication and structural testing was officially completed last month—will ride an Atlas V in July, with the Space Force’s USSF-8 and USSF-12 missions due to launch later in the year. Contracts worth $354.8 million between the Department of Defense and ULA to fly these two Space Force missions were signed in March 2018. Interestingly, USSF-8 will mark the first outing of the “511” variant of the Atlas V, equipped with a 17-foot-diameter (5-meter) payload fairing, a single strap-on solid-fueled booster and a single-engine Centaur upper stage.

The former is believed to be a pair of Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) satellites, while the latter is thought to represent a Wide Field Of View (WFOV) experimental early-warning platform, hosting an Overhead Persistent Infrared (OPIR) sensor. Launch contracts for a third military mission, STP-3 for the Department of Defense’s Space Test Program, were awarded to ULA in June 2017 and it is scheduled to fly on the first Atlas V mission of 2021 in February. Primary payload is STPSat-6, laden with a range of NASA and Air Force investigations.

Other flights include NASA’s Lucy mission, set to launch in October on a multi-year exploration of some of the most enigmatic objects in the known Solar System: the “Trojan” asteroids, gravitationally trapped in alignment with Jupiter’s orbit and which are so ancient that may represent the primordial building-blocks of the planets themselves.

NASA’s Landsat-9 satellite—a follow-on program from the 2013-launched Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LDCM)—will fly in September, after having been delayed by the effects of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, to put its Operational Land Imager (OLI) and Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) instruments to bear on Earth observations and geological survey. And the next Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES-T), scheduled to launch in the December 2021 timeframe, will offer a much-needed new sentinel for timely weather forecasting and meteorological research, following problems experienced in 2018 by its immediate predecessor, GOES-17.

As will be outlined in tomorrow’s AmericaSpace feature, up to six SpaceX missions and potentially two ULA missions are destined to visit the ISS in support of commercial crew and cargo delivery services, together with the maiden uncrewed voyage of NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) and a pair of launches by Northrop Grumman Corp.’s Antares 230+ booster.

Launched from Pad 0A at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) on Wallops Island, Va., the 133-foot-tall (40.3-meter) booster is scheduled to launch the NG-15 and NG-16 Cygnus cargo ships to the station in February and October. Each cargo ship will be laden with an estimated 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) of equipment, payloads and supplies for successive ISS crews. Northrop Grumman also plans to fly its Minuteman/Peacekeeper-derived Minotaur rocket fleet three times—once from SLC-8 at Vandenberg and twice from Pad 0B at MARS—with the two Wallops flights conducted in support of NRO objectives.

Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne, which succumbed to a failure of its NewtonThree first-stage engine shortly after separation from the Boeing 747 “Cosmic Girl” carrier aircraft in May 2020, was scheduled to fly again just before Christmas, although its mission from California’s Mojave Air and Spaceport to deliver ten CubeSats into orbit has met with additional delay. And Astra’s Rocket-3—one of which was destroyed by the Range Safety Officer (RSO) shortly after liftoff in September 2000, whilst a second in December successfully passed the Kármán Line, but suffered upper-stage fuel-mixture problems which precluded the achievement of a stable orbit—may fly as many as three times in 2021.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:ULA Primed for 17 May Launch, First of Eight Atlas V Missions for 2021 « AmericaSpace

Pingback:ULA Primed for 17 May Launch, First of Eight Atlas V Missions for 2021