It is a dismaying fact of history that the name “Challenger”—when spoken in relation to the second spaceworthy vehicle of NASA’s shuttle fleet—is so often associated only with the dreadful catastrophe which snuffed out seven lives on the cold morning of 28 January 1986. However, Challenger had flown nine successful missions before tragic STS-51L, during which she delivered several major satellite payloads into orbit, transported 46 individual astronauts beyond Earth’s “sensible” atmosphere, supported six EVAs, and might have gone on to deliver the shuttle’s first planetary-bound emissary toward Jupiter.

Thirty-five years ago today, on 30 October 1985, Challenger embarked on her last fully successful mission—a mission which would stand until the end of the shuttle era as the only human spaceflight to both launch and land with as many as eight crew members.

Sadly, only four of those crew members are still with us, following the tragic death of German Payload Specialist Reinhard Furrer in an aircraft accident in September 1995 and the untimely passing of Dutch Payload Specialist Wubbo Ockels in May 2014, Commander Hank Hartsfield in July 2014, and Pilot Steve Nagel in August 2014. The others—Mission Specialists Bonnie Dunbar, Jim Buchli and Guy Bluford and German Payload Specialist Ernst Messerschmid—are therefore the only surviving members of the largest crew ever to launch into space on a single vehicle.

Their flight, STS-61A, carrying the Spacelab D-1 (for “Deutschland”) facility, had been principally financed by West Germany, although the European Space Agency (ESA) had contributed a 40-percent share, in return for having one of “its” astronauts (Ockels) aboard Challenger as a unique third Payload Specialist. It was the only occasion in the 30-year shuttle program that as many as three Payload Specialists flew aboard the same mission, although plans existed in the pre-Challenger era for a similar number of non-career astronauts to fly aboard the Sunlab-1 mission in mid-1987.

As with the later flight of STS-73, described in a previous AmericaSpace article, Spacelab D-1 was an around-the-clock operation, with the crew divided into two shifts—the “Red Team” and the “Blue Team”—to run a range of scientific and technical experiments throughout the mission. The Red Team was led by Buchli, who oversaw Challenger’s flight deck during his 12 hours on-shift, whilst Bluford and Messerschmid focused on the research inside the pressurized Spacelab module.

Meanwhile, the Blue Team was led by Nagel, with Dunbar and Furrer working the science. Hartsfield and Ockels maintained flexible timelines, anchoring their schedules across both shifts, usually in line with the Blue Team.

Due to the 24-hour activities, the respective halves of the STS-61A crew were required to “sleep-shift” in the days preceding their launch on 30 October 1985. “Jim, Ernst and I had to do a circadian rhythm shift, so, for us, the launch was coming near the end of our work day,” remembered Bluford in his NASA oral history. “While in quarantine, one team was up while the other was in bed. A new lighting system had been installed in the crew quarters to facilitate the shift in circadian rhythm. Once we got on-orbit, the Blue Team activated Spacelab, while the Red Team went to bed. We had four soundproof bunks to sleep in, while the Blue Team was at work.

“The two-shift operations worked very well on-orbit, with both teams up at the same time during breakfast and dinner, when we transferred Spacelab operations. The simultaneous transfer of responsibility—both on-orbit, as well as on the ground—went smoothly, as we exchanged information and updated our Flight Data Files. Each of the crew shared a sleep bunk with a member from the opposite team.”

Even STS-61A’s launch time of 12:00 noon EDT—“banker’s hours”, as Dunbar later joked—had been carefully timed for maximum television coverage in West Germany. Dunbar, Bluford and Nagel had been training since February 1984, with NASA having noted at the time that it intended “to have three-member crews share flight deck responsibilities on future Spacelab-type missions”. Six months later, in August, Hartsfield and Buchli were attached to Spacelab D-1, which had by then also gained its trio of Payload Specialists.

In her NASA oral history, Dunbar remembered that her early training brought her face-to-face with some of the same prejudices which she had seen as a young woman, trying to enter an engineering career. Many of the West German medical experiments for Spacelab D-1 were not intended to include female blood and there existed concerns that it might ruin their data.

Equally, the Vestibular Sled, which would run along the center aisle of the Spacelab module, did not fit her and it was George Abbey, then-head of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate (FCOD), who came to her aid and insisted that the Germans redesign their equipment to the percentile spread which included Dunbar.

As training progressed, she learned German and developed a good working relationship with her crewmates, including Reinhard Furrer. There was occasional time for banter, too, particularly when Furrer expressed astonishment that Dunbar had never heard of the television show Dallas. When he first asked her about it, she was convinced he meant the Texan city, but to be fair her engineering career had consumed her and watching television had been the last thing on Dunbar’s mind.

Although the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, retained overall control of the mission, the German Space Operations Centre (GSOC) at Oberpfaffenhofen, just outside Munich, managed daily research activities. Over the course of the mission, this worked well, with the exception that Oberpfaffenhofen’s limited data-transmission facilities meant that a number of functions had to be overseen by JSC.

Moreover, with only one Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) operational at the time, Spacelab D-1 received minimal communications coverage for 30 percent of each orbit and it was left to the Intelsat V geostationary satellite to relay data to an Earth station at Raisting in Bavaria and from thence to Oberpfaffenhoften, via microwave link.

Despite the focus of the mission and the common language always being English, on a few occasions German was spoken over the space-to-ground communications link, including one opportunity for Messerschmid and Bluford to speak to the head of Bavaria.

