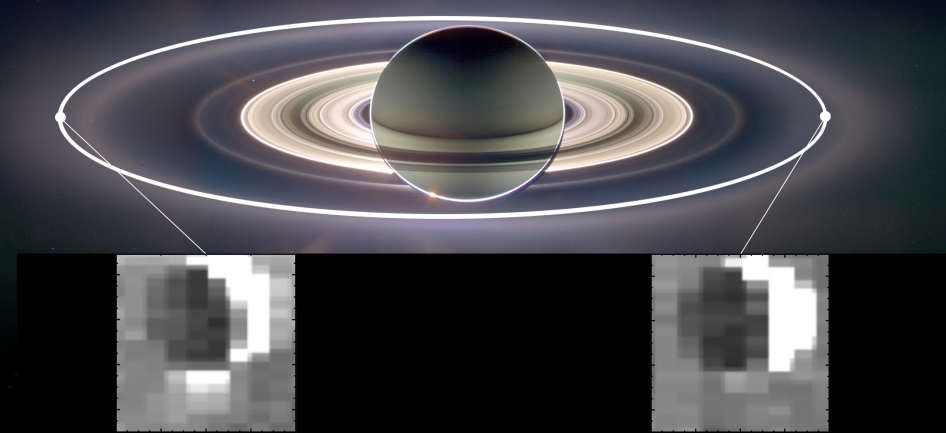

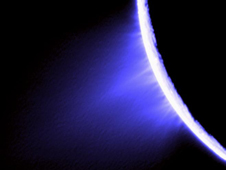

Saturn’s 314-mile-wide icy moon Enceladus has been teasing astronomers ever since they found that it shoots huge jets of water ice and other material into space from its south polar region. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft first spotted the plumes, gushing out of fissures dubbed “tiger stripes,” in 2005. Now, observations by the spacecraft have shown that the amount of ice and salty chemicals spewed out varies with the moon’s distance from the planet. The discovery forms the subject of a paper in this week’s

edition of the journal Nature.

“The jets of Enceladus apparently work like adjustable garden hose nozzles,” explained Matt Hedman, lead author of the paper and a member of the Cassini science team. “The nozzles are almost closed when Enceladus is closer to Saturn and are most open when the moon is farthest away. We think this has to do with how Saturn squeezes and releases the moon with its gravity.”

Planetary astronomers had theorized that the strength of the jets probably changed as Enceladus tracked around its orbit but had no data to confirm this. The new study draws on measurements collected by Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIMS) between 2005 and 2012, which showed that the brightness of the plumes was up to four times greater when the moon was farthest from Saturn than when it was at the point of nearest separation.

The pattern of brightening as the moon moved away from the great ringed planet, taken together with models of how Saturn’s gravity affects Enceladus, helped the authors of the new paper formulate a theory as to what was going on. Close up, Saturn’s squeezing partly closes up the south polar fissures, limiting how much material they can release. When moon and planet are farther apart, the fissures are allowed to open wider and give out bigger, brighter plumes.

The finding boosts the changes that an underground ocean may exist on Enceladus. “The way the jets react so responsively to changing stresses on Enceladus suggests they have their origins in a large body of liquid water,” said Christophe Sotin, a co-author of the paper, who is also on the Cassini team. If a subsurface watery ocean does exist on Enceladus, this also opens up the prospect that there may be life, or at least complex organic chemistry, on this small, far-away body.

“The way the jets react so responsively to changing stresses on Enceladus suggests they have their origins in a large body of liquid water,” said Christophe Sotin, a co-author and Cassini team member at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. “Liquid water was key to the development of life on Earth, so these discoveries whet the appetite to know whether life exists everywhere water is present.”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” Retro Space Images & AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace