Returning humans to lunar distance on the Artemis II mission will not occur before September 2025, according to comments provided Tuesday by NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and senior agency leaders and industrial partners. Citing “an incredibly large challenge and a really big deal”, Mr. Nelson’s team pointed to the ongoing need to flight-qualify critical Artemis II environmental control and life-support components and derive a better understanding of an unexpectedly high loss of char-layer pieces from the Orion spacecraft’s heat shield during its December 2022 re-entry.

“We are returning to the Moon in a way we never have before and the safety of our astronauts is NASA’s top priority as we prepare for future Artemis missions,” said Mr. Nelson. “We’ve learned a lot since Artemis I and the success of these early missions relies on our commercial and international partnerships to further our reach and understanding of humanity’s place in our Solar System.

“Artemis represents what we can accomplish as a nation and as a global coalition,” the administrator added. “When we set our sights on what is hard, together, we can accomplish what is great.”

Announced to great international fanfare last April, the Artemis II crew will be commanded by former NASA Chief Astronaut Reid Wiseman, joined on the flight by Pilot Victor Glover and Mission Specialists Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen. Wiseman, Glover and Koch have all previously flown long-duration increments to the International Space Station (ISS)—logging more than 660 cumulative days in orbit and 12 spacewalks between them and setting empirical records for African-American spacefarers and female space travelers—whilst Hansen, a Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut, is set to become the first non-U.S. citizen to travel to the vicinity of the Moon.

The quintet will become the first humans to cross the 240,000-mile (370,000-kilometer) cislunar gulf between Earth and our closest celestial neighbor in more than a half-century, since Apollo 17 Commander Gene Cernan, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Ron Evans and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Harrison “Jack” Schmitt returned from the Moon in December 1972. Wiseman & Co. will launch atop the 322-foot-tall (98-meter) Space Launch System (SLS) from historic Pad 39B at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) for an anticipated ten-day voyage to lunar distance and back home.

Last summer, NASA expressed cautious confidence that Artemis II would occur in November 2024 as progress both on the SLS and Orion Crew Module (CM) and European Service Module (ESM) gained momentum. The CM’s 16.5-foot-diameter (5.02-meter) heat shield was installed last June and the spacecraft underwent acoustic testing in the high bay of the Neil Armstrong Operations & Checkout Building at KSC in August.

