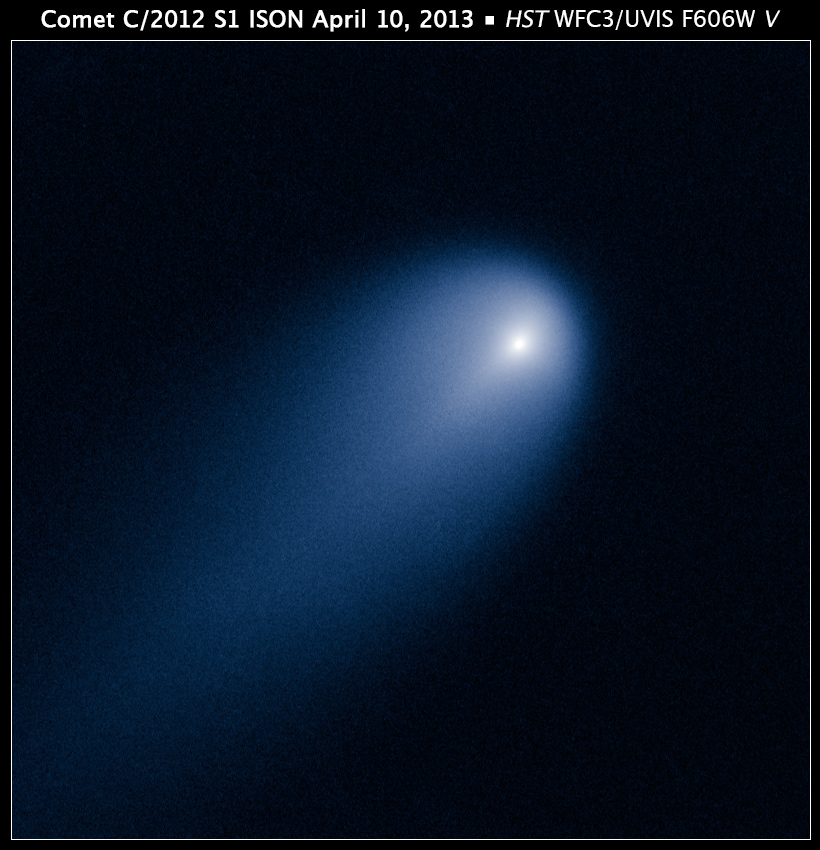

Coming soon to a region of space near you: comet ISON, which is expected to put on a spectacular show toward the end of the year. Currently, ISON is about 258 million miles from the Sun, between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars. Its tail already stretches out more than three-quarters of the distance from the Earth to the Moon and is being keenly watched by astronomers. NASA scientists have now reported that, using the Spitzer Space Telescope, they’ve detected carbon dioxide in the tail.

Comet ISON, also known as C/2012 S1, was discovered on September 21 last year by Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok at the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) based near Kislovodsk, Russia. It’s believed to be making its first trip to the inner solar system from the Oort Cloud—a vast, roughly spherical storehouse of trillions of frozen cometary nuclei—that lies more than a tenth of a light-year from the Sun. By studying this pristine relic, dating back some 4.5 billion years, researchers hope to learn more about the make-up of the cloud of gas and dust from which the Sun and planets formed.

“These fabulous observations of ISON are unique and set the stage for more observations and discoveries to follow as part of a comprehensive NASA campaign to observe the comet,” said James L. Green, NASA’s director of planetary science. “ISON is very exciting. We believe that data collected from this comet can help explain how and when the solar system first formed.”

As a comet draws nearer to the Sun, it steadily warms up, causing its volatile components to evaporate into space. One of the first gases to begin vaporizing is carbon dioxide, which can start to escape when the comet is as far away as Saturn. Observations by Spitzer’s Infrared Array Camera, back in mid-June, showed that ISON had already started fizzing CO2 in a manner that puts it in a category known as “soda-pop comets.” Each day the approaching comet is losing about 2.2 million pounds of the gas, along with a healthy 120 million pounds of dust—a sizeable amount for object that, at less than 3 miles across, is only the size of a small mountain.

“This observation gives us a good picture of part of the composition of ISON and, by extension, of the proto-planetary disk from which the planets were formed,” said Carey Lisse, leader of NASA’s Comet ISON Observation Campaign and a senior research scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. “Much of the carbon in the comet appears to be locked up in carbon dioxide ice. We will know even more in late July and August, when the comet begins to warm up near the water-ice line outside of the orbit of Mars, and we can detect the most abundant frozen gas, which is water, as it boils away from the comet.”

As ISON gets closer, astronomers hope to learn far more about this first-time visitor. Soon other substances, including water vapor, will begin pouring out, revealing their presence in the spectrum of light from the comet to instruments on the ground and those, like Spitzer, in space. During September, ISON should become visible through binoculars and, after that, to the unaided eye as its head for perihelion—its closest approach to the Sun (at a distance of just 724,000 miles) on November 28.

“We estimate ISON is emitting about 2.2 million pounds (1 million kilograms) of what is most likely carbon dioxide gas and about 120 million pounds (54.4 million kilograms) of dust every day,” Lisse said. “Previous observations made by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission and Deep Impact spacecraft gave us only upper limits for any gas emission from ISON. Thanks to Spitzer, we now know for sure the comet’s distant activity has been powered by gas.”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” Retro Space Images & AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace