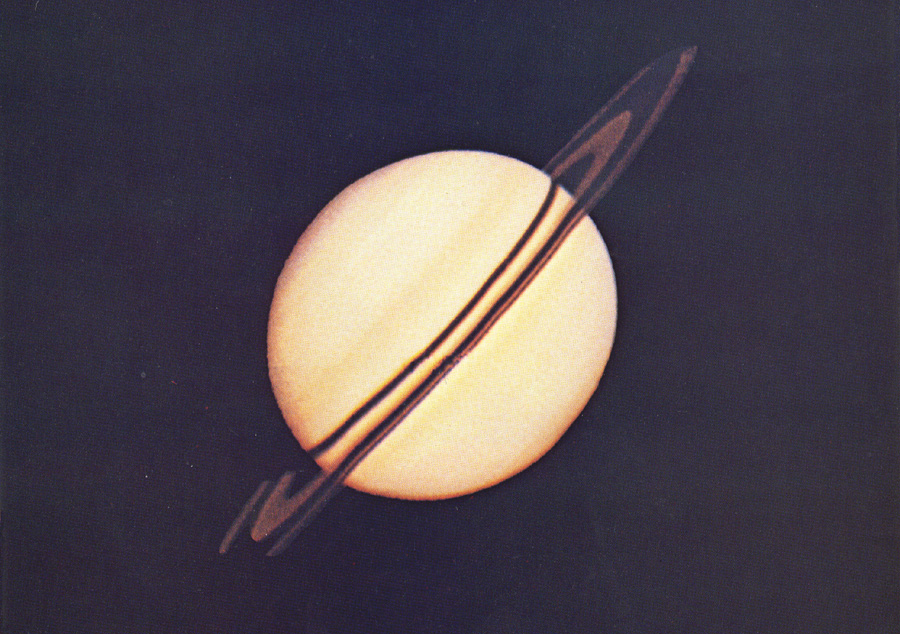

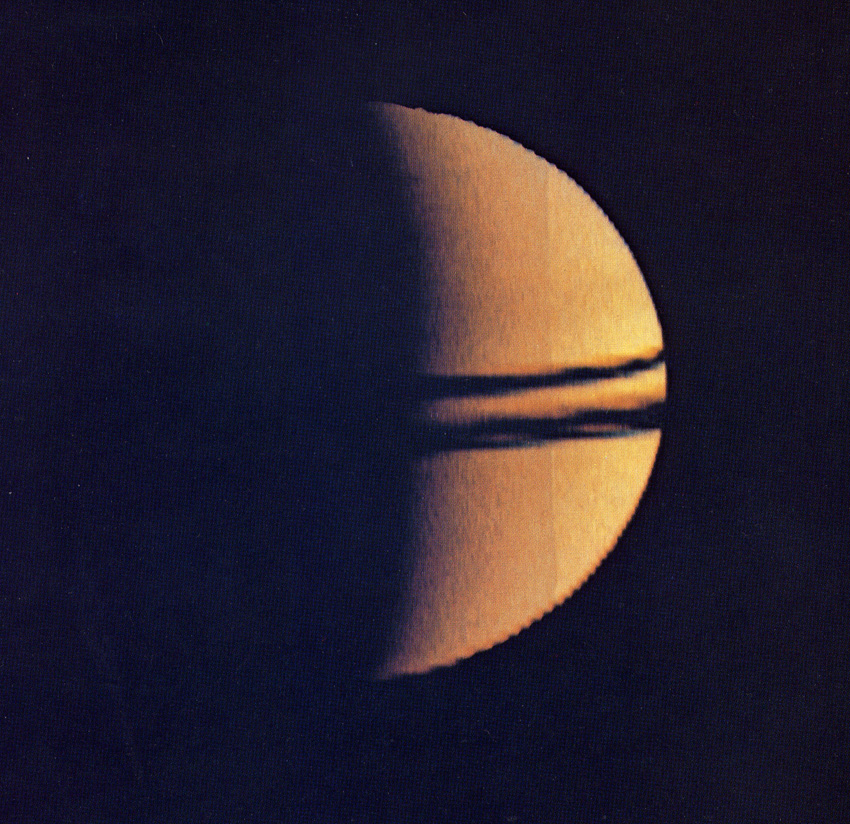

Spectacular Saturn—the Solar System’s second-largest planet—has been known to humanity for millennia, although only in the last few centuries since the invention of the telescope has its nature and its glorious system of rings entered popular consciousness and become better understood. Today, of course, following the visitations of the Voyager probes and more recently the multi-year tour by the joint U.S./European Cassini mission, we know more about Saturn than ever before. Yet 40 years ago today, on 1 September 1979, human eyes glimpsed the planetary “Bringer of Old Age” close-up and in mesmerizing detail for the first time, all thanks to a spacecraft which was intended as a backup to another.

