See our launch videos and photos below

WALLOPS ISLAND, VA — Over 150 totally thrilled university students and their mentors and instructors from all across America watched in awe as their research experiments to sniff Earth’s atmosphere, search for potential extreme life forms, and capture physical measurements thundered to space from NASA’s beachside Wallops Flight Facility launch complex in Virginia early Thursday morning. And with that successful liftoff they officially became America’s newest “rocket scientists!”

The students were participating in the seventh annual RockOn! workshop, conducted by NASA Wallops in partnership with the Colorado and Virginia Space Grant Consortia and Orbital Sciences Corp. During the week long STEM workshop from June 21-26, the students and teachers learned the intricacies of how to build a science payload for integration into a suborbital rocket. It’s the first step in a rocket science career for tomorrow‘s space leaders.

The “RockOn” payload blasted off atop a Terrier-Improved Orion suborbital sounding rocket at 7:21 a.m. on Thursday, June 26, 2014, from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility along the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

See our exclusive onsite photos and videos above and below.

“It’s a hands on, real world learning experience,” Chris Koehler told AmericaSpace in an exclusive interview at the Wallops launch pad. Koehler is Director of the Colorado Space Grant Consortium that manages the RockOn program in a joint educational partnership with NASA.

And it’s getting bigger and better.

“This year’s RockOn is great and our biggest program ever. We have so many more folks interested,” Koehler told me. “Why? Because space is exciting!”

“It’s good to know people are interested in this. And we have lots of new schools involved. That’s exactly what I want.”

“RockOn!” is the first of three practical STEM educational programs where the college students must master increasingly difficult skills and build science experiments that ultimately streak skyward on a pair of sounding rocket launches over the summer. Many of the starting level students move up to RockSat-C and RockSat-X—the intermediate and advanced level rocket science programs.

The RockOn students learned the basics of math and physics as it applies to rocketry and the experiments “through a PowerPoint instruction involving over 1200 slides during the workshop,” Koehler told me.

“We have 21 payloads they built here over three days by teams of three. It has a Geiger counter with a fully programmable microcontroller with accelerometers, gyroscopes, pressure, temperature and humidity sensors.”

“We also have five RockSat-C experiments built by RockOn students who were here before.”

“The students constructed their experiments from kits developed by myself and other students involved with the Colorado Space Grant Consortium that had just been refreshed last year,” Koehler said.

“The experiments acquired measurements of Earth’s physical and weather properties as well as rocket flight dynamics like acceleration, spin rate, radiation, humidity, pressure and temperature.”

“We walk though the kits step by step so that the students build a flight qualified piece of hardware through a very rigorous process,” Koehler explained.

The 659.2-pound science payload also included RockSat-C level experiments from Mitchell Community College, Statesville, North Carolina; West Virginia University, Morgantown; Carthage College, Kenosha, Wisconsin; Temple University, Philadelphia; and Howard University in Washington.

“The RockOn! and RockSat-C programs are part of an effort to expand students’ skills in developing experiments for spaceflight,” said Koehler. “These two programs, coupled with RockSat-X, which requires an even more advanced skillset, will help prepare these students for future careers in the aerospace industry and at NASA.”

“The goal is to provide University students with the opportunity to design, build and fly a rocket science payload so they get a real world experience of engineering and designing everything at their schools,” said Rebecca Lidvall in an interview, coordinator of RockSat-C for the Colorado Space Grant Consortium.

“Then they come here to check in and integrate their payload and launch it. It has to meet certain requirements.”

“So they fly it and see what happened, if it worked, did anything break, and they fix it.”

“The experiments this year come from five teams. One involved ferro fluids suspension that change shape in a magnetic field in microgravity. Two more experiments involve atmospheric collections to compare greenhouse gas model predictions with actual measurements from the flight.”

“Another experiment is to see if there are any living organisms in the atmosphere to see if there is any potential for living organisms at other planets.”

“To capture the atmospheric constituents there are four valves that open up in the middle section of the rocket where the payloads are housed which lead to tubing. The valves and tubing have been designed to open at certain altitudes going up and then close on the way down before we hit the ocean,” Lidvall explained.