“The conversation was conducted in German with Ernst doing all the talking,” Bluford remembered years later. “Although the mission’s dialogue was conducted primarily in English, infrequently, the Payload Specialists would revert to German during on-orbit discussions.” Hartsfield remembered that the decision was a controversial one, with the Germans insisting that their language be spoken to controllers at a German site in Bavaria.

“I opposed that, for safety reasons,” he explained. “We can’t have things going on in which my part of the payload crew can’t understand what they’re getting ready to do. It was clearly up front: the operational language will be English. We finally cut a deal…that in special cases, where there was real urgency, that we could have another language used, but before any action is taken, it has to be translated into English so that the commander or my other shift operator lead and the payload crew can understand it.”

For Steve Nagel, Spacelab D-1 offered him the chance to fly a second shuttle mission within just four months in 1985, creating a personal landing-to-launch record which would endure for more than a decade. Originally named as a member of Mission 51A, planned for October 1984, Nagel’s first flight was repeatedly postponed and eventually flew as STS-51G in June 1985.

However, his second flight didn’t move; it was scheduled right from the start to fly in October 1985. He spoke to STS-51G Commander Dan Brandenstein, who talked to Abbey and negotiated for Nagel to remain on both missions. “I don’t think they’d ever do that today,” Nagel reflected, years later, “so I owe Dan for the fact that I was able to hang onto both of those.”

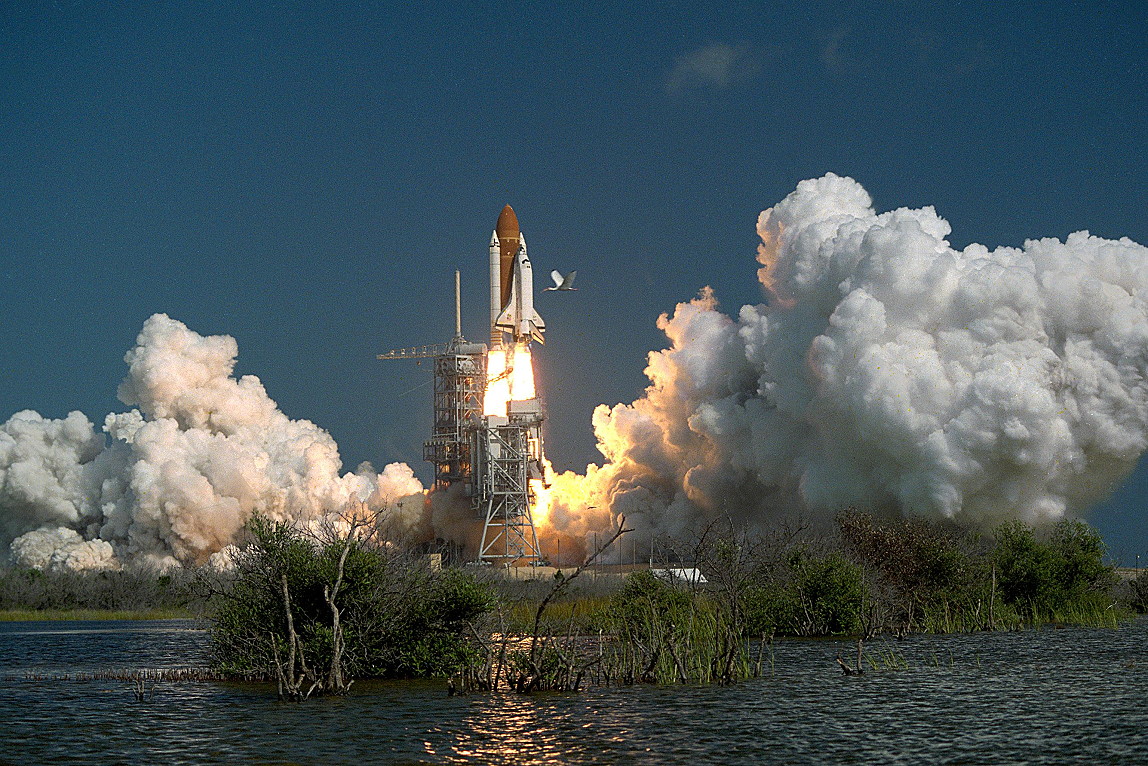

As a result, when Challenger rose from historic Pad 39A at the stroke of midday on 30 October 1985, a mere 128 days separated Nagel’s first shuttle landing and his second shuttle launch. This record would not be broken until the summer of 1997. But Nagel can have had little time to ponder his good fortune, for he also occupied a different role on his second flight, moving from a Mission Specialist to the Pilot’s seat.

In the seconds after liftoff, as Hartsfield and Nagel monitored their instruments, a “considerable” 102-degree “Roll Program” maneuver positioned Challenger onto the proper flight azimuth for a 200-mile (320 km) orbit, inclined 57 degrees to the equator.

The next seven days would be the last time that Challenger ever flew in space.

There should have been a Spacelab D-3 which was cancelled by the German government before D-2 launched.

It meant that neither female payload specialist candidates Heike Walpot or Renate Brummer ever got to fly in space. In fact this led to the Die Astronautin work in project to privately fund a German female on an orbital spaceflight.

Perhaps one of the women shortlisted will be selected as an ESA astronaut candidate next year, thereby guaranteeing a flight into space for a German female?