Those of us who are alive today should consider ourselves fortunate that our lives overlapped with those of the first humans to visit another world. Homo Sapiens evolved 300,000 years ago, and our species will hopefully continue to thrive for hundreds of thousands of years to come. Yet, in that vast span of time, the Apollo astronauts occupy a unique place in history. Unfortunately, their era is rapidly receding into the past. We received a painful reminder of this on Monday, March 18th. On Monday, General Tom Stafford, one of the most distinguished Gemini and Apollo commanders, passed away at the age of 93 after a battle with liver cancer.

While he did not walk on the Moon, Tom Stafford’s contributions to NASA were indispensable. For 13 years, Stafford was at the crux of the “Space Race” between the United States and the Soviet Union. During this period, he completed four high-profile missions. He participated in the first rendezvous between two spacecraft, helped the Gemini program recover from a tragic accident, and led the dress rehearsal for Apollo 11. Ultimately, he brought the Space Race to a poignant conclusion when he docked the final Apollo Command Module with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft piloted by two cosmonauts. As we look back on his storied career, we should celebrate a life well lived at the forefront of exploration.

Stafford grew up in the Oklahoma countryside. His mother was a teacher, while his father was a dentist. In his autobiography, “We Have Capture,” Stafford shared his reflections on his long life. He wrote, “Summer nights were so hotthat the family would take cots out back and sleep under the stars. My father knew some of the constellations, and he would point them out to me. I would look at the Moon, which seemed so close, and wonder whether we would ever touch its surface.”

Stafford’s passion for aviation developed during World War II, and it drove him to join the U.S. Air Force after he graduated from college. Over the course of his career as a pilot, he flew 120 different types of aircraft. He spent many of his flight hours inside the cockpit of the iconic F-86 Sabre. Stafford served during the peak of the Cold War, and during their deployments, his squadron was tasked with protecting Alaska and West Germany from encroaching Soviet bombers and surveillance aircraft.

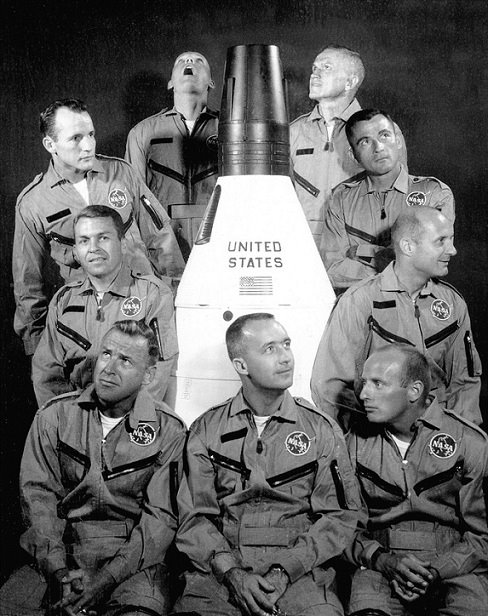

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy challenged NASA to land a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. Stafford recalled, “Go to the Moon? Now that was exciting. I was really charged up about the idea, and for the first time, I got interested in joining the space program.” In 1962, he and eight other elite test pilots were selected to join the second class of astronauts.

After his class completed basic training, Stafford received a coveted flight assignment. He was slated to accompany Alan Shepard, America’s first astronaut, on the inaugural manned flight of the Gemini program. Shepard and Stafford’s three-orbit Gemini 3 mission would have demonstrated the advanced capabilities of the Gemini spacecraft, particularly on-orbit maneuvering, to prepare for future missions. If Gemini 3 had flown as planned, Stafford would have become the seventh American, as well as the first astronaut from outside of the original “Mercury Seven,” to fly in space.

However, fate dictated a different outcome. While he was delivering a lecture, Shepard experienced a sudden bout of nausea. Flight surgeon Chuck Berry diagnosed him with Ménière’s Disease, an ailment of the inner ear which causes vertigo. Stafford was shocked. “Maybe I was selfish, but in the best pilot tradition, my question was, ‘What about me?’ Were Shepard and I a team? With him gone, was I gone, too?” Instead of forming a new commander-pilot duo just two months before launch, NASA replaced both Shepard and Stafford with their backups, Gus Grissom and John Young.