So the valves and tubes are open for several minutes of collection during the parabolic arc.

“There is also a gravity gradient boom system as a proof of concept for satellites and it includes a camera to capture images and transmit data in real time. There are two student ground stations with receiving antennas set up here in the beach side viewing area for the flight to try and capture science telemetry,” said Lidvall.

“It’s a nearly yearlong program altogether.”

The entire science team gathered in predawn darkness at the beachside viewing site barely a quarter mile away ahead of the planned 5:30 a.m. liftoff. And AmericaSpace was excited to be on hand for an eyewitness account.

Several “gaggles of [errant] boaters” as well as local overnight thunderstorms and windy conditions aloft briefly delayed the liftoff until a virtually clear blue sky suddenly burst forth to universal delight.

Everyone counted down the last 10 seconds in unison and erupted in exuberant cheers as Wallops Mission control resumed the count and ignited the first stage solid rocket motor.

Watch our launch video compilation below shot by Ken Kremer and Brent Houston.

The Terrier-Improved Orion blasted off in a flash with a shockingly loud thunderous boom that sent nearby car alarms shrieking. It was literally gone in an instant as we almost instantly craned our necks skyward and virtually straight up to watch the majestically evolving contrail of smoke and ash.

The rail launched Terrier-Improved Orion flew on a parabolic arc to an apogee of 73.3 miles. It splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean 43.9 miles downrange from Wallops Island and impacted exactly 12.16 minutes after liftoff.

The experiments had been carefully loaded inside the approximately 10-foot-long payload section at the top of the 33-foot-long rocket.

“Every participant signed their names on the rocket’s outside,” said Dimitris Vassiliadis, Research Associate Professor with the RockSat-C team from West Virginia University.

After first stage burnout we could distinctly hear it plummeting back to Earth and smash uncontrollably into the ocean with a loud thump, some three to four miles off shore.

The nose cone and payload section were recovered by a team comprising a commercial fishing boat and NASA and Orbital Sciences technicians who brought it back to the Wallops rocket facility on a flat bed truck about six hours later.

The students then retrieved their experiment packages and immediately began evaluating the instruments and analyzing the data captured.

Some student telemetry and science data was successfully received from the rocket during the flight.

