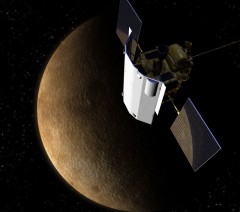

Often being neglected by the media and the general public, NASA’s MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging spacecraft, or MESSENGER for short, nevertheless continues to return exciting scientific results from its study of the Solar System’s innermost planet along the way. The intrepid robotic explorer has recently passed another milestone in its ten-year-old mission by completing its 3,000th orbit of Mercury earlier last month, while entering its final year of operations around the first rock from the Sun.

Although being briefly visited by the Mariner 10 spacecraft during the mid-1970s, Mercury had remained the least explored of the terrestrial planets since the dawn of the Space Age. Positioned deep inside the Sun’s gravity well, the planet presents one of the most challenging destinations in the inner Solar System. Despite the difficulties involved with the exploration of this fascinating world, a new age of discovery began with the launch of the low-cost Discovery-class MESSENGER mission in August 2004.

After conducting a total of six flybys around Earth, Venus, and Mercury over a period of seven years in order to decelerate enough to finally be captured by the latter’s gravity, MESSENGER finally became the first-ever man-made object to enter orbit around the scorched, fast-moving planet, in March 2011. Following the successful conclusion of its primary science operations in March 2012, MESSENGER’s mission was extended two times by NASA in 2012 and 2013, in the hopes of answering a new series of questions about the planet that had been raised during the primary science phase. As part of its extended mission, the spacecraft also re-adjusted its highly elliptical orbit around Mercury from 12 to eight hours, as part of a low-altitude imaging campaign to provide scientists with even higher resolution views of the planet’s surface features.

Following the start of MESSENGER’s second extended mission earlier this year, the spacecraft completed its 3,000th orbit around the planet on April 20, while decreasing its orbit to as close as 199 km above the surface. “We are cutting through Mercury’s magnetic field in a different geometry, and that has shed new light on the energetic electron population,” says Ralph McNutt, MESSENGER’s Project Scientist. “In addition, we are now spending more time closer to the planet in general — and that has, in turn, increased the opportunities for all of the remote sensing instruments to make higher-resolution observations of the planet.”

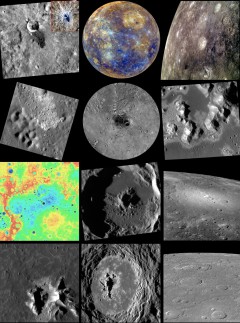

After completing the mapping of the planet’s entire globe in high-resolution near the end of its first extended mission, the spacecraft achieved another milestone in early February by beaming back more than 200,000 images to scientists here on Earth. “Returning over 200,000 images from orbit about Mercury, is an impressive accomplishment for the mission, and one I’ve been personally counting down for the last few months,” says APL’s Nancy L. Chabot, a MESSENGER Instrument Scientist for the spacecraft’s Mercury Dual Imagine System, or MDIS, at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md, which manages the whole mission for NASA. “However, I’m really more excited about the many thousands of images that are still in MESSENGER’s future, especially those that we plan to acquire at low altitudes and will provide the highest resolution views yet of Mercury’s surface.”

The huge volumes of data that have been gathered so far have shed new light to this fascinating world, revealing new clues about its surface geology, chemical composition, exosphere, and magnetic field, while yielding some unexpected surprises. For instance, the spacecraft found that the planet’s internal magnetic field is offset by 20 percent north off the planet’s center. In addition, the magnetometer onboard MESSENGER found that an asymmetry exists in the field’s geometry, with the magnetic lines converging differently in the geographical north pole than in the south, leaving the latter more exposed to the flow of energetic particles from the solar wind. The magnetometer’s results also revealed that even though the strength of Mercury’s magnetic field is just 1 percent that of Earth’s, it nevertheless is strong enough to create a magnetosphere that can trap solar wind particles, creating bursts of energetic plasma particles in its magnetotail. “While varying in strength and distribution, bursts of energetic electrons — with energies from 10 kiloelectronvolts (keV) to more than 200 keV — have been seen in most orbits since orbit insertion,” says McNutt.