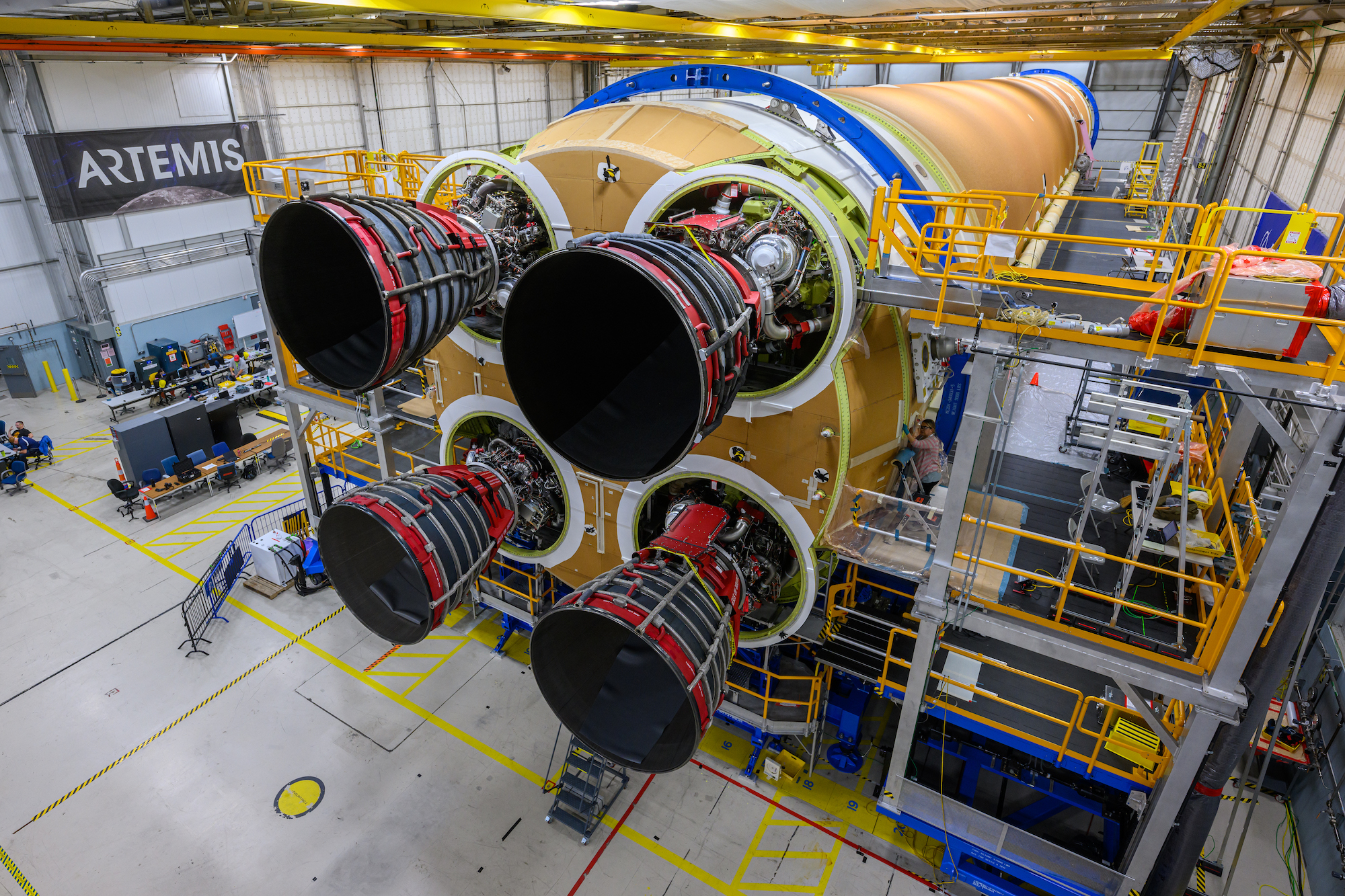

Elsewhere, the SLS Core Stage received its full complement of four RS-25 shuttle-era engines last September and also last summer the ESM was handed over by the European Space Agency (ESA) to NASA as work ramped up on its own heat shield, with final deposition anticipated early in 2024. Stacking of the SLS rocket’s pair of five-segment Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) was timetabled to begin in February.

Following launch, Wiseman, Glover, Koch and Hansen will fly a Multi-Translunar Injection (MTLI) profile, their Orion CM/ESM initially entering a high Earth orbit with a period of roughly 24 hours to permit the Artemis II crew to conduct extensive systems checkouts and a rendezvous and proximity-operations demonstration using the SLS rocket’s spent Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (iCPS). Once checked out satisfactorily, the spacecraft would conduct a TLI “burn” to emplace itself onto a free-return trajectory to carry it around the Moon and back to Earth.

In Tuesday’s media teleconference, Mr. Nelson noted that with the Artemis II crew “busy training”, the agency and its international partners—which now includes the United Arab Emirates (UAE), whose Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) will provide an airlock for the lunar-orbiting Gateway—are entering “a Golden Age of exploration”. But the administrator’s encouraging opening rhetoric was tempered by a widely anticipated announcement of a delay to the early crewed missions: Wiseman’s Artemis II moves from November 2024 to September 2025, the lunar-landing mission of Artemis III moves from late 2025 to no sooner than September 2026 and the Gateway-focused Artemis IV remains in its previous placeholder date of September 2028.