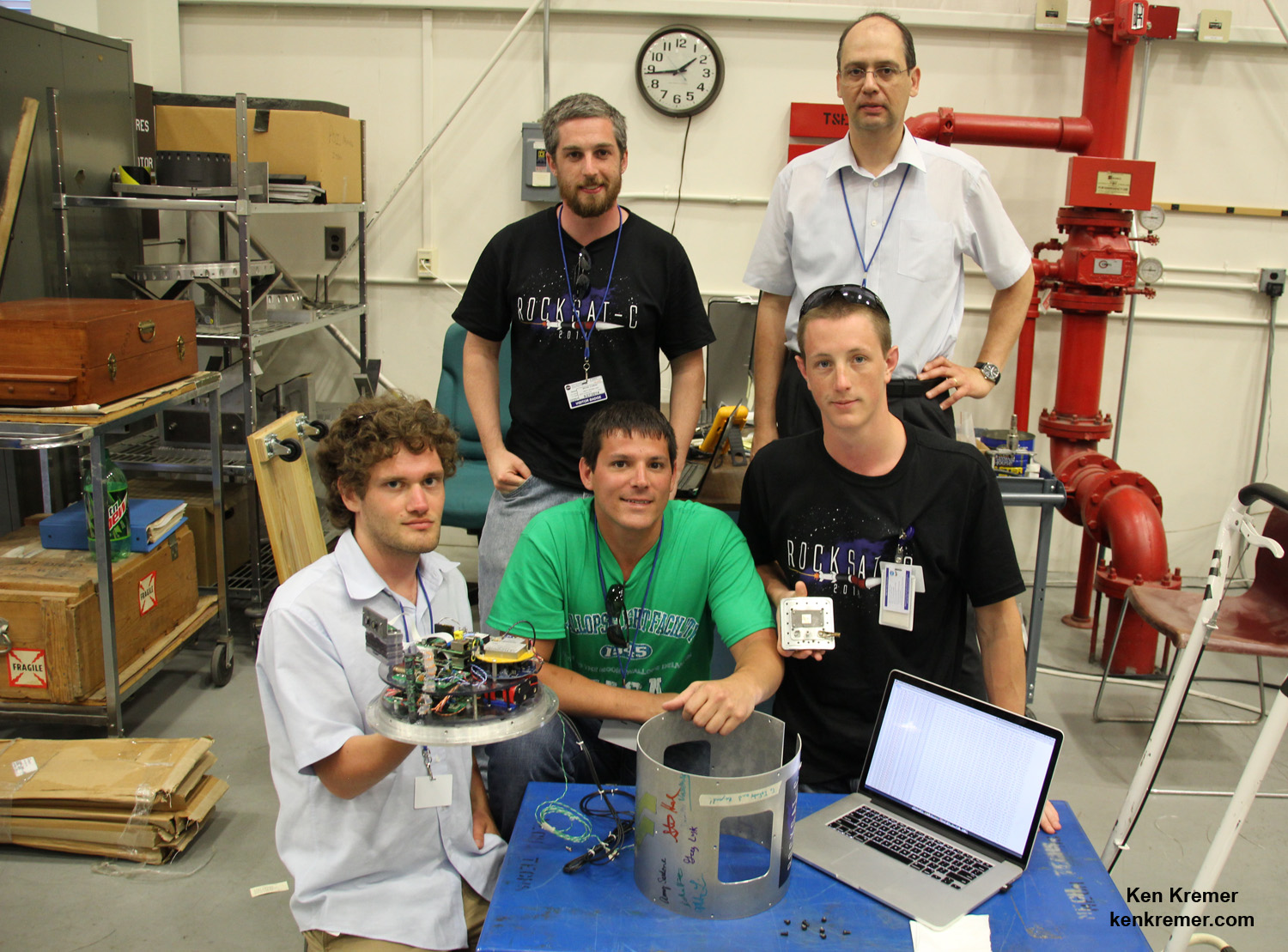

One of the RockSat-C University teams I spoke in detail with was from Morgantown, W.V. See photo.

“The experiments we flew this morning included measurements of plasma dynamics, the magnetic field, flight dynamics as well as two cameras with two different filters to obtain measurements of upper-atmospheric constituents,” Dimitris Vassiliadis, Research Associate Professor with the RockSat-C team from West Virginia University, told me in an interview.

“We measured the plasma density in the Earth’s ionosphere using a Langmuir probe, basically an electrode whose voltage we vary and we obtain the current. We obtained a nice-looking, noisy, but realistic current-voltage (I-V) curve at various altitudes. From that we may be able reconstruct a profile of density versus altitude.”

“We measured the B field [magnetic field] using two micromagnetometers. The measurements are modulated by the rocket’s rotation (the X direction becomes Y, then becomes -X, then -Y, etc) so we need to deconvolve the data to obtain the field as a function of altitude. This physical variable is also key for understanding charged-particle (=plasma) behavior.”

“Another also measured flight dynamics variables related to the acceleration and rotation rate of the vehicle. We have captured these variables using a miniature ‘inertial measurement unit’ (IMU), a cube only 1/2 an inch across containing 3 accelerometers, 3 gyroscopes, a temperature sensor, and a magnetometer. These are key to understanding all other measurements (such as the magnetic field). In this vehicle acceleration and rotation vary at different parts of the flight so care must be taken to reconstruct the actual rates from the instantaneously measured ones,” Vassiliadis explained.

Do you want to be a rocket scientist?

Well here’s your chance, and this is the definitely the program for you in my opinion as a research scientist.

New students can apply soon for the 2015 RockOn and RockSat programs. Many of the students I met will return next year with experimental upgrades and new ideas!

“Everyone is pretty darn excited!” Koehler beamed.

“Build a little, Fly a little,” that’s the rocket scientists mantra.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace