Nine years ago NASA launched a spacecraft to do something that had never been done at any point in recorded history: to visit a comet and punch a hole in its face to investigate the surface and interior composition of one of nature’s most legendary heavenly bodies. The Deep Impact mission was not only a success, but went on after fulfilling its primary mission to visit a second comet, and continued on even further to show us worlds in other star systems throughout the galaxy. Today, however, NASA announced that, after a month of failed troubleshooting to communicate with the spacecraft, Deep Impact is on her own.

“Despite this unexpected final curtain call, Deep Impact already achieved much more than ever was envisioned,” said Lindley Johnson, the Discovery Program Executive at NASA Headquarters and the Program Executive for the mission since a year before it launched. “Deep Impact has completely overturned what we thought we knew about comets and also provided a treasure trove of additional planetary science that will be the source data of research for years to come.”

The mission team lost contact with Deep Impact on Aug. 8, and repeated uplink commands to reactivate the spacecraft’s onboard systems have failed. With no control, Deep Impact’s orientation is at the mercy of its space environment. Without its radio antenna positioned correctly, it cannot communicate with Earth, and without its solar arrays positioned properly, it cannot power itself, which allows the cold of space to ruin onboard equipment, freezing batteries and propulsion systems. The exact cause of the failure is not known, but NASA’s analysis has revealed potential problems with computer time tagging, which could have led to loss of control for Deep Impact’s orientation.

“Deep Impact has been a fantastic, long-lasting spacecraft that has produced far more data than we had planned,” said Mike A’Hearn, the Deep Impact principal investigator at the University of Maryland in College Park. “It has revolutionized our understanding of comets and their activity.”

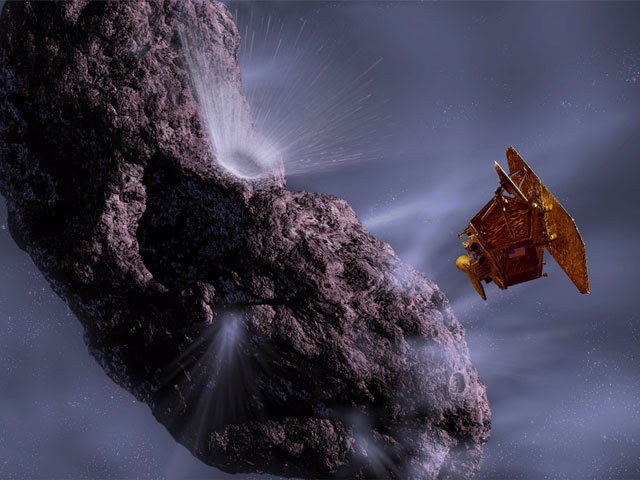

Launched in January 2005 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, Deep Impact traveled almost 270 million miles to meet with comet Temple-1. Upon its arrival six months later, the spacecraft fired an 815-pound copper impactor and smashed a hole into the face of Temple-1, in what was arguably one of the most epic July 4th fireworks shows ever, exposing the comet’s guts and providing mankind with data and views never seen before. The impactor worked flawlessly, and a camera onboard sent hi-res images of its suicidal dive up until 3.7 seconds before impact. Explosives were too expensive and NASA was fairly confident that copper was not present on Temple-1, so in an effort to reduce debris from the impactor interfering with scientific measurements they used a copper payload.

Two weeks later, with a healthy spacecraft and plenty of fuel left, NASA decided to extend Deep Impact’s mission to investigate another comet—Hartley 2. The spacecraft was brought back toward Earth, using our planet’s gravity to assist in a “push” towards Hartley 2. Deep Impact came within 431 miles of the comet on Nov. 4, 2010, using its two telescopes and an infrared spectrometer to make observations which proved Hartley 2 was powered by dry ice, rather than water vapor which was the previous theory.

Not only was Deep Impact a comet-chasing explorer for mankind, the spacecraft was also utilized as a planetary observatory, capturing some 500,000 images of various heavenly bodies across the universe. Deep Impact’s Extrasolar Planet Observation and Characterization (EPOCh) mission aimed to study the physical properties of giant planets in other star systems already discovered and search for rings, moons, and planets as small as three Earth masses. Planetary systems in star constellations such as Leo, Draco, Lyra, and Cygnus were observed. The spacecraft even pointed its most powerful telescope to the constellation Hercules, providing valuable data on planet TReS-3 some 1,300 light-years away.

Now, after close to five billion miles traveled, one of NASA’s most unique and successful missions to date has come to an end.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One of many now “silent messengers” of humanity traveling through the Universe! Fate unknown but what an eternal legacy we leave behind.