“Though challenges are ahead,” said Mr. Nelson, “our teams are making incredible progress.” Three key drivers have reportedly conspired to the almost-year-long Artemis II delay: a heat-shield issue observed during the Artemis I re-entry in December 2022, a failure within the Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) during acceptance testing and an ascent-abort issue pertaining to Orion’s batteries.

According to Amit Kshatriya, deputy associate administrator of the Moon-to-Mars Program within NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate (ESDMD), “some unexpected phenomena” was noticed during the first phase of Artemis I’s skip re-entry. There was, Mr. Kshatriya explained, some observed off-nominal “recession” of char-layer material from Artemis I’s heat shield that engineers did not anticipate.

Although some liberation of char was expected, teams are working to derive a better understanding of the char transport process, with support from industry and government partners. This will include core sampling and data reviews “hopefully in the spring” to ensure full confidence in heat shield performance. “Teams have taken a methodical approach to understanding the issue,” NASA explained, “including extensive sampling of the heat shield, testing and review of data from sensors and imagery.”

The second issue relates to the failure of motor valve drive circuits in the ECLSS, which were declared “passed” for Artemis II, but not Artemis III, revealing a design flaw in the Carbon Dioxide (CO2) scrubbing system. This is in the process of being redesigned and replaced, which upon completion will require a deep-dive into the Artemis II spacecraft—with access to the relevant equipment bays considered difficult to reach—and further post-reassembly diagnostics and full-up testing.

The third issue identified areas of the ascent trajectory in an SLS abort profile in which Orion’s batteries and connections might prove compromised. In his remarks, Mr. Kshatriya stressed that the spacecraft was fully qualified to survive a launch abort, but “a few” cases were discovered pertaining to deficiencies in the electrical/battery system and how they perform in certain abort scenarios.

“Crew safety is going to drive our decision-making,” he said, adding that the issue was not about the safety of the abort philosophy or capability, but rather about having requisite power levels during an abort. Mr. Kshatriya added that following last fall’s installation of the four RS-25 engines onto the Core Stage, the SLS for Artemis II is at a much greater state of maturity than was Artemis I, with the SRB segments ready for stacking and the iCPS also deep into processing.

With Artemis II thus pushed back to September 2025, Artemis III—which is intended to achieve the first crewed landing on the Moon in more than a half-century—correspondingly moves to no earlier than September 2026, an almost-year-long delay which Mr. Kshatriya described as “still very aggressive” to meet. Even were it not for the Artemis II delay, today’s leaders did not believe that Artemis III could fly any sooner.

“We are letting the hardware talk to us so that crew safety drives our decision-making,” said Catherine Koerner, associate administrator for ESDMD. “We will use the Artemis II flight test and each flight that follows to reduce risk for future Moon missions.”

