Virgin Orbit is targeting a two-hour “window” between 6-8 a.m. PDT Wednesday for the second flight of its LauncherOne booster. Designated “Tubular Bells: Part One”, the name honors musician Mike Oldfield’s inaugural album, which Sir Richard Branson produced through his Virgin Records label. The air-launched booster will depart Mojave Air and Space Port in Mojave, Calif., beneath the wing of Virgin Orbit’s modified Boeing 747 carrier aircraft, nicknamed “Cosmic Girl”, laden with seven small satellites for the Department of Defense, the Royal Netherlands Air Force (RNLAF) and Wroclaw, Poland-based SatRevolution. They will be inserted into a circular orbit approximately 310 miles (500 km) above Earth, inclined 60 degrees to the equator.

Preparation for this mission has been exceptionally smooth (and fast), with contracts to launch the RNLAF and SatRevolution birds formally signed since LauncherOne’s most recent mission on 17 January. The 70-foot-long (21-meter) LauncherOne vehicle was declared fully integrated and ready for shipment in early May and by the beginning of June had arrived at the Mojave test site and was mated to Cosmic Girl’s port-side wing.

This set the stage for an extensive test phase, which included loading liquid oxygen aboard the booster and fully pressurizing its cryogenic system to flight levels. “During this test, we were able to achieve all of our planned objectives,” noted Virgin Orbit, “including 100-percent liquid oxygen and fuel fill and normal pressurization of all high-pressure gas systems with no tank leakage.”

Following the completion of “wet” dress rehearsal testing last week, Virgin Orbit announced that it was targeting late June to early July for Tubular Bells: Part One, before revealing on Monday that it was shooting for a two-hour “launch window” between 6-8 a.m. PDT Wednesday. “Hardware is all in excellent shape,” it tweeted, “and we’re ready to step through our pre-launch procedures.”

Only days after its triumphant January flight, Virgin Orbit contracted with the Royal Netherlands Air Force (RNLAF) to deliver the first Dutch military satellite—a tiny CubeSat named BRIK-II—into orbit for navigation, communications and Earth observations. Technologies aboard the small spacecraft are thought to include a military radio frequency receiver, an Ultra-High-Frequency (UHF) communications system and a Langmuir probe to measure electron densities in the atmosphere.

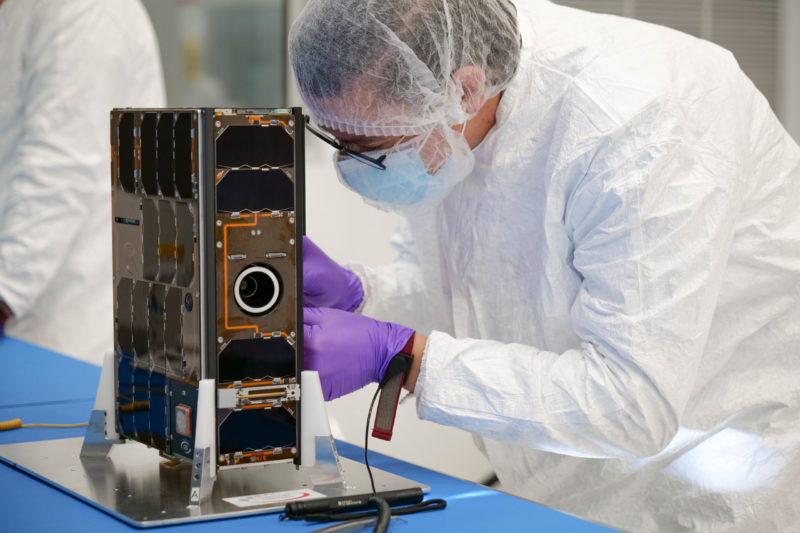

Design and fabrication of BRIK-II, which takes the form of a “6U” CubeSat, with approximate dimensions of 60 x 10 x 10 cm (23.6 x 3.9 x 3.9 inches), got underway back in November 2017, with an expectation that it would “provide a meaningful contribution to military operations”. The name “brik” comes from the Van Meel Brikken biplane, first flown more than a century ago, which was the first Dutch military aircraft.