While Stafford was disappointed, he didn’t need to wait long for his first spaceflight. He was reassigned to Gemini 6 alongside Mercury veteran Wally Schirra. Ever since the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, NASA had lagged behind the Soviet space program’s achievements. Gemini 6 would go down in history as the flight which handed the United States its first lead in the Space Race.

However, it first encountered a dose of misfortune. Schirra and Stafford’s primary task was the first rendezvous and docking in space. Their target was an Agena vehicle, a 26-foot-long upper stage with a docking adapter on its nose. According to the nominal mission plan, the two men would launch from Launch Complex 19 just ninety minutes after the Agena launched from neighboring Complex 14. As Stafford and Schirra waited inside their cramped Gemini capsule, the Agena launched on schedule. Stafford wrote, “Everything was going great until fourteen minutes after the Agena’s launch, when it should have appeared in the sky over Bermuda – and didn’t.” As he listened in to the launch team’s communications, Stafford realized that the Agena had exploded.

Mastering orbital rendezvous was one of the primary objectives of Project Gemini. With a lengthy anomaly review looming, McDonnell executives Walter Burke and John Yardley hatched a bold plan: Gemini 7 could serve as an alternative rendezvous target for a redesignated Gemini 6A mission. While their proposal was initially greeted with skepticism, it was thoroughly analyzed and eventually approved by NASA management. Frank Borman and Jim Lovell’s Gemini 7 mission launched on December 4th, 1965. In an impressive feat, the NASA team at Cape Canaveral primed a second Titan booster and Gemini spacecraft to launch from the same pad just eight days later.

Stafford and Schirra boarded their spacecraft, but once again, the countdown did not go according to plan. The Titan’s two main engines ignited… and then abruptly shut down after 1.2 seconds. The crew had to make a split-second decision. If the rocket had indeed lifted off, they needed to eject before it fell back onto the launch pad and exploded in an apocalyptic conflagration. Schirra, however, did not feel any motion, and he declined to pull the ejection handle. Stafford was grateful for his commander’s good instincts. “Given that we’d been soaking in pure oxygen for two hours, any spark, especially the ignition of an ejection-seat rocket, would have set us on fire. We’d have been two Roman candles shooting off into the sand and palmetto trees.”

Three days later, Gemini 6A finally lifted off and began its pursuit of Gemini 7. In an era where computing power was limited, Stafford used a slide rule and a plotting chart to calculate his capsule’s position relative to Gemini 7. He relayed this information to Schirra, who completed the rendezvous and “parked” his spacecraft next to Gemini 7. Over the course of five hours, Schirra and Stafford maneuvered Gemini 6A around Borman and Lovell’s capsule. At one point, the two vehicles, both of which were travelling 17,500 miles per hour, were separated by just nine feet. The two crews definitively proved that it was feasible for Apollo’s Command and Lunar Modules to rendezvous in lunar orbit.

Since their mission took place just ten days before Christmas, Schirra and Stafford also played a practical joke on their flight control team. Stafford reported “an object, looking like a satellite, going from north to south,” which he clearly implied to be Santa Claus. As Schirra played “Jingle Bells” on a harmonica, Stafford accompanied him with a set of small bells.

Once he returned to Earth, Stafford was quickly assigned to serve as the backup commander of Gemini 9. According to Deke Slayton’s ironclad flight rotation system, he would then command Gemini 12, the final flight of the program. Tragically, the Gemini 9 prime crew, Elliot See and Charlie Bassett, lost their lives while trying to land their T-38 training jet on an overcast day. Flying in space was a risky profession, and NASA knew that a preflight accident was always a possibility. Thanks to their training, Stafford and first-time flyer Gene Cernan were prepared to complete See and Bassett’s mission. It was Stafford’s second spaceflight in under six months.