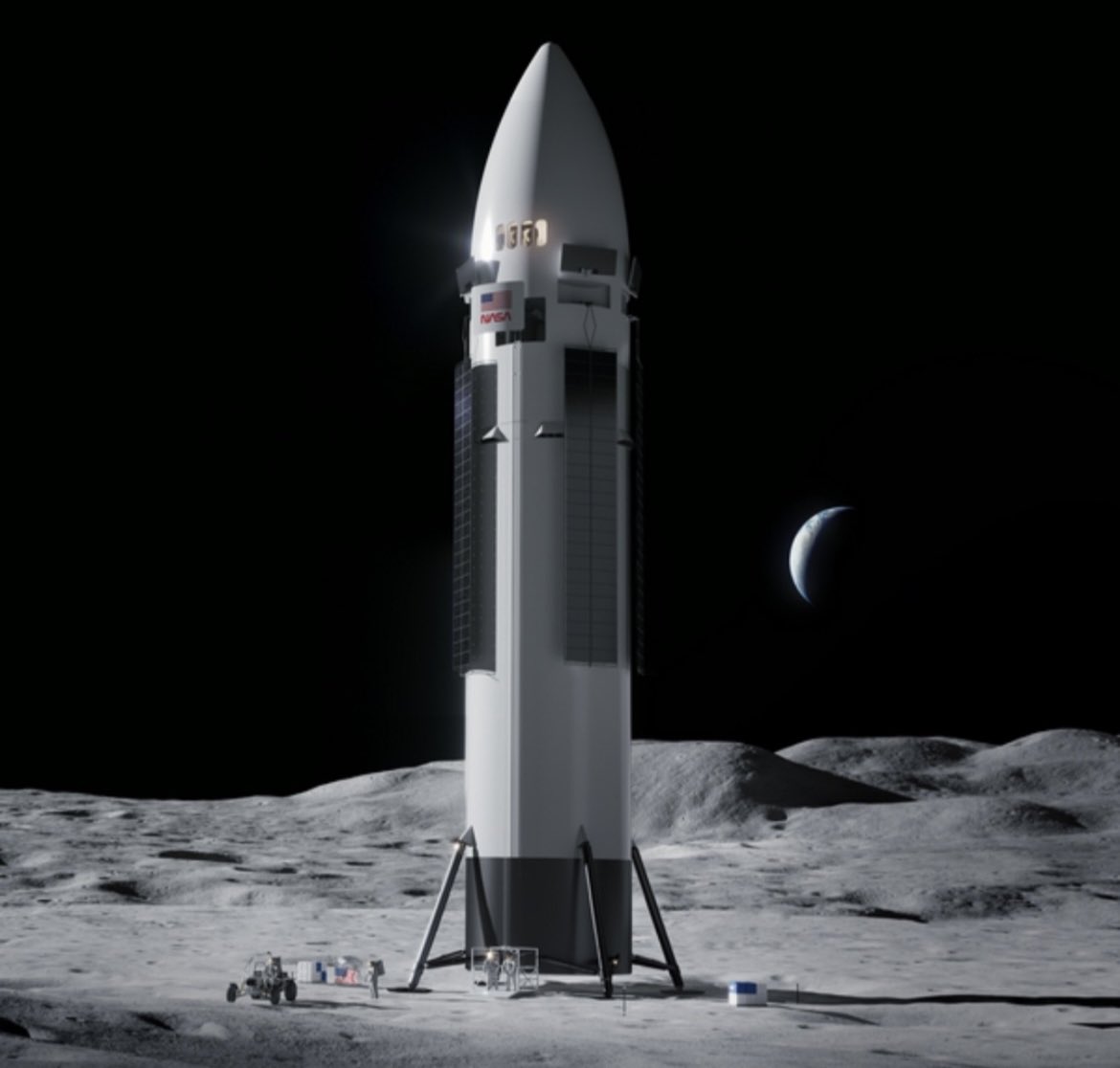

In fact, the development of lunar surface suits, unpressurized rovers, the Gateway, the SLS Block IB and SpaceX’s ongoing attempts to validate its Starship as a standalone vehicle and as a Human Landing System (HLS) require what Koerner describes as “a resilient mission manifest”. Around ten Starships will be required to conduct the “very complex” fueling of the HLS lander, it was revealed, and the dual-launch necessity of ensuring that Orion and the HLS are in the same point in space at the same time to rendezvous, dock and achieve a lunar landing in September 2026 continues to pose a “significant co-ordination challenge”.

“We’ll launch when we’re ready,” acquiesced NASA Associate Administrator Jim Free, noting the multitude of “challenges, both technical and dealing with going back to the Moon”. He insisted that NASA “must be realistic” with regard to Starship, which last April and November conducted a pair of integrated flight tests with some success.

He also pointed out that, despite the delays, there are “no thoughts” of changing the mission objectives of Artemis II or III. Moving into the final years of the decade, the first elements of Gateway—the integrated Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) and Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO)—were previously scheduled to fly in October 2025, but teams will now “review the schedule”.

Here we are re-inventing the wheel, after putting the wheel in storage for 50+ years. Imagine where we’d be if they just continued improving the lunar missions?