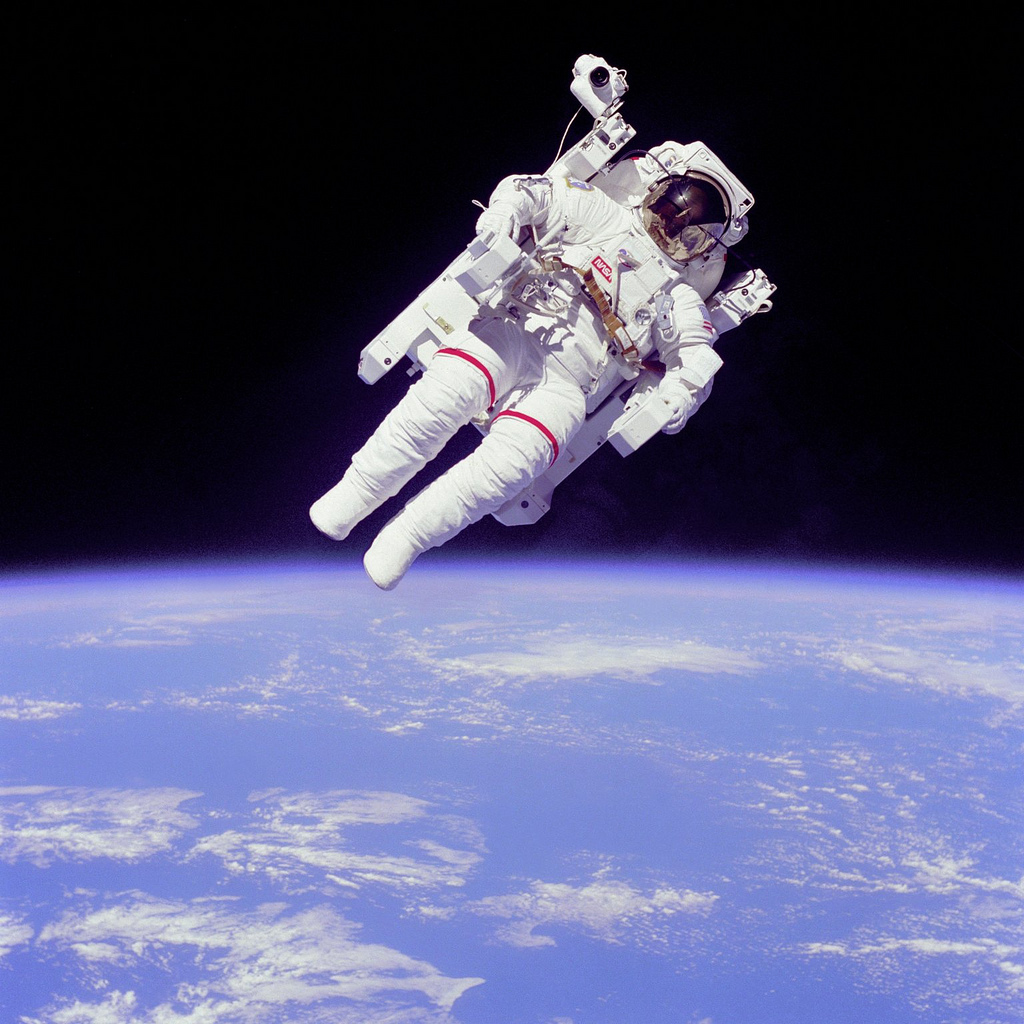

Thirty years ago this week, in February 1984, NASA launched its 10th shuttle mission, with a five-man crew and a relatively “vanilla” pair of commercial communications satellites to be deployed from Challenger. However, that was where the “ordinary” nature of Mission 41B—the first flight to be officially redesignated with a somewhat clumsy nomenclature of letters and numbers—ended, for in pride of place on the crew’s patch was a jet-propelled space suit backpack, known as the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU). It would be flown by astronauts Bruce McCandless and Bob Stewart, during which time they would become the first “untethered” spacewalkers in history. And McCandless’ foray would yield one of the most famous space photographs ever taken; a photograph which ended up on the covers of National Geographic and Aviation Week and which, even 30 years later, still retains pride of place on many desktop wallpapers, screensavers, and pieces of wall art. It even sparked a bizarre copyright case involving the singer Dido.

For McCandless, who joined NASA in April 1966, alongside Mission 41B’s commander Vance Brand, this momentous voyage into space would mark the end of a long wait. One of the reasons for his lengthy status as an astronaut-in-waiting was that he had been instrumental in the design and development of the MMU and had long been tapped to test it on its first outing in space. “In retrospect,” he told this author in an email correspondence in March 2006, “I probably lavished too much attention on scientific and engineering interests, as opposed to the flying, flying and more flying.”

It is often said that great men come from great families with great and illustrious backgrounds, and McCandless, born in Boston, Mass., on 8 June 1937, certainly fulfilled much of this criteria. His great-great-grandfather, David Colbert McCanles, was a Nebraska rancher, a former sheriff, and, as a member of the “McCanles Gang,” was infamously killed by “Wild Bill” Hickok in December 1861. The family subsequently changed their name to “McCandless” and moved to Colorado. McCanles’ grandson, Byron McCandless, rose to become a Navy commodore who helped to create two separate designs for the Flag of the President of the United States. His son, the “first” Bruce McCandless, also followed a military career and graduated from the Naval Academy, but made his name and reputation during a bloody naval battle off Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

In the early hours of 13 November 1942, Lieutenant-Commander Bruce McCandless was serving as communications officer aboard the U.S.S. San Francisco when the ship’s navigation bridge sustained a direct hit from the Japanese cruiser Nagara. The incident killed the admiral, his captain, and most of the other senior officers. McCandless himself was rendered unconscious and, upon reviving, he and another lieutenant-commander, Herbert Schonland, took command. Steering and control of the San Francisco were lost and regained on several occasions, and the ship endured 45 direct hits and sustained major structural damage, yet survived to fight another day. McCandless and Schonland both received the Congressional Medal of Honor, with citations which praised their heroism, leadership, and bravery. Both continued their naval careers and both retired as rear-admirals; McCandless would die in 1968, two years after NASA selected his son as an astronaut. Both Byron and the first Bruce McCandless would have streets at naval bases named in their honor, as well as a frigate, the U.S.S. McCandless, launched in 1971.

Bruce McCandless II was barely 5 years old when his father fought through the night to save himself and his shipmates in November 1942, but a naval career beckoned and a parent with a Medal of Honor virtually guaranteed him an appointment to a prestigious military academy. McCandless completed high school in Long Beach, Calif., and entered the Naval Academy, receiving his degree in 1958 and graduating second in his class of 899 students. (One of his contemporaries was John McCain, later a senator and Barack Obama’s Republican opponent in the 2008 presidential election.) At NASA, McCandless first entered the headlines in July 1969 as the Capcom in Mission Control when Neil Armstrong first set foot on the Moon.

McCandless was later assigned as backup pilot for the first Skylab mission and participated in the development of an astronaut maneuvering unit known as Experiment M-509. This nitrogen-fed backpack was tested inside the space station in 1973 and served as a forerunner of the MMU. In fact, the spectacular success of the MMU would win NASA and prime contractor Martin Marietta the Collier Trophy for 1984. McCandless, together with NASA’s Charles “Ed” Whitsett and Martin Marietta’s Walter “Bill” Bollendonk, were recognized for their contributions to its development and checkout. Whitsett in particular would pay tribute to McCandless: “Nobody has left his stamp on any instrument in space,” he told the Washington Post, “like Bruce has left his mark on the backpack.”

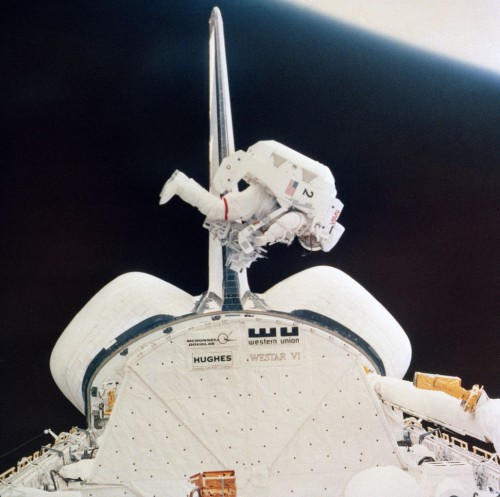

One of the MMU’s original aims was to enable spacewalkers to inspect and perhaps repair damaged thermal protection materials on the shuttle’s wings and lower surfaces. However, it had been hampered for some years by management apathy and lack of firm funding. That changed in early 1979, as Columbia was being moved from California to Florida. During the move, several heat-resistant tiles were lost from her airframe and renewed vigor was injected into developing the MMU. By the time STS-1 took to the skies in April 1981, most of the tile problems, seemingly, had been solved and no MMU was aboard. It would instead be used, said NASA, for satellite repairs and maintenance, and its usefulness was enhanced by the provision of electrical sockets for tools, portable lights, and cameras.

The MMU measured 4 feet (1.2 meters) high, 2.6 feet (81 cm) wide, and 2.1 feet (66 cm) deep. According to astronaut Joe Allen, who flew it in November 1984, it resembled “some kind of overstuffed rocket chair.” On a typical mission, two MMUs were stored on Flight Support Structures (FSS) on opposing walls of the shuttle’s payload bay. An astronaut would back into it and secure two spring-loaded latches and a lap belt into place, then release the MMU from its support structure and float free.

After more than four years in the design definition stage, in February 1980 NASA awarded the $26.7 million MMU fabrication contract to Martin Marietta of Denver, Colo. The first two operational flight units, valued at around $10 million apiece, arrived at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, in September 1983, to support astronaut training. Two months later, they were installed aboard Challenger. Each weighing 308 pounds (140 kg), they were painted white to achieve adequate thermal control in the harsh environment of low-Earth orbit and were fitted with electrical heaters to keep their components above minimum temperature levels. Affixed to the back of each MMU were two propellant tanks, which supplied 24 tiny thrusters with a total of 39 pounds (18 kg) of high-pressure gaseous nitrogen. To operate the thrusters, the astronaut used hand controllers at the end of two armrests: one provided roll, pitch, and yaw control, whilst the other allowed him to move forward, backward, up, down, and from left to right. Furthermore, by using both in unison he could achieve very intricate movements.

Particularly useful for repair missions, when a desired orientation had been reached, he could activate an automatic, “attitude hold” function to free his hands for work. Electrical power came from a pair of silver zinc batteries, capable of supporting the MMU for up to six hours of autonomous flight as far as 460 feet (140 meters) from the shuttle. In fact, one of the MMU’s widely publicized features was that its wearer did not need to remain attached to the spacecraft by a tether. Of course, in the event of problems, most of its systems were redundant and neither McCandless or Stewart ventured so far from Challenger that the pilots would not be able to rescue them if necessary. “We didn’t want to come back and face their wives if we lost either one of them up there,” joked Vance Brand.

As circumstances would transpire, the MMU trials would prove the singular greatest success of Mission 41B, as will be explored in tomorrow’s history article.

The second part of this history article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Yup. I’m a 100% USDA Certified Prime geek. I have the top-most photo of McCandless in the MMU framed and on my wall.

Thirty years ago I was serving as an engineering officer aboard USS McCandless (FF-1084), and a few weeks before CAPT McCandless’ flight, he and COL Stewart visited the ship and took a short voyage with the crew, family and friends (a “Dependents’ Cruise”). It was an honor to have CAPT. McCandless come and ride the ship named for his father and grandfather, and he took a few of our ship’s baseball caps into space with him, as I recall. After his flight, he kindly sent an autographed print of the famous photo (top) of him in the MMU, which we had framed and hung in the ship’s wardroom.