Once again, Stafford’s Agena target vehicle did not cooperate. Just two minutes after off, the Agena’s Atlas booster developed a short circuit in its servo control system and began tumbling. It ultimately crashed into the Atlantic Ocean. Johnson Space Center Director Bob Gilruth turned to legendary Flight Director Chris Kraft and remarked, “I wonder what Stafford is saying right now?” Kraft replied, “I don’t know, but you can bet that it isn’t ‘Aw, shucks!’” For his part, Stafford said that he was “tired, sweaty, and disappointed.” Once again, NASA scrambled to find an alternative target for a Gemini mission. This time, Stafford would rendezvous with an Augmented Target Docking Adapter (ADTA). The makeshift contraption was essentially an Agena without its fuel tanks and rocket motor attached.

Another scrub prompted Guenter Wendt, the leader of the Gemini closeout crew, to nickname Stafford the “Mayor of Pad 19” due to his bad luck on launch day. When Stafford and Cernan arrived in orbit, they discovered that all was not well with their docking target. The ADTA’s payload fairing had only partially separated, and it was held ajar by two lanyards which should have been removed before launch. Its appearance inspired Stafford and Cernan to nickname it the “Angry Alligator.” Due to the risks associated with approaching such an unstable vehicle, Mission Control ordered them to abandon the docking attempt.

Gene Cernan was still able to attempt America’s second spacewalk. Even before the mission, this objective had worried Stafford. Prior to the mission, Stafford and Deke Slayton, the Chief of Flight Crew Operations, had a conversation about what would happen if the unthinkable happened. Slayton ordered Stafford, “If he dies, you have to bring him back.” Stafford’s worst fears almost came to pass when Cernan overexerted himself due to the lack of suitable handholds on Gemini 9A. He lost ten pounds during the spacewalk, and his vision was completely obscured by a fogged visor. Thankfully, Cernan was able to use his sense of touch to feel his way back inside the capsule, whereupon he nearly lost consciousness. Stafford’s second flight alerted NASA to several knowledge gaps which it subsequently addressed prior to the first crewed lunar landing.

Much changed before Stafford returned to space on Apollo 10. For a time, he served as the backup Command Module Pilot for Apollo 2, an early test flight of the Apollo spacecraft. This flight was ultimately cancelled when astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee lost their lives in the tragic Apollo 1 fire.

Stafford was ultimately placed in command of Apollo 10. His crewmates were John Young and Gene Cernan, both of whom would later walk on the lunar surface. Designated the F-Mission in NASA’s parlance, Apollo 10 served as a dress rehearsal for the historic Apollo 11 lunar landing. After the nearly flawless success of Apollo 9, NASA management briefly considered tasking Apollo 10 with the first lunar landing. The media caught wind of the rumors and prepared extensive profiles on Stafford, who they anticipated to be the first man on the Moon. Stafford did not relish the assignment. In his autobiography, Cernan wrote, “Tom was not so adamant about being first on the Moon. He never looked at it that way. He wanted to do what was the best thing to do and have a coordinated, planned program.” Stafford ultimately got his wish when it became apparent that Apollo 10’s Lunar Module was too heavy to land on the Moon and return its crew to lunar orbit.

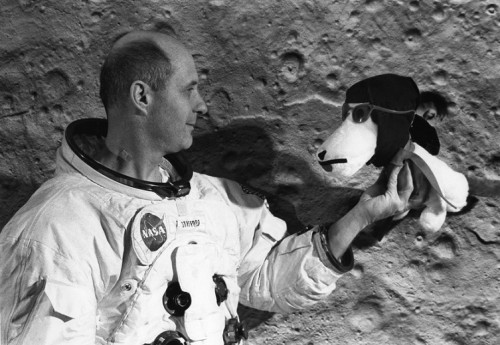

The Apollo 10 crew named their Command Module and Lunar Module “Charlie Brown” and “Snoopy,” respectively. According to Stafford, the LM’s name was a tribute to the NASA workforce. Beginning in 1968, the Astronaut Corps has handed out “Silver Snoopy” awards to employees who make crucial contributions to crew safety. Stafford remarked, “The choice of Snoopy was a way of acknowledging the contributions of the hundreds of thousands of people who got us (to the Moon).” For once, Stafford launched on schedule on May 18th, 1969. The only major issue with the launch was unexpected vibrations during the translunar injection maneuver. As Apollo 10 drifted away from Earth, Stafford peered through Charlie Brown’s windows through the first time. “Blue and white, the size of a basketball, Earth was literally shrinking before our eyes. For the first and only time in my space life, I felt strange. It was a long way from the windmill on that farm near May, Oklahoma.”