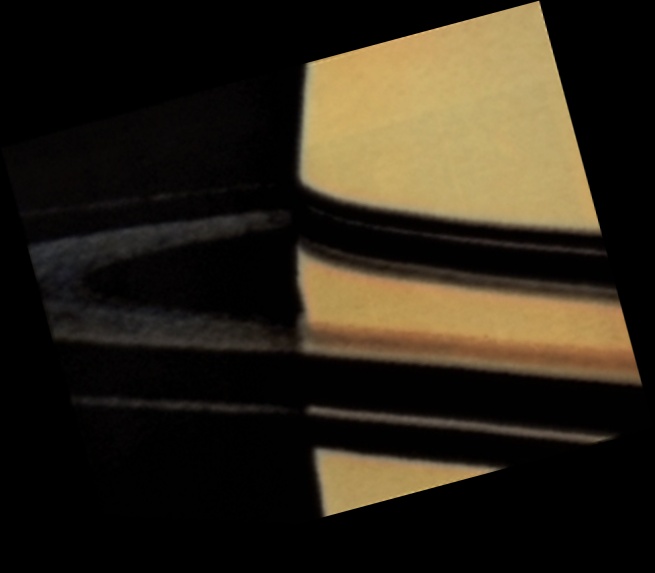

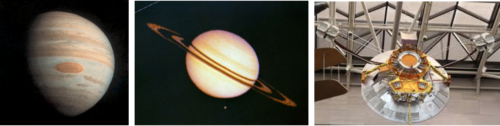

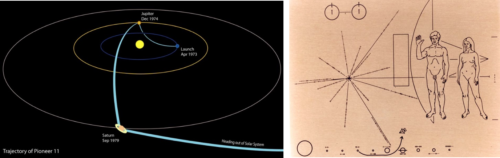

Launched in April 1973, Pioneer 11 was one of two probes specifically intended to conduct the first exploration of the outer Solar System. The 570-pound (260 kg) spacecraft and its twin, Pioneer 10, were targeted to characterize for the first time the interplanetary medium beyond the orbit of Mars, together with the first in-situ examination of the asteroid belt and detailed observations of giant Jupiter. However, it was hoped that if Pioneer 10 succeeded in these daunting objectives, Pioneer 11’s trajectory could be tweaked to enable humanity’s first-ever, close-range inspection of Saturn in September 1979. Key goals of a Saturn rendezvous included mapping its immense magnetic field, measuring its interaction with the solar wind, taking temperature and pressure profiles of its atmosphere, observing its unique ring system and pegging the mass and other characteristics of the planet and its retinue of moons. Another fundamental facet Pioneer 11’s visit to Saturn was to verify the environment of the ring plane, and how safely it could be traversed by a spacecraft, ahead of the more advanced Voyager 1 and 2 missions.

For its part, Pioneer 10 rose from Earth in March 1972 and successfully crossed the orbit of Mars, passed through the mysterious regime of the asteroid belt without incident by February 1973 and achieved a triumphant rendezvous with Jupiter in December 1973. By this time, Pioneer 11 itself had also been launched. Following a spate of poor weather in Florida which hampered pre-flight preparations, its Atlas-Centaur booster roared away from Launch Complex (LC)-36 at Cape Canaveral at 9:11 p.m. EDT on 5 April 1973 and delivered the tiny spacecraft smoothly aloft. Fifteen minutes after departing Earth forever, Pioneer 11 separated from the final stage of the launch vehicle, but all was not well.

In fact, its first hours of flight proved somewhat traumatic, when one of the two booms holding its four Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs)—plutonium-fed power sources which yielded 155 watts at launch and were expected to have naturally decayed to 140 watts by the time it reached Jupiter—stubbornly refused to fully unfurl. The booms were designed to position the nuclear powerplants as far away from the scientific payload on the main body of the spacecraft as possible, as well as helping to slow Pioneer 11’s initial spin-rate. Several “burns” by the hydrazine thrusters were executed in an effort to vibrate it open and the spacecraft was reoriented to prevent excessive solar heating, after which the stubborn boom successfully unfurled. This served to bring Pioneer 11’s spin rate within its predicted parameters at 4.8 rpm.

Five days after launch, trajectory specialists slightly nudged its course to aim its passage just to the “right” of Jupiter, as seen from Earth, some 12,400 miles (20,000 km) above the cloud-tops, in order to open up an array of options, including the possibility of a subsequent Saturn flyby. By this stage, all 12 scientific instruments were functioning normally and returning valuable data.

By March 1974, Pioneer 11 had smoothly traversed the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, revealing—as did its twin, Pioneer 10—an apparent absence of high-velocity projectiles which might penetrate and cripple future spacecraft. In fact, most of the larger asteroidal particles turned out to range between 0.004 inches (0.1 mm) to 0.04 inches (1 mm), with only a few sizing larger than 4-8 inches (10-20 cm) across. A month later, in April, the spacecraft’s trajectory was again nudged to correct its Jupiter aim-point and approach the giant planet three times closer than Pioneer 10. As well as providing improved data, it would also utilize the giant’s immense gravity to accelerate to 108,000 mph (173,000 km/h) to reach Saturn, more than 1.5 billion miles (2.4 billion km) away.

Early in December 1974, after 21 months traveling through deep space, Pioneer 11 became the second spacecraft in history to successfully reach and study Jupiter. Its next mission would truly be an adventure into the Solar System’s uncharted depths. And with the unknown came problems. They manifested themselves in the form of spurious spacecraft commands, which went on for several months and could not be attributed to radiation. It turned out that Pioneer 11’s asteroid/meteoroid detector—a non-imaging tool designed to track particles from dust-size up to larger objects—had sustained radiation damage and was the source of the problem. It was correspondingly shut down, but during the process to identify the problem the spacecraft’s healthy plasma analyzer was also turned off. When commanded back on again, it came alive, but for a while refused to provide data. It was just another reminder that Pioneer 11 was voyaging into the unknown.

There existed two main proposals to observe Saturn at close range, which called for Pioneer 11 to daringly pass inside the ring-plane or, more conservatively, outside. NASA management opted for the more conservative option, keenly aware that Pioneer’s data would prove critically important for the upcoming Voyager missions.

Humanity’s first-ever visit to Saturn would clearly be a momentous event, especially for those retirees who had worked on the project earlier in its conception. Six key retirees, known affectionately as the “over-the-hill gang”, returned to work for this critical period.

Late in July 1979, the spacecraft’s campaign to observe Saturn from afar began in earnest. NASA managers had selected a flight path which would provide a pathfinder for the twin Voyager probes—which, it was hoped, would conduct flybys of all four gas giants during their “Grand Tour” of the outer Solar System—and on 29 August Pioneer 11 began several weeks of close-range observations of the Saturnian system. Early that morning, it passed the strange, two-toned moon Iapetus, followed by tiny Phoebe a few hours later. Two days later, the spacecraft swept within 414,000 miles (666,000 km) of Hyperion, before embarking on its close passage of Saturn on 1 September.

That day’s events commenced with encounters with the moons Epimetheus, Atlas, Mimas—characterized by its vast Herschel crater—and Dione, before achieving a closest approach to Saturn of 12,795 miles (20,591 km) at 11:29:34 a.m. EDT. Over the next few hours, Pioneer 11 passed the moons Janus, Tethys, Enceladus, Calypson and Rhea, before making a distant flyby of Saturn’s giant, planet-sized satellite Titan at 1 p.m. EDT on 2 September. Yet even those distant observations showed that smog-enshrouded Titan was likely far too cold to support life.

Several more weeks of distant observations were conducted from afar and by the beginning of October 1979 Pioneer 11’s focus on Saturn ended, as the ringed planet diminished and size and steadily disappeared from view. So began the Pioneer Interstellar Mission to send the spacecraft out of the Solar System forever.

And that voyage was a long one. Not until February 1990—more than a decade after its triumphant Saturn flyby—did Pioneer 11 cross the orbit of the outermost planet, Neptune, and commence its interstellar mission. Five years later, the remaining power levels aboard the spacecraft had grown so low that its scientific instruments could no longer be operated adequately and all contact came to an end. In the fall of 1995, more than two decades had passed since launch and Pioneer 11 was four billion miles (6.4 billion km) from its planet-of-origin and its radio signal took over six hours to complete the one-way transit back to Earth.

“Americans should remember Pioneer 11 as a great achievement,” said then-NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin. “This is the little spacecraft that could, a venerable explorer that has taught us a great deal about the Solar System and, in the end, about our own innate drive to learn. Pioneer 11 is what NASA is all about: exploration beyond the frontier.”

Its mapping of Jupiter’s radiation environment had paved the way for the Voyagers and it had journeyed way above the ecliptic plane—as high as 100 million miles (160 million km), in fact—to reveal in tantalizing depth the nature of the Sun’s magnetic field of influence. During the historic Saturn encounter, 40 years ago this weekend, it had examined the magnetosphere, magnetic field and general structure of the second-biggest planet in the Solar System. It had found a new ring, labeled the “F” ring, which resembled a contorted tangle of narrow strands, its material possibly “shepherded” into place by unseen moonlets. This was subsequently proven in 1980 when Voyager 1 identified the tiny moons Prometheus and Pandora at the F ring’s edge. Pioneer 11 showed that Saturn’s magnetic field was slightly tiled by less than a degree to its rotation poles and revealed the presence of a magnetospheric “bow shock” extending 870,000 miles (1.4 million km) from its center.

Today, nearly five decades since launch and almost a quarter-century since it fell silent, Pioneer 11 resides more than 100 Astronomical Units—well in excess of 9.3 billion miles (15 billion km)—from Earth and is steadily moving outward at about 25,150 mph (40,470 km/h). Its future and what its long-deaf sensors and long-blind imaging instruments may someday encounter can only be guessed at. Yet one thing remains certain. Forty years on from its spectacular, whistlestop tour of Saturn, Pioneer 11’s name is more apt than ever, for it was truly a pioneer for all of our subsequent visits to Saturn and its findings have substantially aided the development of future missions to explore this strange giant planet.