“Being able to launch our very first satellite is a major milestone for the RNLAF and the Dutch joint force as a whole,” said Lt. Gen. Dennis Luyt, RNLAF commanding officer, speaking in January. The historic sentiment was echoed by Virgin Orbit CEO Dan Hart. “We’re looking forward to seeing the Netherlands and the U.S. find mutual benefit from leveraging our uniquely flexible and mobile launch system,” added Mr. Hart. “I can already foresee the day when we will take off from a runway on Dutch soil and deliver RNLAF satellites to space directly.”

But not just yet, for Wednesday’s long-awaited LauncherOne—like its predecessor in January—will originate from the 4.7-square-mile (12.1-square-kilometer) Mojave Air and Space Port in Mojave, Calif., the first facility ever licensed in the United States for horizontal launches of reusable space vehicles.

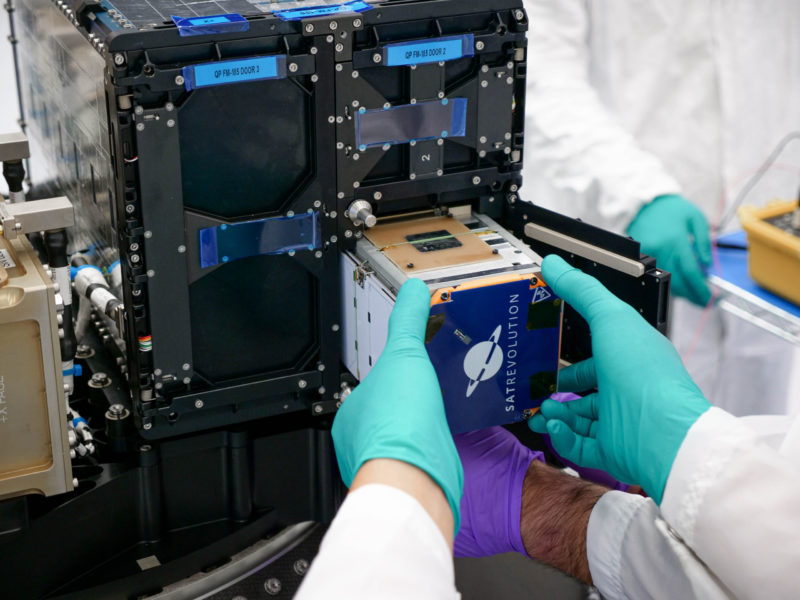

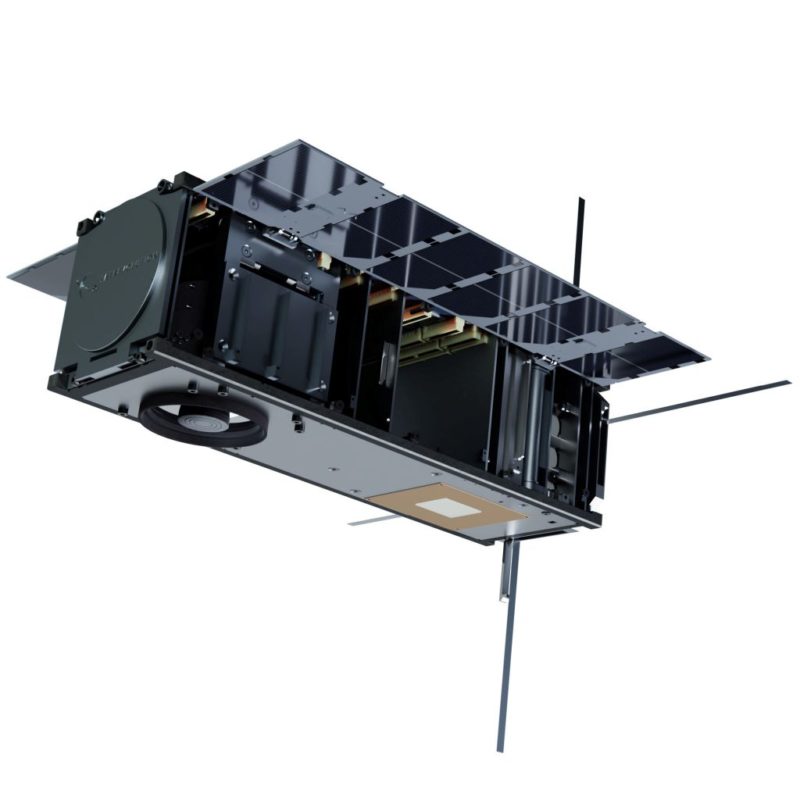

Just last February, Virgin Orbit inked a separate deal with Wroclaw, Poland-headquartered SatRevolution to lift a pair of small satellites known as STORK-4 and STORK-5 (MARTA). These form the first two members of an eventual 14-satellite constellation, which, when fully operational, will gather multispectral medium-resolution imagery and data for customers spanning the agricultural and energy sectors in Poland, the United States and elsewhere. Formally unveiled by SatRevolution last summer, both satellites are believed to include the firm’s Vision-3000 imaging system, which has a ground resolution as fine as 16.4 feet (5 meters).

The STORK dual-satellite mission also features “a reduced-timeline integration” process, part of efforts to demonstrate “a responsive launch service” and trial the oft-touted rapid call-up capabilities for the LauncherOne system.

As for the final payload, STP-27VPA has been developed by the Department of Defense Space Test Program (STP) and is believed to number up to four small technology demonstration satellites. In November 2017, plans for “a prototype flight” with LauncherOne were announced, with original hopes of flying as soon as January 2019. However, that plan was based upon a projected maiden voyage of the air-launched booster in mid-2018, which ultimately did not come to pass.

LauncherOne’s maiden voyage finally took place in May 2020, and hopes soared that Virgin Orbit’s sweet little bird would become only the second operational Air Launch to Orbit (ALTO) system, after Northrop Grumman Corp.’s long-serving Pegasus winged booster. Powered by a mixture of liquid oxygen and a highly refined form of rocket-grade kerosene (known as “RP-1”), LauncherOne was expected to burn its NewtonThree first-stage engine—with a propulsive yield of 73,500 pounds (33,340 kg)—for about three minutes. But despite a successful release from under Cosmic Girl’s wing, a malfunction caused the engine to extinguish itself and LauncherOne plunged into the Pacific Ocean.