Three days later, Apollo 10 entered lunar orbit. “Tell the world we have arrived!”, Stafford exuberantly exclaimed during a television broadcast. When he described the far side of the Moon, he wrote, “It was full of unfamiliar mountains and craters and seemed pretty chewed up.” Shortly thereafter, the most pivotal segment of their mission began. Stafford and Cernan boarded Snoopy and undocked, leaving Young in command of Charlie Brown.

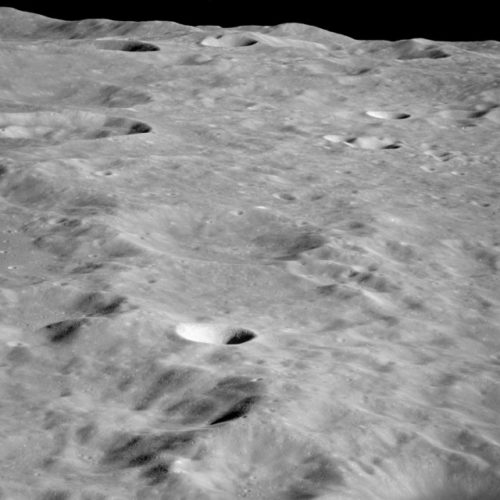

The two astronauts maneuvered their lander into a descent orbit with a perilune (minimum altitude) of a mere nine miles. Future Apollo missions would begin their powered descent at this point; instead, Stafford and Cernan took high-resolution photographs and made visual observations of the Apollo 11 landing site. From Stafford’s perspective, “Distances were hard to judge. We were only thirty-five thousand feet above the highest peaks, not much higher than a commercial airliner cruising over the surface of Earth, but since the Moon had no atmosphere, and thus no clouds, smog, or other distortions, you lacked the usual visual clues.”

During their ascent to rejoin Young in his circular lunar orbit, Stafford and Cernan tested the Abort Guidance System (AGS). In case Apollo 11’s descent went haywire, NASA needed proof that this key safety feature was dependable. Stafford was unaware that Cernan had previously set the AGS to the correct mode, and he flipped the switch for a second time. This inadvertent decision commanded Snoopy to autonomously search for a signal from Charlie Brown. The lander immediately began to tumble. “Son of a b****!”, Cernan shouted. Using instinctive skills honed through countless hours in simulators, Stafford jettisoned Snoopy’s descent stage and gradually restored control over the spacecraft. Stafford previously earned the callsign “Mumbles” because he would habitually swear under his breath on the radio. Cernan was incensed that NASA’s public affairs staff had edited out Mumbles’ frequent expletives, but failed to catch his outburst!

While it was overshadowed by the subsequent lunar landings, Stafford’s Apollo 10 mission played a vital role in the Apollo saga. Among other achievements, his crew proved that the CM and the LM could rendezvous in lunar orbit after a landing, that the Sea of Tranquility was relatively flat and free of hazards, and that the Moon’s irregular gravity field would not impede a descent to the lunar surface. During their return to Earth, they also set a speed record for a crewed spacecraft which still stands today. Given the obstacles which they encountered two months later, it is possible that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would have been forced to abort their landing if Stafford, Young, and Cernan had not retired these additional risks.

Despite the fact that he was one of NASA’s most experienced astronauts, Stafford never planted his boots in the lunar regolith. However, the leadership role which he assumed was just as important. When Alan Shepard assigned himself to Apollo 14, Stafford took his place as the Chief of the Astronaut Office. He handed out the final flight assignments of the Apollo era and represented his fellow astronauts in discussions with NASA management.