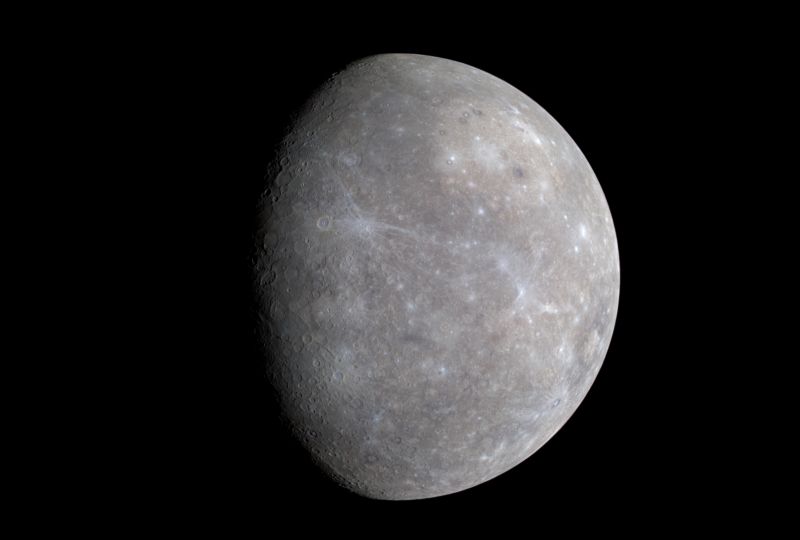

The study of the planet’s topography and chemical composition revealed several surprises as well. While the images that were beamed back from Mariner 10 during its three flybys of the planet in the mid-1970s revealed a world very similar in appearance to the Moon, the data gathered with MESSENGER showed that Mercury was a truly distinct world, fascinating on its own right and very different in many regards from the Earth’s natural satellite. Although the surfaces of both planetary bodies show similar geologic features, like impact craters and evidence of past volcanic activity, many others are unique to Mercury. “With MESSENGER in orbit, we are starting to see features in high-resolution images that are unlike anything on the Moon,” writes Dave Blewett, a MESSENGER Participating Scientist, at the mission’s website. “Even from Mariner 10 it was clear that Mercury’s smooth plains are not dark, whereas the Moon’s smooth volcanic mare plains are dark. Mariner 10 also revealed Mercury’s astounding, distinctly non-lunar, abundance of lobate scarps, formed by global contraction … On Mercury there is abundant evidence for volcanic activity involving the flow of lava; the style is similar to that of the Moon but differs in detail. So far we have observed only a few features that may have formed from lava erosion on Mercury, while there are about 200 observed on the Moon, indicating that there are differences in volcanic processes between the two planetary bodies … The data returned by the spacecraft shows that Mercury is radically different from the Moon in nearly every way that we can measure, including composition, internal structure, surface geology, magnetic field, charged particle environment.”

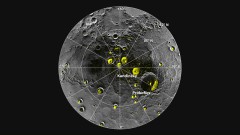

One of the biggest surprises, however, has been the discovery in 2012 of water ice deposits and possibly organic material on permanently shadowed craters on the planet’s polar regions, something that had been indicated by previous ground-based radar observations during the early 1990s. The confirmation came through a series of measurements of the polar regions’ hydrogen mineral composition that were taken with the spacecraft’s Neutron Spectrometer, or NS, and the measurement of their reflectivity at near-infrared wavelengths with the Mercury Laser Altimeter, or MLA. “The neutron data indicate that Mercury’s radar-bright polar deposits contain, on average, a hydrogen-rich layer more than tens of centimeters thick beneath a layer 10 to 20 centimeters thick that is less rich in hydrogen,” says David Lawrence, a MESSENGER Participating Scientist. “The buried layer has a hydrogen content consistent with nearly pure water ice.” “Water ice passed three challenging tests and we know of no other compound that matches the characteristics we have measured with the MESSENGER spacecraft,” says Sean Solomon, MESSENGER Principal Investigator. “These findings reveal a very important chapter of the story of how water ice has been delivered to the inner planets by comets and water rich asteroids over time.”

More surprisingly, similar evidence for the existence of water ice were recently found at a pair of craters as well, which are located far away from the planet’s poles, 66 degrees north of the equator. In addition, the polar craters inside which the water ice deposits were found were also found to be covered with a dark insulating material likely helping to preserve the ice underneath it intact. “The real surprise is that there were dark areas surrounding bright areas that were more pervasive than radar bright areas,” says Gregory Neumann, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “They are a blanket that protects the bright volatiles that lie underneath.” “Do the dark materials in the polar deposits consist mostly of organic compounds?” asks Solomon. “What kind of chemical reactions has that material experienced? Are there any regions on or within Mercury that might have both liquid water and organic compounds? Only with the continued exploration of Mercury can we hope to make progress on these new questions.”

MESSENGER is expected to continue operations in orbit around Mercury until early 2015, by which time the spacecraft will have depleted all of its fuel reserves and end its mission with a death plunge toward the planet’s surface. Before that happens, the mission’s science team hopes that the spacecraft will keep providing close-up views of Mercury in unprecedented resolution, during the mission’s low-altitude imaging campaign. “The final year of MESSENGER’s orbital operations will be an entirely new mission,” says Solomon. “With each orbit, our images, our surface compositional measurements, and our observations of the planet’s magnetic and gravity fields will be higher in resolution than ever before. We will be able to characterize Mercury’s near-surface particle environment for the first time. Mercury has stubbornly held on to many of its secrets, but many will at last be revealed.”

Following the end of the MESSENGER mission sometime during next year, our next opportunity to further study the planet closest to the Sun will be in January 2024, when the joint ESA/JAXA BepiColombo spacecraft, which is currently under development, will arrive at Mercury after being launched in July 2016. If the results from the MESSENGER mission are any indication, what new exciting discoveries will await us by then in orbit around the first rock from the Sun?

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Great article.

I have followed the Messenger spacecraft, online, since the beginning of its flybys and have visited the Messenger website daily since it entered orbit. The discoveries Messenger has made have been truly eye opening. Aside from LRO and the Mars rovers, it is the most significant mission currently occurring within the solar system.

Thank you B. Pohnan! Indeed, MESSENGER is a trully fascinating mission, revealing more about a trully intriguing world. I look forward to the results from the final year of its extended mission.

Leonidas’s article adds to the wealth of knowledge we are accumulating about our solar system. Mercury is as important to our understanding as are the other planets and moons in our “neighborhood.” Great work, Leonidas!

Thank you Tom! Indeed, MESSENGER is one of the most fascinating planetary missions currently operating. I’ll be following it closely for more exciting news in the future.

Best regards.