It subsequently became clear that a breach in the high-pressure propellant line responsible for carrying liquid oxygen to the first stage’s combustion chamber had precipitated this loss of thrust. This effectively stymied the flow of oxidizer to the NewtonThree engine. And in spite of the steady worldwide march of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, Virgin Orbit engineers probed diligently through last summer to identify a forward path with an eye on their next launch. “We’ve put our hardware through a punishing barrage of tests to shake out any hidden surprises that might otherwise doom us to repeat the mishap,” it was noted in an August update.

Virgin Orbit adopted what it described as a “belt-and-suspenders” approach to the failure: “fixing the obvious issues we observed and also proactively addressing issues we didn’t observe but fall into the realm of possible contributors”. Specifically, this approach resulted in strengthening of parts of the high-pressure liquid oxygen feed system and an increase in operating margins to maximize robustness and reliability.

Last October, Virgin Orbit announced its intent to push ahead with a second LauncherOne mission—dubbed “Launch Demo-2”—before year’s end, with the hardware having already been shipped to Mojave Air and Space Port in late August. But as with so many best-laid plans of 2020, the launch slipped slowly but surely into the opening weeks of the New Year. Finally, on 17 January LauncherOne roared perfectly aloft and deployed nine CubeSats for NASA experimenters and eight academic institutions spanning the United States from Tennessee to California, from Florida to Colorado and from Maryland to Utah.

Following this spectacular success, plans were already well-laid for the second mission. Early Wednesday, Cosmic Girl will fly about an hour out to sea then enter a loop—known as the “racetrack”—to await the “Go/No-Go” polls. After these are done, Cosmic Girl’s flight crew will press into their final checks, before heading into the Terminal Countdown Autosequence. And when that step is reached, LauncherOne’s computerized brain will assume command of the system before release and engine ignition.

The NewtonThree engine should burn for a little over three minutes, before separating, after which the NewtonFour engine of the second stage will pick up the baton for about another four minutes. During its burn, LauncherOne’s payload fairing will be discarded, exposing the payloads to the vacuum of space, ahead of deployment.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » Commercial Space »