Shortly after he left his management post, Stafford received a unique assignment. During his Gemini and Apollo flights, Stafford played a vital role in winning the Space Race. During his final mission, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, he would help bring the geopolitical contest to a symbolic and moving conclusion. Stafford and his crewmates, Deke Slayton and Vance Brand, were tasked with docking to a Soviet Soyuz capsule crewed by cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov. The mission faced its fair share of barriers, ranging in nature from technical to linguistic. “We were learning to work together,” said Stafford. “But we still found it difficult to be completely open with each other.”

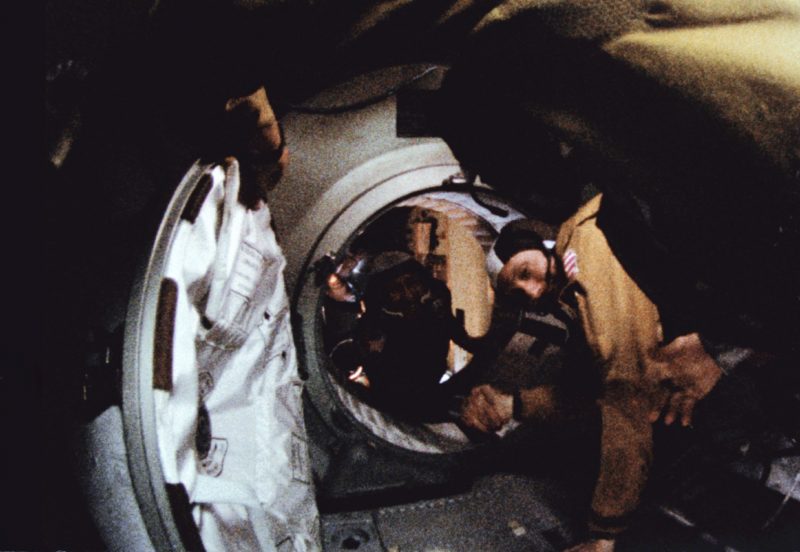

On July 15th, the final Saturn IB booster, crowned by the last Apollo capsule, raced skyward from Launch Complex 39B. After his crew reached orbit, Stafford executed a precise series of maneuvers to rendezvous with Leonov’s Soyuz. As the two spacecraft made contact, Leonov declared, “Soyuz and Apollo are shaking hands now.” A few hours later, Stafford and Leonov literally shook hands when they opened the hatches separating their vehicles. The “Handshake in Space” became one of the most iconic photographs of the space age, and it was the harbinger of a new era of cooperation between the world’s first two spacefaring powers.

For two days, the five astronauts and cosmonauts collaborated to complete an eclectic suite of biological science, Earth science, and heliophysics experiments. Apollo-Soyuz might seem like atypical and symbolic event conducted in the midst of larger space endeavors, but its significance reached far beyond the end of the mission. It was the first spaceflight to feature crewmembers from two different nations. They weren’t close allies, either – just 13 years earlier, America and the Soviet Union nearly annihilated each other during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Apollo-Soyuz set a precedent for diplomacy in orbit which expanded during the Space Shuttle era. It also proved that American and Russian engineers could work together to build hardware, despite differences in culture and in design philosophy. Stafford and Leonov proved that they were the right men to spearhead the joint effort. The mission succeeded because both commanders were able to accept outside perspectives and forgive occasional misunderstandings.

Stafford’s spaceflight career ended as dramatically as it began. The splashdown of Apollo-Soyuz nearly ended in tragedy when a vent inadvertently ingested a plume of nitrogen tetroxide from a maneuvering thruster. The compound quickly spread through the cabin. Stafford thought, “Nine days and three million miles, everything’s gone so good, and now here we are, locked upside down with this toxic gas in the spacecraft.” For reasons which remain unclear, Stafford displayed unusual resistance to the effects of the compound. “I knew we had to get oxygen. The masks were stored behind my seat – above and behind me in that position. It told myself, release the straps, get the masks, but don’t fall down the (docking) tunnel.” He quickly distributed oxygen masks to his unconscious crewmates, which probably saved the lives of all three men. It is fitting that Stafford’s calm and decisive actions mirrored Wally Schirra’s heroism during the Gemini 6A abort. Schirra likely saved Stafford’s life, and Stafford paid that forward to his two less experienced crewmates.

Stafford left NASA in 1975. He continued to serve his country in the Air Force for four more years, eventually rising to the rank of Lieutenant General. Stafford was one of the early advocates for stealthy combat aircraft, including the F-117 Nighthawk and the B-2 Spirit. He famously drafted the specifications for the B-2 on a single piece of paper during a conversation with the CEO of Northrop inside a hotel. When the B-1 bomber program was temporarily cancelled, he preserved the the prototypes by repurposing them to serve as high-speed research aircraft.

Stafford also retained a passion for spaceflight, and he advised NASA until shortly before his death. He served as a technical advisor for the Shuttle-Mir program, the ideological descendent of Apollo-Soyuz. Alongside other Apollo icons, including Neil Armstrong, Jim Lovell, Gene Cernan, and John Young, he advocated for the Constellation program when it was cancelled in 2010. Stafford helped convince the ordinarily reclusive Armstrong to testify before Congress, which had a major impact on the influential members of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. While Stafford and his colleagues could not save Constellation, their perspectives swayed Congress to fund a balanced portfolio of commercial and government programs which later morphed into the Artemis architecture. Perhaps most importantly, he served on the NASA Advisory Council for 30 years, sharing his wisdom with the next generation of explorers.

Stafford’s legacy is embodied by the International Space Station (ISS). While geopolitical tensions over nuclear arms control precluded an immediate successor to Apollo-Soyuz, the dynamic changed when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. NASA and Roscosmos, the space agency of the new Russian Federation, created the joint Shuttle-Mir program. These dockings, in turn, led to the ISS partnership. The construction of the ISS was the climax of the effort which began during Apollo-Soyuz, as both superpowers needed to sacrifice some autonomy and rely upon each other. American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts have lived together inside the orbital outpost for over 23 years.

It is heartbreaking that Stafford had to spend his final years on Earth watching his life’s work fall apart. A new Russian government, led by Vladimir Putin, shattered any near-term opportunities for cooperation in space when it launched a brutal invasion of Ukraine without casus belli. In the process, the Russian space program’s budget was gutted to funnel additional money towards the arms industry. However, Apollo-Soyuz established a model for international collaboration in space which will continue long into the future, even if the participants are different.

Stafford also incorporated a diplomatic attitude into his own life. He was close friends with Alexei Leonov until the famous cosmonaut passed away in 2019. Stafford said, “We were military pilots and officers who found common ground and adapted to changing circumstances. I believe that, together, we helped make that new world a somewhat better place to live.” Leonov was the godfather of Stafford’s sons, Michael and Stanislav; Stafford gave the eulogy at his former crewmate’s funeral.

Less than a year before his passing, Stafford reached out to Reid Wiseman, the commander of the next crewed mission to the Moon. According to Wiseman, the call was unexpected. “I almost missed a call from General Tom Stafford because I thought he was a telemarketer,” he remarked last August. “What really shocked me was how excited he was that we are going back to the Moon for the agency, for the nation, and for the planet.” With that phone call and his appearance at the Artemis 1 rollout, Stafford symbolically passed the torch to the Artemis generation. It is up to us to continue the journey which he started.

Stafford is a man who leaves behind a monumental legacy. Thanks to his autobiography and NASA’s meticulous records, his life will undoubtedly inspire subsequent generations for decades to come. In a world which is plagued by war and discord, we need more people like Tom Stafford. Safe travels, Commander.

Missions » Apollo »

One Comment

Leave a ReplyOne Ping

Pingback:Remembering Tom Stafford, the Space Races Peacemaker (1930-2024) – AmericaSpace | Prometheism Transhumanism Post Humanism